data-animation-override>

“Kevin Shaw takes a look at how New Zealand’s oldest dedicated drag strip came to be, and gives thanks to those who made it all happen”

A bit like the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, the Pukekohe Hot Rod Club (PHRC) team had forged ahead with the new track, believing that “if you build it, they will come”. Well, after a few years of hard work, the track was ready — now all they needed was for the people to come. The official opening was set for Easter Monday, 1973, and with perfect weather over the weekend, the final shakedowns were held by the strip workers and a few competitors to work out the procedures for the new drag strip. Unfortunately, opening day was to go down in history for all the wrong reasons, with Monday dawning overcast and the weather only getting worse as the day went on.

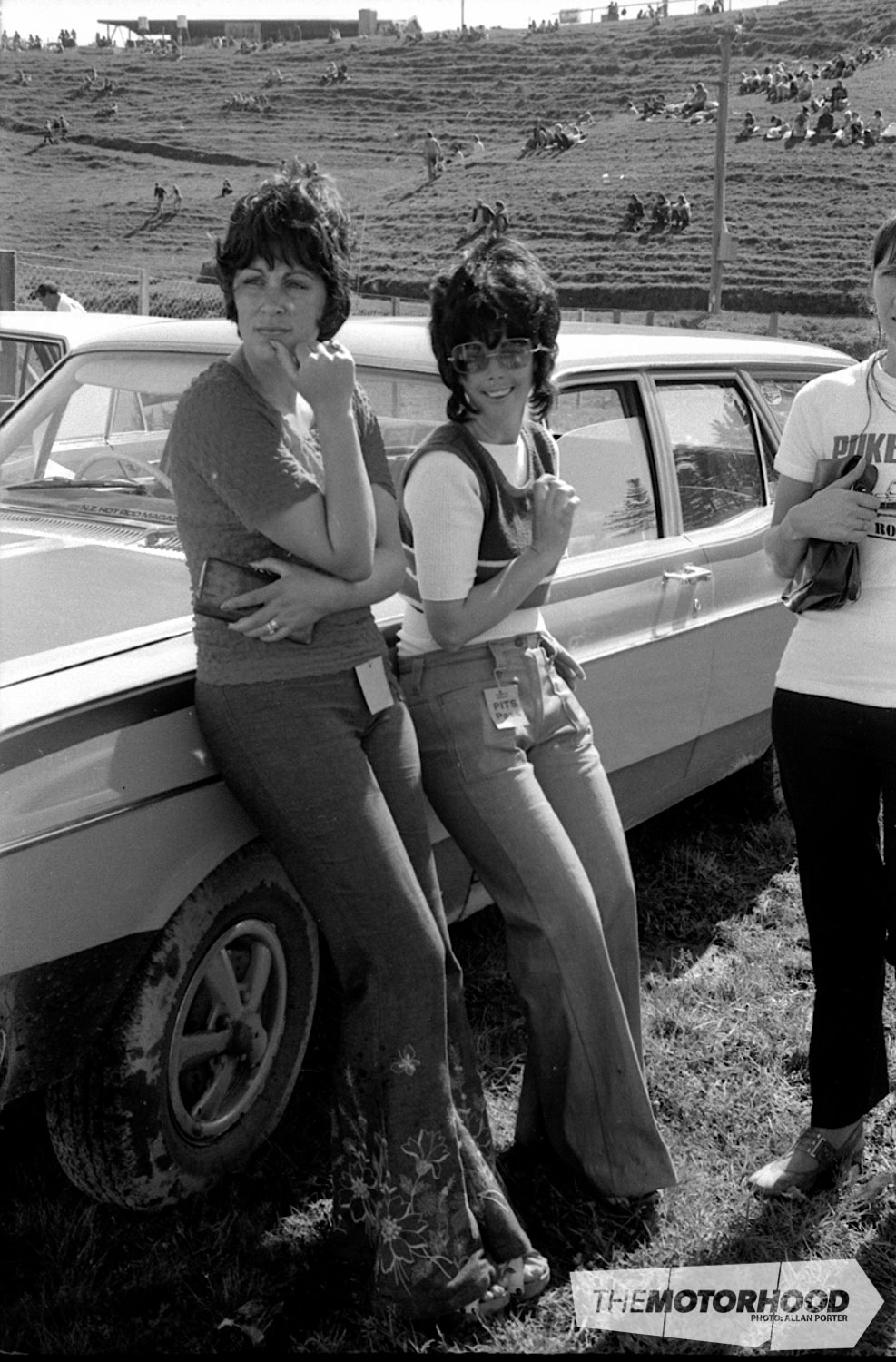

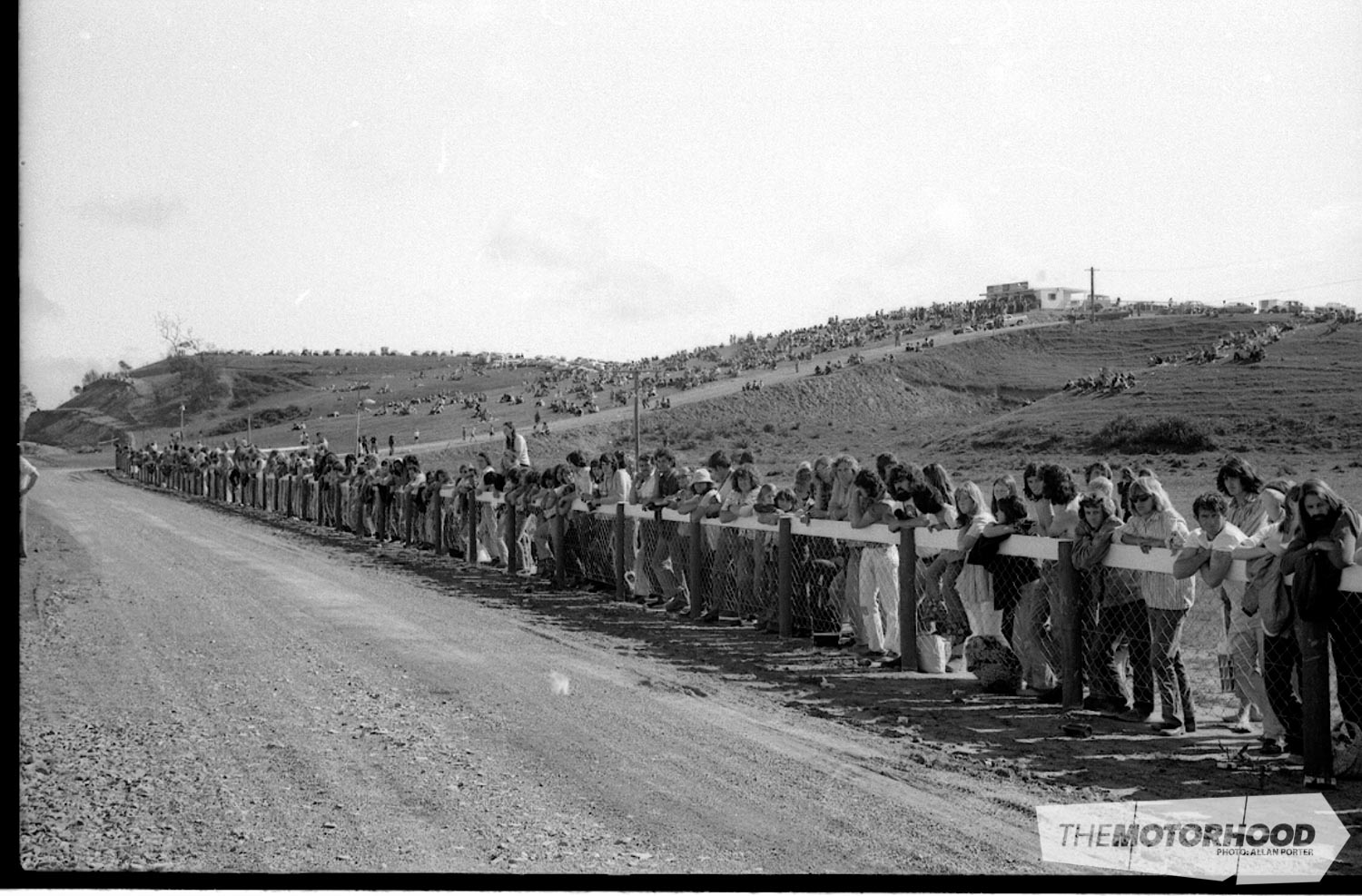

With all of the promotion for the opening meet, the forecast for inclement weather did nothing to keep away the crowds. Before long there were 8000 people waiting at the strip, and many thousands more stranded on SH1 with the queue of vehicles stretched all the way back to the bottom of the Bombay Hills. At the track, the fans were all eager for some racing, but the weather had other plans and the heavens opened up. As a bit of entertainment, the huge convoy of hot rods that had cruised over from the Easter show at Mt Maunganui formed a procession down the drag strip in the pouring rain. The parade made for an impressive sight and proved that hot rodders never give up! At 10am the strip was dry enough for a few street cars to lay down some qualifying passes, and a couple of comp cars tried their luck too, but an hour later the rain set in again and with the track conditions too dangerous for anyone to race, the meeting was over. The meeting may have been cancelled, but the huge public turnout made the national news that night, where the rescheduled opening date was announced.

