data-animation-override>

“Donn drives the first BMW sold in New Zealand 46 years ago, while recalling a test he carried out on its sister car in 1968”

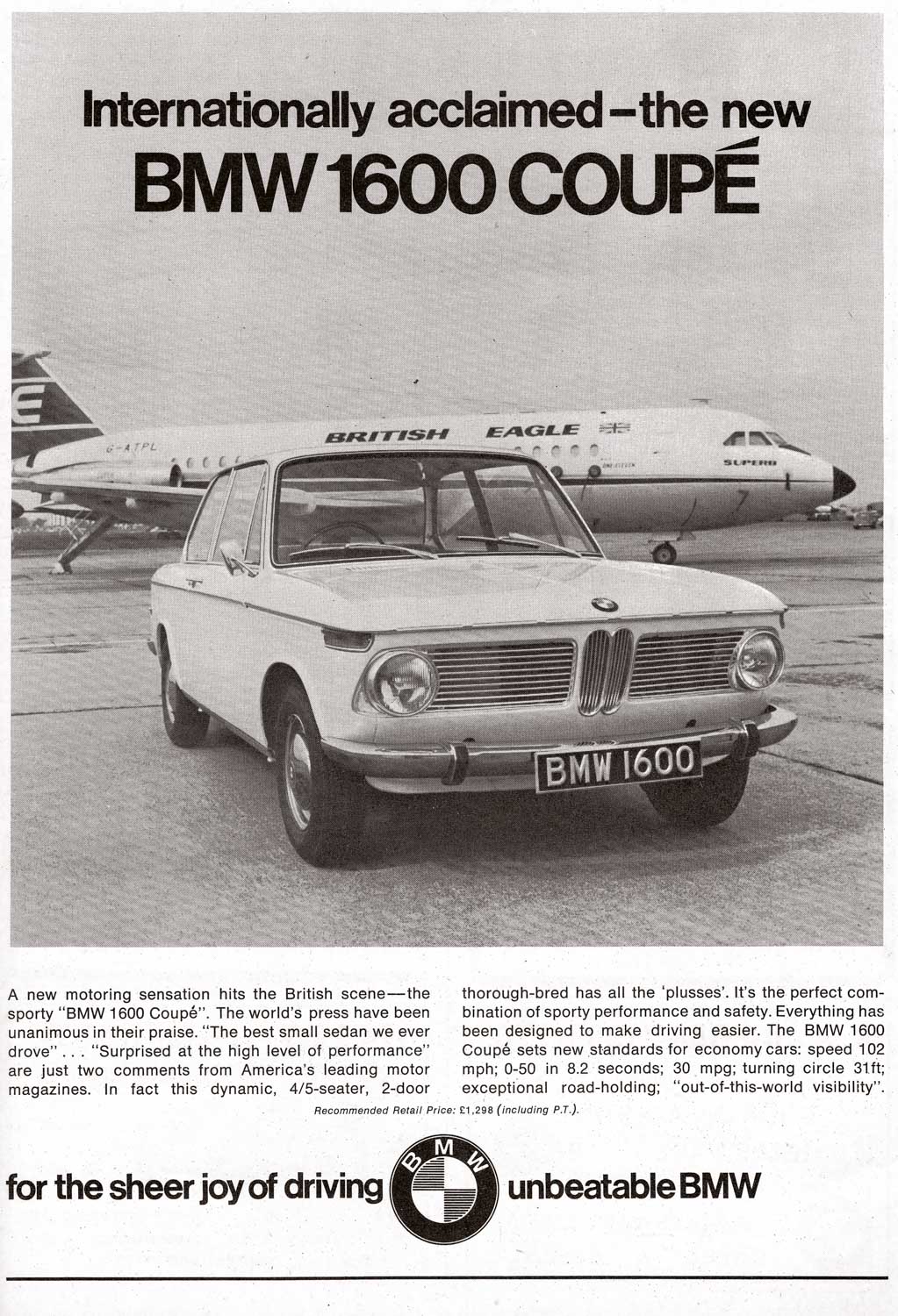

On busy Auckland roads, an immaculate-looking ’60s BMW 1600-2 bearing the plates DE2610 attracts attention wherever it goes. Yet scarcely anyone appreciates the real significance of this compact two-door sedan.

The 1600 marked the turning point for the Munich-based carmaker, and this particular vehicle was the very first BMW to be officially sold in New Zealand — one of three 1600-2s ordered by Ross Jensen in 1967 soon after he had secured the BMW franchise in July that year.

Ross’s motor-racing skills were well known, and his small motor business on Auckland’s Remuera Road dabbled in several European car distributorships, including Austin-Healey, Jensen, the Daimler SP250, Renault, and Alfa Romeo. However, apart from a few privately imported BMW Isetta microcars, 501 sedans, and 700 sedans, the German marque was relatively unknown in New Zealand, but Ross could see the potential. Indeed, he would hold the franchise for 16 years until BMW New Zealand was formed in 1983.

