Regular New Zealand Classic Car columnist Donn Anderson has won this year’s MotorSport New Zealand Feature Journalist of the Year award with his ‘Jack Brabham: a motor-racing legend’ article published in our July, 2014 issue.

Read the full story here:

Donn Anderson remembers a great Australian sportsman who had a soft spot for New Zealanders

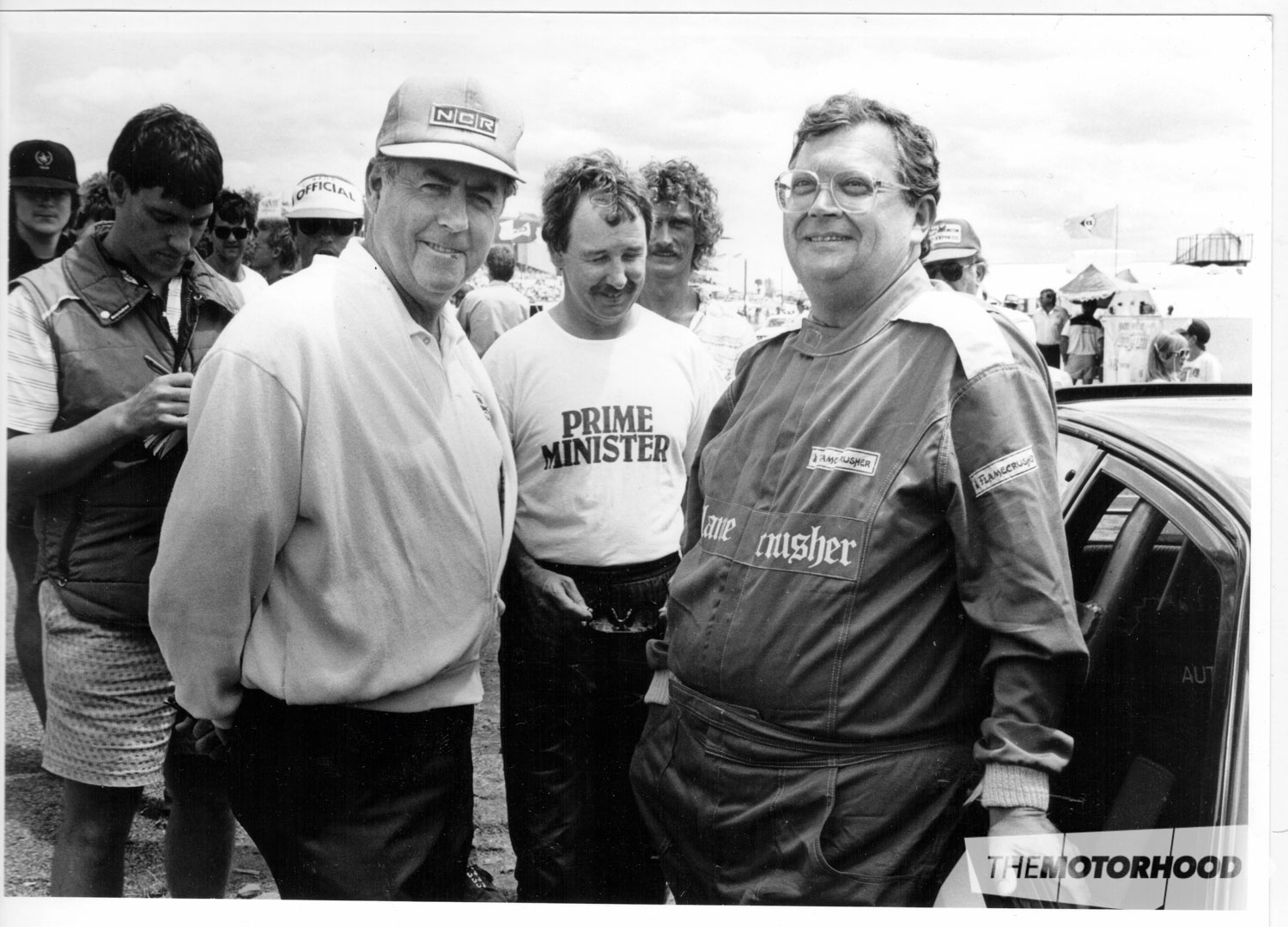

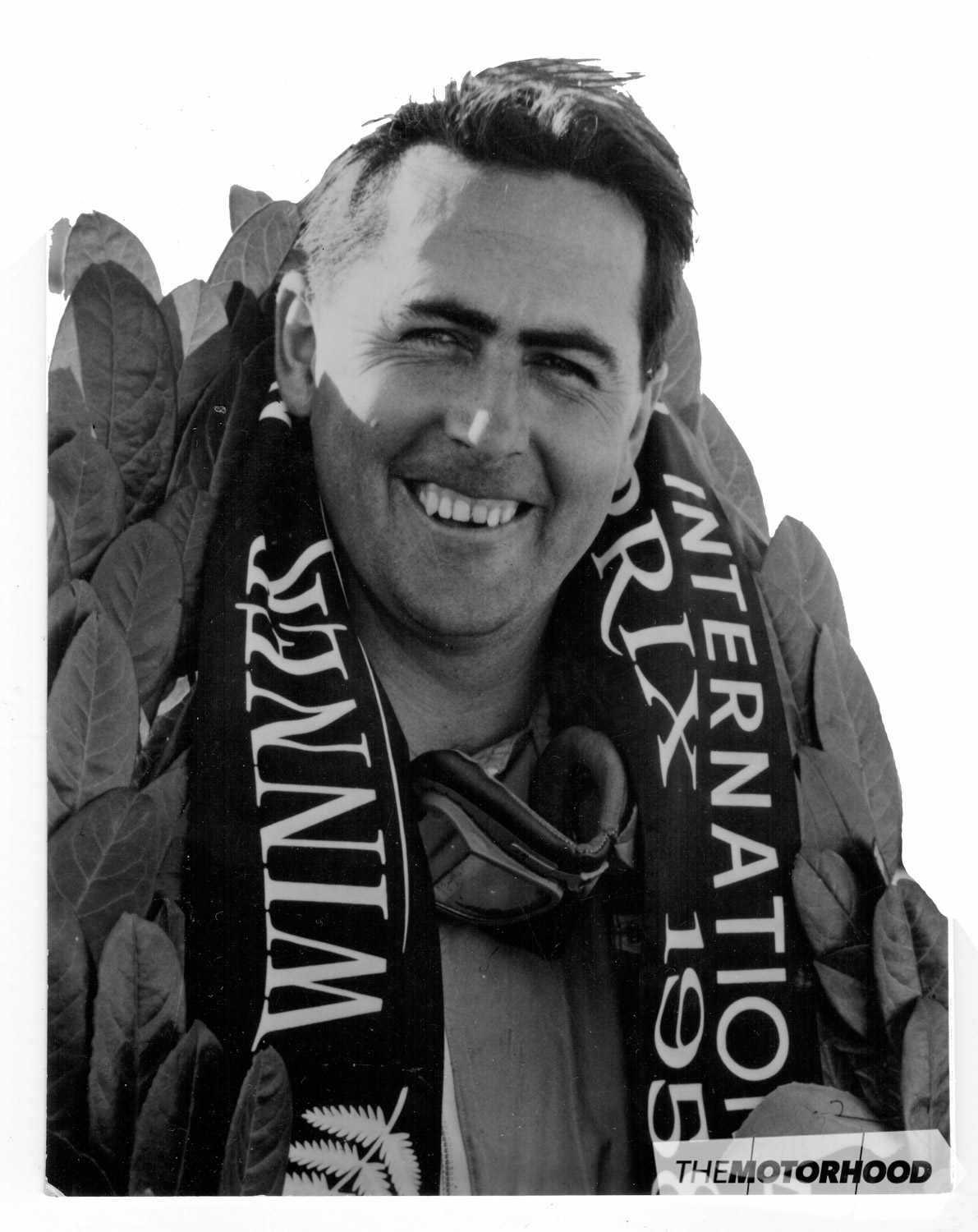

Few New Zealanders appreciate Sir Jack Brabham’s influence on the standing of local motor racing, both domestically and internationally, over the past 60 years. Right from the inaugural New Zealand Grand Prix at Ardmore in 1954, the wily Australian was an evergreen supporter of this country’s premier race, winning that event on three occasions.

More than this, however, the native Australian had a real affinity with New Zealanders, and was a major driving force behind a young Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme. Without Jack Brabham there would almost certainly have been no McLaren Formula 1 team, or a world driver champion in Hulme.

Despite health problems, Jack was thinking about plans for his 90th birthday not long before he sadly passed away at the age of 88, in the early hours of May 19 at his Queensland home. His death was sudden and unexpected, coming just nine days after the 55th anniversary of his victory in the Monaco Grand Prix, his first F1 success. Only a few days before Brabham’s passing, Phil Kerr had been talking to the quiet champion on the phone, and he said he was feeling great.

