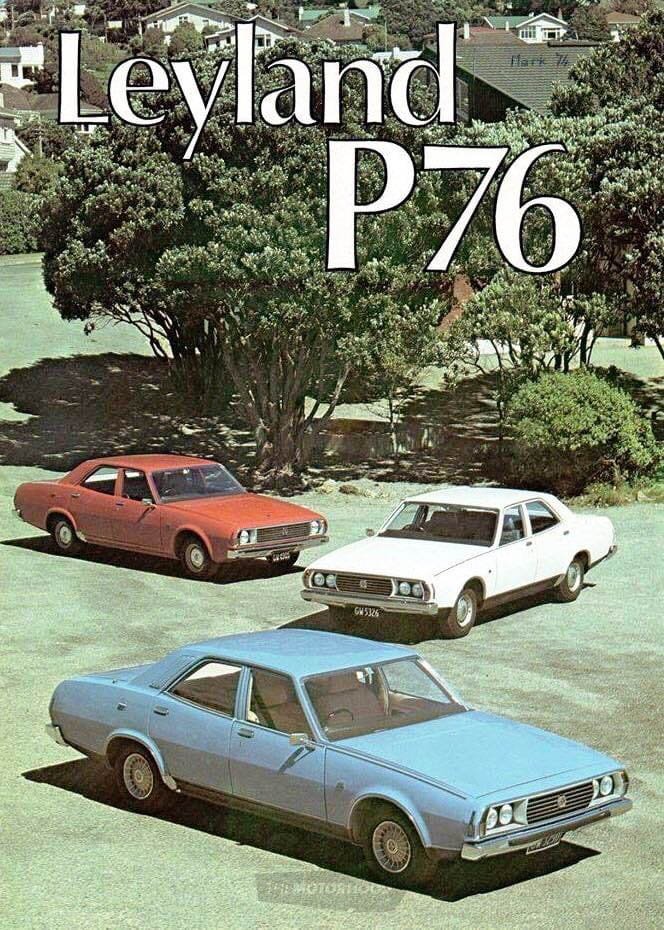

The P76 is another of Leyland’s near misses. When it was introduced in 1973, the Leyland P76 was a genuine threat to the established order over the ditch, having acres of space, brisk performance, good handling, and a swathe of innovations. There’s no way the Aussies were having any of that

By Quinton Taylor

The P76 was ahead in many areas of its Australian ‘big’ car rivals from Holden, Ford, and Chrysler. It was the company’s first attempt at a large car built for Australian conditions. Prototypes even used Holden shells to develop its new running gear. Excellent structural rigidity resulted in a light but very strong body. That intriguing shape was an obstacle for some for sure, but it was bold — as any challenger needs to be — and it makes the car an appreciating classic today.

There was a lot riding on the P76 and, given its positive reception in the press, it deserved to sell better than it did. It was Wheels magazine’s ‘Car of The Year’ in 1973. The sums looked good and it was lighter and handled better than its rivals, scooping them all for superior interior and luggage space.

Demand outstripped supply with more than 2000 cars ordered in its first week of sales, which might have prompted the car to be rushed into production. Dealer servicing and assembly quality control problems arose, which quickly soured the new idea that Leyland could build a reliable car in the Kingswood/Falcon/Valiant mould. More development time could have overcome a number of problems but, as with many Leyland designs, owners have rectified annoyances like vibrating door lock buttons and flyaway window trim, so at least they can enjoy the car’s full potential.

Leyland was actually ahead of the impending new Australian Design Rules with the P76, offering a number of new design features. These included flush, bonded windscreens which quickly became an industry standard, aiding body strength. It had full flow-through ventilation exhausting through C-pillar vents, meaning it did not need quarter lights, and it had airbags and cool concealed wipers.

It had a second firewall for passenger cell and torsional strength, and noise isolation. It was the first full-size car in Australia with rack and pinion steering, and modern four-link rear suspension. It had large ventilated discs, when its rivals had solid discs or even drums, and radial tyres when most other new cars still had cross-plies. What’s more, its four-speed manual, light weight and tall final drive made for unusually frugal cruising. It’s fair to say both Ford and Holden considered the P76 to be a serious threat to their sales.

