data-animation-override>

“Published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 210”

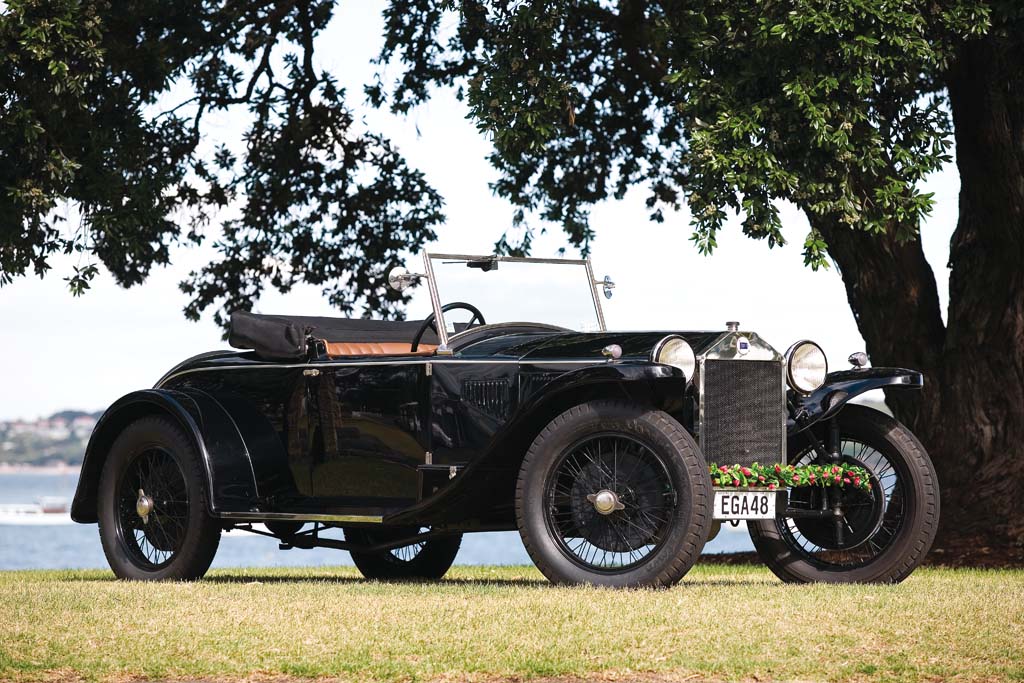

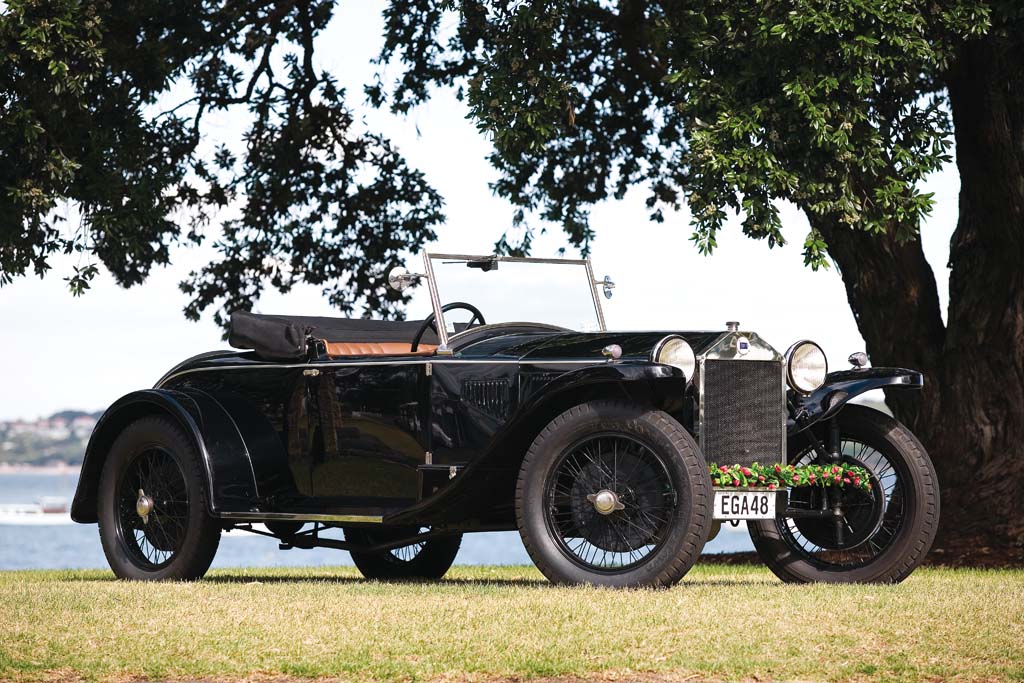

Penn has his bias toward Italian cars reinforced by a superb Series 8 Lancia Lambda

The sharp end of the vintage movement is composed of some very focussed adherents, and few come more focussed than Diane and Keith Humphreys, a couple who plan their recreational driving like the rest of us plan our working life.

Their latest acquisition, our subject Lancia, has a central role in their lives demonstrated by the weave of roses and leaves wound along the car’s front axle — take time to stop and smell the roses, life’s too short. That sentiment was demonstrated in this way by a friend, who clearly felt the symbolism of plastic roses outweighed the lack of anything to sniff, even philosophically.

I think that they’re on the right track and I absolutely loved their Lancia, which is a strong contender for the title of best driving, most interesting vintage I can remember lusting after.

Visually the Lancia Lambda is a very beautiful car no matter what coachwork is sported. But its specs are hugely impressive. Until I’d looked at the Humphreys car then read The Design, Development and Production of the Lancia Lambda by Bill Jamieson, I hadn’t realised the significance of this car, which was to be copied in at least two features by most manufacturers within a couple of decades.

Milestone car

Lancia received a high degree of acceptance for its revolutionary monocoque body, but when Citroen did it in 1935 with the mass production Traction Avant it went broke; the public wasn’t quite ready and the scale of Citroen’s operation was mopping up money that 13,000 Lancia monocoques over 10 years didn’t and couldn’t. Besides, Lancia not only kept other models in production but was also a high-end marque aiming at the wealthy.

Reading the Jamieson book and peering at the car has caused me to realise that Vincenzo Lancia’s design was a very significant step forward in automotive technology. I’ll go further and say that I see these cars as easily rivalling WO Bentley’s prestigious products and, if it comes to that, Messrs Rolls and Royce.