Neue Klasse

Rewind to 1959, a time when Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) was almost broke, and German industrialist Herbert Quandt acquired a 30-per cent stake in the company. The Isetta bubble car may have been an ideal city car, but tiny vehicles usually mean tiny profits and, to add to the company’s financial miseries, an unsuccessful line of expensive eight-cylinder luxury cars did little to improve BMW’s fortunes. Quandt was about to sell his share of BMW to Daimler-Benz in 1961, at considerable financial risk, but changed his mind at the last moment and increased his stake to 50 per cent. Committed to making it work, Quandt would be responsible for reversing the company fortunes and, a year later, the BMW 1500 sedan was launched.

Introduced in 1961, the 1500 was the first of the ‘neue klasse’ (new class), followed by the 1600 in 1964 — both models being four-door sedans. The two-door E10 1600-2 series, built between 1966 and 1977, was a natural progression from the 1500/1600, with the new model sharing the latter car’s 1573cc four-cylinder engine. The 1600-2 was joined by the visually similar 2002, and both were eventually replaced by the E21, the first of BMW’s highly popular 3 Series models.

The total 1600-2 and 2002 production of 861,940 over a 10-year period included about half a million of the smaller-engined model. In addition, there were 4210 Baur cabriolets and 1672 of 2002 turbos. The 1600-2, however, is regarded as the first post-war sports BMW sedan — the name being simplified to 1602 in 1971, with the ‘2’ referring to the model’s two-door body configuration.

The quest for efficiency

The 1600-2 shared the same running gear as the earlier, more conservative-looking, 1600 sedan, and was initially slammed by some observers for being rear-wheel driven when the trend was towards front-wheel drive, especially with smaller cars.