Affectionately called ‘Black Jack’ because of his pre-shave stubble, Brabham’s all-round ability as a superb racing driver, engineer and business made him a legend in his own time. Against stiff competition that included Tony Gaze, Peter Whitehead and Horace Gould, Jack finished sixth in the 1954 NZIGP driving a Cooper-Bristol, and he reckoned he would have done better but for a blown head gasket.

Critical career point

Bruce McLaren and Phil Kerr were two teenagers with a desire to go motor racing, and when Brabham based his race car at Les ‘Pop’ McLaren’s service station in Remuera in 1954, the boys were soon doing odd jobs for the visiting Aussie. They got to know him even better the following summer, when Jack finished fourth at the Ardmore airfield circuit.

That time in Auckland marked a critical point in Brabham’s career. “When I went over to New Zealand with the Cooper-Bristol in January 1955 for the Grand Prix, the idea of coming to England wasn’t foremost in my mind,” he said years later. “But it was while I was there that I listened — once again fascinated — to the stories told of motor racing in Europe.”

Jack couldn’t expand his small engineering business, as it was in a residential area of Sydney, and he reckoned officialdom was almost killing the sport in Australia. By the time the Ardmore weekend was over, Brabham had decided to go to England for one racing season. He’d purchased a Cooper-Bristol two years earlier after its first owner committed suicide while the machine was en route to Australia. Later Brabham would regret not taking that car to Britain, as the Cooper-Alta he negotiated to buy on arrival from Peter Whitehead turned out to be rather tired.

However, he had taken the first step to Europe, had his early meetings with John Cooper, and was on the path to world championship success.

Bruce McLaren’s dad had purchased a couple of race cars from Brabham, and the McLaren residence became Jack’s second home when he visited Auckland each summer. Kerr, who went on to first manage Brabham and then the McLaren racing team, recalls how Jack was “unbelievably helpful to Bruce”, and ultimately persuaded John Cooper to admit the young Aucklander into the Formula 1 works team.

Winning combination

Brabham was also hugely supportive of Denny Hulme. Fellow Australian business partner Ron Tauranac, who co-founded Motor Racing Developments and the Brabham team in 1962 with Jack, wanted a fellow countryman to join the F1 team, but Jack overrode this and Hulme won the seat.

“Jack was often talking about retiring and having Dan Gurney and Denny as the two Brabham drivers,” Kerr said. “However, Gurney left at the end of the 1965 season, and with it lost his chance to be world champion. Jack, of course, stayed on driving with Denny.”

Hulme remembered this as the opportunity of a lifetime, but much of the credit also goes to Phil Kerr for negotiating Denny into the Brabham team that won him the 1967 world drivers’ championship. When Hulme was at the point of abandoning European racing and returning home, Phil gave him a job on the shop floor at Brabham in 1962, in what became a critical foot in the door. Aussie Gavin Youl broke a collarbone, and his F2 Brabham was taken over by Hulme, who promptly put the car on pole at a Crystal Palace meeting in London. This performance was enough to convince Jack that Denny was worthy of a works drive.

McLaren drove a Formula 2 Cooper during the 1958 season, and when he returned to England the following year Kerr made the same journey to become Jack’s secretary and manager.

“I was very tempted to go over in 1958 to have a look around, but I waited,” Kerr said. “As things turned out, Bruce heard that Jack was looking for someone to handle his business affairs, and when he came out early the following year for the Australasian events he spoke to me about it.”

It was the beginning of a happy association that lasted nine years, until Phil joined McLaren in February 1968. Initially, and unsurprisingly, Jack wasn’t happy about the parting of company to the opposition by both Phil and Denny, yet there was no long-term animosity.

Formula 1

Rewind to nine years earlier, and Bruce and Phil shared a little bedsitting room in Surbiton, and their daily menu was nothing if not modest. When they were home, the high point of the week was a Sunday roast at the Brabham household.

