Every car’s got one, but have you ever wondered what the process is for how an engine block is made? We spent a day with the only New Zealand engine block manufactured to find out.

In the beginning

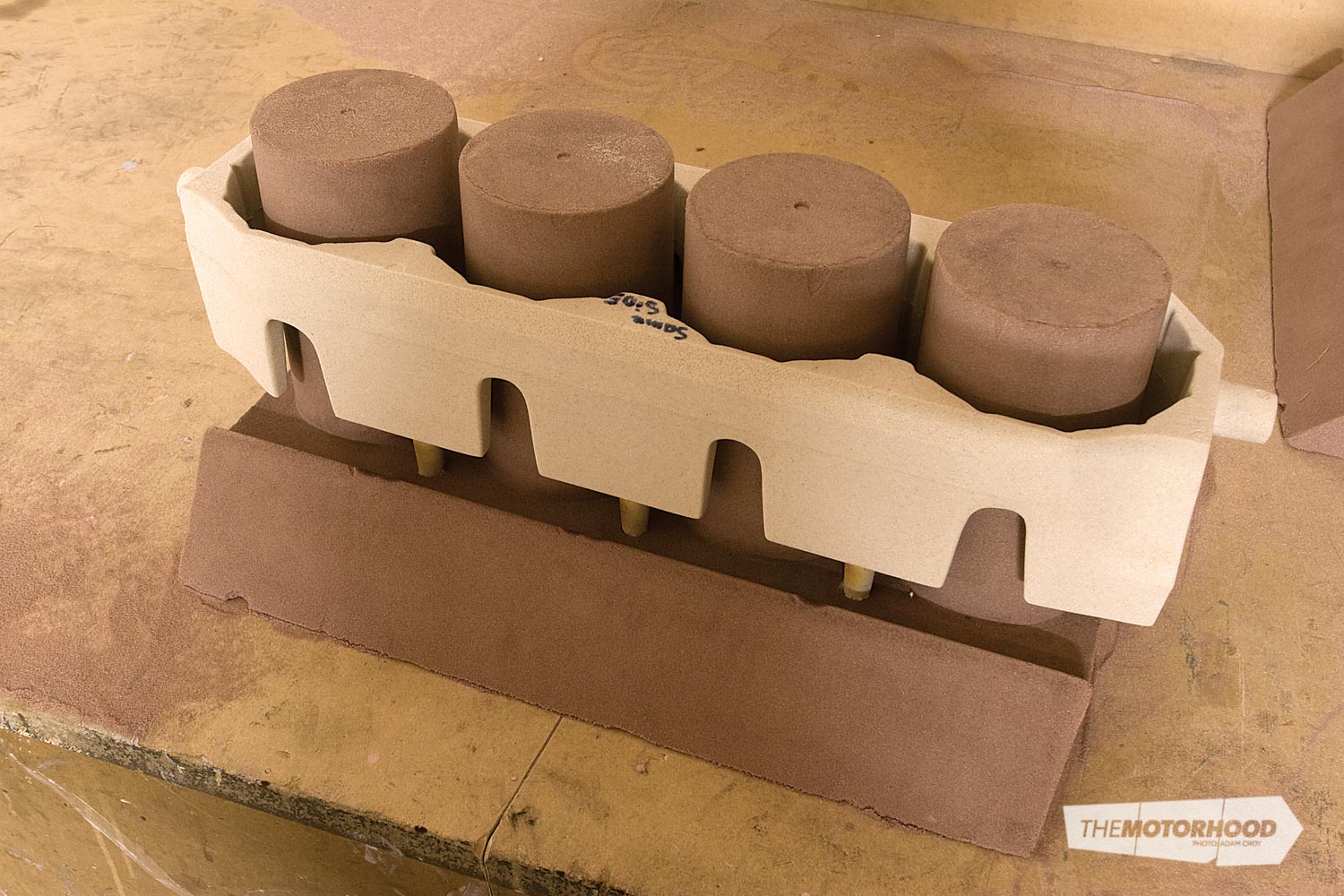

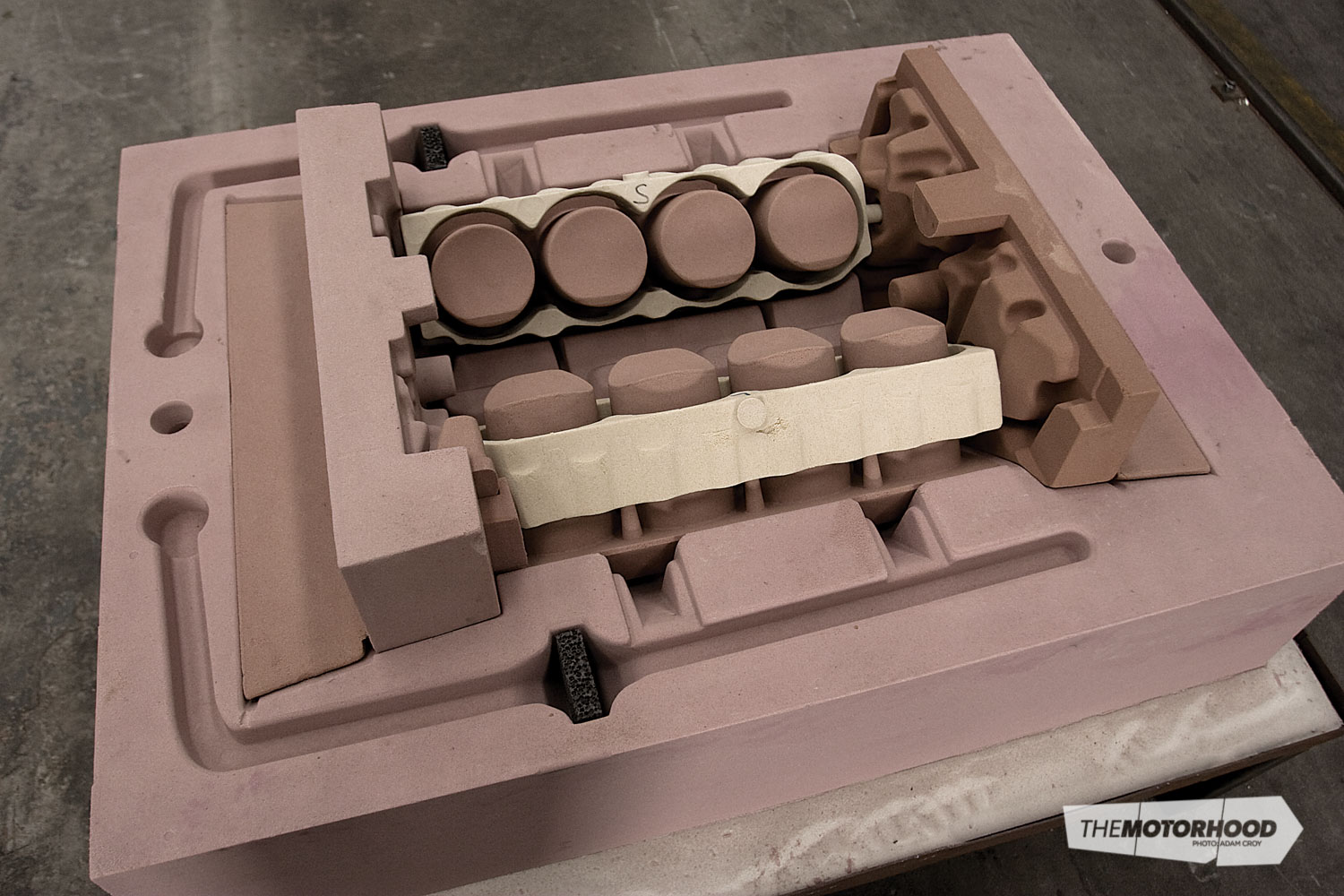

The process used to create the blocks, and many other automotive parts, is called air-set sand casting. Air-set sand casting is a process by which sand mixed with adhesive is poured and pressed into patterns to create solid moulds — just like making a bucket you’d use to build a sand castle.

The patterns, which are made from wood, steel, and bondo, have been refined over years of development and research, and Katipo recently introduced new computerized techniques to speed up pattern development.

Creating a wooden template of an engine block is not as easy as it sounds, because it’s like thinking in ‘reverse 3D’. The pattern produces a mould cavity in sand that is filled by molten aluminium. And for the cylinder bore holes and the water jacket, you have to make cores of sand and place them very accurately in the mould to prevent the molten aluminium filling that space. Fortunately, a top-flight tooling-development team, have solved these complicated problems.

Because the business making these blocks specializes in aluminium blocks, being based in New Zealand is ideal, as we have a great supply of high-quality aluminium thanks to the Comalco smelter in the South Island and Glucina Alloys in West Auckland.

