data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 169”

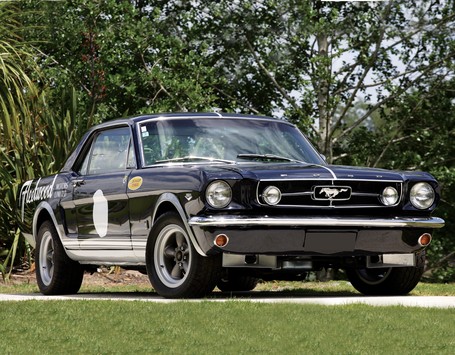

Ivan Segedin and Red Dawson’s Tale of the Fleetwood Motors’ Mustang

Winter 1965, in the depths of rural Waikato, an extraordinary event has occurred — a young farmer has imported a rare and highly prized icon of American automotive culture. Navigating the minefield of restrictive legislation, he has miraculously acquired a high performance example of the classic ’60s yankee youth, dream machine — a state-of-the-art Mustang GT. Racing driver Ivan Segedin had intentions for this beast far beyond cruising Hamilton’s main road drag-strip on Friday and Saturday nights.

The Ford Mustang unleashed its charm on the American market in mid ’64. The combination of sports coupe and personal car captivated the youthful car market and was selling by the truckload. Acquiring one in New Zealand though, was virtually a script from that old TV show Mission Impossible and the Segedin ‘pony car’ was probably one of the first Mustangs to hit these shores.

Ivan had been racing a very quick Anglia over the previous two seasons. He was no mean steerer, tangling with the likes of Jack Nazer (Anglia), Paul Fahey (Lotus Cortina) and the pre-war V8 coupes of Red Dawson, Johnny Riley, Rod Coppins and others. Ivan’s Anglia had been at the pointy end of early ’60s saloon racing technology, courtesy of mate Dennis Simmons’ all-round engineering skills. Fitted with hand-shaped alloy doors, boot and bonnet, it also sported an almost unheard of big-bore 1800cc demon engine with all the tricky bits.

Ivan had enjoyed some great scraps with the other leading cohorts on the North Island circuit, but he had a hankering to run something more exotic. Possibly, this came about from growing up surrounded by the new Ford V8s his father acquired as a sideline to his agricultural trucking business. New Twin Spinner’s and Customlines were pretty tempting fare to a young lad growing up out in the sticks in mid ’50s New Zealand. An earlier racecar had been a larger Mk2 Zephyr with Raymond Mays head that Ivan cut his racing teeth on at Hamilton Car Club encounters.

A Ford man through and through, the latest opposition-crushing device had to have the oval badge. A trip to Sandown Park (Melbourne) in November ’64 to compete in the international six-hour saloon car event almost saw the Mustang never happen. Racing a Volvo with local car dealing tycoon, Colin Giltrap, they finished fifth. Ivan, however, was blown away by the performance of the Holman-Moody Ford Galaxie. With awesome big-block V8 power, Lex Davison and Sir Gawaine Baillie led the field effortlessly until the old bogey of the brakes collapsing, sent the mammoth car through fence and railway sleepers at Peter’s Corner.

Negotiations to buy the Galaxie became protracted. Ivan an addict of the latest car literature, latched on to those motoring prophets who were proclaiming the new Mustang to be a hot racecar. He had to have one of these.

Fleetwood Motors

An arrangement was reached with Bruce Mundy, the manager of Fleetwood Motors in Hamilton (the business was actually owned by Tony Shelly of Wellington and, in later years, Colin Giltrap was the sales manager at Fleetwood Motors), who was making a trip Stateside. Fleetwood’s was directly adjacent Dennis Simmons panel shop, the mastermind of the project and a gifted panel-beater who raced a Zephyr Mk1. Ivan and Dennis specified the ingredients required on the shopping excursion.

A number of myths have been perpetuated over the years, around the running of this car and it’s heritage. For the record, Ivan financed everything relating to the purchase and running costs of racing the Mustang. Fleetwood Motors had no financial interest, nor did it provide any real sponsorship. The car carried their banner on the rear flanks, largely as a goodwill gesture for Bruce’s time spent in the USA teeing-up the original deal. The critical serious money to pay for the import bond was put up by BP, Ivan recalled: “I couldn’t get an import license for it, so the only option was to appeal to a large company to stand the bond.”

