data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 185”

Penn examines a car hailing from an era when the British made quality cars

David Batterton took off the dust sheets to reveal an exceptionally pretty vintage car. One glance tells you you’re looking at a very original and very genuine little collectable — in fact a wide bodied two-seater 1928 Alvis 12/50 with body by Cross & Ellis, which had a factory over the road from Alvis and built quite a few of these bodies. The wide body part is important because, typically, the hand brake and the gear lever are on the right of the driver’s legs and the clutch and accelerator are well to the centre of the cabin, so in practice the driver is pushed/pulled into the centre.

However, at a pinch three weedy Britishers could still snuggle together in the cabin. Help is on the way though, because there is the classically ’20s dicky seat in the boot in which two large colonials could undoubtedly sit very comfortably, with the legs stretched out full length under the seats in the cabin. When David’s boys were little, if it rained they’d be stuffed into the huge space and the lids shut down — you’d probably get prosecuted these days, or at least suffer trial by women’s magazines.

It has a classically ’20s look about it, two squarish boxes with a bigger one in between them, and the whole lot on a wheel at each corner. Nothing like the later look shared by Alvis, Jaguar, Armstrong Siddeley and Morris 14/6. Nevertheless, where this car really scores is in the unquestionably superior construction, finish and fittings.

Great provenance

David is the Alvis’ sixth owner, and it’s been in his family 43 years. Originally his brother bought it from the fourth owner, who had bought it from a family who passed it around amongst themselves. It’s a car with great provenance.

The original owner was a Kiwi who went to England and bought the car about June 1928. It was registered here on January 16, 1929. That first owner had it for a while then it went to somebody else with the same surname, then to somebody with a different name (daughter with a married name?) at the same address. Then to one other owner, then to David’s brother in 1963. Finally, of course, to David in 1971.

The brother had got interested in boats, having got as far as a strip down and chassis repaint, so David took the project over and reassembled and refurbished as he went. It was all there and all in good order, consequently we have a 77-year-old car that’s had a 10-year overhaul about half way through its life.

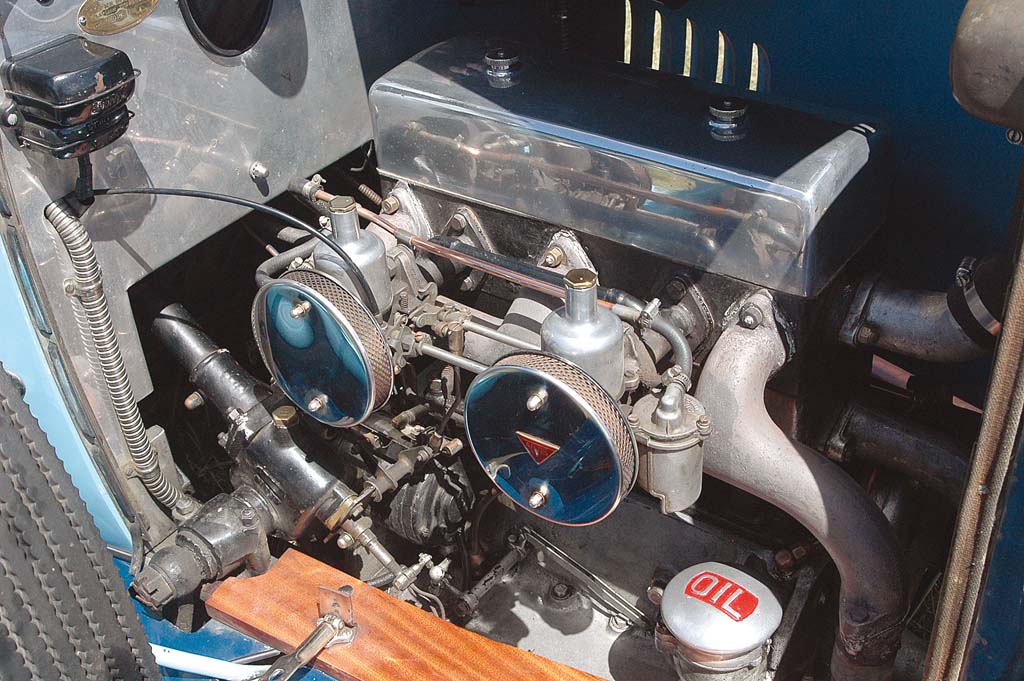

The only modifications have been to fit the later twin SUs and a detachable oil filter. This latter is a commonly fitted device on most vintage cars, but the twin SUs were a safety precaution. The original carburettor was an up draught poised just above the commutator and, having seen a Bentley go up in flames, David is very risk aversive, so on went the SUs from a 1931 model Alvis.

