data-animation-override>

“Once again, Graeme Rice looks back on the motoring worlds of 100, 75, 50, and 25 years ago”

Jesse G Vincent – the man behind Packard’s mighty V12 engine

December 1914

On the last evening in 1914 at a New Year’s Eve party at Detroit’s Griswold House, Jesse G Vincent, Packard’s Chief Engineer had something on his mind. Legend has it that a fellow party–goer looked at Vincent and said, “You are going to have twins – I can see it in your eyes.” On New Year’s Day Vincent went back to work and laid down the plans for the famous Packard V12, known as the Twin-Six.

Wily Willy Durant launched the car which would propel him back into control of General Motors when his Chevrolet Division announced the new 490 selling into 1915 for just $490 minus starter and lights. With these rather essential extras, the 490 cost $550.

Hitler and Mussolini – dictators aboard a Lancia, although this one looks like an Astura rather than an Ardea

December 1939

None other than pompous dictator Benito Mussolini road tested the new Lancia Ardea 6V after it was taken to Rome especially for the occasion by one of Lancia’s engineers. This was a smaller version of the Aprilia, powered by a narrow angle V4 903cc engine, developing 21.5kW (28.8bhp) at a remarkably smooth 4600rpm due in part to the use of hemispherical heads.

Autocar tested a Nash powered by a six-cylinder 4790cc ohv Perkins P6 diesel engine. After the magazine recorded some fairly dismal performance readings (0 to 80km/h time of 18.1 seconds, 28 seconds from zero to 100 km/h and 40.5 seconds to reach 112km/h) the upset Perkins engineers examined the motor and found a fault which prevented the throttle opening fully. With this repaired they re-ran the tests, slicing seven seconds off the 0 to 80km/h time – now 11 seconds and almost 10 seconds off the 0 to 100km/h time, now reaching our legal limit in just 19 seconds. Maximum speed was 125km/h with a claimed fuel consumption of 7.43 l/100km (38mpg) at a steady 56km/h. To assist starting the Nash’s 6-volt lighting system was supplemented by a 12 volt one.

The Morrari — seen here at Pukekohe in 1966 / Photo: Terry Marshall

December 1964

There’s always a smart alec – best quote of the month was – ‘These Grand Prix chaps will do anything to increase their car’s performance by reducing weight, why Jack Brabham’s even had his appendix taken out!’

Concern was being expressed at the rising cost of Grand Prix cars and the likely increases if the exotic V12, V16 and V32 engines became a reality for the new 1965 formula. A 1964 car had cost £12,000, a motor £4750, gearboxes £1000, fuel tanks £180, while a set of wheels cost £120, without tyres. A whole season’s racing with a team of two or three cars could easily cost £100,000. Putting it into perspective, a new Ford Falcon Station Wagon cost £1150 –1300 depending on which version one chose.

After November’s speculation about new Jaguar engines, the company came out admitting its subsidiary Coventry-Climax was working on several designs for a new Grand Prix engine for 1965. Up for consideration were a number of multi-cylindered layouts, but any statements regarding new multi-cylinder engines for Jaguar’s sports or saloon cars must be regarded as premature, said the company spokesmen.

What do you call a car with an ex–Peter Whitehead Ferrari Squalo single-seater chassis, a 224kW (300bhp) 327ci (5.4-litre) Chevrolet Corvette V8 motor bolted to a five speed Ferrari gearbox, clothed in a humble Morris Minor low-light body? This was the question the NZ Herald posed for its readers on the 9th of December. The Ferraminor, or Morrari had been built by Glenn Jones and was to be driven in a week’s time at Pukekohe in the saloon car class by Garth Souness.

On the first race of the day the brakes locked up causing a few dramas, but once the Morriarri got into its stride it not only won, but set a new lap record of 1.45.5 seconds – two seconds quicker than Ray Archibald’s Jaguar 3.8.

Suddenly here in NZ there seemed to be a few new cars available without the dreaded overseas funds requirement. Peugeot 404s were available for £1496 complete with an economical (able to return around 8 l/100km at 90km/h (35mpg at 56 mph) 53.7kW (72bhp) four cylinder hemispherical head 1618cc motor, noted for its durability, and with wet sleeves for easy maintenance. Other features included rack and pinion steering, a heater and ventilation system and reclining front seats. Anyone in the know was also aware that Road & Track magazine listed the 404 as one of the best made cars in the world, and Rolls-Royce bought samples for their engineers to study Peugeot’s chassis engineering that made the 404 one of the quietest-running cars on the road.

Cheapest of the new cars was the endearing Fiat 500 Bambina at just £599 complete. Buyers were assured this was a proper car with a quiet-running air-cooled, two cylinder, four-stroke engine with all independent suspension providing a comfortable ride. This was one of Europe’s most popular cars, selling around 500 a day. It came with a sunshine roof, carpets, a heater and demister and a 12 month/ 12,000 mile warranty.