This was a lot of money and reflected the unbelievably dictatorial constrictions imposed by the government of the day. This farcical situation required the car to be re-exported out of the country again at time of sale as the bond could only be recovered at the wharf of another country. BP also paid some starting money and provided fuel, etc, but Ivan carried the brunt of preparation costs. At that time, Ivan owned the Motordrome, Atlantic 24-hour service station on Te Rapa straight in Hamilton. Contrary to popular belief, this Mustang GT was not a Shelby, such as the later Fahey and Dawson cars that were, in effect, factory prepared racers.

The 1965-and-a-half Mustang GT, identified with extra fog lights inside the grille, was purchased from the Ford factory. It was one of the limited edition K Code Mustangs (2800 built), which in standard tune offered an output of 271bhp at 6000rpm from its 289ci V8. The crucial part of Bruce Mundy’s US escapade was a visit to the nerve centre of the Shelby organisation in California. The go-faster bits for the unfair advantage included camshafts, a ‘Moon’ manifold, 48mm IDA Weber carburettors, a genuine Cobra alloy sump and a Detroit Locker differential.

Contrary to popular belief, this Mustang GT was not a Shelby, such as the later Fahey and Dawson cars that were, in effect, factory prepared racers

The engine mods increased engine output to approximately 350bhp. Fellow Hamiltonian racing driver and mate, Howden Ganley, at that time in England, arranged for an aluminium T10 four-speed gearbox to be shipped to New Zealand. Over-ride traction bars were bolted through the floor, while 15-inch American racing wheels mated to Dunlop rubber completed the specification list.

Dennis also lowered the front of the car in an attempt to make it handle, and then raised the wheel arches on inch to disguise this modification (as lowering was banned).

Interior-wise, the cabin looked totally stock, with original bucket seats, no roll bars, a standard factory dash with strip speedometer and factory steering wheel. Every second seat spring was removed, brackets were binned, and sound deadening removed to lighten the car, but keep the ‘stock’ upholstery which was called for the current rules.

Laughing, Ivan said that at least the Mustang came with full seat belts — which was almost unheard of at the time. Dennis Simmons, the man for all seasons, lashed all the ingredients together. They were just in time for the Shelby modified Mustang to make it’s debut at the Wills saloon car meeting at Pukekohe in October 1965.

On the circuit

With hardly any testing prior to the debut, a few bugs emerged during practice. A mysterious lack of power saw the Mustang only marginally faster than smaller capacity opposition. Also suspension problems, which would always be the car’s weak link, quickly became evident. With a tendency to swing back on its heels, the Mustang wallowed under power with its nose in the air.

The engine problem was diagnosed on the eve of the race: massively retarded ignition timing. Once tweaked, it was a completely different car in the race. “It took off into the distance,” Ivan recalled. With adjustment and tuning, the suspension improved, but it never handled as well as the later Shelby versions.

Barrelling out from the start, the Mustang was a thrilling sight at the Gold Leaf Three-Hour Challenge. Ivan, with Dennis co-driving, made a sensational debut for New Zealand’s first appearance of the legendary racing Mustang. They led comfortably for the first two hours, averaging 72mph and vanquished the field until brake problems reared its ugly head. Ivan remembers: “I think we left the handbrake on or something and the rear brakes caught fire! We still finished; we used some vice grips and cut off the supply of brakes to the rear and just dr

ove with the front discs. Who knows what happened?”

For the 1965-66 saloon championship season, there were two main categories. The All Comers open saloon class, allowed extensive modification to bodywork, engine modification and transplants. This was still the elite class and the most prized goal. The other series, Group 2, was for more production-based cars with some modifications.

Ivan ran the Mustang in Group 2, with occasional forays into the wild hybrid territory. He figured this was his best opportunity, competing with similarly configured machinery until they really had the Mustang humming. This campaign however, was the peak of the Mustang’s racing life, results wise¦ Ivan bit the bullet and took on the complete championship trail down into the deep south. It was a fairly successful mission.

