Is this the ultimate Porsche 911? Porsche has made a virtue of keeping the 911 true to its origins, with a policy of evolution, not revolution. It came closest to breaking the mould with the wild whale-tailed 930 Turbo, which catapulted the car into supercar territory

By Ian Parkes, photography High Art Photography

We were stopped at the side of the road, setting up the next photograph, when a faded Toyota slowed alongside and stopped. The window was already down, to give the driver a good look. “That’s my dream car,” he said — speaking for more than a few of us. He drank in the gleaming red paint, shining in the sun, and the car’s purposeful swoops and curves. He exhaled half a lungful of cigarette smoke, gave a hang 10–style thumbs up and drove off.

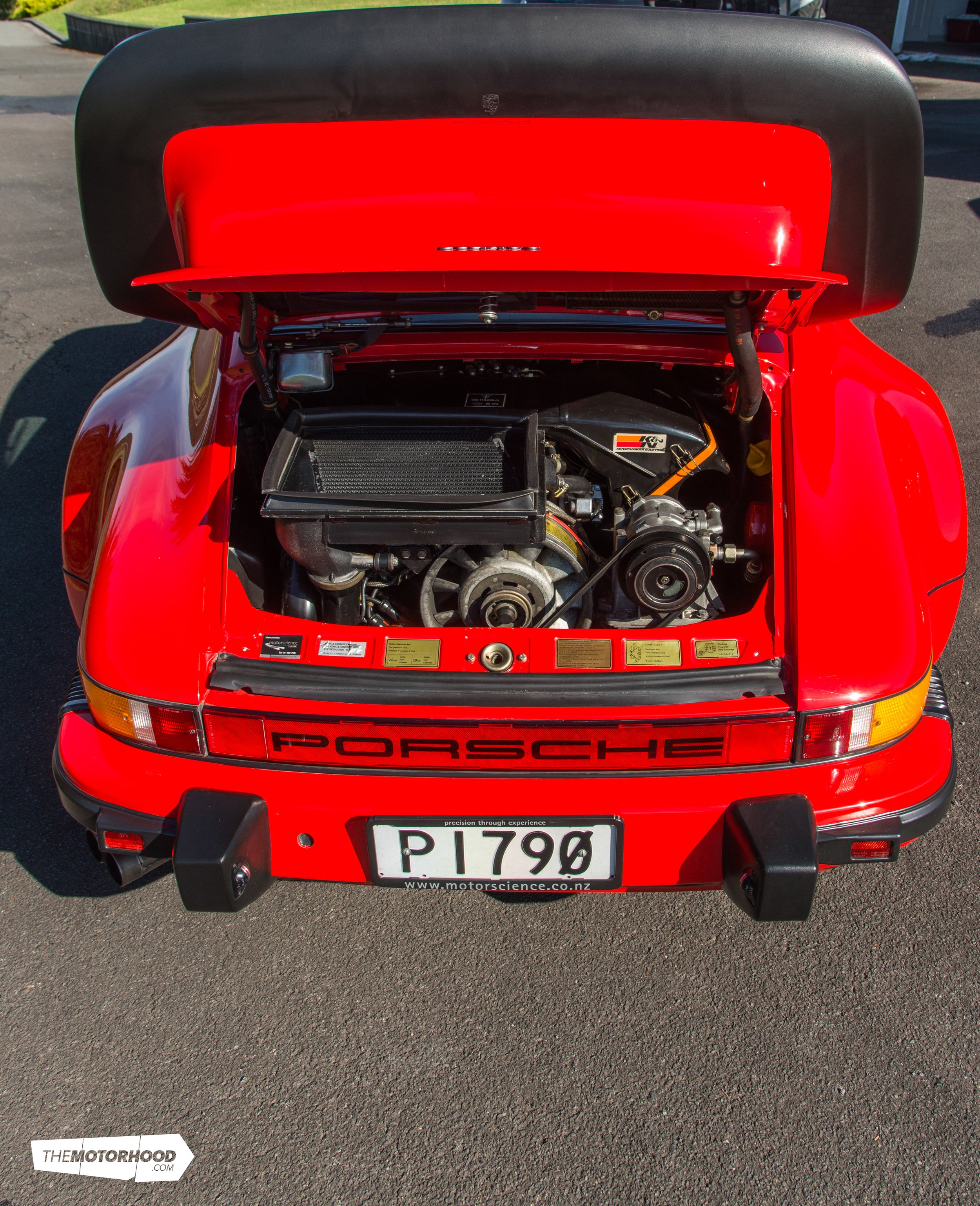

On the side of the road, against a clear blue background, the Porsche stood out in all its stark red glory. It’s the classic 911 shape on steroids. It has the fat, even pouty, front lip of the G series 911s, added to comply with 5mph bumper restrictions in the US. It also has the oversized haunches to accommodate the wider rear wheels and tyres — a first for Porsche, which also confirmed its supercar credentials — and, most noticeable of all, that enormous whale-tail spoiler.

They made it look as if Porsche had abandoned its restrained elegance and handed its crayons to a class of cartoon hot rod–obsessed schoolboys. Looking back, it seems several car makers did the same thing — adding wild spoilers to road-going cars to emphasise their racing cred — but it was over a decade before we got the not-quite-as-wild Sierra Cosworth wing. Porsche’s wing was modified and made even larger in 1977, when it was dubbed the tea tray.

Owner Dick Fisher is used to the attention this car gets. He understands completely. Having built a couple of successful businesses in engineering and building supplies, he has owned, and often still owns, a number of nice cars, including another, later Porsche, a 997, but this car has a special appeal.

Dick owned a Porsche 928 for a while. Having sold it, he realised he really should get another one. He also had to agree with the thousands of 911 fans who eventually persuaded Porsche that the V8 front-wheel drive 928 was not the ultimate Porsche and it should not replace the 911. Like so many others, Dick decided the 930 Turbo probably was the ultimate Porsche. It’s not for everyone.

