From its debut in 1951, Lancia’s Aurelia Gran Turismo was hailed as one of the world’s finest cars

Older readers may remember New Zealand Classic Car’s irascible columnist, Gabriel — and many will also recall that the late Nigel Roskilly, classic car garagiste as well as a keen Alvis, Daimler, and Jaguar enthusiast, was the man behind the angelic pseudonym. And they will, of course, remember Gabriel’s very clear ideas when it came to determining just what was and what couldn’t be regarded as a classic car.

Indeed, he once wrote, “No-one can tell me a Standard 8, a sidevalve Hillman Minx, a Ford Popular and others of their ilk were classics.”

Immediately following World War II, many auto makers simply dusted off their old, pre-war designs, tarted them up and restarted production.

However, a handful of more forward-thinking manufacturers started to work on developing new concepts based upon the fresh technology that had been developed during the war years. For Gabriel, the cars which resulted from these developments constitute the first that could be truly labelled as classics.

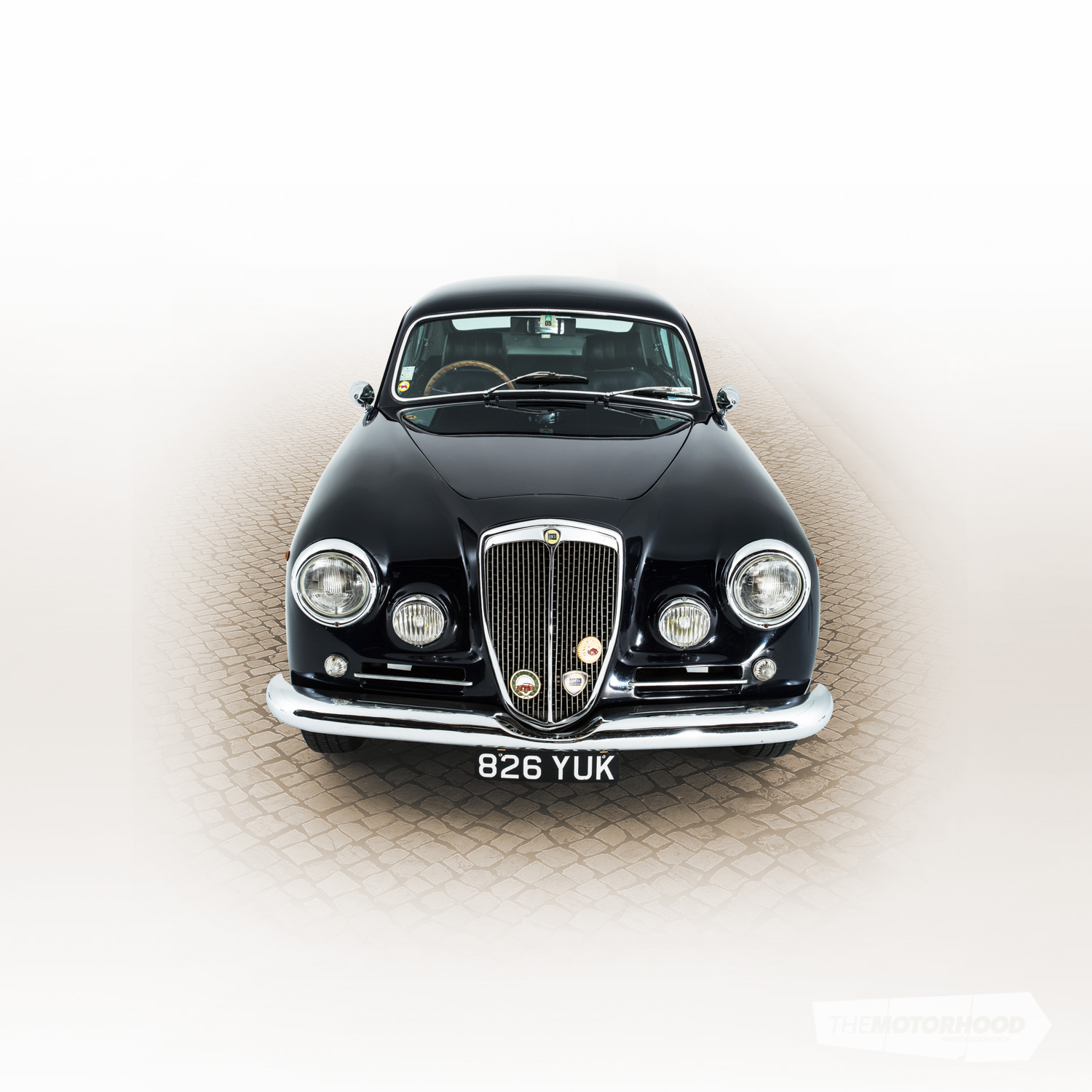

Whereas he poured scorn on what some would term ‘everyday’ or ‘starter’ classics, there is absolutely no doubt that our featured Lancia Aurelia GT would’ve ticked all the boxes as far as Gabriel was concerned. As well as being a gorgeous-looking piece of automotive kit, this Pinin Farina–designed coupé was built by a company with a well-established reputation for engineering excellence and, of course, the Aurelia was certainly no dusted-off pre-war design.

Indeed the company’s founder, Vincenzo Lancia, set down a maxim that would guide his company even beyond his untimely death in 1937 — that maxim being based upon his desire to produce a connoisseurs’ car for the man in the street. As such, in the early days of auto production Vincenzo planned to sell his cars purely on reputation, and there were many who pointed out that his company never allowed mere profitability to spoil a piece of beautiful engineering. Having said that, Lancia was never a slave to tradition, and many of its technical solutions were regarded as being unconventional at the time of their initial introduction.

That statement is worth qualifying with a brief look at Vincenzo Lancia, and his company’s history of engineering excellence and innovation.

Vincenzo Lancia: racer and engineer

Born in Fobello, Italy in 1881 as the son of a wealthy Argentinian, Vincenzo attended technical school at Turin, and soon developed a passion for engineering. Gravitating towards a local bicycle importer, Cierano, he took a post as its bookkeeper. In 1898 Cierano graduated to motor cars, and soon the company gained finance from a consortium of businessmen calling themselves F.I.A.T.