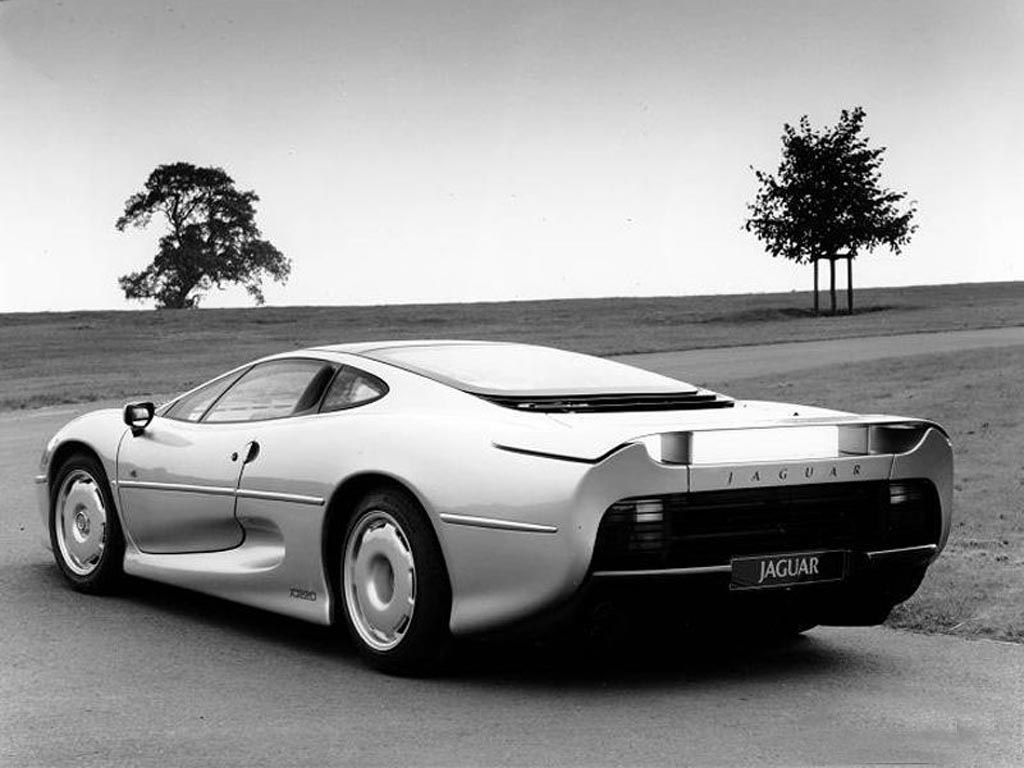

Jaguar’s amazing XK220

December 1989

GM did the deal to snatch Saab from under Fiat’s nose, taking 50 per cent of the company. In reality Fiat wasn’t too upset as the shareholders had separated the profitable Scania truck division out of the equation, leaving the loss-making car company as the lone scalp for a cool $600 million.

Never mind, GM laid out plans to boost Saab production to 200,000 cars a year and have a range of cars that would rival BMW, the smaller Mercedes range and Jaguar by 2000.

The Paris-Dakar rally was scheduled to start from Paris on Christmas Day and finish in Dakar in Senegal 6900 miles or 11,000 kilometres later on 16th January.

Peugeot were aiming for a fourth consecutive victory and were fielding three 405T16s and two 205T16s. Ari Vatanen was their number one driver, joined by Björn Waldegard who was running in his first Paris-Dakar.

Mitsubishi had entered 16 heavily modified short wheelbase Pajeros with Jackie Ickx lined up to drive specially prepared Porsche-engined Lada Samaras. Jacques Laffite was driving a Nissan, with Clay Regazzoni in a Mercedes and Patrick Tambay driving a Range Rover.

When entries closed there were 246 cars, 129 motorcycles and 97 trucks ready to take part in the biggest, longest and deadliest raid of them all.

Jaguar dealers were taking orders accompanied with a deposit of £50,000 for the svelte XJ220, powered by the 3498cc V6 378kW (500 bhp) twin intercooled turbo JVR6 engine. Just 220 cars were planned with another 130 able to be built if demand was there.

With a recession looming buyers needed to be sure the £361,000 coupé was going to be worth the money. Worse for Jaguar were the investors making the purchase expecting the value to inflate over coming years, even though the XJ220 for all its beauty was more than twice the list price of the Ferrari F40!

Believe or not two entrepreneurs bought the remaining stocks of the Sinclair C5, while Sir Clive, convinced all that was wrong with his brain child was that he had released it before its time, was working on a new, larger, version.

Adam Harper had bought 600 C5s convinced they remained unsold and unloved only because of a conspiracy between petrol sellers and the big car companies. He claimed he had sold most his stock for £1000 – well over the original £400. He claimed he was now being approached by collectors and charging £2000 per unit.

Liverpudlian Maurice Levensohn had bought the entire unsold US stock – about half of all the C5s made – 7500 examples out of the total production run of 15,000. He was selling them to Continental resort and Golf Clubs where they could be hired out for transport. He also sold them to invalids and drivers who had lost their licences, and some found homes on the flat cycleways in the Netherlands. He was hoping Sir Clive would make more as he had orders he wasn’t going to be able to fill. Levensohn eventually sold them all, though it took him till 1996 to shift the last ones.

Some highlights of the decade:

1980: Henry Ford II resigns as Ford Chairman – first time since 1906 a Ford isn’t at the helm of the family company.

1981: Franz and Fritz Schlumpf offer to pay their French debts if they can regain possession of their huge collection of Bugattis at Mulhouse.

1982: Colin Chapman dies of a heart attack.

1983: Richard Noble regains the World Land Speed Record for Britain at 633.42 mph.

1984: Nissan announce they will set up a factory to build cars in Britain.

1985: Computer whiz Sir Clive Sinclair crashes on the back of the failed three–wheeler, the C5. Sir William Lyons, creator of Jaguar and architect of some splendid motor car styles dies.

1986: There are now five million Minis squirting about.

1987: VW build their 50 millionth vehicle. Citroën close the door on their garden shed – in other words ditch their quirky 2CV.

1988: Donald Healey dies, creator of the archetypical British Bulldog of a sport car, the Austin-Healey 100/3000. Nigel Mansell begins joining the Ferrari team under Enzo, like driving for the Pope.

1989: Rebirth of Bugatti announced.