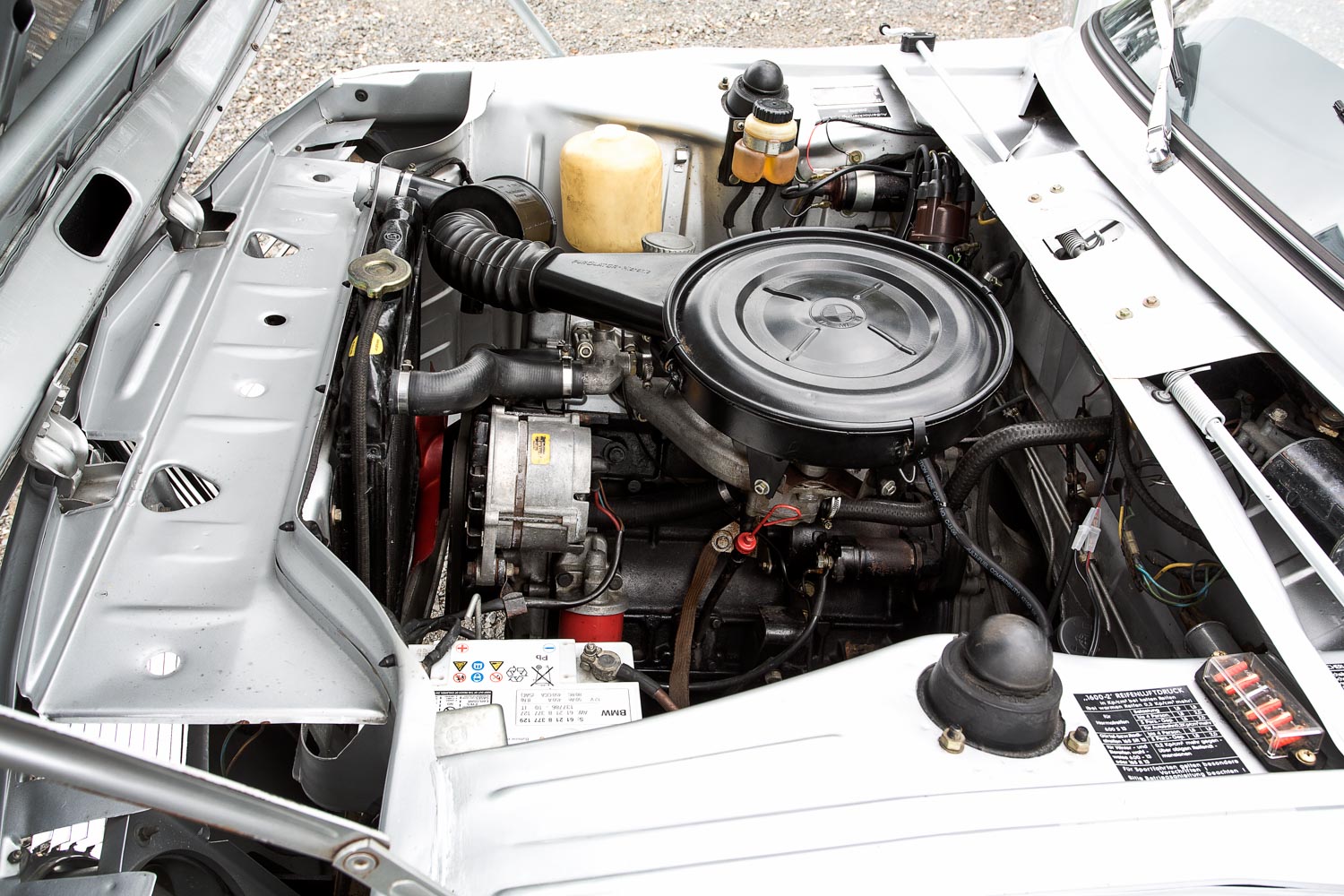

High points included a frisky, single–overhead-cam five-bearing engine with a single Solex carburettor, and independent rear suspension with semi-trailing arms and coil springs. The semi-trailing wishbones pivoted from a strong cross-beam that also supported the differential housing. The 1500/1600 cars were the first BMWs to feature MacPherson-strut front suspension, and the new 1600-2 followed suit.

The car’s high standard of finish and appointments was already winning accolades nearly half a century ago at a time when the Bavarian company’s focus was on quality rather than quantity.

In the quest for efficiency, BMW implemented clever design and manufacturing that allowed the production of more than 20 models from two basic engines and four main body structures. And, since Munich is the centre of the German brewing industry, it seemed logical for bottles of beer to be trollied around the production lines for the workers.

The neue-klasse cars would be a key factor in pushing German home-market BMW sales up by 30 per cent in 1966, placing the marque second to Daimler-Benz in luxury car sales. Additionally, the new cars gained rave reviews in the US, with Car & Driver magazine calling the 1600-2 the best small sedan it had driven, noting it was just like driving an Alfa Romeo that had been built by Germans. Others said it was the best economy car ever offered to an undeserving American public, many of whom still thought the letters ‘BMW’ stood for ‘British Motor Works’!

Legacy

When Royal New Zealand Air Force Air Vice Marshal Richard Bolt visited the 1967 Earls Court Motor Show, he was impressed by the new 1600-2, and ordered one through Jensen Motors under the personal export scheme. The car arrived in Auckland in December 1967 and was registered to Bolt in January 1968. Many years later, BMW technical and service manager John Leggett, who had carried out the first service on the car, tracked down the owner and acquired it. It was then fully restored by Motorsport Services in Parnell. John passed away in the late ’90s, and this 1600-2 was gifted to BMW New Zealand by his estate in 1997.

Alas, the BMW lost its original Kiwi number plates after being deregistered when it was off the road but, in 2012, a set of personalized plates almost put the record right since the ‘O’ on the plate is actually a letter rather than the digit ‘0’. Sadly, because the NZ Transport Agency destroys a vehicle’s history on deregistration, there is now no record of the number of owners the car has had, or the actual mileage, which is currently showing a likely fictitious figure of less than 36,000.

Deja Vu

There was a sense of déjà vu when I drove DE2610 recently because, 45 years earlier, I had road-tested DE2179, the sister car to this 1600, the Bolt vehicle. Fledgling BMW distributor Ross Jensen was a solid supporter of Motorman magazine, right back to my schoolboy days when he regularly advertised in my publication, and he was keen to get me behind the wheel of his new demonstrator. Like DE2610, the Jensen Motors’ car was painted in Polaris Silver and I headlined my story “From Bubble Cars to Aristocrats.” It was a significant road test as, for a number of reasons and unlike today, our shores weren’t exactly bursting with BMWs during that era.

Indeed, devaluation of the New Zealand dollar in 1967 bumped the price of the new BMW 1600-2 up from $3500 to $4300, or more than twice its cost in Germany. A rival Triumph 2000 was $3500 and a Rover 2000 about $100 dearer than the Munich newcomer. There was a mere $400 between the price of the compact BMW and a new Jaguar 240.

However, almost all new cars were in short supply, and British cars were still enjoying a lower tariff rate than the Continental or Japanese brands. Tight import licensing meant local sales of new BMWs did not reflect demand — just 115 were sold in the first five years until 1971. A mere four BMWs were registered in 1967, with 10 sales the following year and 16 in 1969.

