data-animation-override>

“Everyone knows what a Shelby Cobra is — but how many know about one Kiwi and his role in the development of this iconic machine”

Original Cobras now command eye-watering sums, even though they proved troublesome to sell when new — indeed, many original Cobras were initially bought as competition vehicles and, like all such cars, were tossed aside when, inevitably, they became uncompetitive. Not to mention the complications brought about by disagreements concerning who owned the rights to the Cobra’s design and overall concept — or even the ‘Cobra’ name itself.

Long after the original Cobra had become part of motoring history, the car’s muddy lineage was still making itself known, as disputes over who should take the credit, who owned the rights to build so-called original reproductions, and who owned the right to name their cars ‘Cobra’ continue right up to the present day.

Hand built

From the start, Cobras have always been hand built — meaning that each example was a little different — right from the very first car built by Carroll Shelby at his speed shop in Venice, California. That initial Cobra utilized a British AC Ace body fitted with Ford’s new 221ci V8, a BorgWarner T10 gearbox, and four-wheel disc brakes. From the outside, the only differences between the Ace and Shelby’s creation were squared-off wheel-arch extensions to accommodate the car’s wider track and, much to AC’s disgust, the removal of all the British car-maker’s badges and their replacement with Shelby Cobra items. However, before limited production even began, the car’s V8 had been enlarged to 260ci.

At this stage, Shelby may only have had one car actually built but, seeking publicity, he offered his new Cobra to Road & Track and Sports Car Graphic magazines. They recorded its explosive performance — 0–60mph in a mere four seconds and a standing quarter time of 13.8 seconds.

The Shelby Cobra had truly arrived and would soon become a permanent fixture on US race tracks. With the express desire to beat rivals such as Ferrari and Chevrolet’s Corvette, Shelby and Pete Brock (not to be confused with the late Peter Brock of Aussie racing fame) further developed the Cobra, adding a roll-over bar, those iconic Halibrand alloy wheels, larger rear wheel-arch extensions, and air scoops. And, of course, the Ford V8 engine grew in size and was soon up to a capacity of 289ci.

Due to the simple fact that Shelby was building Cobras with racing in mind, FIA homologation was a major requirement — and this led to the so-called FIA Cobra. These homologated cars displayed quite a few differences from the ‘standard’ Cobra — the doors had wheel-arch cut-outs, with larger wheel arches front and rear, plus an extra inlet in the lower part of the front valance. However, the most notable alteration was the addition of a swage line in the boot lid. This peculiarity was there to allow the Cobra to carry an FIA-approved suitcase in its boot!