Driving a wedge

It might have had controversial styling that looked unfinished to some, but its ground-breaking wedge-shaped styling at least delivered a humongous boot that would reputedly take a 44-gallon drum, which some viewed as a major plus, given the rapidly rising fuel prices at the time.

The design is usually accredited to Michelotti but Gavin Farmer’s book, Leyland P76 — anything but average, gives us a different version. Farmer’s British sources confirmed that much of the development work for the P76 was done in the UK at Abingdon. The Sydney plant had no experience or facilities for laying down a large body structure. Rover was also developing a new P8 in almost identical dimensions and, despite being finished way before the P76, Leyland dropped the project. It was close to what Australians wanted in size, with clip-on panels as per the Rover P6 and Citroen DS19.

Leyland Australia’s in-house stylist, Romand Rodberg, knew exactly what his Australian managers wanted and in 1969 he produced his design. He favoured the fresh lines of the new NSU Ro80 as the way forward.

Michelotti’s name was attached after he was given the job of tidying up Rodberg’s concepts in a very short time frame. Allegedly, it was just a week before the final tooling model was locked in at Pressed Steel in the UK. The entire process was undertaken without Australian management seeing the result. Only when it reached Australia did the mismatch between the front and rear tracks, resulting from using local components, become obvious. The tracks could not be easily modified and, unhappily, Leyland Australia decided it had no choice but to put the car into production as it was.

Rodberg had left Australia by the time of the launch of the P76. Both front and rear styling was supposed to have been sorted closer to release, but Michelotti was severely time constrained and local efforts did little to rectify the design. You can’t deny it’s distinctive.

Significantly, Leyland made little mention of Rodberg’s involvement and used Michelotti’s reputation as a publicity boost, though just how happy Michelotti was about that is less clear.

As well as having sharp handling, the V8 version delivered genuine 160kph-plus performance using Rover’s all-alloy engine bored out to 4.4 litres for the P76. It was the first all-alloy engine offered in an Australian-built car and it was a lively performer, with reasonably quiet noise levels at speed. It also added little weight over its 2.6-litre sibling. It was developed from the 2.2-litre six lifted in Leyland’s Kimberly model, which was turned through 90 degrees, mounted north-south in the P76, and increased to 2.6 litres.

A few six-cylinder models came to New Zealand built up, but the models assembled at Petone were all V8s. The big V8 proved economical too, with Grant Howard and Ron Crabtree returning 9.9l/100km (28.4mpg) in the 1975 Mobil Economy Run, beating the Ford Falcon, Holden Statesman, and Chrysler Valiant.

Leyland Australia intended to eventually extend the V8 to 5 litres, along with a proposed V6 of 3,300cc — a cut-down version of the V8, sharing tooling and giving the company a range of engines from 1,500cc to 5 litres. In New Zealand, although it didn’t appear as a black and white liveried traffic patrol car, the Ministry of Transport used a few ‘mufti’ P76 V8 models, and it was well-liked for its performance and handling, and it had few reliability issues.

No room at the top

A key factor in the scope of the P76 that also contributed to its downfall was the high local content levels. Cost-saving measures involved a reliance on rival manufacturers’ components, such as the rear differential shared with Holden models. Component suppliers were loath to upset lucrative contracts with the likes of Ford, Holden, and Chrysler, so Leyland had to wait in line at a time of unprecedented industrial unrest in Australia, creating further shortages. No doubt the three local rivals were less than helpful to the British upstart as they noted a growing list of positive attributes. Leyland’s ability to reach 90 percent local content, beating local hero Holden, would not have gone down well.