Funnily enough, having come to that comparison, I looked at a Blower Bentley at the recent Kumeu Car Show. It certainly was impressive, and it wasn’t until I’d checked out the front suspension and steering that I could reassure myself that I was still a wise old motoring writer not yet in my dotage. What was it Bugatti said, “The fastest trucks in Europe!” The very competitive Lambda looks a delicate thoroughbred in comparison.

Henry’s Models T and A were epochal cars, but the Lancia wasn’t for every man as a conveyance and quality took precedence over cost. More to the point it set technically innovative standards that others took notice of, including Henry Ford.

Innovative?

With this car, Lancia made two major moves forward. The deletion of the chassis enabled by monocoque body construction, and the newly designed independent front suspension. That said the motor deserves to be hailed as innovative also.

Lancia’s IFS quickly became the new standard worldwide. It impressed everybody with its visual elegance and, more practically, impressed everybody with the hugely improved handling, suspension and the excellent turning circle you suddenly gained. In the Humphreys’ Lambda these facets are instantly noticeable — the improved steering lock alone is a winner.

Keith raced me around Devonport and we travelled and cornered at considerable speed, seemingly well beyond the limits of any other vintage car I’d ever been in. It was at this stage that I really sat up and took notice — well, actually tightening my grip on everything and applied considerable suction. These Lancias really handle.

The sliding-pillar independent front suspension has a tall sliding trunnion housing a coil spring dampened hydraulically in oil, and looking like a telescopic shock. Above it, each guard has a porthole that allows you access to top up the oil, or to dismantle the unit with a special tool supplied with the car. It’s held rigidly at the top and the bottom, with the stub axle mounted partway up it on the moving part of the trunnion and controlled by the oil and the springs (well that’s what I think is happening).