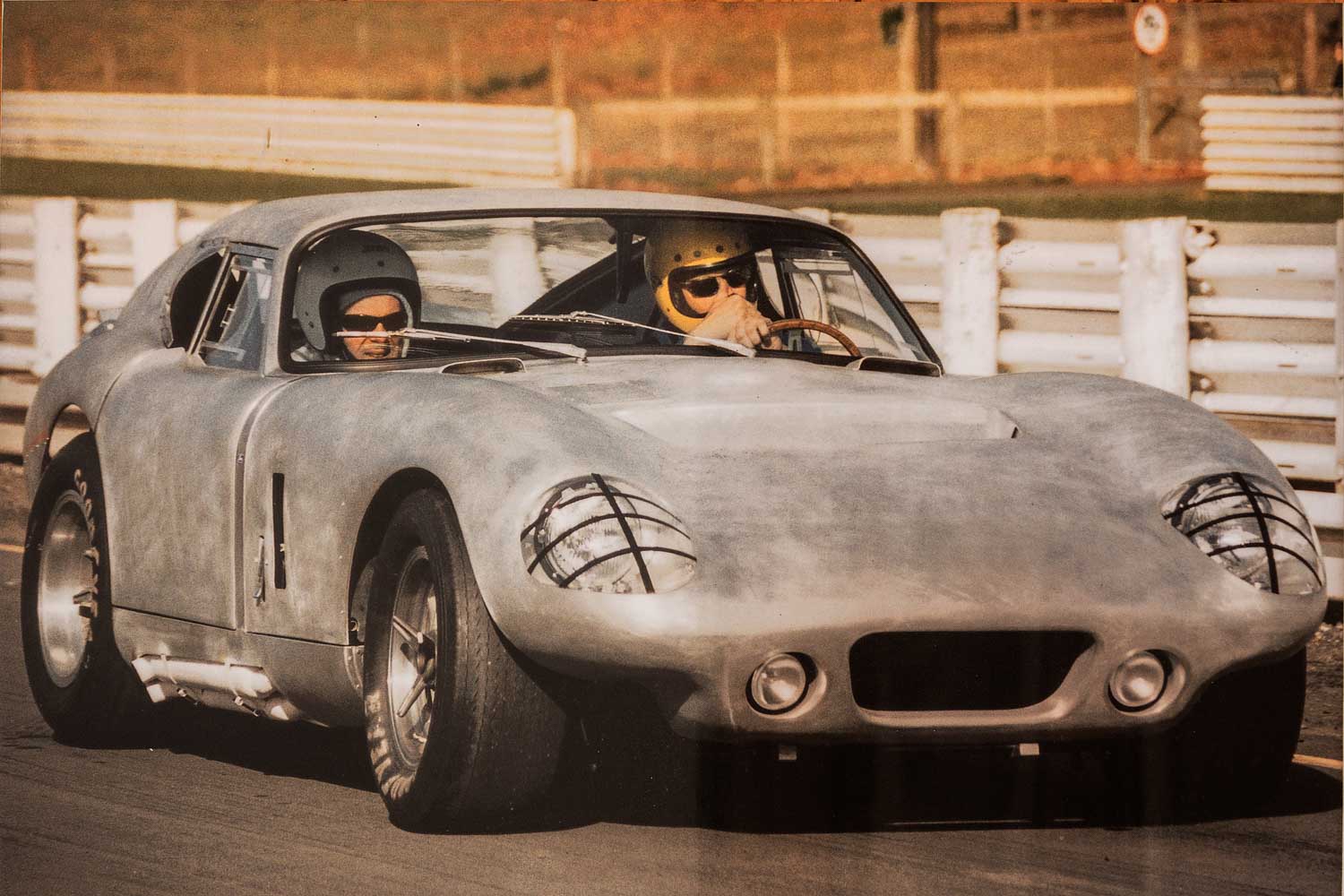

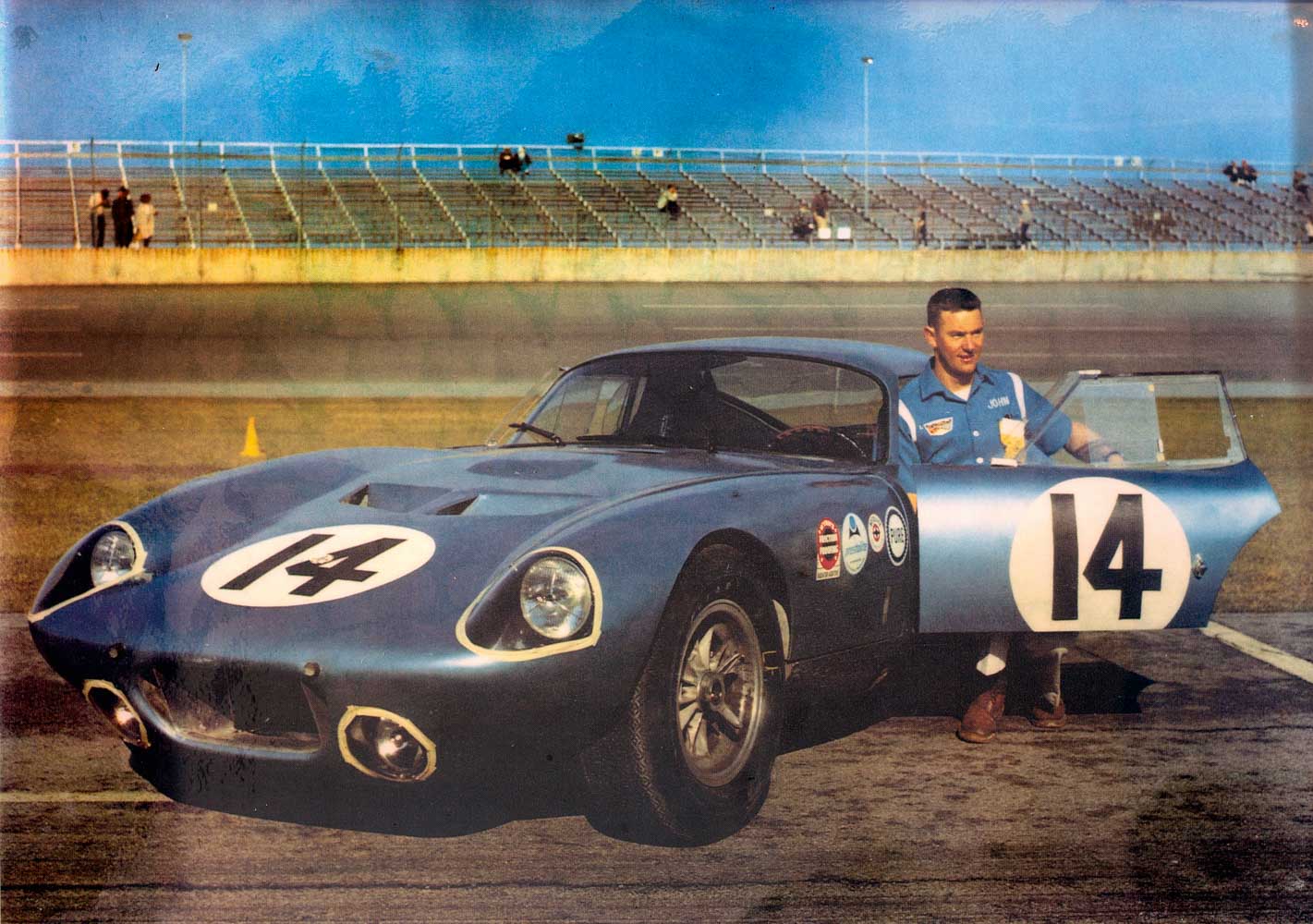

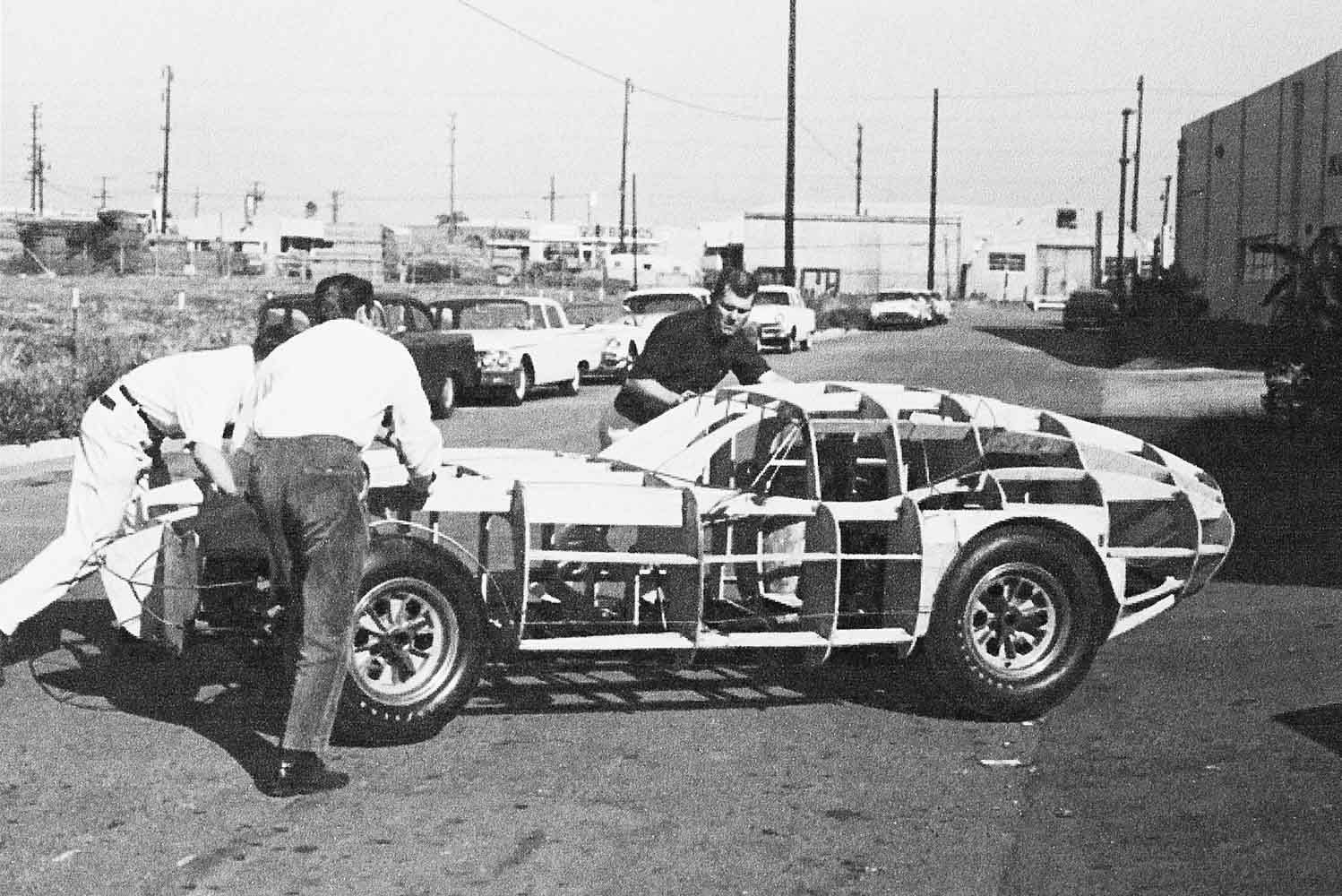

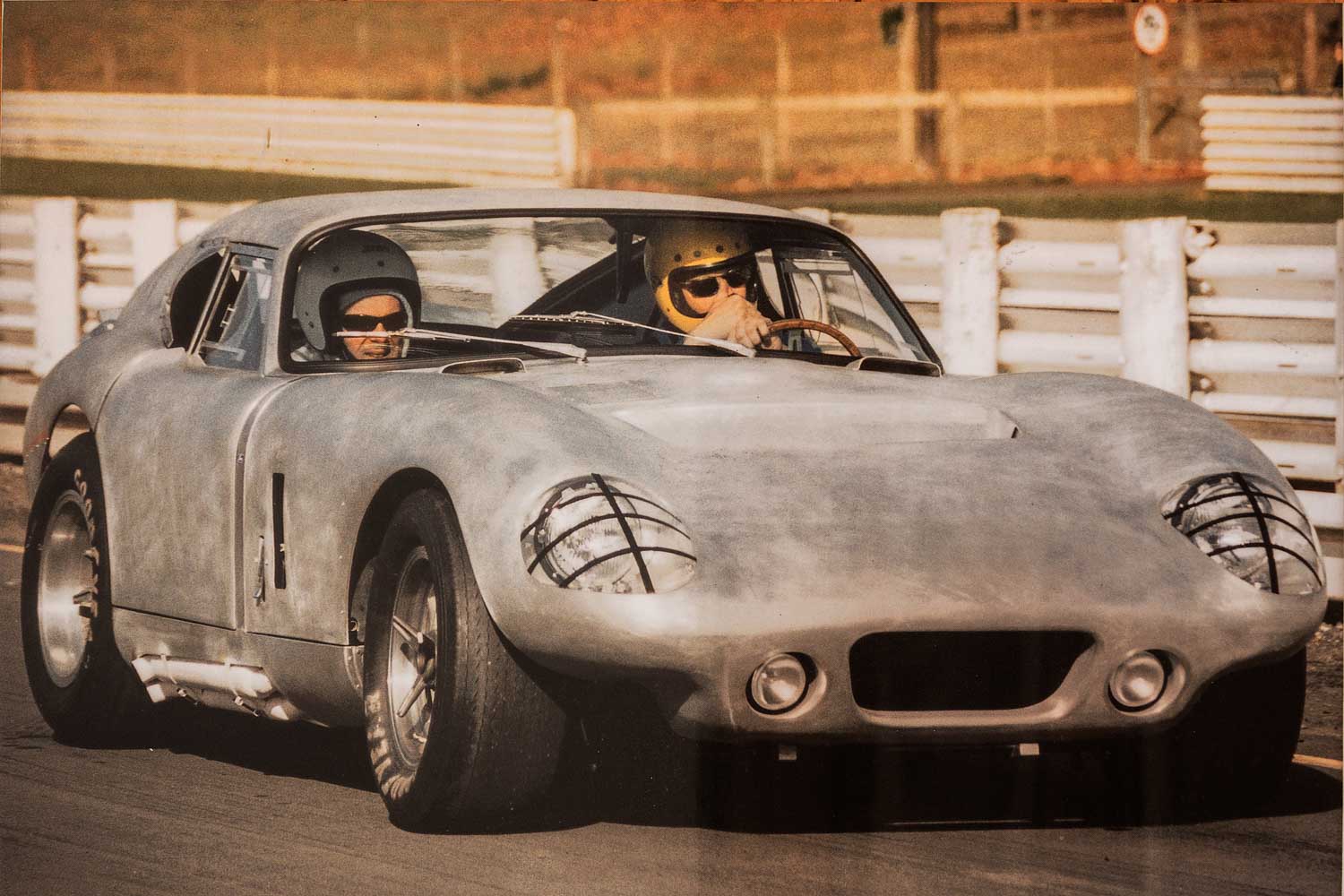

The person who carried out many of these modifications in 1964 was a Kiwi — John Ohlsen. As well as working on the FIA Cobras, he also worked alongside Pete Brock and Ken Miles to develop a more aerodynamic version of the Cobra that could take on the Europeans on their home turf. Brock designed a closed-coupe version of the Cobra with assistance from Miles, a well-known British driver and engineer.

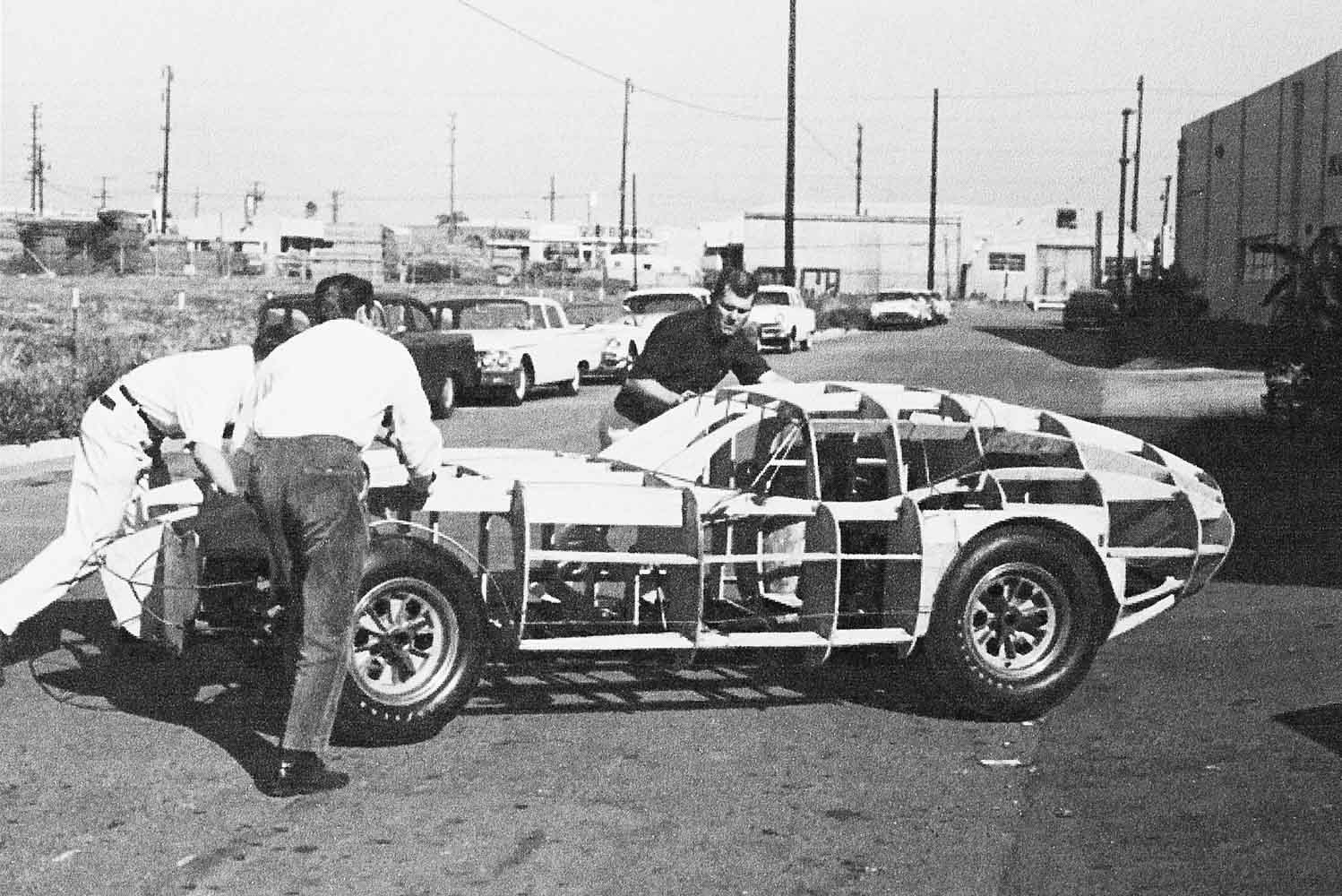

Shelby’s US-based crew really didn’t want to become involved with the coupe, but John — then only working on a temporary basis with the team — quickly became interested in the project. As such, he, along with Brock and Miles, were the only people involved in the development and building of the Daytona coupes.

The result of their labours was tested for the first time on February 1, 1964 at Riverside. With Miles at the wheel, the coupe demolished the previous record held by a Cobra roadster by over three seconds — proving the worth of its aerodynamically sound design.