With Group 2 divided into categories up to 1300cc and over, Ivan won four rounds at Renwick (Marlborough), Pukekohe, Levin and Wigram (Christchurch) with a second place at Teretonga (Invercargill) behind Alf Bell’s Cortina GT. The opposition wasn’t exactly ferocious, coming mainly from Ian Bradley’s Lotus Cortina and Bell’s Cortina GT each scoring two wins apiece. This won Ivan the over 1300cc title, but only third place overall behind Jim Mullins and old mate Brian Innes in their 1293cc Mini Coopers. The three retirements during the race series had cost Ivan dearly in the overall stakes.

Unfortunately, he had less success in the torrid, bruising All Comer’s battleground. One point-scoring finish was all the Mustang could manage, with a fourth on the tight and narrow road circuit at Renwick.

Highs and lows

Horsepower was not a problem, but reliability and getting the power to the ground was becoming a growing headache. Weight transfer caused wheel spin and the Mustang’s early spec’ engine was an ongoing saga of problems with the rocker gear. Lack of experience and knowledge with these engines was a sobering and, at times, expensive affair. A dropped valve and a lot of trouble with not enough oil getting up to the rockers, caused the non-threaded pedestals to pull out. This all added grief to Ivan’s self funded budget.

The highlight of the season was his win in the 30-minute saloon race at Wigram. On a damp track with lights blazing, the Mustang looked and sounded magnificent, bellowing around the wide horsepower-favouring track in fine style to a superb win.

The low point was the only reverse direction (anti-clockwise) end of season meeting at Pukekohe in April 1966. A sleeve had been fitted into one cylinder and this apparently dropped with disastrous results. As Ivan put it tactfully: “It was pretty disappointing!”

Interior-wise, the cabin looked totally stock, with original bucket seats, no roll bars, a standard factory dash with strip speedometer and factory steering wheel

A new block was required for the second season and Nick Begovic organised the import of a short block 289ci replacement from Brisbane. This proved to be another arduous encounter, dealing with over officious customs authorities. Flown in, the engine immediately had to be re-exported back out before it could be brought back with spares to defer the usual bond nightmare. Ivan ruefully reflected: “It was incredibly hard to get anything. Just another short block sandwiched in the middle.”

Dennis made some modifications to the Mustang over the winter, fitting a bonnet scoop and raising the rear of the hood to aid cooling. Various exhaust and extractor combinations were tested, including the infamous Rod Coppin’s-style organ pipes through the bonnet (they looked atrocious) in the quest for more power. A wide tray-like exit pipe set up similar to a style used in Australia was trialled, but neither gave any substantial improvement, so they reverted to the original arrangement.

Power output was the name of the game for the 1966-67 season, with the arrival of Paul Fahey’s ’66 Shelby Mustang and Robbie Francevic’s 427ci Galaxie-powered ’55 Customline — the legendary Custaxie. But reliability, or rather lack of it, was at the bottom line and Ivan’s brief second summer of racing was a chapter plagued with rocker and valve train problems, as well as other woes.

A year on from its illustrious debut, Ivan pulled into the pits on lap five of the 1966 Gold Leaf Three-Hour Challenge with a broken rocker stud. After a 14-minute delay, two more laps were managed before it was pushed to the back of the pits.

Ivan’s season slumped even further, when he appeared at the November 1966 Pukekohe national meeting. Qualifying reasonably well for the All Comer’s feature, he was running third behind Nazer (Lotus Twin-Cam Anglia) and Fahey (Shelby Mustang) in the preliminary. Then bang, another internal haemorrhage in the Mustang’s fragile power plant effectively terminated his season. A new engine was the only cure, but Ivan’s resources weren’t looking so flush, so he elected to flag away the Mustang.

Red Dawson

Ivan was dismayed with the engine-breaking Mustang and put it up for sale complete with the damaged mill. Along came Auckland hard man, Red Dawson; a combative no holds barred racer with a legendary in-fighting reputation as long as your arm. A pig farmer turned used car sales operator, Red had begun in the crash and bash jungle of the late ’50s Auckland stock car fraternity before moving to the sealed circuits.

The last couple of seasons he had been racing the ex-Frank Matich 1963 2.5-litre Brabham-Climax, which had mainly been a grim saga of mechanical misfortune with the occasional bright spot, such as a great win in the 1966 Waimate 50. Rumour had it most of the good gear had been removed from the Brabham-Climax prior to his acquisition.