About twice a week the foundry melts 800kg of aluminium alloyed with 7.5-per-cent silicon and minor amounts of magnesium, titanium, and strontium. The metal is cleaned with a flux, after which the dross is drawn off. Finally the hydrogen, which weakens the casting, is removed by blowing nitrogen through the melt.

The molten aluminium, at a temperature of 700 degrees celsius is poured very carefully into the mould, the idea being to prevent any turbulence, which creates oxide dross that will greatly reduce the strength of the casting.

According to the foundry manager, the difference between a good foundry worker and a bad one is the amount of alloy that ends up on the floor. He should know: before looking after this foundry, he worked in a variety of similar roles, the most notable being with Rolls-Royce Aerospace. And given that he’s therefore probably correct about what distinguishes a good foundry worker, the guys here must be first-class, because not a drop of alloy landed anywhere it shouldn’t have while we were there.

When poured, the molten aluminium flows gently through the mould from the bottom up, venting air and gases through the top. This is essential, because any bubbles that are poured into the mould will result in a cavity or porous region in the finished product.

Once the mould is filled, an exothermic mixture is poured over the ‘risers’ atop the moulds. This mixture lights off and keeps the risers molten. Their purpose is to supply aluminium to the parts of the casting that are solidifying and shrinking. If the risers weren’t there or solidified prematurely, the casting would be full of shrinkage holes.

On average, the aluminium shrinks 0.7 per cent as it cools, so the moulds are created slightly larger than the size the final product needs to be. The plus side of the shrinkage is that once the cooling process is completed (in this case it’s overnight), the moulds are easier to remove from the finished product than they would be if they were still tight. In saying that, the moulds are only used once before being broken up — yes, this is a very resource-consuming process.

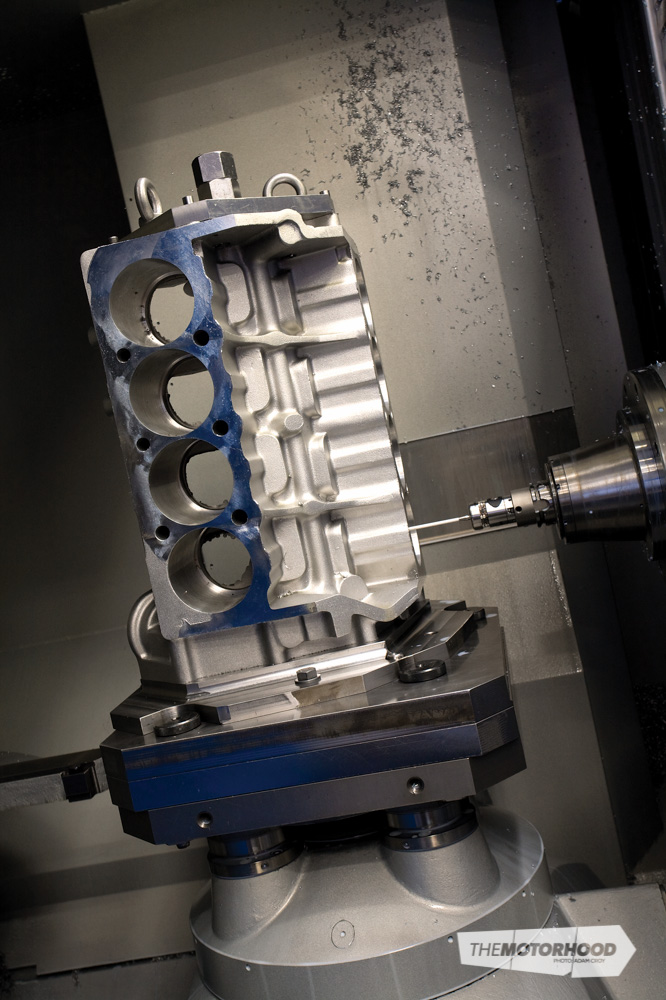

Once the castings are knocked out of the moulds they are fettled and cleaned ready for machining, which is which is also done on site by the foundry crew.

