data-animation-override>

“There was a time when Formula 1 was comparatively simple — you bought your engine from Cosworth, gearbox from Hewland, and ran up a chassis”

One enthusiast, Peter Connew, built his Formula 1 (F1) car in a London lock-up. The Connew (imagine trying to drum up sponsorship with a name like that) ran a handful of races in late 1972 before funds ran out.

In those days, buying an established team’s cast-off was also an option, but there were still many small outfits, most long since forgotten, that had a go. Prior to the Connew, there had been the Bellasi, while, in 1970, Piers Courage lost his life in a de Tomaso that followed the conventional Cosworth DFV/Hewland route. John Surtees, frustrated by his season with British Racing Motors in 1969, bought a year-old McLaren, and, having already put his toe in the constructor’s water with his F5000 cars, he turned out the first in his line of F1 cars in 1970. He lasted longer than many — the entire decade, in fact — though neither de Tomaso or Bellasi made it past 1970 as F1 constructors.

Chasing the dream

If there was one year that saw kit-car constructors mushroom, it was 1974. Forty years ago, more short-lived équipes turned up to chase the dream than in any other F1season.

Chris Amon, after a year of battling away with the underpowered Tecnos, shunned the advances of both Ferrari and Brabham to go his own way with the Amon AF101. The Amon would be joined by the Hesketh 308, Token’s RJ02, and Trojan’s T103, all these — mainly one-car teams — turning up as and when they could. But we’re not done yet. Lola, hardly a new name to F1, had also done its first ‘Cosworth kit car’ for the new Graham Hill team. Within a year, the first Hill would debut. But back to 1974 for the year-end North American Grands Prix (GPs), both Parnelli and Penske turned up with F1 cars for Mario Andretti and Mark Donohue, respectively.

And we’re still going, because although there was an obvious Kiwi connection with the Amon, there were also New Zealanders involved with the Lyncar 006 and a Japanese-built car that tried to kill its driver. The Lyncar was built for John Nicholson, whose Nicholson-McLaren engine company was doing McLaren’s DFVs, as well as Formula Atlantic BDAs. ‘Johnny Nick’ was himself reigning British Formula Atlantic champion with a Lyncar-BDA, and, after debuting in the Race of Champions, the tiny team was one of 35 cars trying to qualify for 25 spots at the British GP. The Amon wasn’t one of them. The Spanish GP in late April had marked the start of the Amon’s short GP career — Chris qualified the pale blue car 23rd, but it ran out of brakes early, and, after failing to qualify at Monaco, the AF101 was taken away for more development and to try to curb its propensity for shedding wheels.

Thirty years on, Chris, when asked ‘Why pale blue?’, explained it was because there were no cars that colour — “Thank God we didn’t paint it black,” he said, meaning that he would not have wanted to have had the whole affair purported to be representing New Zealand.

However, a few years later, the car was competing regularly in historic races and doing well, its shortcomings sorted, and Chris’ whole view of it had improved considerably. He acknowledges they should have built something much simpler, because they never had the funds to properly develop it. The team returned for the German GP on the original Nürburgring — a track Chris loved.