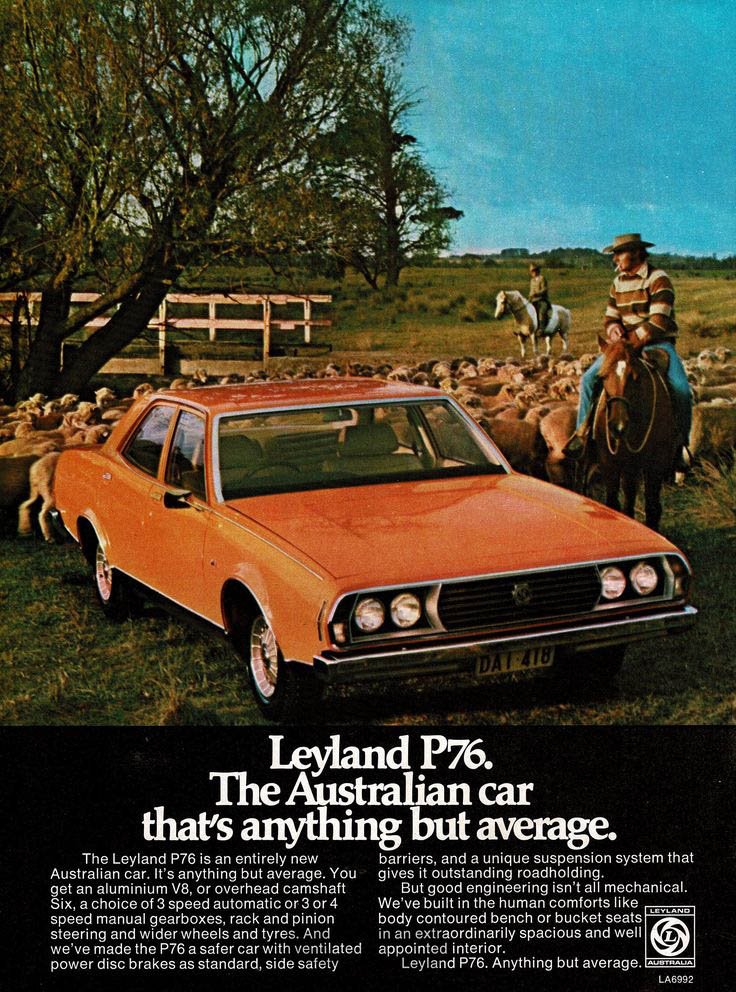

Leyland’s colour range was also cheekily assertive, with names such as Home on The Orange, Am Eye Blue, Bold As Brass, Peel Me A Grape, Hairy Lime, Bitter Apricot, and Plum Loco, adding to the P76’s fresh charm. Interiors were also above average with a range of four interior colours, including a dark brown leather trim, the mid-ranger ‘Super’ version proving to be the best seller.

The oil crisis provided a double whammy for the new car, contributing to an AU$30m loss for 1973. Leyland Australia took it on the chin and went ahead with plans for upgraded models and a station-wagon version. The real eye-catcher, though, was its two-door hatchback sports coupé, the Force 7. There was a well-equipped base model six-cylinder version too, but it was the 4.4-litre V8 version that impressed with a four-speed, floor change transmission, alloy wheels, and an optional performance package aimed straight at Chrysler’s Charger and Holden’s Monaro. There was also an up-market cruiser version, the Tour de Force, with a luxury interior. The motoring press went ga-ga over the coupé.

It was big news but the project was already moribund. It was expensive to produce, sharing few body components with the P76 sedans. Ultimately around 60 coupés were made but many were destroyed. Just 10 were sent to auction, while one was sent to Leyland UK for testing. Apparently Leyland boss Lord Stokes liked it enough to use as his daily driver. This blue with a white stripe car is now in New Zealand.

Towards the end of production in 1975, a run of 800 special edition automatic P76 sedans was built and badged ‘Targa Florio’, commemorating a standard P76’s stage win at the 1974 World Cup Rally. Usually painted in a subtle light blue metallic or green with silver striping, they came with a limited slip differential and power steering as standard. One example in the South Island has recently been restored.

In 1975 Leyland P76-mounted David Oxton and Garry Pedersen were hoping to break the domination of the Chrysler Chargers in the Benson & Hedges series but a broken exhaust stub at Pukekohe saw them pit for a number of laps for repairs. They finished in fifth, having shown the P76 could match the Charger for straight line speed, but with better braking and handling. A second P76 driven by Dauntsey Teagle and Jim Murdoch ran without incident. Oxton and Pedersen were back the following year but the car suffered fuel feed problems and finished well down.