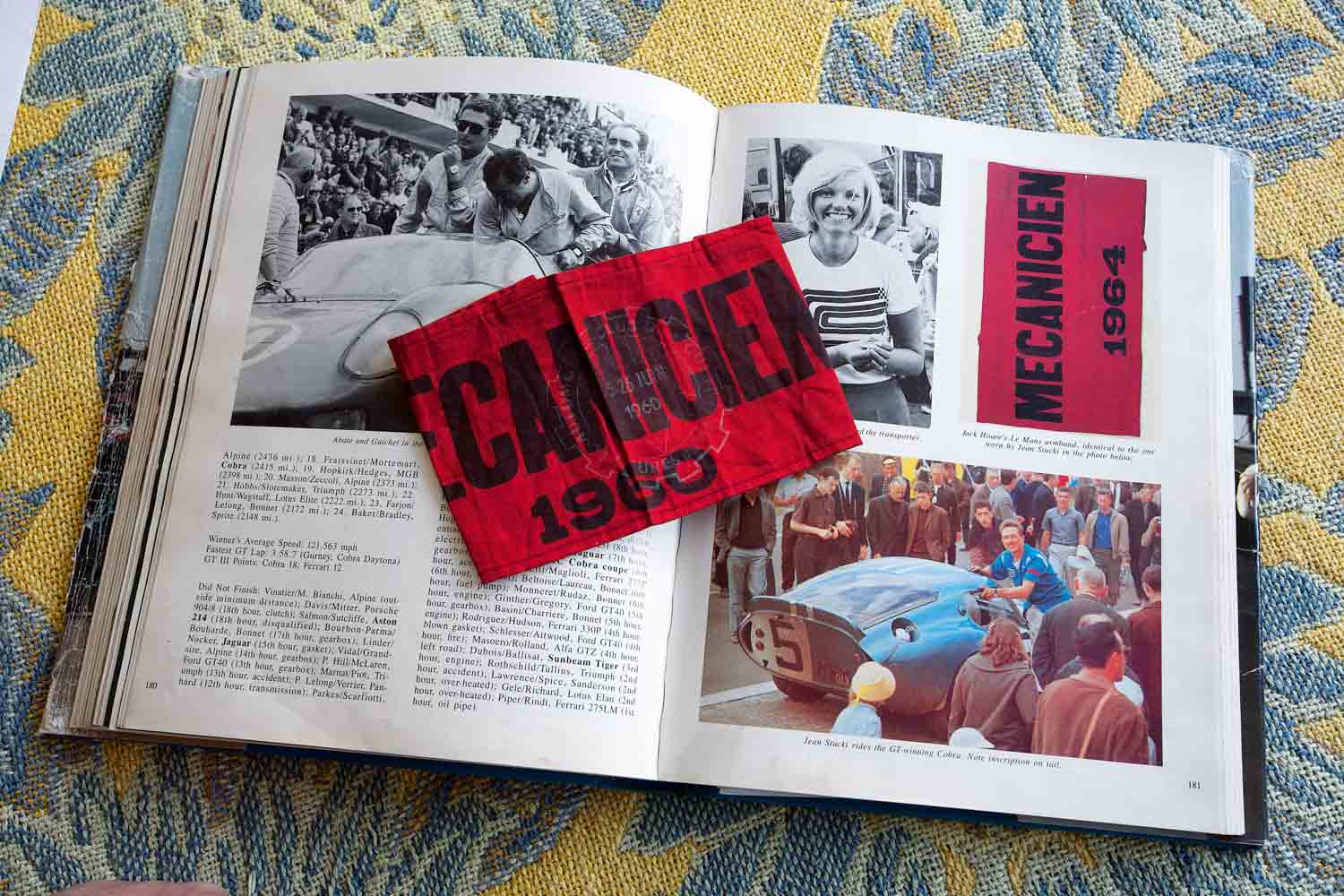

The Daytona eventually won the FIA GT Championship as well as the GT class at Le Mans — thus fulfilling Carroll Shelby’s original dream of beating Ferrari.

Just as a bit of a Kiwi aside, John Ohlsen wasn’t the only New Zealander involved with the Cobra — Chris Amon handled much of the development driving for the 427 Semi-Competition (SC) Cobra prior to that version being homologated for racing.

Fast-track career

Born in Takapuna on November 13, 1937, John first entered the workforce as an apprentice panel beater before switching to becoming an apprentice mechanic. Like a lot of young men, he was attracted to motorsport and was soon volunteering his services to local racing car teams. This included working on Stan Jones’ famous Maybach Special — winner of the very first New Zealand International Grand Prix (GP).

As well, John soon showed his talent for building cars, constructing his first Ford V8-engined highboy roadster in 1957. Over the next few years, he built a further three highboys, racing one at Ardmore and, in another, actually matching the 1956 lap time set by Stirling Moss in a Maserati 250F — although the GP circuit did contain a chicane on the straight when Moss set his time. During this era, John got to know some of the overseas stars during their brief excursions to New Zealand to enjoy our summer racing, including Carroll Shelby, who, at that time, was competing in a Maserati.