In a world used to cart springs, the change was revolutionary. Every aspect of control, ride and steering was hugely improved, and you can directly experience that on this car.

This radical design was to be a feature of Lancias for the next 40 years, and seeing the set-up graphically illustrates how strong, elegant and lightweight it is compared to the old beam axle and cart-springs set-up.

Monocoque

In eliminating the need for a chassis Lancia put his faith in the concept of a monocoque body. Here it took longer to achieve general acceptance, and that was partly because the technology couldn’t yet produce curved panels — curved panels markedly increase the rigidity — so box sections and bracing built around a transmission tunnel and deeper side sections gave a very strong body with a huge reduction in weight, but it limited the styling concepts.

However, the substantial reduction in avoirdupois meant that quite small motors could be used without losing a competitive edge against the multi-litre motors needed to shift the big and heavy, conventionally built cars of the period.

The Lancia’s transmission tunnel was also a revolutionary idea whose time had come. It’s a central spine (made of a curved panel!) and is a very significant part of the overall bracing. In the four-seater cars it did confine each person’s feet to their allotted space, however, it also allowed the whole car to be considerably lowered.

This resultant low stance cuts the Lambda adrift from its vintage contemporaries, and points the way to the ’30s and ’40s.

Unquestionably the body was the most significant difference in a car full of new ideas. All steel sides from the radiator to the tail consisted of 2mm panels riveted together, and with more steel panels on the outside. Even the radiator shell is part of it, and of course the engine mounting bearers were fundamental to what was termed by Lancia as the ‘trapezoidal’ framework.

However, with these very early monocoque bodies there was another acceptance problem. Car buyers couldn’t commission any body design they desired on this chassis, and this limitation wasn’t overcome until after WWII when stamping technology caught up and structural panels could be shaped any way you wanted. Nevertheless, Lancia survived its bold move and established itself as a very respected car builder. There are people who believe the Lambda to be the most significant design of the 20th Century.

The Motor

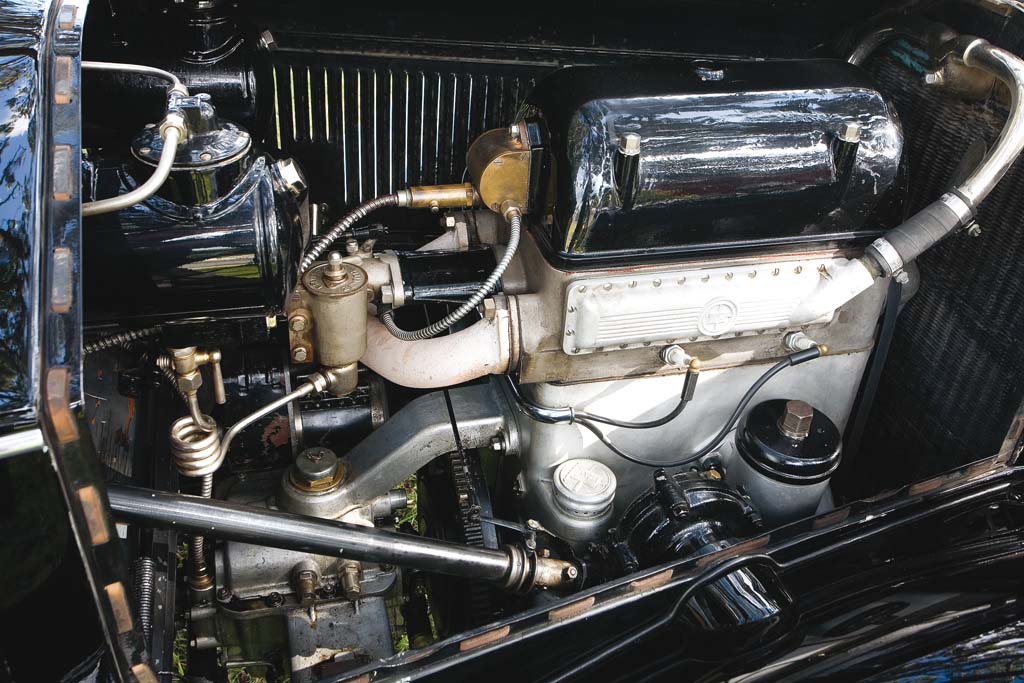

The Lambda’s engine alone would have separated this car from its peers, never mind the IFS and monocoque body.