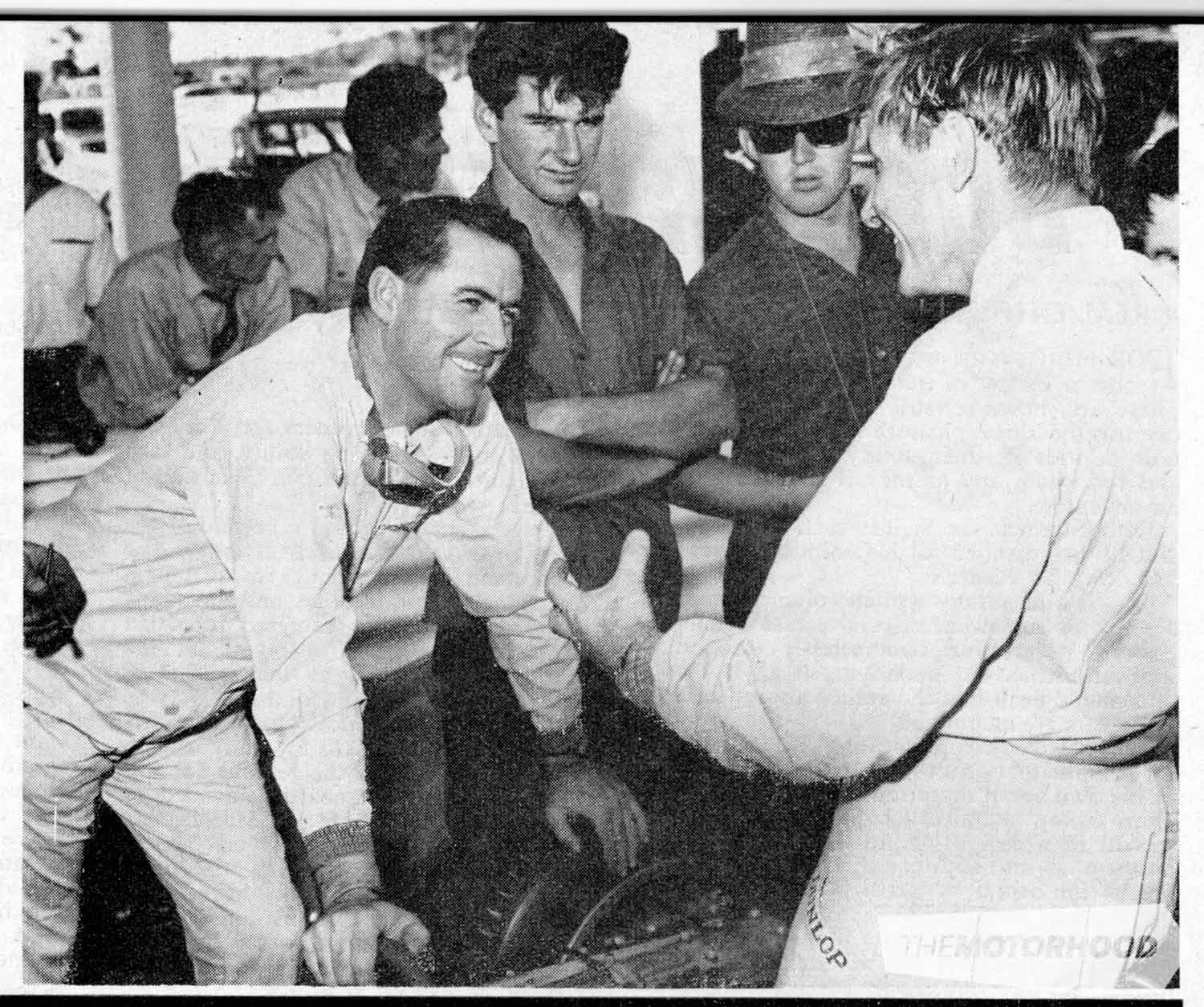

Kerr recalls driving to the south of France with McLaren in his Morris Minor, acquired from Jack’s first wife Betty, for the 1959 Monaco Grand Prix that marked Bruce’s first Formula 1 drive with Cooper. Bruce finished fifth, while Jack secured the first F1 win for the Cooper works team. Both Brabham and McLaren had incredible feel for a car, while also recognizing the ability and sheer brilliance of a small minority of drivers.

Midway through the 1959 season, Kerr remarked to Brabham that he had a good chance of becoming world champion.

“There are two words that might prevent me — Stirling and Moss,” said Jack.

He recalled thundering flat-chat through Stowe corner at Silverstone when Moss came sailing by on the outside, and even had time to throw Brabham a wave. In fact, the Australian went on to take two successive world championship titles for Cooper in 1959 and 1960.

Working within an expanding Brabham organization in the early ’60s, Kerr coped with a multitude of tasks each working day, including the hassle of negotiating starting money and grappling with contracts. Jack was always prepared to do a lot on his own, and face overwhelming odds.

