data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 198”

TVRs and everything about them is as British as you can get but, unlike Ferrari (also celebrating its 60th anniversary this year), TVR could never be considered as an aristocrat of the motoring world, more like the endeavours of a madly enthusiastic bunch of working class heroes from a part of Britain which had little connection with the motor industry. True, Blackpool did indeed represent the start of Jaguar, being the place at which William Lyons, its founder, started making Swallow sidecars (again for the working classes). But the astute Lyons soon realised he needed to be in the heart of the motor industry — Coventry.

Lancashire Hotpot

TVR never built cars for astute reasons, it built them because it was passionate about them and resolutely remained in Blackpool. Blackpool, as well as being a port, is where the British working class went for holidays. Not for the beaches and cold coastal climate, but for the amusement parks, cheap bed-and-breakfasts, bright lights and entertainment. Blackpool doesn’t do sophisticated, but it does know how to give you a wild ride and put a smile on your face.

The TVR story is one of passion and incredible highs of entrepreneurialism mixed with equally depressing lows, in which the realities of industry hit it hard. Its cars have a purposefulness that predisposes them to ultimate beauty. What TVR appealed to more than anything else was the British sense of individuality, and the fact it was a tryer. Originally its vehicles were no more than an alternative to other British sports cars, using the same powertrains in a lighter, more striking body: it was TVR’s rediscovery of the V8 that put it on a plane of its own.

Late model TVRs are fast. More often than not faster than very sophisticated Ferraris, Maseratis, Porsches and conventional muscle cars. A good example in New Zealand is Carl Hansen’s TVR which, despite having a powerplant that started life as a Rover V8 engine, is by some margin the fastest Super GT in at the moment; capable of beating the most sophisticated, turbocharged Porsches. TVRs produce performance in supercar territory from components found from far less exotic cars, put together in a workmanlike fashion with exciting bodywork, but for a fraction of the price of the cars they share performance figures with. Fun for dollar, there isn’t much that beats a TVR.

Backbone

The backbone of TVR success, or more correctly, survival, has been the company’s insistence on simplicity of construction with adaptability to different power units and suspensions. These elements made the TVR a winner. And if the suspension parts originally chosen (from VW) made for hair-raising high-speed handling, as time went on they developed their own system using parts from Triumph and Ford, and finally settled on what was basically a Jaguar rear-end arrangement and a MkIV Cortina front in the Tasmin. Even the latest cars employ bespoke systems that owe their origins to these beginnings. One departure from this was the ‘S’ convertible series, which used a suspension arrangement similar to the Ford Granadas and Sierras of the time.

As you can imagine, working out a logical TVR model progression needs time, expertise and concentration, especially as the Blackpool concern’s history had been so turbulent. Old favourites keep returning, and the company keeps reinventing itself from what seems like certain doom.

Today, however, TVR is going through one of its periodic bad times. It seems hard to imagine that less than 10 years ago TVR was the people’s favourite, and the company was bringing out model after spectacular model, with football stars buying them by the kit-bag load. Production of TVRs in Blackpool stopped last September, 20 cars apparently remain in the Bristol Avenue factory, and whilst arguments rage over the company’s name, products and premises, it’s possible the marque will not actually survive its 60th birthday.

The problems all started when John Ravenscroft, TVR’s resident engine guru became nervous about Rover engine supply. They decided to do their own and Al Melling convinced TVR management he could do it. The AJP (Al, John and Peter) engines would be a considerable achievement for a company that produced only 1200 cars a year.

They did eventually build them, and the Melling V8 engines were clever, light and powerful. They were not, however, cost effective, and didn’t espouse the character for which TVRs had become known. When it was found that Melling’s straight six could produce as much power as his V8, the V8 was dropped. TVRs were loved for their thundering exhaust note — Melling’s flat-plane crank V8 sounded like a four-cylinder. The straight six was equally powerful and light, but it didn’t make the noise that TVRs were admired for. So the company had lumbered itself with immense investment in something customers never asked for.

Vodka Tonic

In 2004 TVR’s then owner, Peter Wheeler, sold out to a 24-year-old Russian whose father, a banker, had been a friend of Boris Yeltsin. The bank went under but, surprisingly, young Nicolai Smolenski was still a multi-millionaire. He had big plans for the marque, including going into leisure boats.