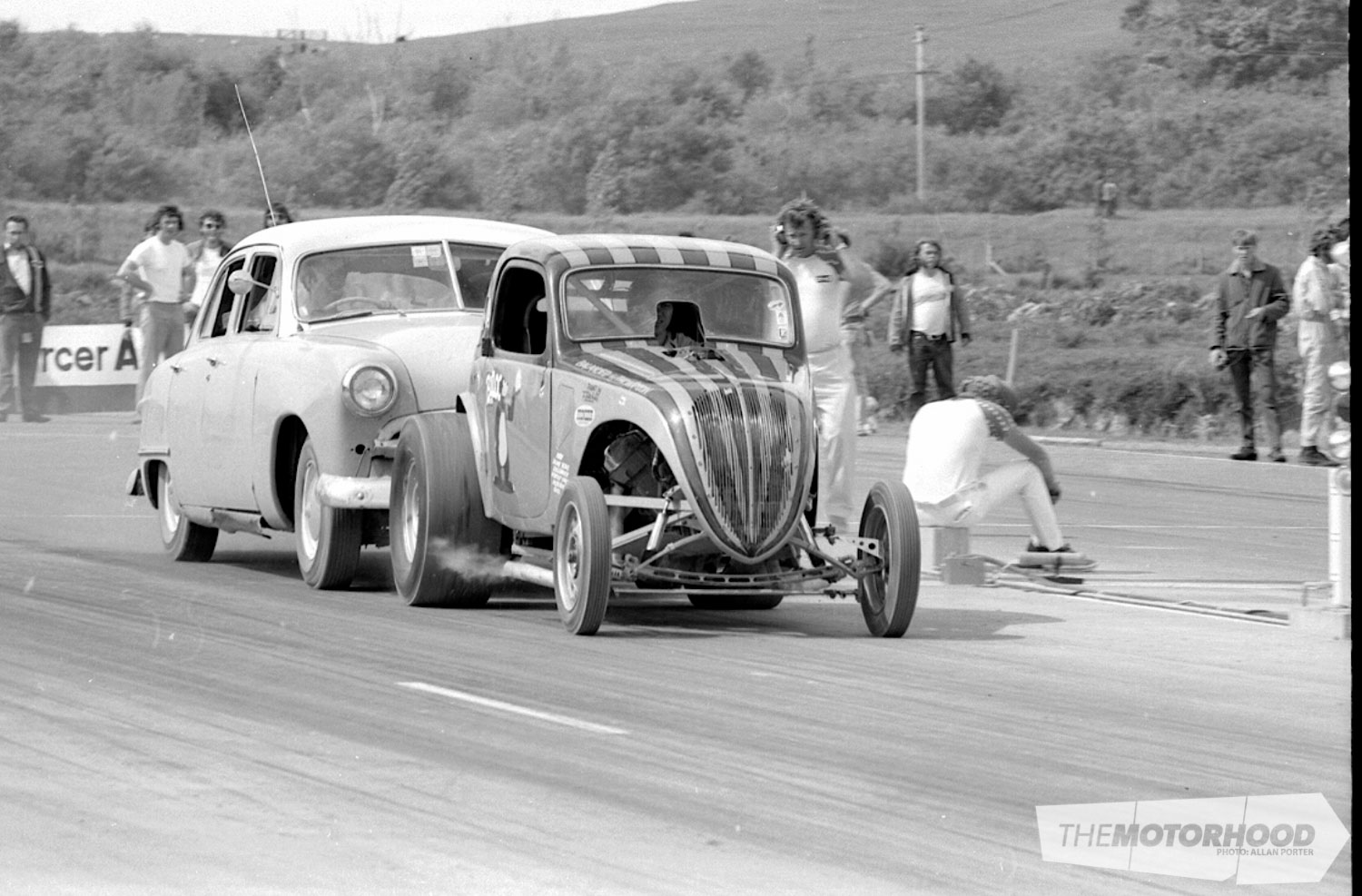

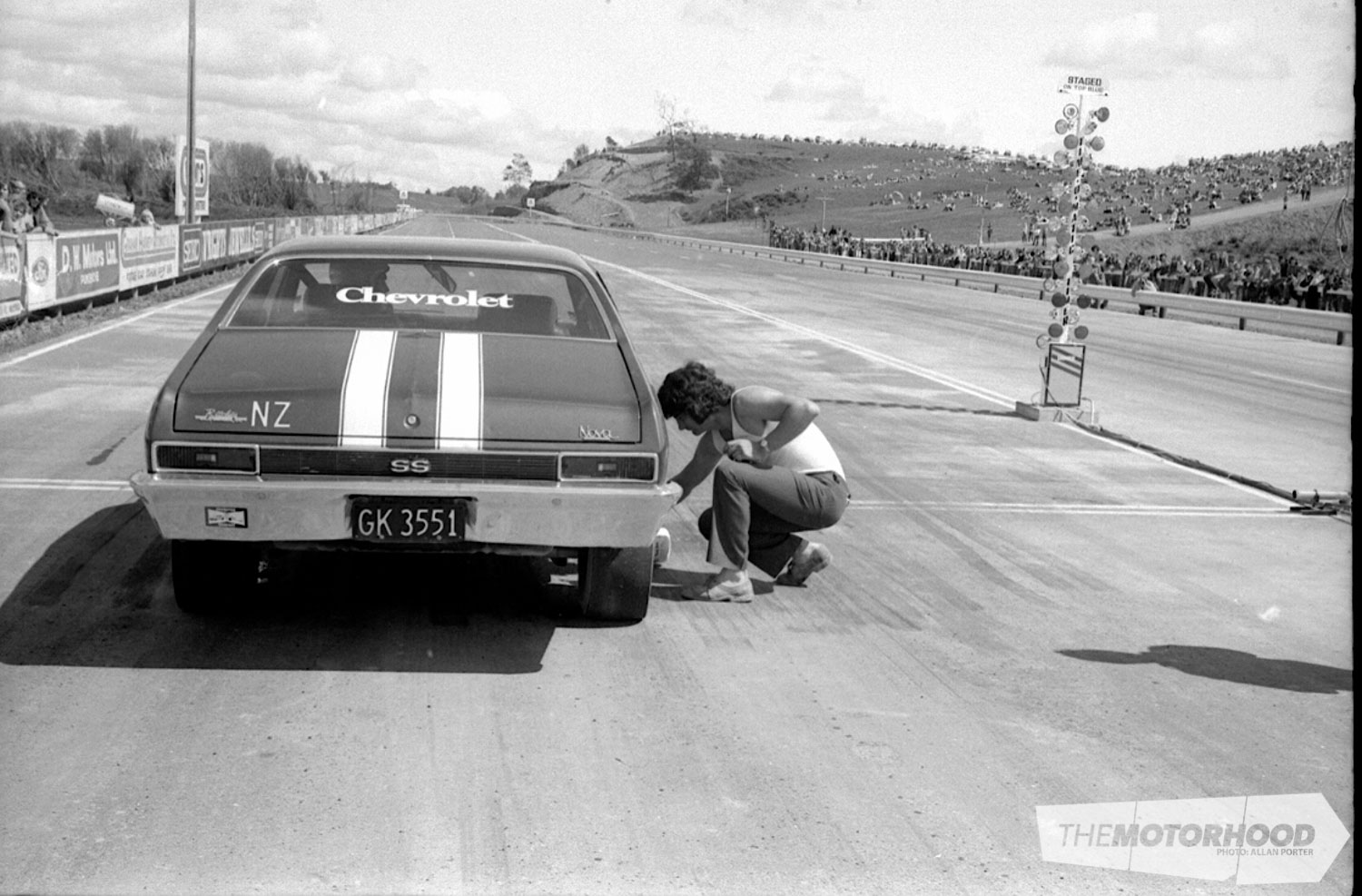

Sunday May 6 dawned kinder, and although there were a few showers, the new track was finally used in anger. Peter Lodge started on the path to being one of New Zealand’s all-time racing heroes by laying down a stunning 10.9 at 137mph, but Robin Unkovich was the star of the day running his blown dragster to a best of 10.1 at 139mph! The crowd present were finally treated to real drag racing on a proper track here in New Zealand! Thanks to the hard work of all involved, the transition from Kopuku (via the closed road in Wiri) to an international A-grade track was complete. The opening meeting had been run, and despite the false start, it had been a huge success and showed the potential of the venue. Now it was time to plan the way forward.

Thanks largely to the efforts of the PHRC, the future was looking bright for drag racing in New Zealand. The new facility had raised the profile of both New Zealand hot rodding and drag racing on the international stage, with recognition from hot rod associations in America, Australia and Britain. Probably just as importantly, there was recognition from MANZ here in New Zealand too, with hot rodding and drag racing entering a new age