“I never knew Brabham to consider that anything was impossible,” Kerr said.

Testing, selling, and converting cars

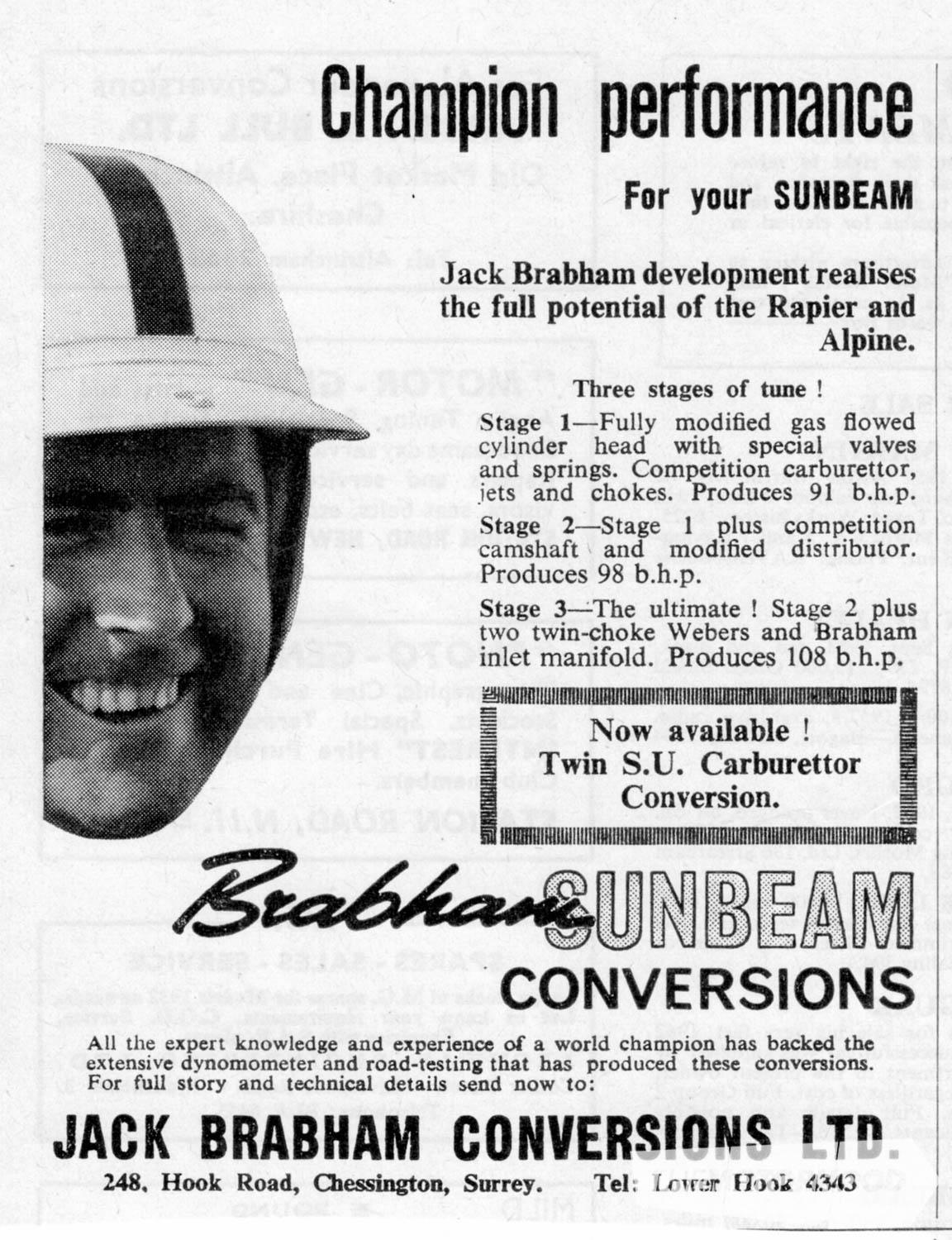

With Jack becoming a household name, little wonder he was asked to write road reports for major British newspapers. These were ghostwritten, but Brabham was still expected to drive the test cars and relay his findings to the journalist. Jack’s problem was finding enough time to sample the press cars that were arriving thick and fast at the factory.

