Burning desire

The story really begins for me so long ago that I can’t remember when it first became a burning desire to compete in the Mille Miglia, probably one of the most iconic motoring events the world has ever known. The original race was abandoned in 1957 when Count Alfonso de Portago, a Spanish aristocrat driving a Ferrari 335 S, disastrously destroyed himself, his American co-pilot Ed Nelson, nine innocenti, the car, and almost all of the future racing activities of Ferrari, even the sport of motor racing in its entirety. As a result of the Portago accident, Enzo Ferrari was charged with manslaughter, and it was only after four long years of inquest that he was finally acquitted as a case could not be proven.

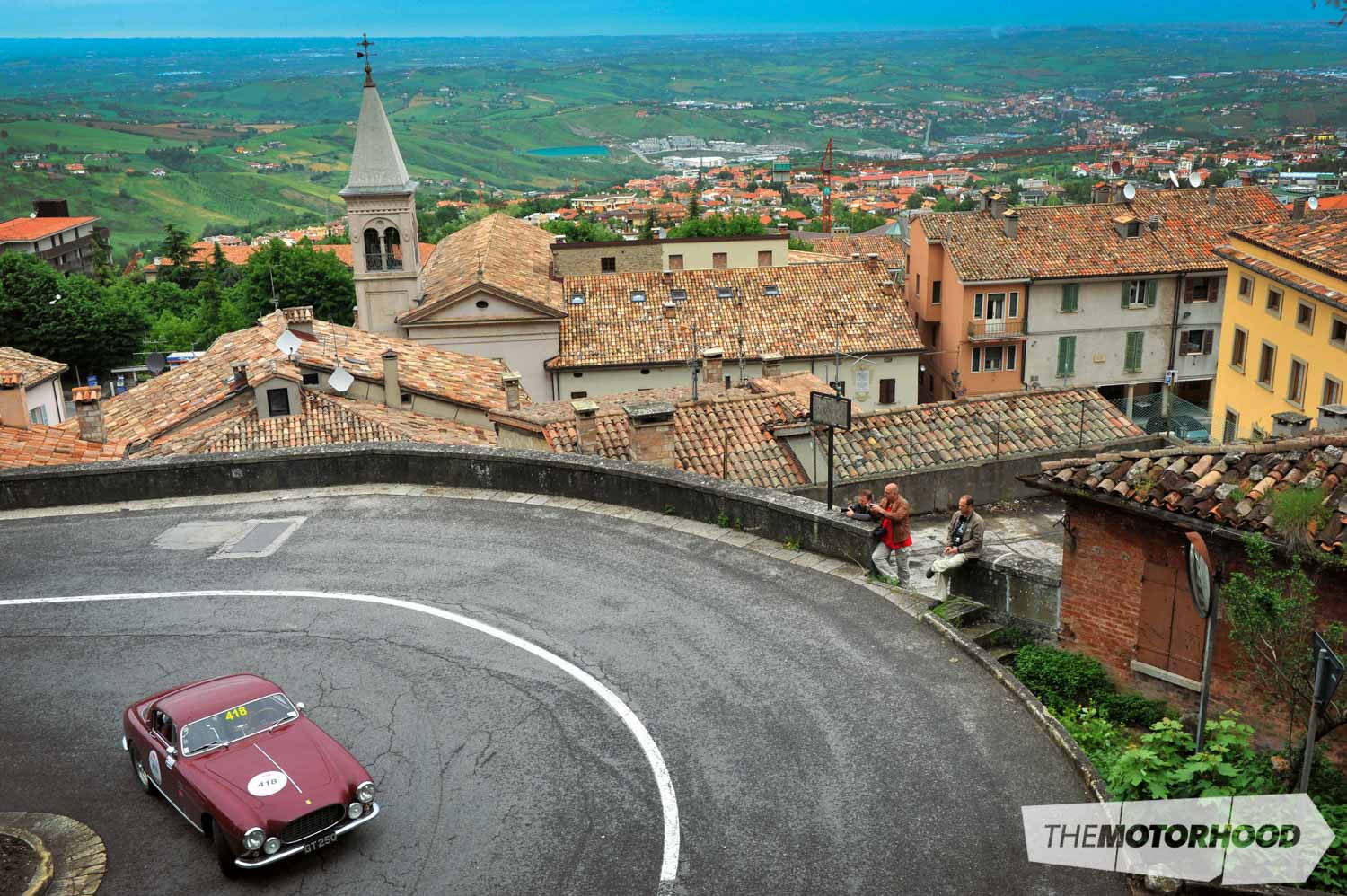

Back to more modern times, and the Mille Miglia Storica was started in 1982 as a watered-down version of the original format, which had seen Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson complete the 1000 miles — at an average speed of just a click under 100mph (160kph) — over the country and village lanes that made up the network of roads starting in the northern Italian town of Brescia, heading south to Roma, and back to Brescia.