as a motorsport that was to be taken seriously (and it had almost become respectable). The NZHRA even received an invitation from the NHRA to send our top car to the 1973 drag racing world finals in Amarillo, Texas, which they had to decline due to the lack of a truly competitive car by US standards.

Over the winter of ’73 more plans were laid to set the strip up for the years ahead. Louie Antonievich’s infamous Dodge Fargo bus had served as the timing tower and communications centre for the opening meeting, but was obviously inadequate for the job long-term. In yet another example of the community getting behind the track, PHRC member Henry Van De Broek and his father John, who ran a building business in Pukekohe, came to the track’s rescue. They offered to build the two-storey timing tower — with help from the PHRC members — to provide room for all of the track staff to run the timing gear, PA, etc., with lockable storage below, and it could be paid off as the club could afford it … interest free! Forty years later, the tower is still there; a tribute to John and Henry Van De Broek, and to the people from the local community who had no vested interest in the drag strip or sport, yet were prepared to get in and help the club to get this track running.

The PHRC realized that some overseas racers would make good drawcards, to bring in the crowds and help make the first season a success. The track needed to get money back in the coffers and repay its debts, so they looked across the Tasman for some willing racers. Kiwis had been travelling to Australia and the States for years, watching and learning from the racers there, and of course bringing back plenty of go-fast bits for their own cars. On one of the trips to the Chesterfield Nationals in Australia, some of the PHRC members met up with Dave Gale who raced a rapid 302-powered Model A, and Wally Pushkey with his infamous drag bike, both of whom were keen to come and race at the new track at Meremere.

Once again support came from the local community — including George Yearbury, father of now well known drag racer Wayne, and a few other Pukekohe businesses — to cover the cost of the freight, airfares and accommodation. These racers also worked with the local drivers, assisting them to prep and tune their vehicles. The racing and tuning experience of the Australians was proving invaluable, as evidenced at subsequent meetings, with local racers getting consistently faster and some getting close to the times being run by the Australians back home!