It consists of three longitudinal pieces with the middle piece being quite thin and commonly called the ‘ham’ (as in the sandwich). The carburettor at the rear feeds all four cylinders through a free-standing manifold feeding a tunnel, and similarly the exhaust manifolds scavenge the cylinders through an exhaust tunnel, both as part of the casting. Lancia also built a V8 this way, and even tried for a V12, but that wasn’t successful and was dropped. The gearbox is accessible from under the bonnet because the motor is so short. It’s an all-alloy block and, consequently, given to corrosion if neglected.

Throughout the nine years that these cars were produced the motor size went from 2170cc to 2370cc, and then to 2570cc, and now 80 years later Australian enthusiasts (I think) have reproduced the Lambda engine block and taken it to 3.0 litres.

Some purists would argue against the 3.0-litre block, however, the only argument can be around ‘originality’ and there are too

many exceptions to that for it be a seriously valid argument. The remanufactured 3.0-litre block is identical in every way to the original 2570cc version, and fits the original cast-iron head exactly. The Humphreys’ car is fitted with a 3.0-litre engine, and it offers seriously torquey performance. I don’t know about the earlier motors, but the 3.0-litre version is exciting, and ideal for crossing the West Island.

The block is a 13-degree V4. In casting the original blocks, four cast-iron cylinder liners were arranged in a mould in staggered V-formation, and molten aluminium was poured around them to produce a single cylinder block and crankcase casting complete with oil filler, breather and oilways. The sump is a similar casting, and the head is cast iron, fitting both the 2570cc and the 3.0-litre block. The single cylinder head covers both pairs of the V, and contains a single overhead cam which is driven by a vertical shaft with bevel gears.

On the nearside of the block there is the magneto, water pump and generator driven in tandem, and on the offside there’s nothing but the elegance of clean simplicity.

A heavy flywheel accepts a pre-engaged starter motor, and slightly further back and detached is the gearbox, which is readily accessed from the engine bay. Sitting above this on the firewall there is an engine oil reservoir which can be drained directly to the sump as a top-up device.

Sensibly somebody has fitted an overdrive unit to this gorgeous car. In this particular car a simple flick to the left or the right of the gear lever in third or fourth engages or disengages the overdrive.

Once you’ve got used to overdrive on a four-speed ’box you’ll have it as an add-on ahead of a stereo.

On the road

Normally a ’20s car feels just like that, but in everyday motoring mode, and admittedly in the hands of the very experienced Keith, this car feels quite different: in effect it feels like a ‘real’ car — more modern. Surges of power indicate a responsiveness that suggests overall lightness. I was impressed by the agility and performance. Unlike your usual cart-sprung vintage, this car was precise and predictable in its movements.

Incidentally, Diane takes her share of the driving; she has now got over the loss of her vintage MG, and I suspect she prefers the Lancia. Every aspect of this car shows the innovative thinking of Vincenzo Lancia and his closely-knit team of associates.

Significantly, Lancia’s very successful racing career (mostly as Fiat’s premier team member), like Wilfred Owen Bentley, strongly influenced his development programme.

The message is clear to me that the best of competition drivers commonly design the best of cars, and there is no doubt in my mind that the 13,000 Lambdas that were produced during the 1920s and very early ’30s were way ahead of their time, and well worth owning if you desire a vintage car with real breeding and style.

Of course, their international price demonstrates this although, that said, the market places more value on some lesser cars — Monaros for instance — and, of course, Rollers, Bentleys and similar ‘name’ cars. This great car costs less than any rental property you could buy in Auckland or, indeed, in many other overpriced places here in Kiwiland. However, I also think that its value is more than guaranteed in Europe, where it has to be an appreciating asset. It’s not a cheap collectible, but nor is it expensive for what it is.

We only have three Lambdas in NZ as far as I know, so if you get a chance to examine one of them have a damned good look, they’re truly great cars.

Words: Penn McKay Photos: Adam Croy