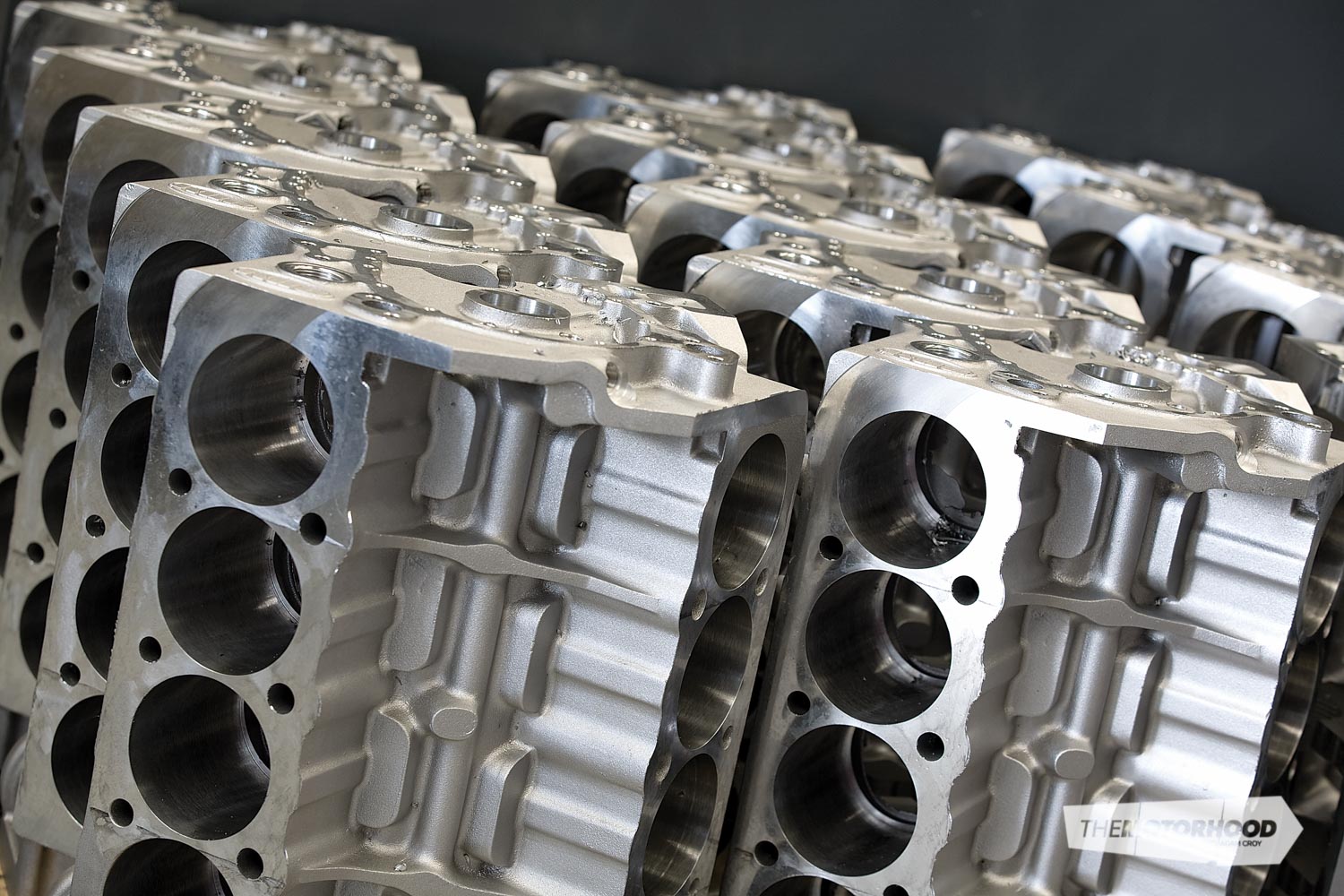

Around eight blocks are made per batch or heat. Although this number could easily be doubled, the work requires a lot of attention, so doing it in short batches is way to keep the quality top-notch.

Machining time

Each block is assigned a stock number, which stays with it until it is exported. This number allows the manufacturer to keep track of which step each block is up to, and also specifies which batch of aluminium it was poured from, should any defects occur.

Every block is subjected to an eight-step machining process carried out in a CNC horizontal-machining centre. Accuracy is critical at this point. For example, the manufacturer’s US customers demand that the crankshaft tunnel has a maximum ovality of not more than three ten-thousandths of an inch. Remarkably, this is always achieved.

After honing, the blocks are packed and dispatched to the US and Australia, so the business is doing its bit for our ailing economy.

This article was originally published in NZV8 Issue No. 52. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: