Once again, Graeme Rice looks back on the motoring worlds of 100, 75, 50, and 25 years ago

June 1914

Kenelm Lee Guiness spurring his Sunbeam on to victory at the 1914 Tourist Trophy race

While press releases were cabled all around the motoring world celebrating Kenelm Lee Guinness’ win in the International Tourist Trophy race held on the Isle of Man on June 10 and 11, the New Zealand papers were complaining that they still hadn’t received any news of the great Indianapolis 500 race held at the end of May, and here they were in late June, almost five weeks later.

Guinness’ four-cylinder 16-valve 100bhp Sunbeam won the TT, covering 600 miles in 10 hours, 37 minutes, and 49 seconds — an average of 56.4mph.

In spite of complaints about their 56kW 3.3-litre sleeve valve engines laying impenetrable smoke screens, the three car Minerva team all finished. Reiken was second just 20 minutes behind the winning Sunbeam, and Molon was third, 25 minutes behind his team-mate. Potoporo brought the third Minerva home in fifth place. Minervas had been quite prominent in competition, one taking first place in the Swedish Rally held earlier in May, and put up another creditable performance in the Austrian Alpine Trial later in June.

After an amazing performance, W O Bentley’s very effective little 2-litre DFP with its aluminium pistons finished in sixth place earning his franchise huge publicity. As ‘W O’ said in his autobiography, the press love a David and Goliath story and the performance of his DFP certainly generated a large number of enquiries. As luck would have it W O and his brother had a bare eight weeks to get their DFP TT Sports model into the showroom and recouping some of the development and racing costs, when the curtain came down on motoring for pleasure.

75 cars started in the Austrian Automobile Club’s third Alpine Trial with high anticipation that someone would take the monstrous and elaborate Challenge Trophy home after having won three times. After 1821 miles over eight daily stages, climbing 30 Alpine passes and completing a ten kilometre speed test at Wels in Upper Austria there were, unbelievably, five winners each of which could claim the trophy and 10,000 Austrian Kronen in prize money.

50 cars finished, 19 with clean sheets. Both the Audi and Hansa teams were placed first equal. The individual winners were Graumuller, Obruda and Lange, all in Audis, Minerva founder Sylvain de Jong, and Count Alexander Kolowrat, driving a Laurin & Klement. Audi owner, August Horch, made strong claims for the Trophy, based on his team’s aggregate performance over the last three Trials, but coming in to keep the peace, organisers opted to keep the original trophy and make five copies for each of the winners – a slight problem for the poor organisers, who had to find an additional 40,000 Austrian Kronen.

The big story of the 1914 Alpine was the 400 mile overnight reconnaissance undertaken by the redoubtable Rolls-Royce privateer, James Radley. At the end of the first day, Radley arrived at Innsbruck in his Rolls-Royce Alpine Eagle well ahead of the rest of the field. Having been told the Turracher Hohe pass was steeper than the troublesome Katschberg he grabbed a press Rolls and drove over the dreaded Turracher Hohe in the dark, after a 250 mile drive, coping with limited headlights, no street lights and a lack of sleep. He arrived back at Innsbruck the following morning just in time to grab a snack, freshen up and leap into his own car for the second day’s run. In spite of the exertion, Radley was one of the 19 who finished the Trial with a clean sheet.

So many great plans for new cars, motor races and rallies were about to be put on hold in a most forceful manner from July 1914 until early 1919 with the firing of two shots in Sarajevo on a sunny summer afternoon.

It was the 28th of June 1914, when Arch-Duke Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, were shot while attempting to visit a hospital for wounded soldiers. Their borrowed Austrian Graf & Stift had supposedly made a wrong turn and was attempting to reverse when an opportunist student, Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Serbian Nationalist organisation, the Black Hand, fired two shots. One pierced the Arch-Duke’s neck and spinal cord, while the other killed the Duchess.

Mercedes mechanic, test driver and racing driver Otto Merz was driving the third car in the procession. By all accounts a tremendously strong man, Merz ran forward and lifted the dying Arch-Duke out of the car and ran into the nearest house with the aristocrat over his shoulder. A month later most of Europe was at war. After the war Merz returned to Mercedes to test drive cars and race. Moderately successful, he died in 1933 after rolling his Mercedes while practising for the Avusrennen in Berlin.