Lancia became one of Fiat’s race drivers, although his full-on driving style meant he didn’t win as many races as his teammate, Felice Nazzaro.

By 1906 Lancia had saved enough prize money to found his own company, although he remained on Fiat’s books as a race driver.

Outwardly, the first Lancia cars appeared conventional, but early innovations included a unique engine oil feed and what we now recognize as being the first twin-choke carburettor. Lancia also broke new ground with the introduction of radially-disposed clutch springs — the type we now see in today’s clutches — and an adjustable steering column. Lancia was also one of the first to fit complete electrical systems to its cars.

However, Lancia’s pioneering engineering didn’t stop there. It was experimenting with V-formation engines as early as 1915, producing V8 and V4 motors before finally introducing the world’s first V6 engine in 1923. Along the way, the Lancia Lambda featured a design in which a torsionally rigid, welded and riveted steel body structure was developed without the need for a conventional chassis. The car was also fitted with a radical independent front suspension system that operated via a sliding pillar with oil dampers, and boasted four-wheel brakes and an engine oil filtration system — all this in 1922!

Following his death in 1937, the company was taken over by Vincenzo’s wife Adele and then their son, Gianni. In 1959 the Lancia family sold the firm to Carlo Pesenti, a cement millionaire. Although the company continued to produce distinctive cars throughout the ’60s, the writing was on the wall, and beautiful engineering could no longer take precedence over profitability. As such, in 1969 the company became part of the giant Fiat combine. From that point onwards Lancias became more conventional in design, although the marque still produced some very desirable cars — including the lovely Fulvia coupé, Dino V6-powered Stratos and, of course, the 037 Rally supercar.

Sadly, Lancia’s international reputation was badly tarnished following a major recall of defective Beta models in 1980. Lancia finally withdrew from the UK market in 1995, only reappearing in 2011 rebadged as Chryslers. Lancia had ended up in bed with Chrysler in the US, the proud Lancia badge even appearing on the American company’s Voyager MPV.

Most recently, Lancia announced its withdrawal from all international markets, Fiat having determined that the famous marque would henceforward only be made available in Italy.