Today, the event is not a race as such (well, OK, that is debatable when watching the antics of some of the drivers) but a ‘spirited’ drive that encompasses regularity sections that create a competition of sorts. Some take this regularity aspect seriously, others don’t. We were firmly encamped in the ‘don’t’ category.

Limited entry

The first major step in fulfilling my dream was to acquire a car that was eligible for entry. As only 375 vehicles are accepted each year for the Mille Miglia with, some say, in excess of 1500 entries being applied for, the pressure to find a car with the crucial X-factor is critical, and can very much influence the values of these cars in the world market. This is not to say that all the cars are hugely expensive — some aren’t — but be assured, all the cars accepted for the event are rare or unique.

For the second year in a row, I applied, paying the entry fee up front — which isn’t insignificant — and, like every other applicant, waited three months for the announcement as to whether I was in or not, which was all far too close to the last practical date that the car needed to be shipped to arrive in Europe in good time to be on the starting ramp. You are in a shark pool, trying to swim with the billionaires of the world, and it seems dropping names of known people doesn’t get you anywhere — that is, if you’re a new boy from the sticks, anyway. There are regulars who turn up each year with another special car that proves to be a must-have by the event’s Italian officialdom.

Hunting for a pre-1957 Mille Miglia–eligible car that not only meets the criteria but also spins your own personal wants and desires takes a fair degree of thought and soul-searching. Then, taking the plunge with no real certainty your new steed will get you to the start line makes for nervous chatter — especially on the home front. My affair with Ferrari lead me down that road, and the purchase of the Ferrari Europa GT, but en route I had been hunting for a Lancia Aurelia too — also an eligible car. In the end, I couldn’t resist actually buying an Aurelia as well, sad boy! How do I explain that away? Easy, to Lancia aficionados.

However, I decided to enter the Ferrari, figuring it would be more desirable to the Automobile Club Brescia in that it has had only one or two examples entered in previous years, coupled with the rarity factor (only 35 were ever made), and use the Aurelia as a back-up. As it turned out, eight examples of the Aurelia were successfully entered and only two Europas got the nod — one of which, of course, was my car. Success!

Star search

Scrutineering at the Brixia Expo was not a relaxed affair. After all the months of prepping, yours truly had committed a cardinal sin — I had left all my personal racing documents at home. The blood drained into my boots, rendering me as white as the Pope’s cassock. My medical, as it turned out, wasn’t needed (only for those over 75), nor the visa passport for the car (‘we donta needa sucha thinga’), and, for 30 Euros, I bought a driving licence. The car was not a problema, once the chassis and engine numbers were identified as bona fide. The appropriate sticker was applied and we were in. The colour returned to my face, and the first birra to celebrate didn’t touch the sides.

We weren’t aware at the start, but we were surrounded by stars of Hollywood and the Italian fashion industry. The only noted person that meant anything to us was the pilota driving the legendary, ex–Stirling Moss 300SLR immediately behind us — one David Coulthard. Elsewhere were Roger Penske, safety Formula 1 driver Bernd Mayländer, and, from movie town, Daniel Day-Lewis. Yasmin Le Bon was representing the supermodels while Chris Hoy represented Olympic gold medallists.

Mille Miglia entries were taken from 29 countries, and amongst them were two cars — both Ferraris — from New Zealand.

A lovely acknowledgement was that the organizers kept the car number-24 spot vacant, as that had for many years been filled by the Missonis — of the fashion-house fame — in their Bugatti. Sadly, they lost their lives off the coast of Venezuela in a private plane tragedy in January 2013.

Event highlights

I guess we were under the misapprehension that the event would all be a bit of a doddle; after all, Neil Tolich (my co-driver) and I have done much Targa racing in New Zealand, the US, and Europe, as well as plenty of track races throughout the world. How could a 1000-mile jaunt through Italy be taxing? Well, it came as a bit of shock when day one turned out to last 21 hours, and day two was even longer at 22 hours, while day three was somewhat more leisurely, being only 16 hours. Bed, when we eventually found it, was welcome, but so briefly experienced that, really, we might as well not have bothered.