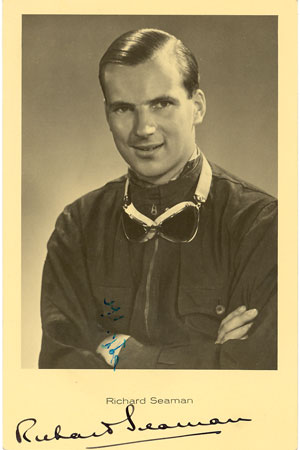

June 1939

Richard Seaman was seen as a true motorsport hero by many pre-war British race fans

If there was ever a black edition of a motoring magazine it was The Autocar of 30 June 1939 which contained no less than five separate articles about Richard Seaman’s tragic death on lap 22 of the Belgian Grand Prix just five days earlier. It had been an epic, rain-soaked race, the leaders Muller and Nuvolari, driving Auto Unions, mixing it with Caracciola, Seaman and Lang driving Mercedes-Benz. For twenty laps they fought for the first six places. Two of the previous rain-masters, Caracciola and Nuvolari, spun off on laps seven and 28 respectively leaving the younger Lang and Seaman to chase down the obstructive Auto Union of Hermann Muller.

By lap ten Seaman had gained the lead and on lap 17 he was leading Lang by 17 seconds when he pitted for fuel. Lang pitted a couple of laps later, leaving Seaman with a 23 second lead on a drying track. On lap 22 Seaman spun while accelerating out of Club corner, and his Mercedes ricocheted off one tree into another. It wrapped itself around the trunk, crushing the cockpit, and trapping a concussed Seaman inside a car already on fire, fuelled by petrol gushing out of the punctured fuel lines which were pressurised by the full tanks. Help arrived soon enough, but tragically no one knew how to remove the Mercedes steering wheel to get Seaman out. It was almost five minutes before the young Englishman was freed from the inferno. That night he succumbed to extensive third degree burns, leaving his wife Erica Popp grieving, widowed after just seven months, and a mother full of mixed emotions. She hated her son racing for a German team, and had refused to attend his wedding to a German girl.

It was birthday time for the family of Standard boss, Captain John Black. His firm was riding high on the success of the Flying Standard range and the reception to the new Flying Eight. Captain John Black created two special cars; one as a present for his 17-year old daughter Rosalind and the second as a present for his wife.

Rosalind’s car, a Flying Eight Drophead, seemed relatively standard except for fog and driving lights, and a chrome radiator surround. Lady Black’s car foreshadowed the postwar razor edge styling of the Triumph Renown and Mayflower. It was built on a Jaguar 3½-litre chassis with saloon coachwork by Mulliners. Novel features were the thin roof structure which gave the car a low look, but retained plenty of headroom. Adding to the slim look were the thin chrome ‘A’ pillars and chrome frames around the windows. The rear compartment was fitted out with state of the art equipment; picnic tables, concealed lighting, electric drive for raising or lowering the limousine division, pillows, cushions and a Dictaphone.

Rolls-Royce showed a very similar body on a Wraith chassis, the coachwork being carried out by Freestone & Webb. This car featured a sunroof, fitted luggage, a radio set, picnic tables and lights which illuminated the running boards at night.

Pierre Wimille and Pierre Veyron drove a supercharged Bugatti Type 57C ‘Tank’ to victory in the 1939 Le Mans – Bugatti’s last big victory. A Delage finished in second place. Two V12 Lagondas ran to team orders, perhaps in hindsight too conservative as the cars were ordered to run below their full potential, and finished a creditable third (Arthur Dobson and Charles Brackenbury), and fourth (Lords Selsdon and Waleran) ten laps down on the winner.

In the same week the latest version of the Lagonda V12 saloon was tested by The Autocar. Costing £1000 with its in-house bodywork, the big Lagonda weighed in at just over two tons ready for the road. In spite of the weight, the 4,480cc engine propelled the V12 up to a genuine 160km/h and from 0 to 50 km/h in 4.9 seconds and up to our speed limit in 14.6seconds, all at a cost of 13 to 15 mpg.

June 1964

The ex-Paddy Hopkirk rally-winning Austin-Healey 3000

With two deaths resulting from a fiery third lap pile up when Dave MacDonald’s evil-handling Mickey Thompson car spun in front of the car of Eddie Sachs and and burst into flames, this wasn’t the happiest Indy 500.