Despite the leather and electrics, it misses the mark as a luxury car by being just too raw — not surprising when it was originally envisaged as a stripped-out race car for the road, as Porsche had done before with the 1973 Carrera 2.7 RS. It was literally the basis for a racing car, where form follows function. Naturally, fans of the sport and speed and performance would want one for the road.

It’s unclear why Porsche changed its mind — maybe some market research showed the strength of demand — but happily for the company and us, it decided to make it a full-blown road car with all of the usual, for the time, creature comforts. Tellingly, these didn’t include much in the way of electronic driving aids. It didn’t even get ABS; that wasn’t fitted to a 911 — although the 928 had it — until the 964 version was launched in 1989.

Porsche’s First Supercar

However, for many, those distinctive excesses so evocative of the car’s powerful new punch — and its exotic handling, which quickly earned it the nickname ‘The Widowmaker’ — are exactly what makes it so special. It also put Porsche into the same performance league as the great Italian marques, and earned a spot on the wall among the posters of the other great supercars of the era.

Before the 930, Porsche had built a keen following for its 911 but could never seem to satisfy customers’ demand for more power. It lifted the engine’s power from two litres and 130hp at the 911’s launch in 1963 through to 160hp in 1966, to 2.2 litres in 1969, and 2.4 litres in 1971, which gave it 190hp.

Shortly after the G-series, or second generation, 911s were introduced in 1973, the standard engine was a 2.7 producing 110kW (147bhp). The S model produced 129kW (173bhp). The history is complicated by US models getting lower-powered engines — for example, the S was sold as a Carrera, and its power output in the US actually went down in 1975.

The most potent version — which many consider the best-ever Porsche — the Carrera 2.7 RS put out 210hp (154kW) but it was sold as a strippedout race car for the road. It got another 20hp as a three-litre, the Carrera 3.0 RS, with fuel injection in 1974.

Porsche was already using turbos in its race cars but the road-going Turbo as we know it still might not have happened if the FIA hadn’t changed the rules, requiring manufacturers to homologate race cars for Groups 4 and 5 by building at least 400 of them as production models.

Porsche could have made another lightweight Carrera RS version but it made a standard production model and wound up selling more than 20,000 Turbos over a production run of 14 years from 1975 to 1989, which I argue makes it the best ‘production’ Porsche.