The weather overall was not good and probably as bad as it gets, certainly when leaving Brescia — the start. The Ferrari’s newly fitted, period-correct Marchal fog lamps were effective, however, the rest of the electrics protested at dedicating all the energy to them. As we needed wipers and the radiator fan working, the Marchals were reduced to being just pretty and expensive ornaments. As we headed south and out from under the influence of the Alps, we struck some better weather, and, on days two and three, Umbria and Tuscany looked wonderful. Pity it was dark for many of the driving hours, though.

A fantastic highlight, which Neil and I decided summed up the fun aspects of the event, was the art of tucking ourselves in behind a little blue and white Fiat Polizia car, with its flashing blue lights parting the oncoming traffic like slicing butter with a hot knife. Running red or orange lights, negiotating roundabouts the wrong way around, going the opposite direction up one-way roads, driving over pedestrian crossings and footpaths — you name it, if there was a unconventional approach, that was our chosen path. Wolfgang, a new chum from Frankfurt, reckoned he had broken more laws in three days than he had in the whole of his life up until this point. It all seemed so acceptable when you were getting the very cool, subtle beckoning ‘come-on’ hand gestures out the window of the cop car. Excellente! We didn’t need to be invited twice — after all, we were driving a part of Italy’s DNA, a 1950s 250 Ferrari!

“Complementi, complementi” was an expression liberally cast our way from event onlookers of all generations. It is said that millions of admirers line the route of the Mille Miglia, and, as the years roll by, it doesn’t appear to have lost any of its magic. You could tell that the compliments were from generous folk jealous of all the participants living the dream they envied. A sense of history the Italians understand and embrace shines through in all they do.

Roma

Late in the evening on day two, the Mille Miglia cavalcade arrived at the outskirts of Rome. After negotiating an atrocious piece of pre-war road coming from the north east, and with my co-driver still suffering from unrelenting jet-lag, we were corralled into groups of 50. Under Polizia escort once again, and with Roma virtually shut down for us, we embarked on a thrilling tour of the hot spots at night — the Vatican, the Pantheon, the Colosseum, the Trevi Fountain, and the Spanish Steps. What a city — what a privilege.

Unfortunately, the only real mechanical/electrical drama we suffered happened just as we pulled into the parc fermé in downtown Rome — a total failure of any generating power. It looked as if we had goosed the dynamo, which had been struggling to keep lights, fans, and wipers running. The next morning, we resolved the issue by buying four new batteries and disconnecting anything that used any power. However, as we discovered after crossing the finishing line the following evening, what had occurred was that a wire had jiggled loose on the regulator — for those with the knowledge and not deprived of sleep, an easy fix.

It seemed to us that every car club and travel agent with a bent for cars had organized a tour group to tag along, join, push, and barge in. There were literally thousands of cars and motorbikes of all descriptions from Aberdeen to Athens intermingling with the Mille cars. The Europeans love their bikes — both push and motor — and they joined in with such gusto it was obvious they were stamping their right to claim the road as well. In particular, the antics on the day three on the Futa Pass, or, more correctly, Passo della Futa, in the province of Florence, would have made the Romans who trudged this way all those moons ago turn in their graves to see the speed at which the moderns negotiated the pass. Busloads of tour groups were parked up with their picnic tents and paraphernalia to watch the spectacle — and if they could give a friendly whack to the cars as they went by, all the better.

The prize-giving ceremony was held in the Teatro Grande opera house. Grand it certainly is, and trophies and cups and flower arrangements lined the full width of the stage. Many trophies to a few seemed to be the outcome, giving us confirmation that the regularity competition was never going to be won by any English-speaking entrant. However, we weren’t there for the trophies but, rather, for the sense of achieving the large prize of accomplishing for ourselves the personal dream of ‘competing’ in the Mille Miglia.

So, a major, excruciating, burning desire in life has been extinguished — well, for the time being, anyway. The Ferrari proved to be not only comfortable to travel in — especially with the newly fitted final drive — but also thoroughly reliable and a crowd-pleaser for sure.

The Mille Miglia is very Italian, and for a first-timer somewhat daunting, but who would want it to be any other way? The Italiano way.

Grazie Mille!