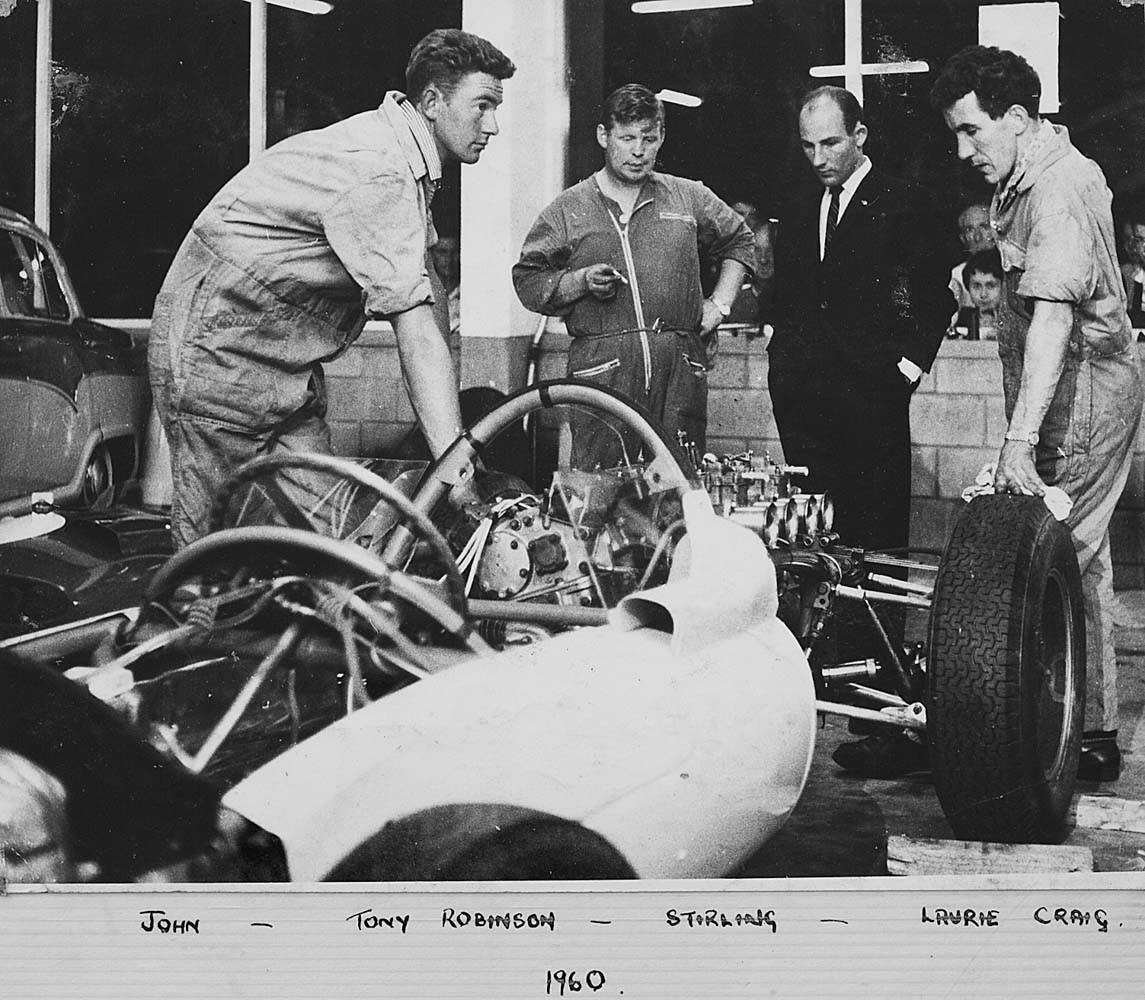

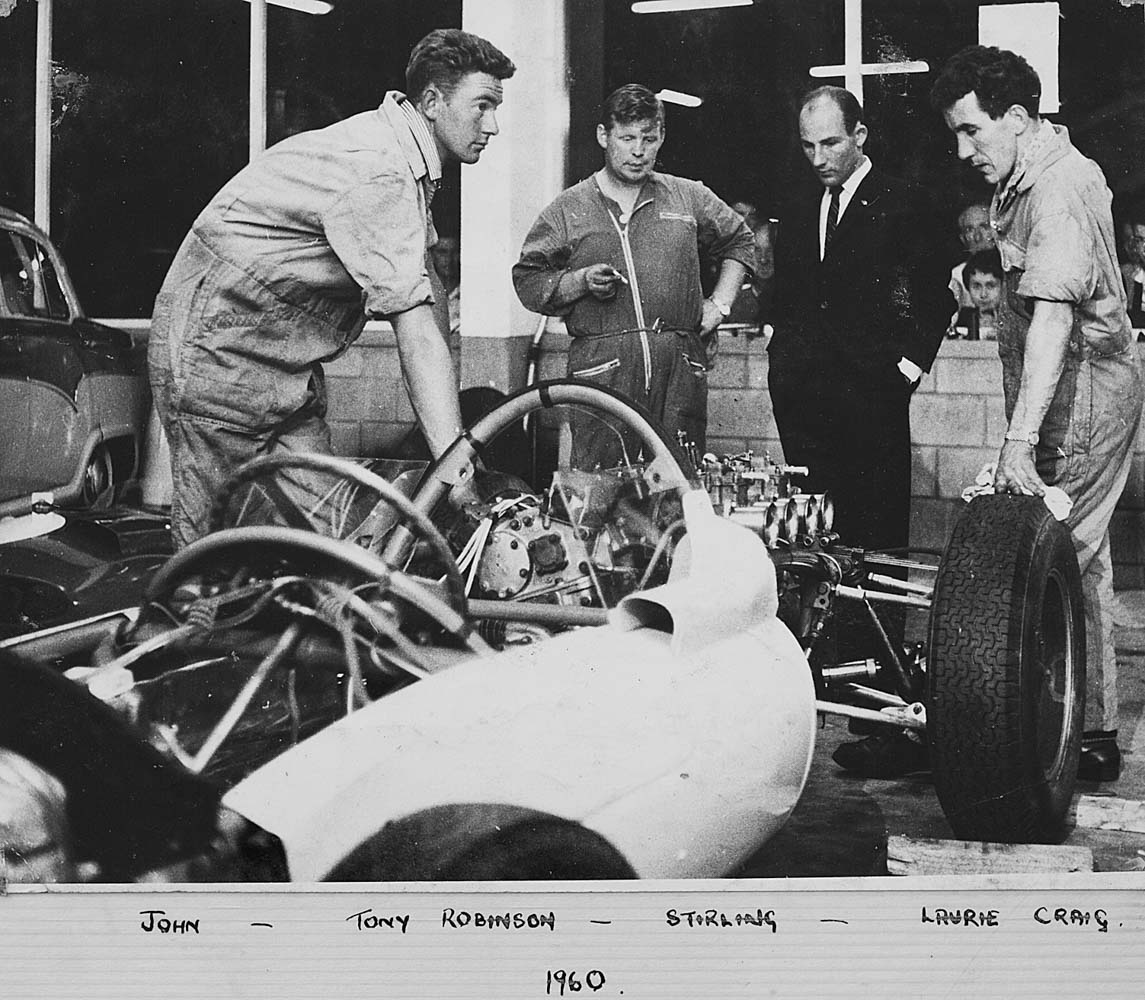

This exposure to international racing celebrities undoubtedly spurred him into making his next step. In 1959, he worked with the Yeoman Credit racing team, which was then running a Cooper-Climax for Stirling Moss. This led to John being offered a position with the team in Europe. So, in 1960 — accompanied by fellow Kiwi and future Lamborghini engineer Bob Wallace — John left New Zealand, travelling to Italy to visit the Maserati factory.

While waiting for the Yeoman Credit contract to start, he worked on the Corvette entered by US driver Lloyd ‘Lucky’ Castner for the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans race and also helped the new Scarab racing team. Alas, the Yeoman Credit deal never came to much, as both the drivers — Chris Bristow and Harry Schell — were lost following on-track accidents.

Travelling from mainland Europe to the UK, John initially found employment at Donald Healey’s speed shop, and, once this concern had been taken over by John Sprinzel and Paul Hawkins, he found himself helping the new owners develop an aerodynamic competition version of the Austin-Healey Sprite — the Sebring Sprite. John and Hawkins quickly became best mates, and, indeed, John would later name his son Paul.

Over the next couple of years, he became something of a motorsport gypsy, working for French millionaire racer Jean Moench in Paris, before heading back to the UK and Ian Walker’s race team. Then, in 1962, John travelled to the USA for the first time as part of Frank Gardner and Graham Hill’s Can-Am campaign. That team used Carroll Shelby’s Venice workshop as its base, and, when Gardner and Hill returned to the UK, John stayed behind to work with Shelby.

Kiwi snake charmer

One of John’s earliest tasks for Shelby was to build the first Cobra coupe — a feat he accomplished in a mere three months in 1963.

Ironically, Enzo Ferrari had used his undoubted influence to bend FIA rules to his advantage, but, in the end, he was hoist by his own petard, as Shelby used those same rules to produce a Ferrari-beating version of the Cobra.