The 911 Turbo, to give it its official name, was launched in 1975. The internal 930 designation, which is now widely used everywhere, signified it was a different version of the G-series 911 because it was so much more than just a 911 with a KKK turbo.

Alongside its European track cars, Porsche had already been developing twin turbo versions of the flat-12 air-cooled engines — essentially two flat-sixes — for the Can-Am versions of its 917. That car ended McLaren’s five-year domination of the sport and, as new rules restructuring fuel consumption for safety reasons ended its run in 1974, the 5.374-litre engine in the 917/30, which produced around 1100 horsepower, made it the most powerful sports car ever raced in an FIA series.

Taming Turbo Lag

One of the 930’s most distinctive features is the dramatic character of its turbo lag, which kicks in like a mule after an appreciable wait. Yet, according to one source, it apparently could have been much worse, had the race team’s Roger Penske, George Falmer, and Mark Donohue not worked so hard to tame it in the 917. Engineer and company chairman Dr Ernst Fuhrmann is credited with the creation of the 930’s engine, adapting the turbo knowledge from the 917 programme to the new road car that would underpin Porsche’s new Groups 4 and 5 race car. It was launched as a three-litre, producing 256hp (191kW) at 5500rpm and 243ft·lb (329Nm) of torque at 4000rpm. That was significantly more power than the RS; it was cheaper, too, and better equipped.

The prototype had proven too powerful for the standard chassis so the rear track and tyres were widened, the suspension was revised and stiffened, and larger brakes and a stronger gearbox were fitted. The unmissable whale-tail spoiler was added to help keep the rear end stuck down — but the car’s short wheelbase and the pendulum effect of the flat-six slung mostly behind the rear wheels would not be denied.

It’s easy enough to see how inexperienced drivers — and most of them would have been, as this kind of horsepower was rare back then — were caught out by the engine’s civilised behaviour below 3000 revs, and the turbo lag. An over-confident prod at the pedal, seeking a bit more oomph coming out of a corner, would suddenly unleash wild oversteer, flinging the car rear-end first off the black top, sometimes with serious consequences. For those who knew how to handle the power and who had got used to its quirky delivery, the raw and visceral performance was as addictive as hell.

In time-honoured tradition, some customers wanted even more, so in 1977 the 930 got a 3.3-litre with an intercooler engine delivering 296hp. That demanded the new, bigger tea-tray spoiler. It also got more suspension tweaks — designed to rein in its most excessive behaviour and compensate for the increased weight of the engine — better brakes, new antiroll bars, stiffer shocks, and larger rear torsion bars. It was, apparently, safer but hardly tamed. If you still wanted more, the WLS version added a fourway exhaust system, another oil cooler, a modified front spoiler, and engine tweaks that delivered 325hp.

The car’s persistent uncivilised behaviour perhaps didn’t please Dr Fuhrmann. When the car failed to meet new American and Japanese emissions rules it was withdrawn from those markets in 1980, and, as the doctor continued to back the 928 as the future of Porsche, further development on the 930 was stifled until after he left the company. It was 1985 before an engine throttled back to 282hp went through the certification required for re-entry to the US market.

Jekyll and Hyde

As we dawdle down the drive and wend our way through the town, heading out to the photo location, it is noticeable how thoroughly well made the Porsche is. We had just stepped out of an E-type Jaguar, which was a very good example of its type — it wasn’t the one featured in the last issue but another beautifully preserved Series 1 FHC — but its engine needed a bit of nursing while it warmed up, there was the odd squeak and rattle, road noise, and wind noise as an accompaniment to the silky rumble of its straight-six engine. It was very much a car of the ’60s, with masses of the rewarding character that people pay an awful lot to experience. The unparalleled view down the bonnet of the E-type is a treat on its own.

The Porsche is an entirely different kettle of fish. Shutting the door makes the most satisfying of clunks. It’s immediately apparent there’s not a hint of any sag in the hinges. That’s as you would expect in a car that has done just 54,000 kays — but you feel sure it would not have been permitted in the design. The only squeak is from the leather as we settle in for the drive. It is not in E-type territory but the view through the screen is framed by the classic Porsche front wing headlamp binnacles. Nice. Impressed by the tangible tautness, I remark on the build quality. It is something we have all been conditioned to expect in a Porsche but Dick is sanguine. “It’s had 10 years of development over the E-type,” he says. Fair point.