Geoff Ogilvie campaigned a Targa Florio P76 in the 1999 Targa Rally of New Zealand and, as recently as 2019, a 1974 model P76 won the Peking to Paris Challenge, over 8,500mls (13,679km), driven by Matt Bryson and 87-year-old Gerry Crown, again showing the car was fundamentally pretty tough.

But in 1976 the lack of sales was unarguable and the company cried ‘enough’ and canned all P76 production.

Spanish olive

Southland engineer Roy Clearwater has a varied collection in his shed. A Chrysler enthusiast from way back, he has a pristine Valiant Pacer receiving its finishing touches, alongside an immaculate Chrysler Hardtop, one year older but in a similar colour to the car we featured in New Zealand Classic Car in December. Filling out the shed is a collection of Morris Coopers.

His P76 is parked in the driveway, glinting in all its ‘Spanish Olive’ glory, one of five greens Leyland used in the period. The period colour suits the car in its country location. A few tasty ’70s add-ons complement a bling-free body. A 1974 ‘Super’ model, Roy has been able to account for a fair portion of its history, as he explains.

“I’ve owned it for about four years. I think it’s had roughly about four owners before me. Unfortunately, I don’t have the ownership papers but we have managed to trace the last two owners who had long stints with it way back into the late ’70s.

“It’s been a Southland car all its life. I bought it from a deceased estate at Winton and he owned it from either the late ’80s or early ’90s. I think another family from around the Opio area had it for a good decade or so. I got it re-sprayed by Paul Herron Automotive Painters up in Gore, and I’ve had the trans rebuilt to fix an oil leak. I had to do that as soon as I bought the car, and the steering rack was fixed.

“Other than that and fitting the Hot Wires, that was it. Then there were the louvres. That was an absolute mission! I decided the car just had to have louvres or it would have been just a green slug otherwise. Do you think I could find them? Anyone who had them obviously wouldn’t sell them. Long story short, I imported a set from Aussie, then it took a long, long time to find someone over there to effectively build a coffin for them. It was a pretty serious parcel when it turned up. I was really stoked to get those and the postage cost about four times the cost of the louvres, but they really finish it off.”

Roy enjoys the P76’s famous and obvious cavernous boot. He flings the boot lid open to reveal a pristine 44-gallon oil drum to prove the old adage was true. He has done almost nothing to the motor, apart from freeing an occasionally sticking hydraulic tappet. It appears to use little oil. During his ownership he thinks he may have only completed about 1600kms but as he is restoring a number of cars, he doesn’t find a lot of time to drive the P76.

“It’s really, really good to drive. Compared to some of the other classics I’ve got, it just sticks to the road and it handles way better than them and was ahead of its time, really.” Despite the P76’s reputation of being poorly screwed together, Roy has found the opposite.

“The boot lid fit is average but the doors all fit well and, as far as their reputation of being poorly assembled goes, I haven’t really experienced that on this particular car. Overall, assembly is pretty good. Whether that is because the previous owners have worked through the issues and resolved them, or whether I just got a good one, I’m not too sure.”

Roy summed up the P76’s appeal to the modern classic enthusiast. “I think it’s certainly unique and it’s got character. It certainly gets attention one way or another. Everyone’s got a story to tell about them. It had very little rust when I got it painted, except for a little bit by the back window which turned out to be nothing.”

New Zealand P76 Owners Club publicity officer Rob Jones informed us that in the hands of previous owners, Russell and Joy Keen from Winton, it won the People’s Choice Award at the club’s national rally in Invercargill in 2014. Rob says the club is in rude health, with a steady membership spread around the country. A number of P76’s are now under restoration. “There are a surprising number of these cars being restored here and in Australia. We are always on the lookout for cars to restore and they just keep turning up.”

A little slice … ? No, a giant wodge of Australian automotive innovation, with plenty of sensible yet quirky appeal.

This article originally appeared in NZCC issue No. 376