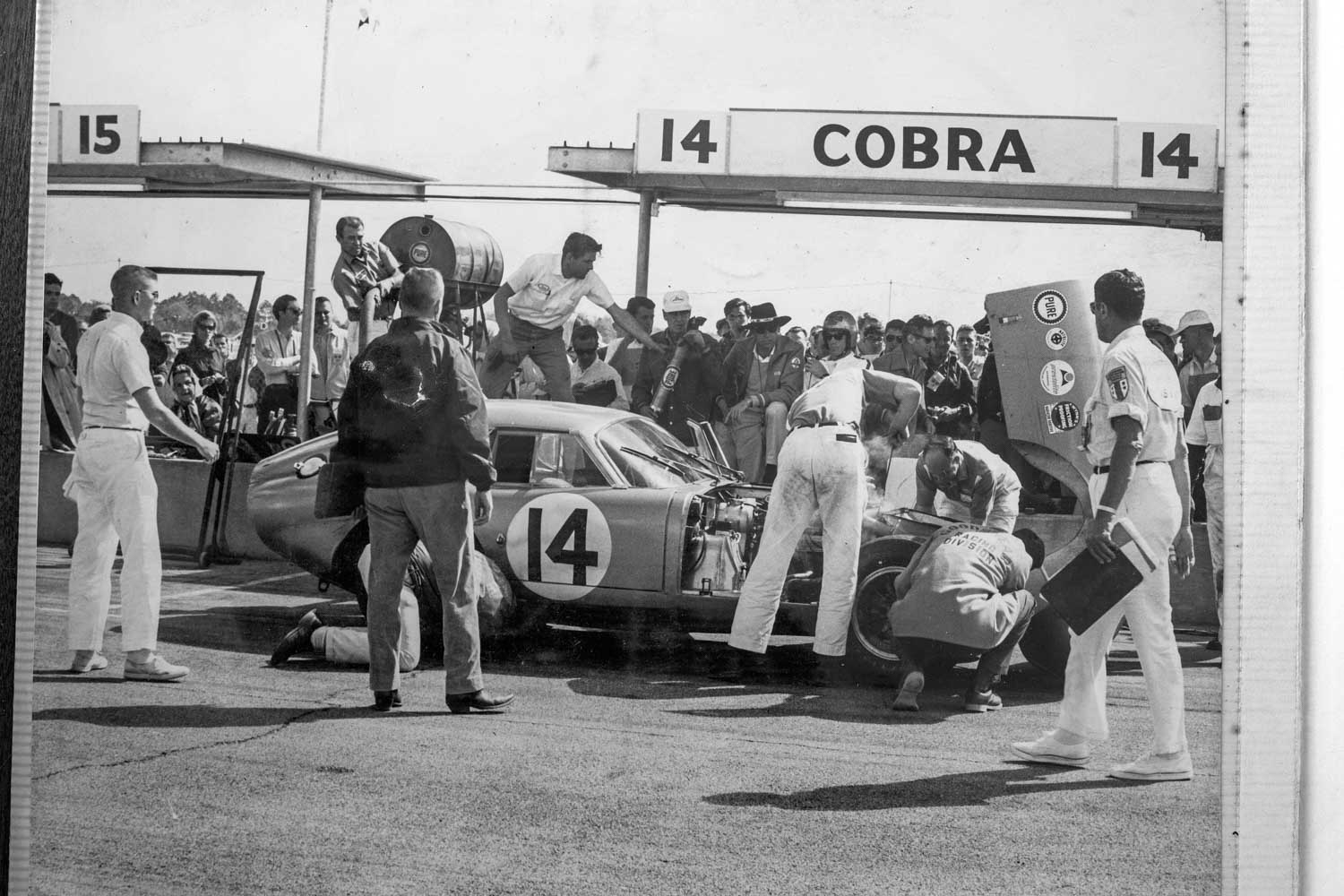

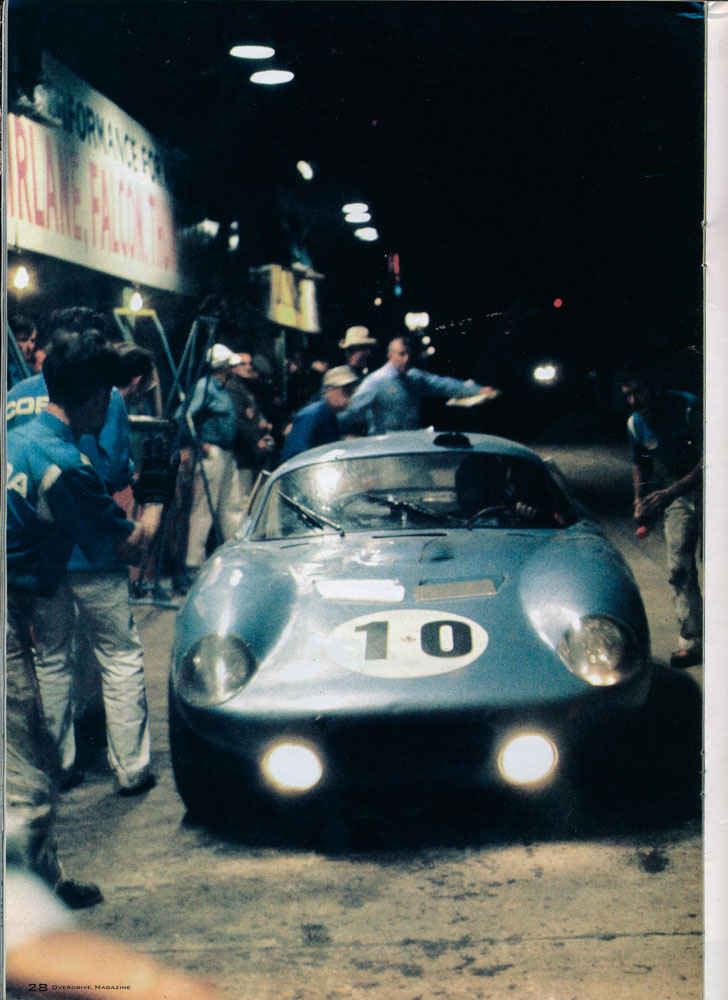

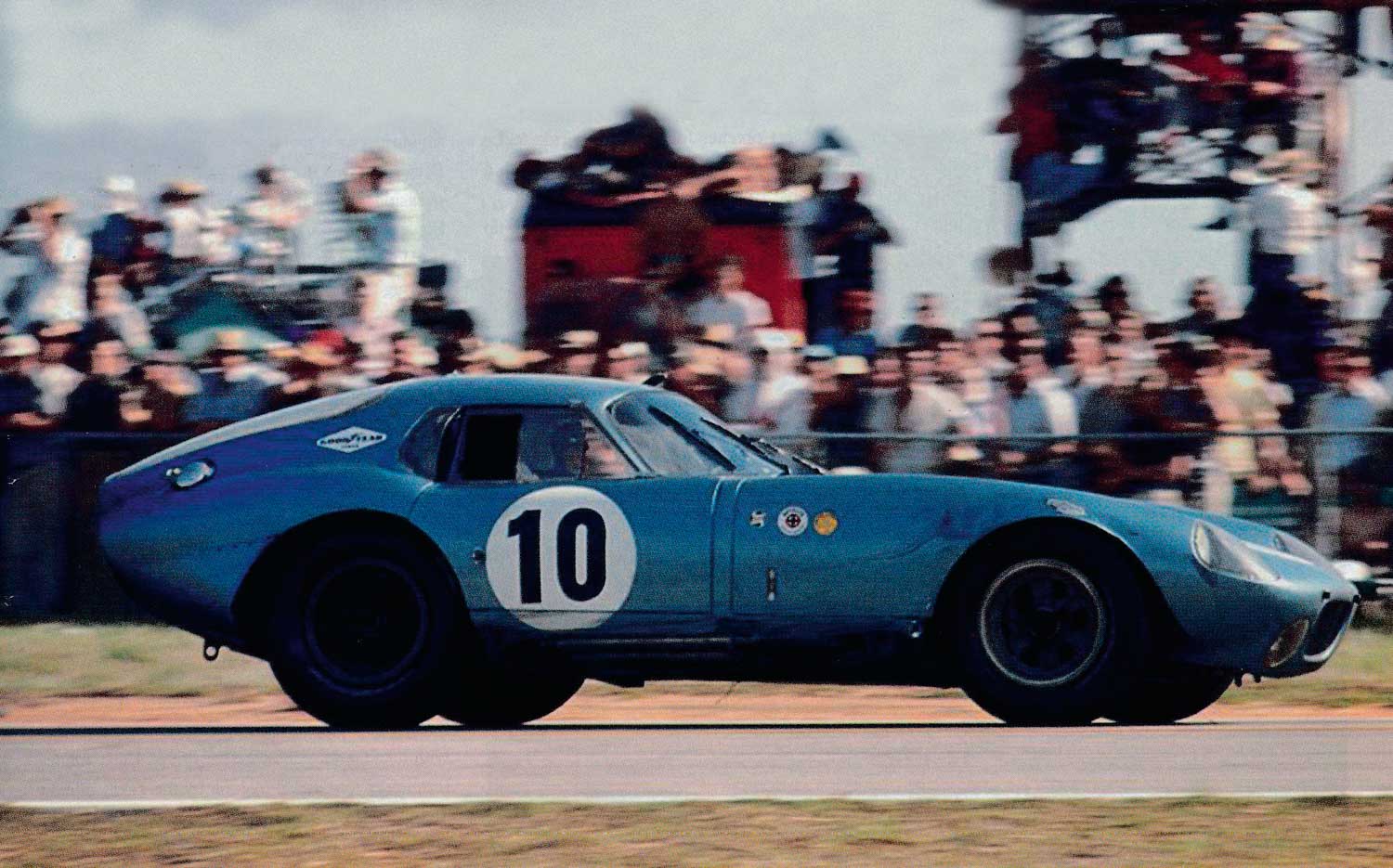

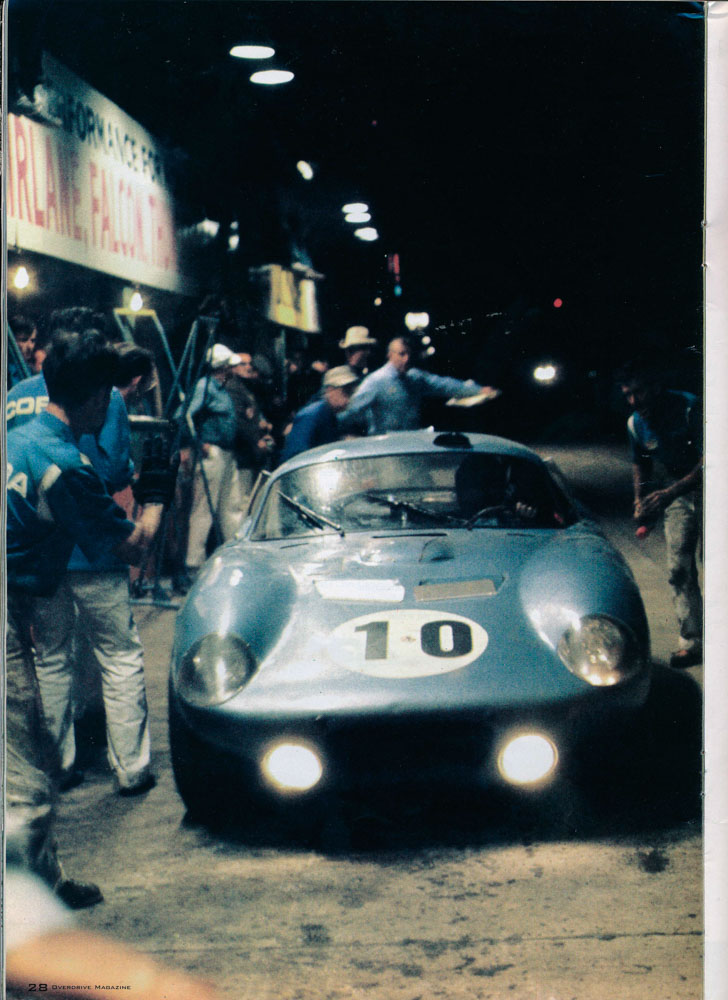

The first of these giant-killing coupes was raced at the 1964 12-hour 2000km race at the Daytona Continental in Florida — hence the cars being later named ‘Daytonas’. Favourites for the race win were the large contingent of Ferrari GTOs, but, unhappily for the Italian marque, the Cobra coupe rapidly proved itself to be the quickest car on the track.

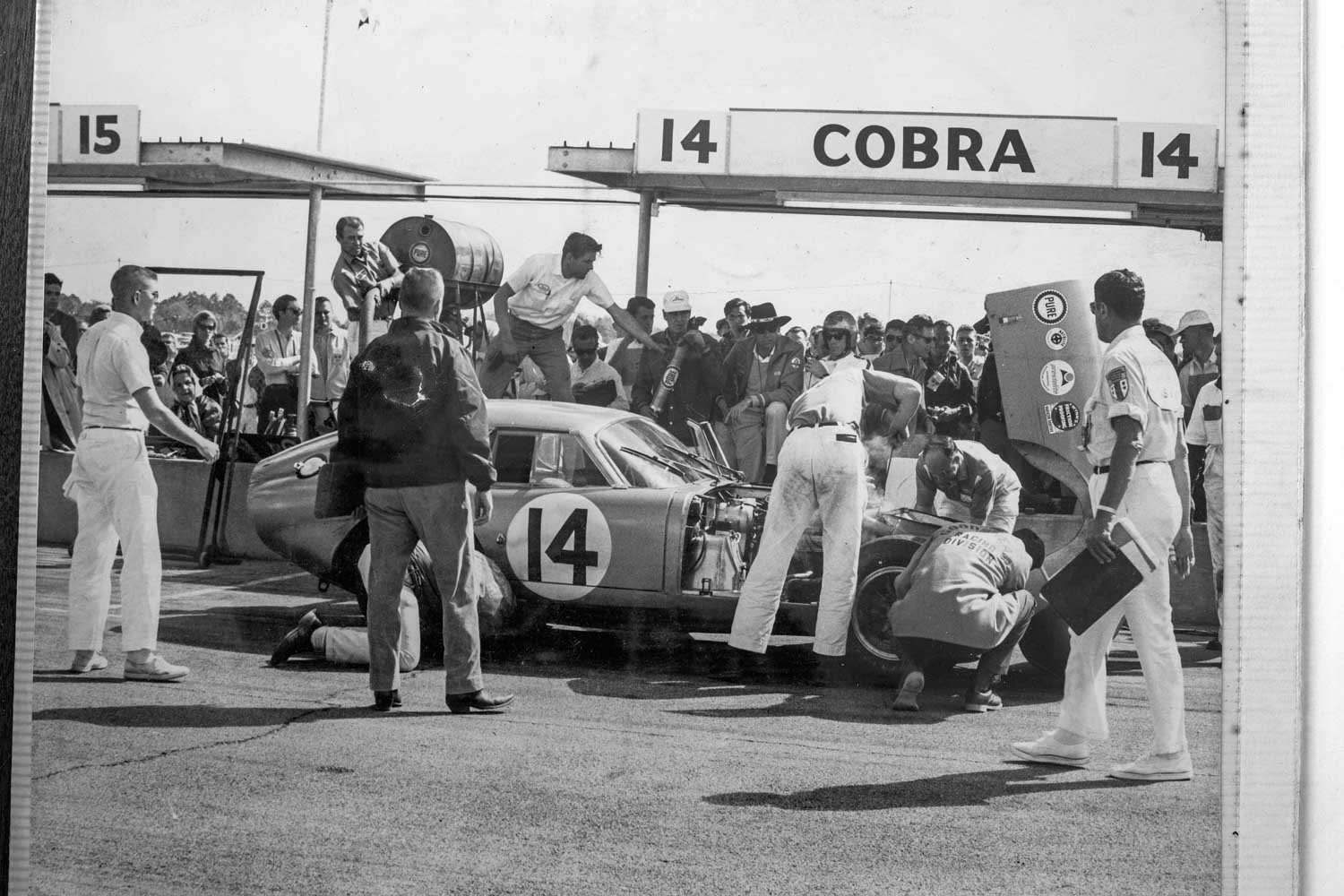

However, at Daytona, while well in the lead, the Cobra was taken out of contention following a pit fire that also resulted in John being badly burned — which led to him being nicknamed ‘Fireball’ Ohlsen!

Later, at the ’64 12 Hour GP at Sebring in March, the newly-named Daytona coupe took its first GT class win — this achievement impressing Ford sufficiently for it to provide backing for Shelby’s attempt at winning the World GT Championship as the series moved to Europe.

Then four roadsters were entered in the Targa Florio for April 1964, plus Spa in Belgium in May, where three roadsters and one Daytona were entered.

At the 1964 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Shelby was undoubtedly proud to see Jo Schlesser record a top speed of almost 192mph in his Daytona down the Mulsanne Straight during practice.