Smitten by an Aurelia GT

Although New Zealand is a long way from Europe and North America’s major classic car fields, there are a few Kiwi enthusiasts with the wherewithal to indulge their passion for classic cars through regular pilgrimages to take part in international events such as the Mille Miglia, Grand Prix de Monaco Historique, Monterey Historics, Tour Auto or the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Paul Halford, the owner of our featured Aurelia GT, is no stranger to these types of international events, having competed in many of them. Most recently, he took part in the historic Mille Miglia at the wheel of his 1955 Ferrari 250 Europa GT (see NZ Classic Car, March 2014).

If you get the chance to quiz Paul with regard to his overseas exploits, you’ll quickly learn that he’s a genuine classic car enthusiast and, as well as the sheer thrill of competing on historic events in a truly desirable classic car, he also very clearly enjoys being in the company of like-minded individuals. That enjoyment, of course, extends to admiration for other enthusiasts’ cars, especially those that are used to compete directly against him on various historic events.

Coming from New Zealand’s much smaller and less diverse classic car scene, European events like the Mille Miglia or Tour Auto give Paul the opportunity to examine first-hand many cars we normally wouldn’t see on our roads. As a country, we can boast of our marvellous cross-section of amazing classic cars, but any visit to an event such as the prestigious European Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este — a top-end car show held annually on the shores of Lake Como, Italy since 1929 — will introduce visitors to truly exotic, multi-million-dollar cars that have never turned a wheel in New Zealand.

As a result, Paul frequently has the opportunity to examine cars most of us will never see in person, and many of these fabulous, blue-chip collectibles are valued well beyond the pockets of a mere millionaire. While Paul may balk at the thought of adding a supercharged Mercedes-Benz 540K roadster, or a genuine Ferrari 250 GTO to his stable (instead, he purchased a superb replica), not all the classic cars he admires while away from our shores have prices that reside in the stratosphere.

Whilst competing abroad Paul soon found himself becoming aware of the Lancia Aurelia GT, not the least when one breezed past him while he was driving his Ferrari Europa GT on an event. At various stopover locations he also noticed the Aurelia drivers tended to group together, and that they presented an interesting, more carefree almost hippie-like demeanour. Despite himself, Paul was attracted to these Bohemian classic car nuts and, of course, the lovely sports coupés they all drove.

It didn’t take long for that attraction to become more concrete, as Paul began to search the worldwide web and overseas motoring magazines for an Aurelia to purchase. Having previously been unsuccessful in entering his Ferrari Europa into the Mille Miglia, an invitation-only event, he rationalized his actions via the thought that an Aurelia might be more readily acceptable by the discerning Mille Miglia organizing committee. However, the truth was much simpler — Paul had now decided he simply had to own one of those charismatic Lancias.

Lancia never built the Aurelia GT in huge numbers, so the international classic car market wasn’t exactly bristling with potential purchases. However, Paul was finally able to track down a dark blue, 1955, series four B20 GT, chassis number B203580, that was offered for sale in Northern Italy. Unable to check the car out himself, Paul arranged for a friend to examine the Aurelia but alas, the car had already been sold. The search continued until, several months later, the Italian car suddenly popped up for sale again — this time from Switzerland. As well, the asking price had jumped up by many thousands of Euros, but this time around Paul would not be denied and, following a thorough inspection and negotiations, the Aurelia GT was his — the car finally arriving in New Zealand towards the latter half of 2013.

Paul says he’s still getting to grips with the Lancia, learning all about its little foibles and vices — as an instance, he quickly discovered that topping up the suspension system’s oil reservoir instantly led to better front-end handling.

Paul is an enthusiast who loves to drive his classic cars on a regular basis — he thinks nothing of motoring his lovely Ferrari 275 GTB/4 from Auckland to Cromwell — and he has no plans for his Aurelia GT to remain locked up in a warm, comfy garage. As Paul puts it himself, the Lancia’s place is on the road, fulfilling its true purpose as the original gran turismo.

The world’s first GT

So, what is it that makes the Lancia Aurelia GT so special, and is it truly the world’s first gran turismo car?