To make matters worse another five cars smashed into the wrecks, resulting in the red flag being brought out to stop the race, the first time since 1926 this had happened. On that occasion it had been caused by torrential rain.

Later in the race Parnelli Jones’ car caught fire while refuelling in the pits. This generated the iconic photo of Jones launching himself out of the burning cockpit arms fully stretched, before rolling around on the ground to put out the flames.

A J Foyt went on to take a win for the big Indy Roadsters, doing 500 miles on one set of tyres.

Indianapolis 1964 was a race that generated many post-mortems, notably the fiery deaths, the pit lane fire and the Firestone versus Dunlop tyre post mortem, which got downright personal. This revealed a lot of unhappiness between Ford and Colin Chapman, owing to Chapman’s insistence that he use untried Dunlop tyres instead of the tried and true Firestones. His obstinacy almost single handedly ensured Ford’s one million dollar engine investment turned out be a waste of money, as all the Dunlop tyred cars ran slow or pulled out with tyre issues. While Ford smarted, the most charitable thought given on Chapman’s behalf was that he had failed to realise that the brand of tyres you use to qualify are the same brand you have to use to run the race. In practice the Dunlops were running at 270 degrees after just four laps, while in comparison, the Firestones were running at 200-210 degrees.

As the race progressed the Dunlops broke up, shredded, or went out of balance so badly the vibration resulted in the rear suspension arm on Jim Clark’s Lotus breaking.

Chapman claimed the Dunlops gave as much performance as the Firestones and he preferred to use a British product.

Paddy Hopkirk had an outright win in the Austrian Alpine Rally driving a venerable Austin-Healey 3000 with the ARX91 number plate, built by the BMC Competitions department in 1963 but not registered until April 1964. Fifty years later this magnificent old campaigner sold at auction for an amazing £242,000.

In spite of being woken for early starts and docked ten points every day for turning up late, Hopkirk and navigator Henry Liddon got the big Healey through every stage without penalty. This was a rally that was full of the classic old passes that had been used since the first rally run in 1910 – the rough, steep Turrach, the treacherously stony Solker Pass and ultimately the majestic climb of the enormous Grossglockner, run at night. In fact the Healey performed so well it was only beaten into a class win by a Ferrari GTO.

In another attempt to get the ill-fated Gordon-Keeble onto the market a group called the Eton Motor Group from Slough was brought in. By now the Gordon-Keeble was a refined machine, featuring a bigger 300bhp Chev Corvette engine mated to a GM transmission and installed in a steel frame, with a de Dion rear axle and clothed in cheaper glass-fibre bodywork. The price was down from £3800 to £2900, but even so it was too much for some especially as Euro-American hybrids weren’t exactly uncommon in the mid-1960s. By late 1965 just 93 cars were built.

It was smiling faces all around as the marriage between Chrysler and Rootes was finalised. Gathered at the table were Baron ‘Billy’ Rootes, Chairman of the Rootes Group, his brother and Deputy Chairman Sir Reginald Rootes, Chrysler President Lynn Townsend and Chrysler VP Irving Minnett. Under the deal Chrysler were to acquire 30 per cent of ordinary voting Rootes shares and 50 per cent of the A non-voting shares, effectively giving them control. Chrysler were well aware that their expansion plans for Europe were lagging well behind Ford and GM who had both sold over a million cars there in 1963. Through Simca, Chrysler’s French subsidiary, just 250,000 cars had been sold, with another 93,000 coming from other exports. As it turned out, the deal was done just in time as six months later the 70 year old Baron Rootes, born on the 17 August 1894, died on 12th December.

June 1989

The Mazda MX-5 – a modern alternative to the classic Lotus Elan?

Rumours were circulating that Alain Prost, frustrated by Ayrton Senna’s antics and the apparent reluctance of Ron Dennis to intervene, was about to announce his retirement from Formula One racing. He had been with McLaren for six years, given them two world drivers’ championships and felt he was lacking the necessary aggression to compete effectively. In spite of his self-doubt Prost was on his way to his third world drivers’ championship this year.

His long term plan was to put together a new F1 team with Ferrari designer John Barnard whose contract with Enzo was expiring in October. Renault was the likely source for the new team’s V10 engines.

By the 21st, journalists had hoped for some confirmation from Prost, but none was forthcoming and sources suggested he was still waiting on Ferrari and John Barnard to go public about their agreement coming to an end.

