Graeme Rice’s very first piece for New Zealand Classic Car appeared in our March 1992 edition. Back then, Graeme’s column was entitled ‘Don’t Look Back’, and it dealt with a single, different year each month — the first being 1974. Over the years the column developed into the present ‘Timelines’ format. This month’s Timelines will be Graeme’s last so, for the very last time, he looks back on the motoring worlds of 100, 75, 50, and 25 years ago

March 1915

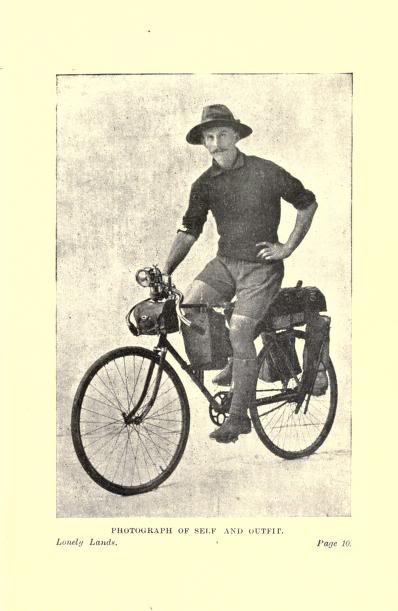

Francis Birtles — early Australian adventurer

Francis Birtles — champion cyclist and long-distance traveler — left Sydney for his overland trip to Port Darwin. His first supply depot was in the north-west tip of New South Wales. That would take him across to Alice Springs. Halfway between Ayers Rock and Port Darwin he would be met by a camel team with fresh supplies. In total, his trip was planned to take two years. By car?

Obviously some English gentry weren’t taking the war in Europe as anything too disruptive where motoring holidays in France were concerned. That prompted a warning from motoring observer Max Pemberton. “They should change their minds at the first moment possible,” said Mr Pemberton. “Our armed forces are still commandeering cars and paying very bad prices for them. A limousine which had cost £1620 and was just three months old had been taken by the army near Armentieres. Finally, after much delay, payment was forthcoming in the form of a cheque for £620 — depreciation with a vengeance!” Apparently the owner was a very rich man and a very good patriot who laughed it off saying he’d just given two 1500 pounders to the national service and promptly rang to order a new car.

March 1940

A wartime salute from the AA

Wartime desperation for iron and steel threw up a novel suggestion from the New Zealand Automobile Association. “Why,” asked their spokesman, “are we the only country outside Great Britain currently rationing petrol, when we import iron at around £33 a ton from Great Britain, and £40 a ton from the US, then waste around 100 tons of it making new number plates for the 307,000 vehicles on our roads? Why are we forced to go without petrol yet are the only country wasting iron on replacing perfectly good number plates with new ones?”

Enzo Ferrari’s workers were on the verge of completing what would, in normal circumstances, have been the first Ferrari sports cars to take part in a race. Unfortunately after Enzo’s dismissal by the Alfa Romeo bosses in 1939, albeit with a generous severance agreement, he was prevented from building cars in competition to the 29-year-old Milanese firm. Chomping at the bit when he saw the Orsi family moving Maserati production into his territory, and heard of Wilbur Shaw’s victory in the Indianapolis 500 in a Maserati, Enzo didn’t take too much persuading when approached in December 1939 by 21-year-old motorcycling champion Alberto Ascari and his friend Marchese Machiaveli di Modena. They had the idea of building a new Italian car to compete in the 1940 Mille Miglia. The deal was done on Christmas Eve 1939, and as soon as he was able to Massimino, Ferrari’s best designer, began work on redesigning a pair of Fiat 508 Balillas. These cars had hydraulic brakes, a four-speed transmission, and independent front suspension. Massimino set about creating a new engine block that would take two modified 508 cylinder heads giving a highly effective straight-eight of 1.5-litres. Labelled the Tipo 815, and fitted with advanced all-enveloping bodywork, the cars were finished ahead of schedule, ready for testing prior to the race on April 28.