Let’s take a look at the evidence. For a start, the car’s advanced engineering is of real interest. Designed by Vittorio Jano, the man behind some truly iconic pre-war Alfa Romeos, the Aurelia featured a host of innovations. As initially introduced with the B10 saloon, Lancia’s 60-degree all-alloy V6 was the first such engine ever to go into series production. Adding to the equation, the Aurelia’s gearbox and clutch were mounted at the rear, joined to the engine via a two-part propshaft. Oddly enough the gear change was accomplished through a column-mounted lever, although many cars (such as our featured example) were subsequently fitted with a Nardi floor-mounted gear shifter.

While the car’s independent front suspension was by Lancia’s traditional sliding pillars, the combination of semi-trailing arms and coil springs developed for the rear was yet another advance. This did mean, however, that the Aurelia was prone to sudden oversteer when pressed hard — taming this behaviour being inherent in Lancia’s decision to fit a de Dion rear axle set-up on later saloons and GTs.

Further to the Aurelia’s high-end technical specifications, that innovative V6 also provided sparkling performance, and there’s little doubt that Pinin Farina produced a stunning fastback body for the GT.

Finally, for those who believe competition prowess is a prerequisite for any genuine classic car, it pays to know that Giovanni Bracco and Umberto Maglioli drove a virtually standard Aurelia GT to second place overall in the 1951 Mille Miglia, being beaten only by Gigi Villoresi’s significantly more powerful Ferrari. Subsequently, Aurelias performed well in many major sports car events, notching up creditable finishes at Le Mans and on the gruelling Carrera Panamericana. Felice Bonetto, driving an Aurelia GT, also scored a famous outright victory at the 1952 Targa Florio. Privateer Aurelia racer, Johnny Claes, won the 1953 Liége-Rome-Liége, while Louis Chiron drove his Aurelia to first place at his home event, the Monte Carlo Rally, in 1954.

The Aurelia’s successful motor sport appearances also led to the car being chosen by many experienced race drivers. Juan Manuel Fangio, Mike Hawthorn and Jean Behra all used Aurelia GTs as their own personal cars. Rather less fortunately, Mike Hawthorn’s father died at the wheel of his Aurelia GT.

The equation seems almost too perfect — advanced engineering, superb style, class-leading performance, celebrity owners and an indisputable competition pedigree. It was a heady mix, and an expensive one — the Aurelia GT was always a pricey car to buy. As an example, in 1954 the Lancia was listed in the UK at a staggering £3472. To put that into context, a Jaguar D-Type could be bought at that time for a mere £2685!

Lancia, never a company to sit on its laurels for too long, continued to develop and further refine the Aurelia, improving performance, handling and comfort over a period of years.

However, above all it is those two initials ‘G’ and ‘T’ that define this truly special Lancia. While there had undoubtedly been cars which could be classed as being a GT, or gran turismo, well before the Aurelia’s appearance, Lancia was the first to append GT to a production car’s name. By combining the Aurelia’s undoubted merits with a GT badge, Lancia set the benchmark for what we now recognize as a genuine gran turismo car. It was a winning concept which was taken up by virtually every other motor manufacturer worldwide, and today a GT badge can be seen affixed to a huge variety of vehicles. Alas, very few of these modern GTs could ever hope to match the Lancia Aurelia GT for sheer style and charisma. Even fewer would even come close to challenging the Aurelia GT’s undoubted milestone design status.

1955 Lancia Aurelia GT B20 Series 4

- Engine: 60-degree V6

- Capacity: 2451cc

- Bore/stroke: 78x85mm

- Valves: Pushrod ohv

- Comp ratio: 8:1

- Fuel system: Twin Weber 40 double twin-choke

- Max power: 88kW at 5000rpm

- Max torque: 183Nm at 3500rpm

- Transmission: Four-speed manual

- Suspension F/R: Sliding pillar/de Dion rear axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs

- Steering: Worm and sector

- Brakes F/R: Drum/drum

Dimensions

- Overall length: 4370mm

- Width: 1550mm

- Wheelbase: 2650mm

- Kerb weight: 1220kg

Performance

- Max speed: 180kph

- 0–100kph: 12.2 seconds

- Standing ¼ mile: 19.1 seconds