Red was hoping for better things with the blue Mustang and vowed to get on top of the engine maladies that had dogged the car. A new 289ci Cobra mill, with extensive engine mods, was built up over the winter of 1967. This was installed after the usual import shenanigans that saw the machine exported to Sydney where the deal was done and Ivan and BP recouped their loot — then Red re-imported it! The Mustang’s curse for mechanical grief seemed like an irrepressible tide and Red’s season with the beast was blighted by constant breakages, allied to spasmodic, but blinding runs.

Possibly an omen of events to come was his November 1967 debut and retirement from both championship events with the Mustang and Brabham. Against the likes of Fahey (Shelby Mustang), Rod Coppins (ex-Geoghegan Mustang) and Frank Bryan’s new Shelby Mustang, Red’s Championship quest was a total disaster. Four points for a third place at Pukekohe was his only dent in the scoreboard, as compared to eventual champion Fahey’s 56 points, Bryan’s 36 and Coppin’s 34. Red was light years away from the opposition. Only Robbie Francevic’s totally temperamental seven-litre Ford Fairlane fared worse.

To say the whole season was laden with doom would not paint a totally accurate picture. For whatever peculiar reason, Red and the Mustang saved for best two scorching virtuoso displays at non-championship meetings on consecutive days. At Levin on November 25 1967, he took out the Levin Championship 30-minute race from Frank Bryan’s Shelby Mustang in a commanding performance. It was this car of Bryan’s that Red was to purchase for the following season and later win the 1969-70 saloon title in a tie with Rod Coppins.

However, the real highlight of Red’s season came less than 24 hours after his Levin victory. Towing the ‘Stang overnight to Timaru for the South Island track’s opening meeting, he stunned the huge crowd of 10,000. Starting from the back of the grid (no practice), he hurled the big Ford around the twisting circuit in a mind-blowing display of power driving and clinched the feature race.

A year on from its illustrious debut, Ivan pulled into

the pits on lap five of the 1966 Gold Leaf Three-Hour Challenge with a broken rocker stud

In between there were the odd major tragedies, like two engines ventilating themselves at high revs. Flat-out on the back straight at Bay Park (Mt Maunganui), December 3 1967, in third place while chasing Norm Beechey (Chevy Nova) and Fahey, a promising race went sour when the mill scattered itself. Later during Wigram practice sessions in January 1968, the replacement V8 also blew to bits, ending Red’s southern tour in a nanosecond. Yet another engine was procured, or cobbled together, before the end of the season that saw Red record a third place in an incredibly long handicap race of 24 laps at Pukekohe in March 1968.

Racing swansong

There was a scattering of other places picked up here and there, but this was largely the end of the trail for the Mustang. New Zealand’s original racing Mustang had its last racing encounter at Bay Park on July 27 1968, finishing with second and third placings. The largely homegrown Shelby-modified Mustang racer witnessed brief moments of glory. Suspension and engine weaknesses were cruelly exposed following the inaugural season when it was confronted the Shelby-built versions. Red realised this and sold the car at season’s end, replacing it with the Bryan Shelby machine that would make him a folk hero in the ensuing seasons.

With no one wanting to race the old Mustang, Red removed the quick gear and returned it to road car specification. It was sold to Stanley Calcott of Palmerston North with 18,350 miles on the odometer.

Revival

Some 20 years later, Glenn Larsen from Upper Hutt, looking for an early GT to restore, purchased the Mustang. After researching the car’s history to aid the rebuild, he was delighted to discover the car was indeed the original Fleetwood Mustang as raced by Ivan Segedin and Red Dawson.

Taking possession of his new steed, Glenn’s appraisal was that this classic machine looked a tad shabby and rather tacky in light blue with gold stripes. Cheap alloy wheels also didn’t do the car any favours. With the knowledge of its historic origins, a complete rebuild and refurbishment to Shelby specs and Fleetwood colours was undertaken.

Restored to similar configuration, as when it first appeared on racetracks in this country almost 40 years ago, some of the Mustang’s original dodgy traits are still in evidence. A gentle touch on the loud pedal is critical to avoid the back-end breaking away and it is a nightmare in the wet. Larsen described it: “As plagued with extreme traction problems under acceleration”. Some things never change.

The car has appeared on display in the historic Bay Park section of the Te Puke Auto Barn. It fills an important living link with the rich heritage of New Zealand’s motorsport history from the 1960s. Also, it was of course, the first Mustang that was raced in anger on our local racetracks