On the road

A real test of these old cars is a drive through Auckland traffic. This car is almost good enough to qualify as an everyday driver — if you’re a true old car lover with time on your hands. It’s got four excellent drum brakes, very good steering, lots of real torque allowing you to wind away from almost dead slow in any cog, and with that comfortable feeling that there aren’t going to be any surprises. This Alvis demonstrates that the pedigreed cars really were better designed and better built, and consequently were superior enough to be worth the extra money, they weren’t built for the hairy mass market where cost was of prime consideration.

But as a consequence they’re heavy, which does take the edge off the performance unless you do a strip down. However, it’s that weighty build quality that gives them a great name, and they’ll go on and on until the last trump sounds.

David has been timed at 116kph (72mph) and he wasn’t flat out, so the 80mph speedo is necessary and that’s almost a mile per year of the car’s life. Take off the heavy guards etc and she’d easily exceed 116 — should you be able to think of a reason to do so.

All of that notwithstanding, David made the comment that at the end of a day driving this car, you are tired because these old girls can’t compete with modern cars — not even the best of the old girls. Shucks, is that non PC? I hope so.

Good driver

I’m going on a bit about what a good driver this Alvis is because I’ve not enjoyed every drive in every old car over the years — some have been pigs and were pigs when they were new — but the ‘name’ marques have always deserved their reputations for not only being good drivers, but also for conferring status on the driver! This is definitely a good driving status car — confirmed by the favourable looks we kept getting as we motored around the suburbs. Of course, it could have been the two aging but distinguished old gents sitting up in the pleasant sunlight, but I guess it really was the singularly pretty car.

I noted that David liked to have about three car lengths minimum between himself and any car in front, and sure enough a (solid) dab on the brakes was then quite sufficient to aid in evasive action as the mandatory slowing up in front to read the radiator badge occurred. Irrespective, however, in the afternoon traffic we bowled along very pleasantly in a thoroughly useable old car showing 12,000 miles (19,312km) since its last rebuild 20-odd years ago.

Just to keep his hand in David is restoring another, very early ’30s Alvis — with a sporty boat-tail body — and has almost finished the wood frame repairs. He also has a very early ’60s Rolls-Royce which appealed to me because, for a change, it’s an understated Rolls, and so one wouldn’t feel impossibly pretentious using it. The Rolls grille is not something that this working class boy feels comfortable behind but, in the case of this car, the balance is just about right and I would enjoy the charade.

Alvis 1920 – 67

There was an era when the British produced cars peculiarly and distinctively British. The expression ‘Best of British’ meant something during the classic era, and classier makers capitalised on this, aiming at giving an implied guarantee of status and quality by virtue of the styling they adopted. Low to the ground (despite tall wheels), with long bonnets, sweeping front guards and lavishly equipped interiors.

Even down-market makers used similar styling to sell some of their models. I had as a first car a 1938 Morris 14/6 that had ‘the look’ — in this car the long bonnet encased a cumbersome cast-iron flathead six. It was extremely reliable, but the cart springs and consequential bone jarring in a pothole meant that ‘the look’ was only skin deep.

However, during the ’20s, Alvis focussed on well-built and well-designed quality performers with distinctly sporting aspirations. Since the firm was founded in 1920 it clearly had the advantage of looking around at the others in the niche it chose to sell in.

Throughout the ’20s Alvis’ were hardly trendsetters, but they were very well made and quickly built a reputation for longevity, sporty performance and sound construction.

The company’s founders — TG John of Siddeley-Deasy and GP H de Freville from DFP — ensured their cars were never aimed at anybody but the upper middle class — who else could afford cars?

In those days there was a lot of inbreeding (so to speak) going on in the British motor industry — all the ‘names’ knew each other. The DFP connection was very important because that was also WO Bentley’s racer of choice, and through this Alvis was a very early pioneer in the use of alloy pistons — one of WO’s gifts, pioneered in DFPs.

There’s absolutely nothing that can be said in favour of warfare, but a tiny argument could be carefully advanced that points to the hugely accelerated development in engineering which warfare stimulates and pays for. All these men I’ve referred to — and more — were British engineers of considerable merit, and aero engines and suchlike proved to be superb test beds for the advanced ideas incorporated in the cars of the ’20s.

By the ’30s the transition to the ‘British look’ had started, and Alvis was designing a range that covered not only quality bread-and-butter cars but also the Eagle series of models. The Silver Eagle, the Crested Eagle and so on leading to the 1938 Alvis 4.3-litre four-door saloon with true 100mph performance. It was called a short chassis saloon, but in reality it was long and low, complete with two side-mounted spares in the wells of the huge front guards.

Following Hitler’s war, Alvis adopted this style exclusively, producing some very fine vehicles in the ’40s and ’50s. Even in the last Alvis — the TE21 — was a handsome car.

Rover bought Alvis in 1965. Alvis is still in Coventry making military hardware but the cars were lost in the general collapse of a formerly thriving industry. I guess Herr Hitler’s VW Beetle had the last laugh — although not quite as loud as the last laugh when VW’s acquired Bentley in 1998.

Words & Photos: Penn McKay