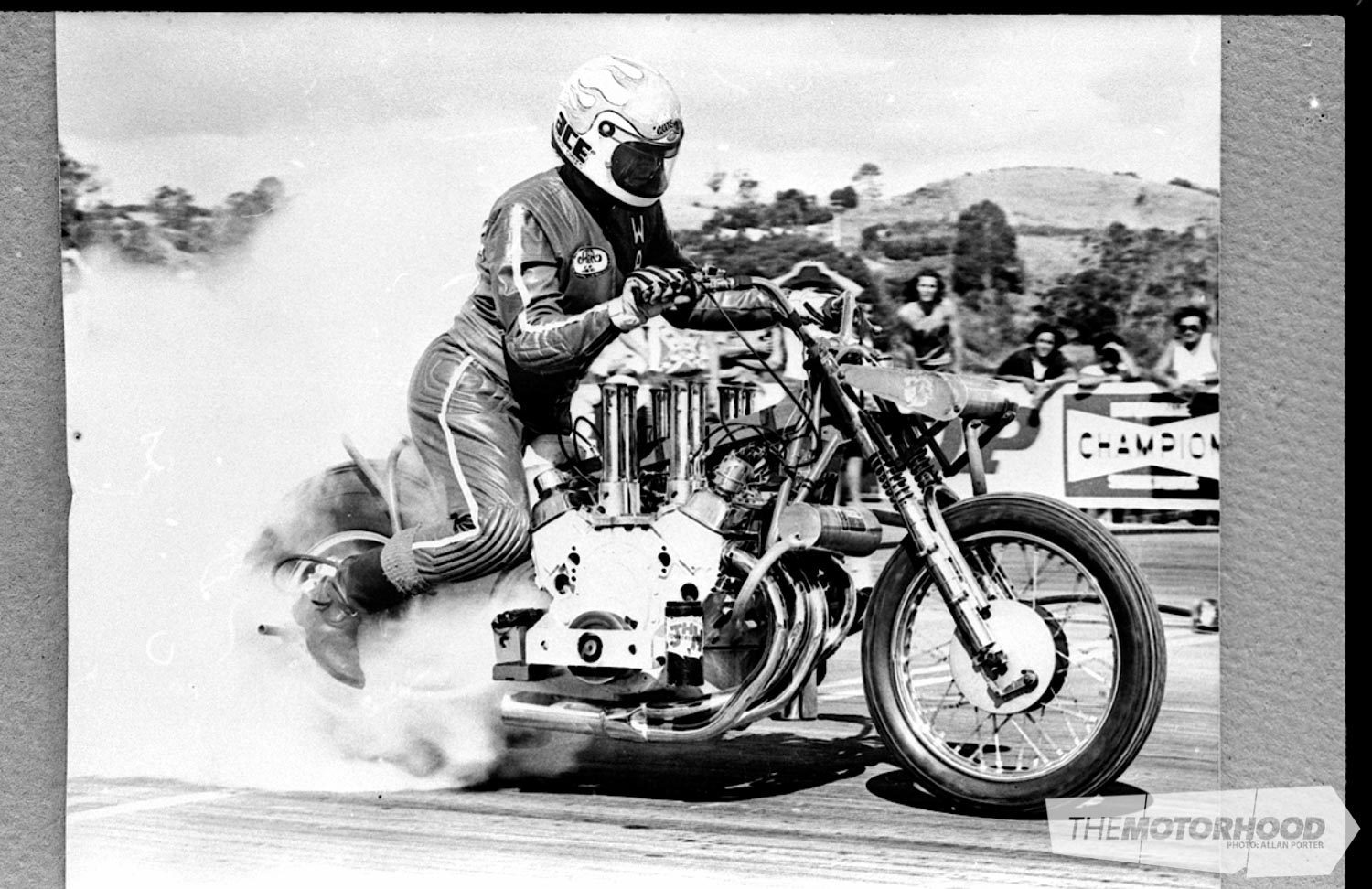

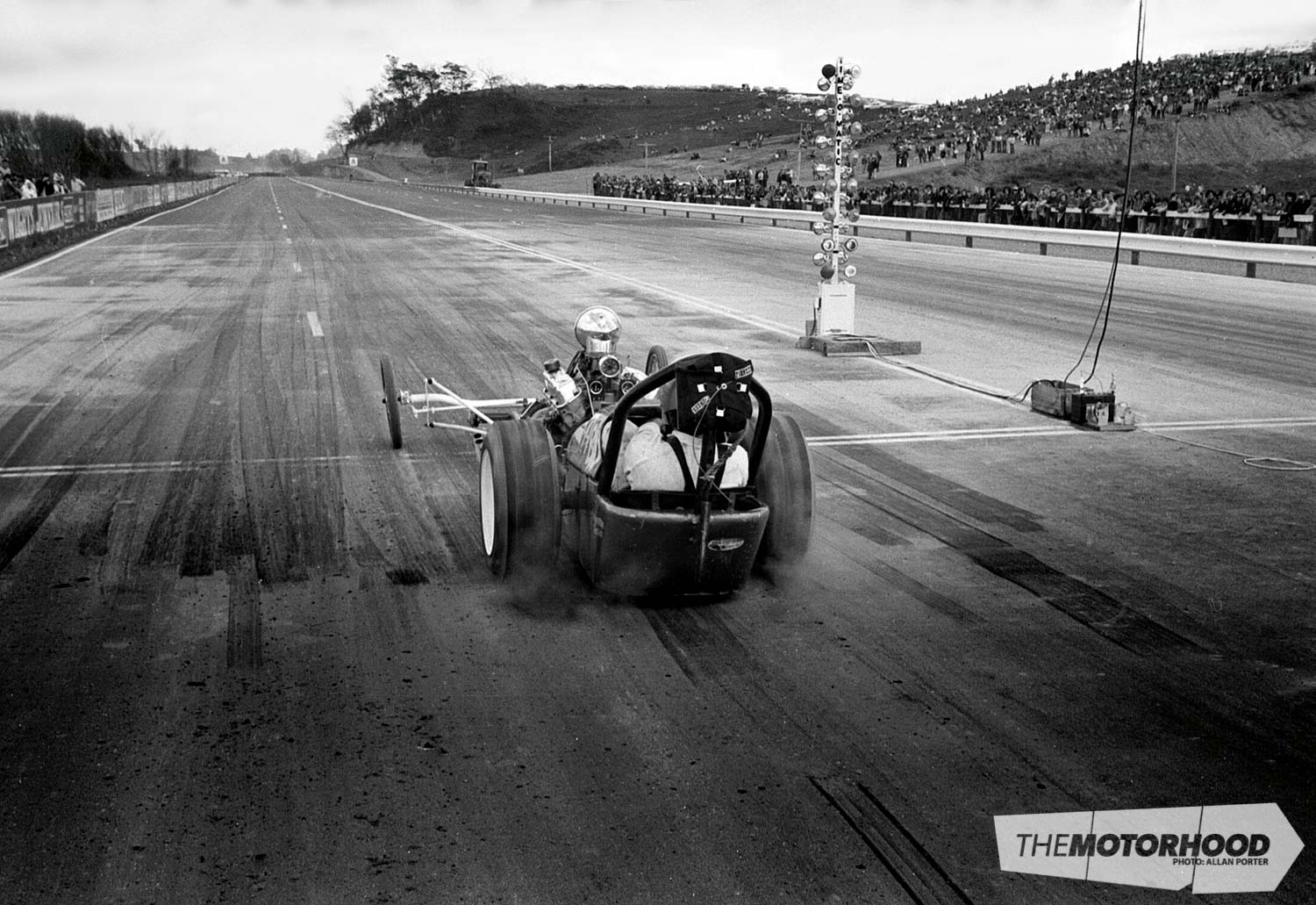

Probably the most spectacular display put on over the ’73–’74 season would have been Brisbane’s Wally Pushkey and his injected 350 Chev-powered drag bike. With no clutch and direct drive giving around 2.9:1 gearing, he would set the bike on a stand and start it up. Then he’d bring the revs up until the back tyre was doing about 120mph, and kick it off the stand while hanging on for dear life! Wally’s first pass in New Zealand was a wild one: smokey and sideways for the first 50 metres or so before straightening it up for a stunning 11.1 at 137mph. No one-shot-wonder, Wally backed this up with a 10.9 at 131mph, then a very sideways 11.1 at 138mph, and finishing with a 10.9 at 127mph. I don’t know what would possess someone to try something like this as it would takes a lot of guts and skill to even contemplate it! But Wally was happy being here in New Zealand doing it for us, and in later years he’d return again.