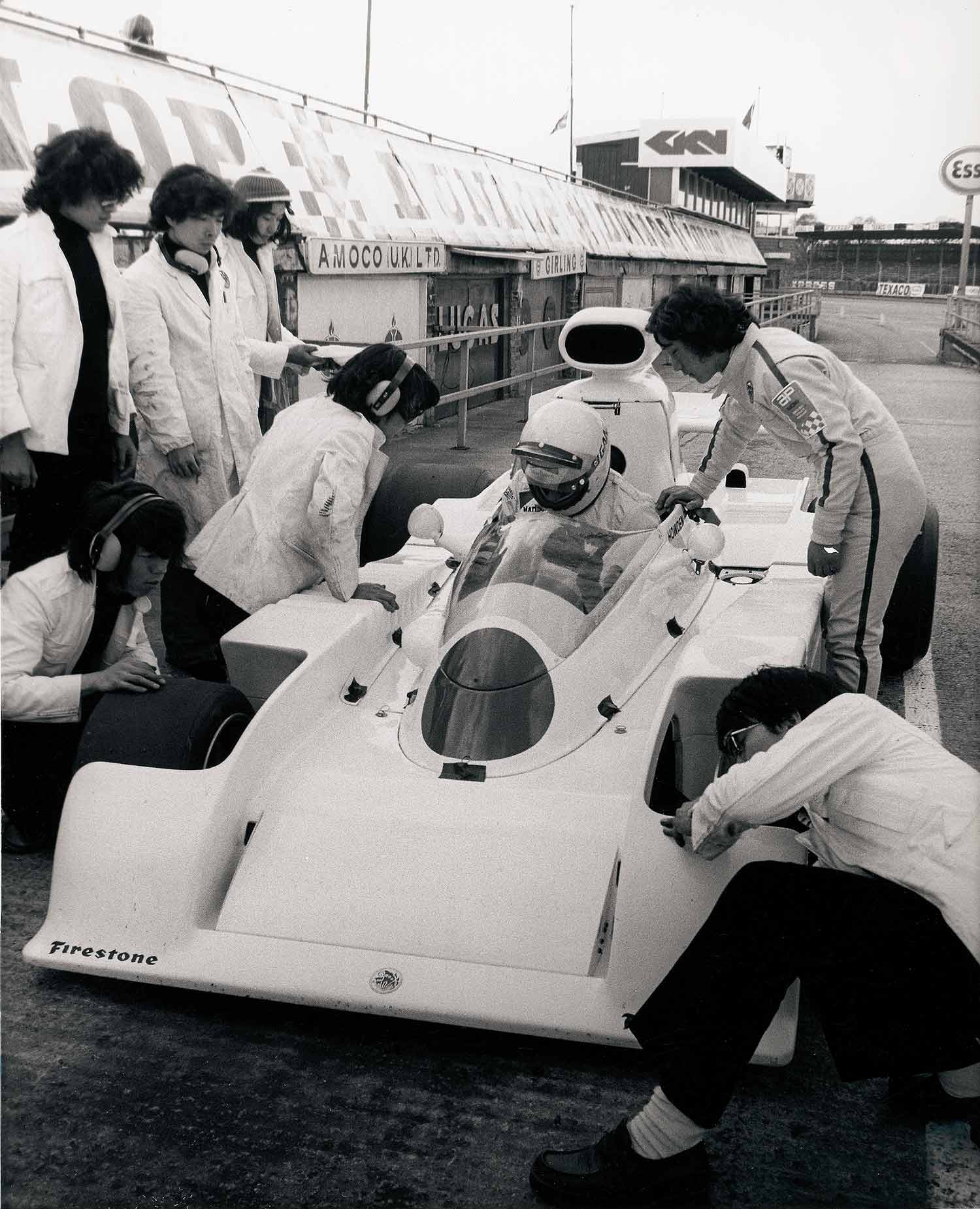

Howden and the Maki

Howden Ganley had run the early GPs of 1974 for March, but then came the mysterious phone call from Japan, and the offer of a large retainer to drive yet another kit car — the Maki. Howden thought it was a prank at first — one of his mates doing a bad impression of an Oriental accent — but it was real, all right. Howden would be on a tidy retainer but had misgivings about the design — that was part of the reason why they’d targeted the Kiwi: a driver with F1 credibility who could also help them develop the car.

The 1974 British GP at Brands Hatch marked its F1 entry and, perhaps not surprisingly given the size of the entry, it was a non-qualifier. There was only a fortnight between the British and the German rounds, but, with a mere 32 cars trying to make the cut, the odds were instantly better.

Howden’s reservations over the suspension design proved well founded with nearly devastating results. It collapsed at the Hatzenbach — very early into a practice lap — and crashed heavily. Howden was sitting in the car in the middle of the track just beyond a fast blind corner. He knew his legs were in a bad way, but of more immediate concern was that the Maki was positioned so precariously that the next car through could easily T-bone him and take him from ‘just bad injuries’ to something much, much worse.

Forty years on, Howden’s recall is crystal clear: “I knew the red flags would eventually come out, but would another car come through at speed before that happened? To my enormous relief I saw a flash of pale blue, and knew I was OK — if the next driver through had not had the reactions of Chris Amon, then …”

The Maki was destroyed, but even worse were Howden’s ankles. It was a long and slow recovery, and, apart from a handful of sports-car races, his days as an open-wheeler driver were over.

He had arrived in England penniless in 1962, and, after working as a mechanic, he saved enough money for an F3 car, then a year in F5000, followed by F1, and long-distance sports cars from 1971 to 1974. Sadly, it all came to a crashing end 40 years ago this month. Maki, meanwhile, hung around until the end of 1976 — two models and zero starts comprised the sum total of its effort.