March 1965

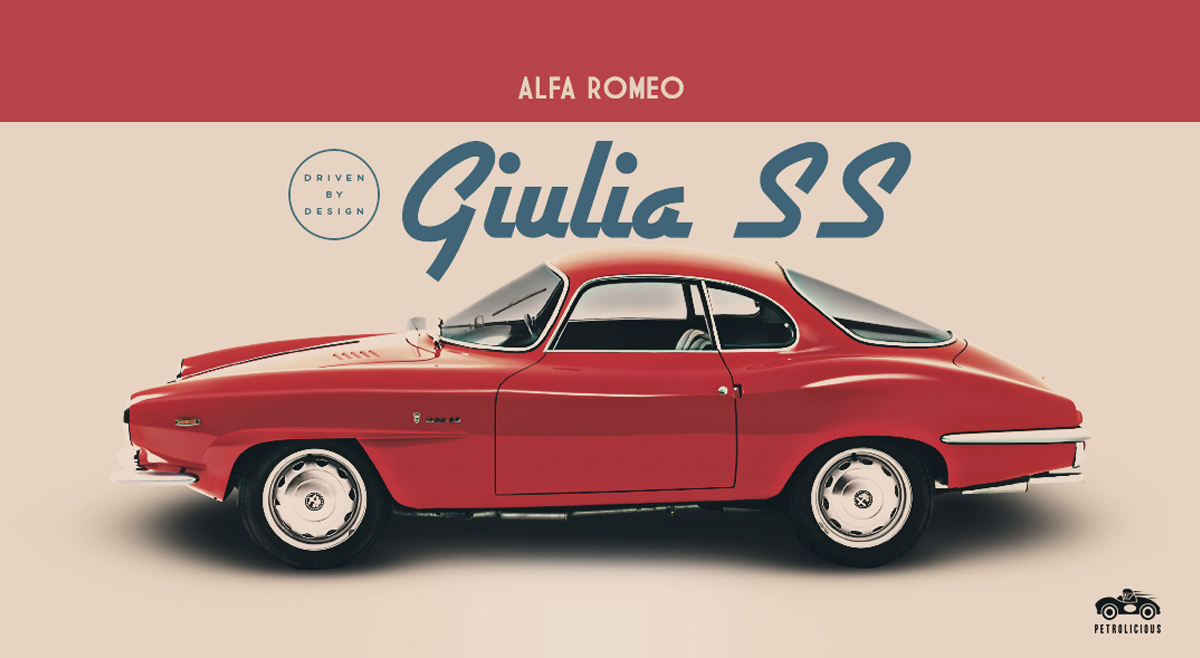

The sexy sixties and Alfa Romeo

Motor’s road testers labelled the Alfa Romeo Giulia SS as a fairly costly thoroughbred of undoubted glamour, but were sure there were always people prepared to pay for qualities invisible to all but the connoisseur. At £2394 the Giulia SS was just £6 cheaper than a Ford Mustang, £100 cheaper than a Lancia Fulvia but £116 dearer than the Porsche 1600SC, and, although Sir Williams Lyons was a special case, a whopping £401 cheaper than an E-Type 4.2.

So, where was the appeal of the Giulia Sprint Speciale? It started with the curvaceous Bertone styling combined with Alfa’s classic cockpit styling, an extremely good five-speed gearbox coupled with a willing twin-overhead-cam motor, with good brakes, good handling (although a bit twitchy in the wet), good performance with 0–100km/h in 10.8 seconds, and comfortable seating.

Triumph reworked the Spitfire, relaunching the popular little ragtop as the MkII. Basically nothing much had changed, but the number of changes and refinements made the MkII a far more effective machine. Over two seconds was sliced off the time to accelerate from rest to 100km/h, and the standing-start quarter-mile took a second less. Two optional extras impressed the testers, first the Dunlop wire wheels, and the other was the overdrive stalk protruding from the right side of the steering column.

Supply of three-litre engines for the new Formula One cars was proving something of a headache. Coventry-Climax showed their impressive FWMW 1.5-litre flat-16 engine, said to develop 220bhp at a fearsome 12,000rpm. It was just one inch longer and 10lbs heavier than the old V8, but though Lotus and Brabham developed a chassis that would take the new engine, they stuck with the old and still-successful V8 design. Despite the interest, Jaguar boss Sir William Lyons hinted that 1966 would see an end to Coventry-Climax Grand Prix engines.

Most potential engine builders were hinting at prices as high as £10,000, so BRM suggested they would make their engine available to other GP teams for £7,000.

Neither Ford of Britain or Ford of America were interested in building a Formula One engine for the new three-litre GP formula.

Those most persistent of optimists, and makers of the most sensational Indianapolis cars, Novi were at it again with a smaller and lighter four-wheel-drive Novi-Ferguson. Andy Granatelli, boss of Studebaker’s subsidiary Paxton Products, believed that the power output from the new car would be a very competitive 595kW at 9400rpm.

March 1990

Making parking easy — four-wheel-steer Honda

It was a strange sensation apparently, road testing a four-wheel-steer car, as the Otago Daily Times tester Graeme Purches found out when testing the Honda Prelude with four-wheel steering. Initially the steering felt far too direct and too skittish when even the smallest movement of the steering wheel caused the car to generate an almost instantaneous repositioning of itself on the road. Turning the steering wheel 13 degrees put the front wheels on nine degrees with the rear one on two degrees in the same direction. You kept turning the steering wheel to the point where the front wheels sat at 18 degrees and then the rear wheels were parallel. When the front wheels were on full lock the rear wheels turned to 18 degrees, but turning the opposite way. This mode was ideal for parallel parking, or turning in tight circles almost within the car’s own length!

For just over $44,000 one got the four-wheel-steer, two-door, 2+2 sports coupé with a smooth two-litre, DOHC, 16-valve, 91kW motor, four-wheel disc brakes, good performance, nice road manners, and quality fit and finish.

Peugeot were planning to return to the racetrack later in the year to compete in Group C of the World Sportscar Championship. Theirs would be the first Group C car to have four-wheel steering, already used on the 405 T16 Pikes Peak Hill Climb cars.

A team of 120 engineers were working on the development of the mid-engined, light-alloy, 3.5-litre V10, intended to pump out 485kW from its 40-valve heads — each with its own DOHC.

Ford’s new drop-top Mazda 323-based Capri had been seen here in limited numbers, the basic version selling at just $32,995 and nicely undercutting the Mazda MX-5 and Peugeot’s delightful 205 cabriolet. Just as it was gaining a foothold, with the basic model looking a very attractive proposition at just $32,995 — about $6000 less than the MX-5 — Ford announced that they were changing over to left-hand-drive production for the rest of the year. So the 101 parts suppliers needed to achieve the Aussie requirement of 70-per-cent local content were going to be fully occupied making bits for the Capri to succeed in the American market.

There were more discussions between Renault and Volvo about forming an alliance to stave off the negative aspects of the Japanese invasion. Peter Gyllenhammar, Volvo’s boss wanted a deal where the two companies shared product development, raw materials supply and parts production. If successful, the alliance would produce over two million cars, 140,000 trucks — 25,000 more than Daimler-Benz — and capture around 20 per cent of the European market. Both companies were in profit, Renault having doubled theirs in 1988, and Volvo netting around $NZ1,160 million in 1989.