Unfortunately for the Blackpool workers, things turned to custard despite new models like the spectacular Sagaris and T350 coming onto the market. Luckily Mr Smolenski sold the company to an unknown buyer just days before it went into liquidation for about the fifth time in its history. But come sale time, who should turn up to buy the assets? Mr Smolenski.

Perhaps not surprisingly, TVR regularly appeared on the pages of the English tabloids — not for making cars of course, the media are never much interested in that, but because of the antics of its directors.

They even regularly appeared in the business pages of upper crust newspapers when the Department of Trade and Industry smelled a rat. The upshot of all this seems to be that, although the spare parts are all under control and safe in British hands, the manufacturing, if it ever starts again, will be transferred to Europe.

TVR, if it ever returns, will be a brand with its soul ripped out — just like Jaguar and Aston Martin. This has to be seen as a major stumbling block to TVR’s continued existence — what helped TVR survive so many times in the past was its heart and soul.

Crisis management

Although originally founded in 1947 by Trevor Wilkinson, TVR’s most successful phase — the modern era — began in 1982 when Peter Wheeler took over the company from Martin Lilley. Lilley, himself passionate about the marque, took the loyal Blackpool workers through a period of low demand, the oil crisis, a decimating factory fire and crippling strikes by suppliers, but gave the cars and the company a sense of identity and credibility.

During the ’60s and ’70s TVR survived exclusively by making coupes — short, stubby, powerful and proud — using Triumph or Ford running gear. TVRs had their shortcomings, but the one which seemed least forgivable was poor access to the luggage space. Lilley made the TVR practical by giving it a hatchback, and calling it the Taimar.

The Taimar was a success, and in the development shop they saw that once they’d hacked the sloping rear off, the obvious further step was to hack the roof off altogether. What they saw was the blinding flash of inspiration that would open the floodgates of TVR sales. A convertible. Why hadn’t they thought of it before? Who knows — it rains a lot in Blackpool.

TVR actually did quite a lot of work on the convertible before it entered production —it wasn’t simply a roof chop. The scuttle was lowered and the bonnet flattened at the back, the doors had elbow pouches cut into them, and a whole new rear was manufactured featuring TVR’s first ever boot-lid. Mechanically nothing much changed, because TVR’s backbone struct

ure does not depend on a roof for rigidity. The car was fitted with side screens and a folding hood.

It was just what the public wanted — the MGB and Triumph TR were dead, and here was a sports car that looked like a classic and was powered by a lusty V6 engine.

With this first taste of success, the subsequent Tasmin was a risky venture for Martin who realised that TVR’s iconic styling might actually go out of fashion.

Determined to diversify, he ordered a chassis that addressed all the known problems of current TVRs. He planned three new models, a coupe, 2+2 coupe and convertible. Sensibly, TVR did one at a time, each using the tried and tested Ford V6. The coupe came first and it was nothing like any previous TVR, its sharp, wedge-shape penned by ex Jaguar and Lotus stylist, Oliver Winterbottom. Not everyone liked it, but then not every one liked the old TVR. It was a considered success until the convertible came out, and at that point sales really started to look good. The 2+2 didn’t last long, but the Tasmin (named after one of Lilley’s girl friends) became one of TVR’s best-selling cars. would become doubly so when Peter Wheeler widened the chassis by 76mm and added a Rover V8.

It was the start of the TVR revolution.

The Wheeler era

After paying a visit to the Blackpool factory as a TVR customer Peter Wheeler, who had recently sold his chemical company, bought it lock stock and barrel in 1982.

When Lilley handed the reins over to the shy but imaginative Wheeler the new boss undoubtedly captured the hearts of TVR customers and, in short, he found a new market share that made the company, for a while, truly profitable. Wheeler’s TVRs were loud, powerful and, in an era of political correctness, most definitely non-PC.

V8 Power

It all started when Rover’s 142kW (190bhp) all-alloy V8 was dropped into the Tasmin. The 350i convertible quickly became the company’s best-selling model, starting a trend that harked back to the days of the original Griffith. TVR engine outputs got sillier and sillier with the help of ace tuner, Andy Rouse. The 205kW (275bhp) 390SEwas followed by the 239kW (320bhp) SEAC 420, which used a body made of Kevlar, featuring an even more rounded front and a tea tray rear spoiler.

TVRs generally got better-looking when the sharp angles were softened up, but wild spoilers and other add-ons began TVR’s reputation for outrageous styling. TVR buyers seemed to be gagging for the latest, most outrageous specification.

With its high media profile, and having moved away from the bread-and-butter end of the market, it was clear that many people aspired to a TVR but couldn’t afford one. There was also a dearth of ‘classic’ convertibles on the market. Bucking the wild child trend, Peter Wheeler astutely provided a no-nonsense cheap convertible with styling directly linked to the TVRs of old. The entry-level V6 convertible sold like hot cakes and gave the company a steady platform from which to launch many crazy stunts.

The emphasis of this new car was to make it cheap, so it used mainly Ford Sierra running gear with drum rear brakes, had the Tasmin-type Targa top and a totally different screen area. The car was developed through S1, S2 and so on, but really hit the headlines when Wheeler dropped the Rover based V8 in it. That is when enthusiasm for the car went ballistic.

It actually happened by happy accident. The Griffith was planned to be made with the Melling V8, but development of both was protracted so Wheeler decided to fulfil the pent up demand by supplying the old school ‘S’ with an old school Rover V8. Demand outstripped supply. When the Griffith design was ready, the Melling engine still wasn’t right, so the Classic with the Rover V8 was introduced, again to wild acclaim. It was the beginning of the TVR’s diamond years, with the Griffith’s rumbling V8 road car and Tuscan race cars, initially with TVR tuned Rover power, and then the Tuscan race car series used to speed up durability testing of the Melling AJP V8.

The modern Griffith

The race track-only 343kW (460hp) Tuscan was launched in 1989, and the 400 in 1990. The 254kW (340hp) 5.0-litre version, the 500, was launched late 1993. Jeremy Clarkson led a chorus of extremely enthusiastic press comments. The car made as much as he made the car — both possessed similarly outrageous personalities and grew together on a platform that raged against mealy-mouthed greenies.

The TVR Griffith reassured the world about British sports cars and put TVR squarely on the map, and TVR would go on to build some of the world’s fastest and most uncompromising sports cars.

Despite changes to the Griffith engine, the car’s styling remained almost unchanged and a new, slightly less brutal and more user-friendly Chimaera came on stream alongside it — eventually becoming the company’s best-selling model.

it was around this point that the Melling-designed AJP8 was mooted. The AJP8 took much longer than anticipated and, initially, the Chimaera (launched in 1991) was available with the same engine options as the outgoing Griffith, a 4.0-litre 179kW (240bhp) version and a 4.3-litre 209kW (280bhp) Rover engine.

Unlike with the Griffith, however, most buyers opted for the smaller engine. The Cerbera was introduced in 1993 for TVR enthusiasts wanting a closed coupe and rear seats. The Cerbera was significant for being the first model introduced with TVR’s own AJP engine.

Between 2000 and 2002, TVR was making a very healthy profit, its cars were appearing in Hollywood blockbusters and it even entered a works team at Le Mans. Like all successful marques, small industries set making after market enhancements.

What the future holds for TVR is unknown, if the company does indeed disappear, at least we’ll still be able to admire the cars such as those featured in this article.

The Original Griffith

In 1962 Jack Griffith stepped into TVR’s life. Griffith ran an auto repair workshop in the US which, amongst others, prepared cars for racers such as Gerry Sagerman and Mark Donohue — both of whom had driven the works TVR Grantura at Sebring in 1962. According to TVR folklore, one day Griffith was working on Donohue’s Cobra and, just to see if it would fit, he pulled the 4736cc (289ci) Ford V8 out of the Cobra and shoe-horned it into Sagerman’s TVR. The result was a car that significantly outperformed the Cobra.

Griffith contacted TVR, requesting the factory supply him with a slightly modified TVR Grantura chassis minus engine or transmission. It was too good an offer to miss, and TVR was soon supplying chassis at the rate of five to 10 per week. Chassis modifications included beefed-up suspension pick-up points and altered spring damper rates but, in effect, the Grantura chassis was hardly changed from standard — even the MGA/MGB differential was unmodified.

The Griffith 200 was available with up to 202kW (271bhp) on tap. In this last configuration it was claimed the Griffith 200 could despatch the 0-60mph dash in 3.9 seconds before storming on to a maximum speed in excess of 241kph (150mph). It took a brave driver to exploit the outer limits of the Griffith’s handling envelope.

Overheating and poor finish were partially addressed in 1964 with the Griffith 400, with TVR’s new Manx-style tail. By 1965, 310 Griffiths were eventually built, all but 20 being sold in the US, but they didn’t make money.

Lilley reinstated the Griffith name from April 1966 to January 1967, producing 10 cars under his new ownership of TVR, renamed the model the Tuscan V8, establishing a line of cars that would eventually run to the Tasmin-bodied 350i. Under Peter Wheeler, the Griffith name would reappear in 1990 on the Griffith 400, which would eventually evolve into the fire-breathing Griffith 500s we see here.

Gerald Baldwin’s 1988 TVR S1

Gerald was looking for a sports car on the internet

for 18 months. He found this TVR for sale on the Classic Car Fair site, and purchased it from previous owner who was touring the South Island. That was three years ago, and Gerald says TVRs have the sound, style, shape, and individuality of a small-run sports car. With 57,000 miles on clock, it is one of only four S1s in New Zealand.

John and Penny Scott’s 1983 Tasmin 280i Convertible

NZ Classic Car used to do a column called Driving the Ads, the first column written by this author for the magazine. This Tasmin was featured in that column, in which wrote: “Buy this car and convince your friends that you’re absolutely stark staring mad!” At the time, this Tasmin TVR belonged to Compliance Engineer John Friedel. It’s just possible that am responsible for John and Penny owning it. It looks as good now as it did when undertook a road-test of it many years ago.

Martin Johnson’s 1979 TVR 3000S

Martin says, “Previously I had owned an S3 which was stolen and written off. This replaced with an S3C, which had to sell prior to emigrating to New Zealand as Land Transport would not allow me to import it due to the legislation of 2002. It only took me one month of driving on empty New Zealand roads to realise I needed to be driving a TVR here again. A friend back in the UK bought the car for me and shipped it out to New Zealand.”

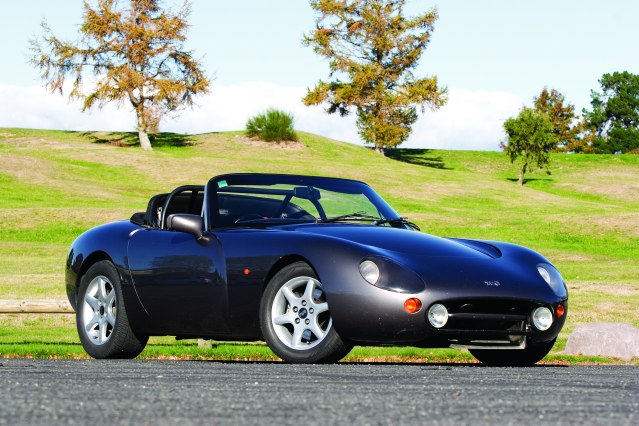

Jim Gamsby’s 1996 TVR Griffith500

Jim has owned has owned around ten TVRs over the last 24 years, ranging from a 1970 Tuscan V6 to this Griffith 500, which he has now owned for two-and-a-half years .

Jim’s first TVR was a ’73 3000M — others include 1600M, 3000M, Taimar hatchback, two 3000S, S2, Kevlar-bodied 420 SEACand Chimaera. Many years ago Jim owned MGBs and a Morgan 4/4, but once he had driven a TVR he was smitten. Jim had his own TVR restoration/repair business in Maidstone, and came to New Zealand 12 years ago.

As he puts it: “TVRs are rare British sports cars with character, they’re quirky and hand-built but put a huge smile on your face when driving. They handle well and sound terrific.”

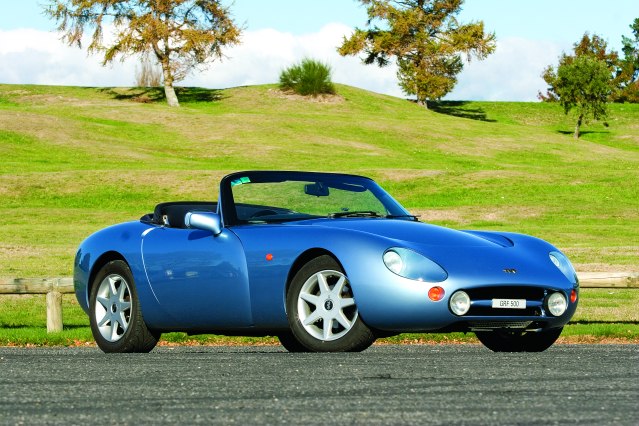

Geoff and Denise Kelly’s 1998 TVR 500 Griffith

Geoff and Denise — “We saw our first Griffith around 1993-’94 and had to have one! We read up all the information we could find, and finally managed to trade a Cobra on our present car in 2000. We actually saw this car brand-new at the Big Boys Toys show in 1998 and weren’t sure about the colour combination, but now we love it. It was ordered new from the UK and was the last brand-new TVR to be imported into New Zealand. It is fitted with sports suspension and a Hydra Trak differential. With its bright yellow paintwork, purple leather interior — complete with yellow stitching — and yellow dials, this Griffith is certainly no shrinking violet!

Leyton Tremain’s 1979 TVR 3000 S

Leyton tells us why. “TVRs are insane and non PC! Enough said! I fell in love the first time saw and heard one (a green Griffith). After riding in Philip Kiess’ Chimaera and experiencing its power and performance, became blind. The more have learned about the marque the more loved the cars. I love their relative unknown status, looks, noise and performance, individuality and the company’s underdog struggle.”

Leyton’s 3000 Sis powered by a 104kW (140bhp) Ford Essex V6. It had side screens, and was the one of the first convertibles ever made by TVR. Production was 258, with 13 turbocharged 3000Smodels.

TVR 60th Anniversary

New Zealand was the first country to celebrate 60 years of TVR, led by enthusiastic club organisers Jim Gamsby and Leyton Tremain. Getting every TVR in NZ together at once was a mission even the passionate Gamsby couldn’t achieve.

Instead, the celebration on the shores of Lake Taupo mustered nine of the British Bulldogs — Jim reckons there are 69 TVRs in New Zealand, 49 of them road registered.

One of the first TVRs ever built is believed to be in Zealand — one of six Atlanta-bodied TVR saloons built in the early ’50s. The story goes that the New Zealand owner brought it along to a Sports Car Club of New Zealand meet years ago, and no one believed it was a TVR, so he disappeared, never to be seen again. If anyone knows the whereabouts of this car we would be very keen to find it and put things to rights.

Unsurprisingly, the cars Jim managed to coral from all corners of New Zealand represent the marque’s best sellers — the Griffith and variations on the ‘S’ theme.

Interestingly, despite being a company that established itself exclusively on short, stubby coupes there were none at the reunion — all were convertibles. According to the TVR club, on the road in New Zealand currently we have: two Vixens; one Tuscan; two 3000Ms; two 3000S; seven Tasmin 280s; three 350is; three S1s, an S2, an S3, and an S4; 13 Griffiths; 11 Chimaeras; one Cerbera and something called a TVR 35-20 (we don’t know what that is!)

There are also many currently unregistered TVRs in New Zealand. Those the club know about include a Grantura 2A that needs restoration; an almost complete Grantura: a Vixen in a shed in Drury; a Tuscan V8 race-car; a partially rebuilt 3000S; a 350i, 390SE, 400SE, S3c, S1, S2 and V8S; two Griffiths, two Chimaera race-cars, three Chimaera road cars (and one written-off Chimaera); one Cerbera (and another being rebuilt); a Tuscan Speed Six and three Tuscan race-cars.

If you know of any more, Jim and Leyton would be happy to hear.

Many of the unregistered cars are quite recent, falling foul of some ridiculous New Zealand legislation which prevents them being registered. Some were registered and complied before the NZ Authorities realised they had slipped through and claimed back the registration plates. One reason to try and get more of these owners to come out of the woodwork is to provide a united front to the LTSA.

NickSullivan’s 1994 TVR Griffith 500

Christchurch-based Nick loves the raw power and noise of his Griffith, which is an early non catalyst-equipped model — its 5-litre V8 punching out 298kW (400bhp). This Griffith is also fitted with five-stud wheels, larger front brakes, an uprated fuel system and a factory roll-cage.

Steven Davies’ 1993 TVR Griffith 500

Stephen saw the yellow Griffith later purchased by Geoff and Denise Kelly at Big Boys Toys in 1998, and still remembers the sounds made by the TVR when its engine was running at the show. Had to have a TVR one day! Stephen’s car is the ex TVR promotional vehicle — TVR always made its promo cars go a little quicker for press demos in the UK, so this one is a real screamer.

Words Tim Nevinson Photos Jared Clark