With a new track and exciting racing, there were new sponsorship opportunities — and not just for the local businesses that had helped with the building of the strip. Champion Spark Plugs (who would later become naming rights sponsor), Coca Cola and BNZ had been with the project since inception, along with the many local businesses that continued to pour money into the venue in return for advertising. Much of the advertising would not be allowed in today’s politically correct world, but in the seventies the programmes sold at the track could proudly advertise Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes and “Lion Beer — Breakfast of Champions”. Back then it was all fair game, to help put money in the coffers to repay loans, and promote and develop the track.

One important piece of sponsorship for the ’73–’74 season was Kensington Carpets announcing they would promote a ‘Mr Drag Racer’ award, based on a points score series across the season. Rather than just concentrating on winning a meeting, racers would need to compete against every other racer, in every other class, to place consistently across the season, in order to get a shot at the $500 prize money. If you were in contention, you had to keep your car running and keep turning up to race. Breakages that would normally see a car parked until next year were fixed or at least patched up to run at the next meeting.

The inaugural Mr Drag Racer award from the ’73–’74 was won by Ken Vincent narrowly beating Gary Taylor by just one point! Ken Vincent, forty years later is still competing, and is racing at a nostalgia meet in Australia as I write this. In subsequent years, many of the Kensington Carpets’ Mr Drag Racers have become New Zealand drag racing legends, with drivers like Alan Lim who narrowly beat Nick Leifting in ’74–’75 or Ivan Jujnovich who overtook Alan Lim at the final meeting of the ’75–’76 season for the series win. Other winners include Mike Gearing, Wayne Yearbury, Errol Uttinger, Brett Wilson and Garth Hogan, all of whom have contributed majorly to the sport over the years.

The ’74–’75 season saw more Aussies brought over to entertain the crowds at Champion Dragway, beginning with Smokey Joe Cook and his outrageous drag bike. First spotted by a group of PHRC members at the ’73 Australian Nationals in Adelaide, they knew he was a must-see for the crowds back home. Smokey Joe was the first in Australia to do 130, 140 and then 150mph, and the first bike rider into the nine-second bracket. The bike itself was powered by a VW flat-four stroked to 1900cc and ran on an 80-per-cent nitro mix to achieve its 180hp. With no gearbox and just a clutch with a direct drive to the rear wheel, the M&H slick would be lost in tyre smoke — and often sideways — for the first two-thirds of the strip.

February 1975 saw more Australians, with Bill Croft in his injected big block altered running consistent low nines, and Jim Walton in this blown Hemi T-altered blowing everyone away running low eights! In Australia these racers received appearance money in addition to any prize money, but they ran for free at Champion Dragway. The PHRC and sponsors covered the freight and travel costs, along with their running costs here in New Zealand, and of course they also received a good old Kiwi holiday. The effect the Aussies had on drag racing here was huge, they drew huge crowds to Champion Dragway, and their vast knowledge of racing and tuning was eagerly absorbed by the local racers.

Virtually all of the monies raised from these meetings were poured back into the sport, from repaying debt to completing facilities at the track or building new amenities to support it. It was all about building and growing the sport, and providing the best possible facility for the racers. About this time the PHRC began running drag racing tours of the US, where racers could learn more about getting down the track quicker and faster, and of course it was the best opportunity to bring home the right equipment. No doubt there were a few raised eyebrows at Customs when a traveller returned with a tunnel ram and a set of BBC Venolia pistons in his suitcase. These trips provided the racers with large increases in knowledge, and with the appropriate parts on-board, the Kiwi cars improved rapidly. There was no doubting that drag racing was here to stay.

These early ’70s meetings set the benchmark for racing in the years ahead; it really was the beginning of a golden age for drag racing in New Zealand, despite the impending worldwide fuel crisis and other problems of the era. It’s hard to look back now to the times of carless days, no petrol sales on weekends and race tracks closed to help save fuel, and yet during this tough period for motorsport, Champion Dragway was born, and it’s managed to survive and thrive. With the resurfacing work that has just been completed along with the other improvements, the old Meremere track will hopefully be here for decades to come!

Our thanks to Ralph Wright for all of his assistance with writing this article, and Allan Porter for the photos.