Finally it was announced that Barnard and Ferrari were parting ways, effectively putting an end to Enzo’s last master plan of having the Englishman take over technical direction at Ferrari. His negotiated retainer was rumoured to have been around five million dollars, the highest ever paid to a racing car designer. Still, the idea of a tie-up with Prost died when the new venture failed to attract any sponsorship.

“We drive the ragtops the world is queuing for!” Trumpeted the cover of Autocar magazine for June 7th, 1989. Truth was there was just one ragtop the world was waiting for and it wasn’t the Mercedes-Benz 500SL with its 17 micro-processors and 15 electric motors to raise and lower the hood, nor was it the exclusive and horrendously expensive to run Ferrari Mondial in spite of its four year wait for delivery. Instead it was a car that had somehow managed to convincingly reinvent the simple pleasures of sporty, wind in the face motoring.

Mazda’s MX-5 was proving the truth of the old saying keep it simple, keep it fun, keep it affordable. The best thing about the MX-5 was that it offered 1960s style and fun with 1990s mechanicals and sophistication and just gave the appearance of being a winner. English dealers were taking orders nine months ahead of the MX-5 arriving in any quantity. Some dealers had turned potential customers away, fearing embarrassment if the promised numbers of MX-5s didn’t arrive. US dealers could have sold over 3000 in the first month and now had waiting lists.

It got rave reviews – “From any angle the MX-5 looks sensational,” said one tester. “Deserves to become the new version of the classic 1962 Lotus Elan!” said another. In a dig at the new front wheel drive Lotus Elan one commentator stated, “The MX-5 undercuts the new Lotus Elan by more than £3000, but more importantly it’s a beautifully balanced car with its front engine and rear wheel drive layout.” Another said, “It gives you the illusion of a classic sports car, low seats, high transmission tunnel and short gear lever. It’s a car you sit in – not on.”

With a maximum speed of 188kph from its 1.6-litre motor, it was generally agreed that there would always be faster straight line cars than the MX-5, but it would delight its drivers on twisty roads where its superb handling, roadholding and ability to corner flat would be the source of constant entertainment. Shades of the reason why the MG TC conquered the hearts and minds of those American servicemen at the end of WW2.

All good news for Mazda – they’d invested around £600 million in recreating the spirit of the great British sports car. They were going to have to crank production up to 4000 cars a month to pay down that massive investment. 25 years on we can say thank goodness one motoring manufacturer took the gamble.

Three firsts were scored by McLaren-Honda at the US Grand Prix. Alain Prost had his first victory of the season and for the first time Ayrton Senna’s car, after leading for 33 laps, died courtesy of gremlins deep in the electrics of the Honda V10. Prost’s uncharacteristic big crash in practice on the Saturday was another first for the team. The little Professor rarely made those sorts of mistakes, it had been five years since the previous one.

Senna had been in devastating form, surpassing Jim Clark’s record of 34 pole positions plus putting in the fastest lap of 1 minute 30.1 seconds – 1.5 seconds faster than Prost. However Prost was at the height of his suspicions about Senna being given better engines, an impression not dispelled when, at a press conference intended to dispel the controversy, the Honda engine boss referred to the two drivers as Ayrton and Prost.

Forty-two year old ex-F1 World Champion Driver Emerson Fittipaldi became the first one-million dollar winner at Indianapolis but did it in controversial style. Coming up on a back marker, both Fittipaldi and Al Unser Jnr tried to take the same line to get past. The result was their wheels touched and Unser spun into the wall – his race over, while Fittipaldi managed to hang on to his Penske-Chevrolet to take the chequered flag at an average of 167.58mph, while Unser in the Lola-Chev was credited with second place, as he was six laps ahead of third place man Boesel in a Lola-Judd. In a heart-warming gesture which amazed the European journalists Unser raised arms and gave Fittipaldi a thumbs-up salute with a broad grin as Fittipaldi passed him on his slow down lap. “Can you imagine Prost and Senna doing that??” asked one reporter.

Jaguar’s new XJR-10 was beaten by the two V8 5-litre turbocharged Sauber Mercedes ‘Silver Arrows’ at Le Mans. Sadly there wasn’t a repeat of Jaguar’s 1988 victory which might have heralded a return to their string of five 1950s wins, in spite of the XJR-10’s new twin turbo, 700bhp, 3.0-litre V6 looking very menacing in practice.