Kerr recalls the famous E-Type roadster, registration 77RW, delivered by Jaguar to be tested. Jack suggested Bruce and Phil sample the E-Type, and McLaren subsequently acquired one for himself as a road car. Jack was keen to test the unique suspension on a road-test Citroën DS19, and proceeded to drive up and down the kerbs in suburban Surrey on the way to a Cooper factory visit with Phil Kerr.

Brabham also secured the franchise to sell Rootes Group and Standard Triumphs, and regularly appeared in advertising for the Sunbeam Alpine. In the early days he used a two-door Borgward sedan as his drive car, before choosing a BMW 2000 and a Sunbeam Rapier. A sub-agency for BMC cars was secured, but Brabham decided he didn’t want to follow the trend of converting Ford and BMC products. He had acquired a garage and service station in Chessington, Surrey, in 1959, a year before Tauranac arrived from Australia to join Jack as a racing car designer for their company, Motor Racing Developments.

Brabham expanded into the conversion business, removing the engines from new Triumph Heralds, and replacing them with 1220cc Coventry Climax FWE motors that produced around 82kW. In an 18-month period, 90 Herald-Climax saloons were built, and the same power unit was used to repower a few MG Midgets and Austin-Healey Sprites.

Since Climax engines were used in the all-conquering rear-engined F1 Coopers, Jack was able to secure a friendly price on the FWE units for the Heralds. One of his four companies also produced conversion kits for 800 Sunbeam Rapiers and Alpines, and built three engines for the works Alpines that ran at Le Mans in 1962.

Motoring milestones

When Jack finished fourth in the 1962 United States Grand Prix, he became the first driver ever to score world championship points in a car of his own design. Many milestones followed and, by 1967, Brabham was building more single-seater racing cars than any other constructor in the world, while also supplying tuning kits for the Vauxhall Viva to 26 GM plants worldwide.

When I visited John Cooper’s Honda dealership at Worthing in southern England in 1993, he told me the original idea for a ‘Cooperized’ version of the Mini had not come from himself, but from Jack and Bruce.

Jack could see the attraction of sports production models like the Mini Cooper and Lotus Cortina, and Vauxhall liked the idea of a Brabham Viva, but could not work the expected relatively low production volume within its plant. They approved the conversion kits that were first applied to the HA series Viva, and then the HB model that launched in 1966. By this time Vauxhall agreed the Brabham Viva should be a regular listed model — the kits were fitted by dealers.

Yet through all this came the racing, and a man with a great sense of humour. In 1966, at the grand old age of 40, Jack arrived on the grid at the Dutch GP wearing a long beard he had bought from a local party shop, and hobbling along with a floor jack from the pits acting as a walking stick. The crowd and the media loved it.

A true legend

Brabham had a major scare at Indianapolis, and suffered a big testing accident at Silverstone. In the 1959 Portuguese Grand Prix, a local back-marker swung across in front of him as he was lapping the slower car. The Cooper mounted straw bales and headed straight towards a telegraph pole.

Jack recalled: “There was a dreadful crunching noise as the car hit the pole, and I really thought I’d cooked my goose.”

He was thrown from the car, bounced on a straw bale, and ended up right in the middle of the track where he was almost run over by teammate, Masten Gregory. Miraculously, Brabham escaped with minor injuries in contrast to a bizarre incident at a Goodwood Festival of Speed meeting many years later while in retirement.

He was returning downhill after an exhibition run in the hill-climb section when the Brabham open-wheeler ground to a halt. The car was being towed back to the pits when the tow cable broke the rollover bar, and struck Jack on the back of the head. It took a long time for the brain injury to be diagnosed, and the injury was troubling in his final years.

I was a budding young schoolboy with a primitive motoring magazine in January 1959 when I visited Jack and Bruce in the back yard at the McLaren family home in Remuera. It was the measure of both drivers that they stopped work on their Coopers to chat about their racing prospects, while encouraging my modest publishing efforts. Jack went to the trouble of locating, and signing a photo for me. Two days later they finished second and third in the Grand Prix behind Stirling Moss, and the pair were first and second in two successive years. Brabham took part in every New Zealand Grand Prix from 1954 until 1964, delighting Kiwis with his often spectacular, but always controlled style that belied his geniality and modesty. And as an engineer, Jack was usually kind to his machinery, a factor he considered was reflected in his success.

So many achievements from a man who was a good friend to New Zealand. Three times world champion, the first (and still the only driver) to win an F1 title in a car of his own manufacture, and the first racing driver to be knighted. A true legend no less — and a good bloke into the bargain.