Looking around the all-black interior, it’s not very special. As noted earlier, this was not a luxury car in the traditional sense. The designers of today’s Porsches pay much more attention to finer points of look and feel of the materials, multifunctional displays, and the ambience in the cabin, to the point of allowing the driver to select how much of the exhaust sound is piped into the cabin. Porsches of the ’70s and ’80s were still very much sports cars. The interiors had everything you would want — fancy things like multi-speed wipers, electric windows and seats — but you get the impression the focus was elsewhere: on the dynamics of the car. The dash has an elegant sweep but the hardware is made entirely of uncompromising plastic. No pointless wood trim here. Once they had made it robust enough to avoid warping and to hold everything in place, the engineers moved on.

Sensational

The absence of geegaws allows you to focus instead on the sounds and the sensations. For all of its fearsome reputation, it is very civilised around town — much more like modern cars — which is the big difference between this and the E-type. The suspension, while firm when rolling over the usual haphazard changes in seal, is close to modern levels. In fact, Dick says that car’s similar to the 997 when it is set to the softest of three settings — at least below 100kph.

The second biggest giveaway that this is a serious sports car, and one from a previous era, is its small size. The windscreen is quite upright and quite close. The seats are close together. The ride height is low, certainly in comparison with SUVs, but I know where I’d rather be. The most rewarding part of simply riding around is the sound of the flatsix engine breathing in its distinctive dry husky way just inches behind you. Pleasingly, it’s a little bit louder than you’d expect.

We get out onto the open road, Dick changes down, the engine shouts, and we fire forward at the narrowing horizon. Like many a Porsche 930 occupant before me, I was taken by surprise. I was pressed back in the seat by genuine old-school acceleration. Warp drive is released as we close in on traffic, and everything becomes calm again. We don’t have the space on the roads today to test the Porsche’s grip on the twisty bits but, on the odd occasion where we can spin up, the turbo is — I hesitate to use this much-overused word these days — genuinely exciting.

Dick confirms the Jekyll and Hyde impression. At 120kph it really comes alive. It’s quite a different car. “The turbo comes in at about 3000rpm and really takes hold and away it goes,” he says. “Probably on a good road it really settles down and it would be a great car at about 140. That’s what it’s meant for.”

It would be easy to imagine both car and driver travelling perfectly happy in the outside lane on the autobahns, lights on, at speeds well above that. We suggested earlier that Dick chose the 930 specifically as the one to own from decades of 911s. He would agree that’s true. When the G series was replaced with the 964, Porsche had started to soften the lines.

“They started to change the shape a little bit, which spoiled it,” says Dick. However, he has owned the car for more than 30 years; it’s actually very easy for him to remember exactly why he chose that model. It was simply the latest and greatest at the time.

“I’d read a lot about them. At the time the 930 was the car. Back then it was at the top end of performance cars. I don’t think there were too many other cars that performed like that. But I’ve always treated it with respect.” Dick bought the car from a dealer who was selling it after the first owner had brought it in as a ‘tourist delivery’ model. He had picked it up from the factory and presumably toured Europe in it before bringing it back to New Zealand.

“It was only a couple of years old, at the most,” says Dick. “I’ve kept it exactly as it was. It’s never been pranged. It’s pretty original. There’s probably not that many now in New Zealand, certainly not in this condition.” Dick is the man who has put most of the 50,000km on it. When he has another Porsche in the garage and a fast saloon car, I asked him what it was that would prompt him to choose to take the 930 for a run. “It has to be a nice day — it only comes out on a fine day — but mostly just to give it a run, to charge the battery up.”

He does have a special fondness for the bright red Porsche, though. “It’s the only car I’ve bought that’s gone up in value,” he says, “and it will keep doing so, but I’ve got no intention of selling it, ever.” There are probably many people out there who look at Porsche 930s as appreciating assets but there are certainly many more like Dick who will hang onto them, just because we will never see their like again.

This article originally appeared in NZCC issue No. 380