Symbolic car

The 1600-2 is a symbolic car, with distinctive, clean lines; an upright stance; and huge greenhouse, all of which makes for amazing all-round visibility, further aided by skinny A, B, and C pillars that would surely struggle to meet modern-day safety crash tests. With this commanding driving position, it is rather like being in an open car, which is a blessing since there is an absence of door mirrors on the Bolt car. Jensen fitted a driver’s door mirror to DE2179 but these were, of course, rare in the ’60s.

At 4242mm, the 1600-2 is almost 400mm shorter than the current F30 BMW 3 Series and weighs only half as much. Although the 1600-2 appears tall, it is almost 33mm lower and, at 1575mm, a remarkable 236mm narrower than the latest 3 Series.

While the bodywork on the Bolt BMW has been restored to new, and the interior is almost as original as you can get, a glance under the front-hinged bonnet reveals the car is not in concours condition.

Yet everything is original, including the shapeless front seats that, perhaps, have lost some of their body over the years since only a short distance is required to find they are lacking lateral support. My 1968 test, however, applauded the seats as being comfortable. I was also impressed by the fore-and-aft adjustment, the knurled knobs that allow partial rake adjustment (with only three positions), and an excellent driving position.

A narrow ring on the skinny plastic steering wheel activates the horn, and padding is used to good effect on the fascia. Quarter windows are opened via knurled knobs, but at cruising speeds the wind noise around the frameless glass doors is only partly a consequence of the passage of time. Ventilation was never a 1600/2002 strong point, but at least the rear side windows hinge open to increase air flow — and wind noise.

Headlight dip and flash are controlled by the left-hand stalk, with the indicator stalk on the right side of the steering column. Pull-out switches for lighting and the two-speed wipers are mounted on the fascia.

Drive DE2610 today and the car comes with a list of instructions: “Drive with choke on until warm, be gentle with the clutch, temperature gauge not accurate when electrics are in use.” The test car in 1968 was reluctant to start once warm, and so too is DE2610 today. Once on the move, the 920kg 1600-2 is responsive, in spite of the modest 64kW (86bhp) engine. It produces peak power at 5700rpm, but is happy enough revving far higher than this.

BMW later introduced a 1600TI version with a 9.5 to 1 compression ratio instead of 8.6 to 1, and 77kW of power at 6000rpm. The lower-powered 1600-2 has a top speed just shy of 160kph and gets to 100kph in just over 13 seconds, while its average fuel consumption of 11.7 litres/100km (24 mpg) is typical of the day.

The four-speed gearbox has a positive if somewhat spongy change, but the lack of a fifth speed means engine noise becomes intrusive at 100kph with the motor spinning at 3800 revs. Reverse gear, next door to first, can easily be wrong-slotted and needs the greater protection of a stronger spring, while the tricky clutch requires learning, especially from a standstill. The maximum gear-change speedometer markings of 26, 48, and 73 miles an hour (42, 77, and 114kph) equate to 6000rpm and can easily be exceeded, even beyond the recommended 6200rpm limit.

My test notes from the ’60s said, “It is easy to spin the wheels during rapid take-offs, and both passenger and driver watch wide-eyed as the speedo swings around the dial.” I reckoned it was fortunate the speedo was highly optimistic, reading 9.6kph fast at 96kph.

There’s no tacho — this would come later with the sports versions like the 2002 — and the unassisted ZF Gemmer worm-and-roller steering, with three and a half turns of the wheel from lock to lock, is only heavy at parking speeds. The vagueness of the steering in the straight-ahead position is something we accept with many older cars. Continental tyres were fitted to the 13-inch diameter, 4.5J steel wheels on the 1968 test car, but today’s Bolt 1600-2 has Michelins.

The ride is firm and hard on small bumps with some pitch and bounce, but better on undulating surfaces. My original test said, “Stability is excellent at high speeds and the steering is reasonably sensitive. When pushed hard, the BMW has high cornering powers, with a little understeer and practically no body roll. On slow corners the inside rear wheel can be spun and lifted. The car is completely controllable on loose metal surfaces, when opposite lock motoring gives the driver not the slightest worry.”

ATE/Dunlop discs are fitted up front with drums at the rear, but the braking system is somewhat unprogressive and feels more like an all-drum set-up. Still, here I go again, confusing ’60s technology with 21st-century advancement.

Well-preserved 1600-2s, 1602s, and 2002s are thin on the ground, especially in New Zealand, where fewer than 300 were sold in eight years. Internationally, it is difficult to find a good condition E10 1600-2 for less than $10,000.

Naturally, from a classic-car standpoint, the 2002 presents a more powerful argument, with its two-litre engine and Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection, beefed-up suspension, reshaped front seats, and extra instrumentation.

However, there is only one car which set BMW on the road to success in New Zealand, and that’s this ex–Richard Bolt 1600-2 — a genuine classic that will thankfully always be lovingly cared for by the local distributor. That’s called preserving your history and your heritage.