Building on success

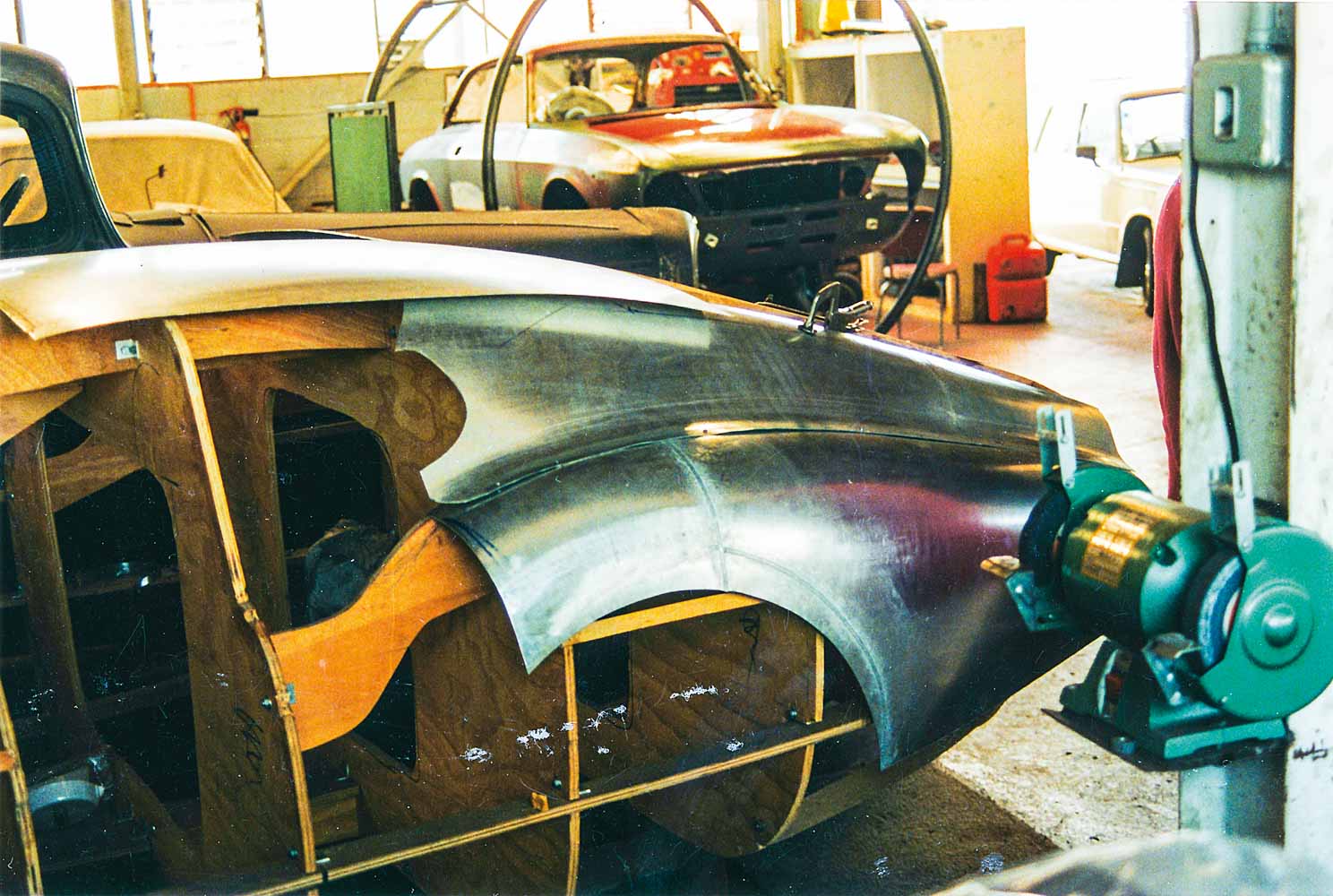

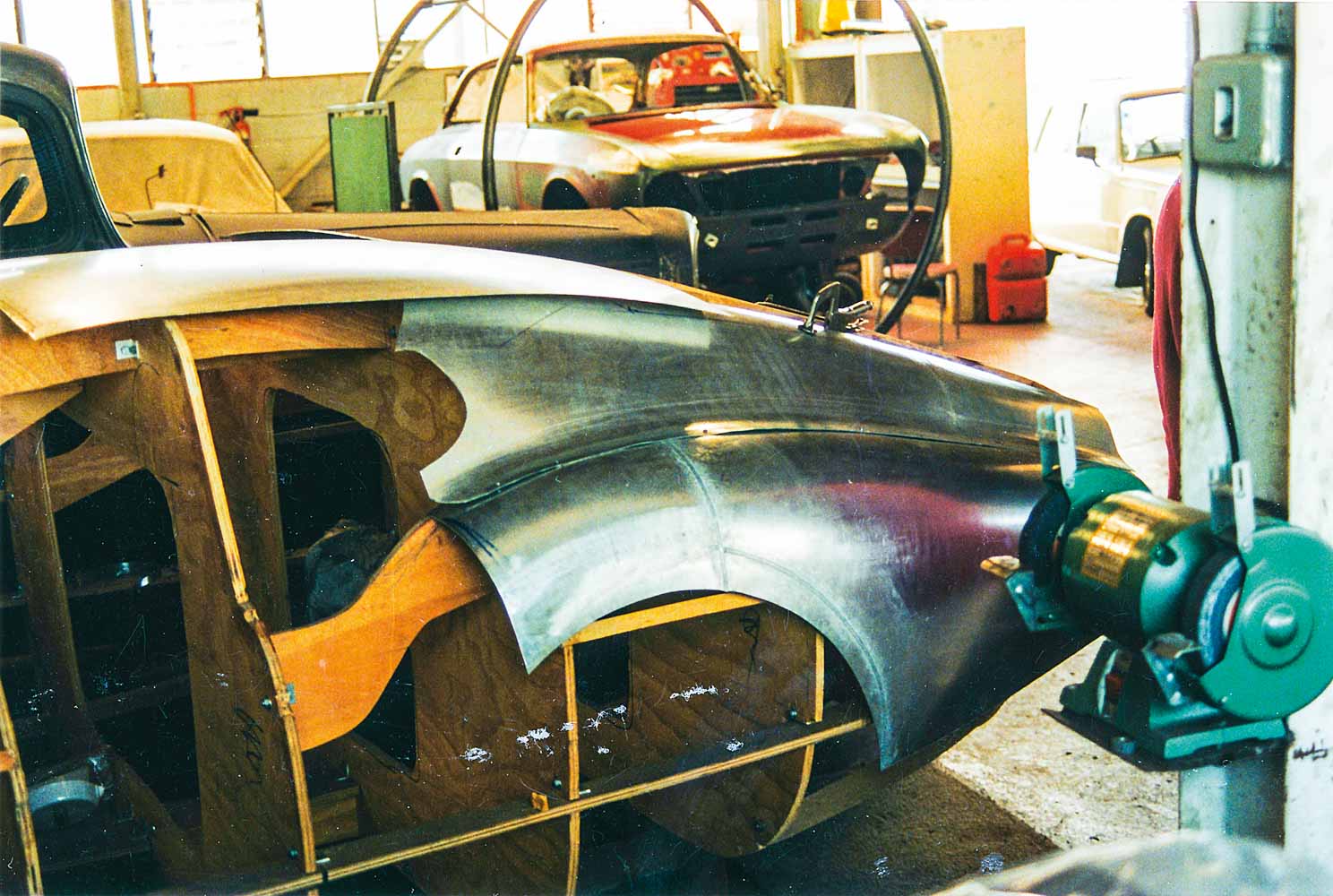

To facilitate the car’s European campaign, the plywood body buck originally built by John Ohlsen was shipped to Carrozzeria Gran Sport in Modena, Italy. There, the five coupes required for the 1964–1965 season were built. Initially, the Italian craftsmen working on the coupes believed they were making an improvement on Brock’s original design by altering the car’s roofline, and thereby adding in two more inches of headroom.

This came about as the result of a mistake when the chassis was built — the cowl hoop being two inches taller than the first coupe. The Italian coachbuilders have carried the blame for this mistake for years, but, in fact, they only made the coupe body to fit the chassis. Anyway, as it turned out, the extra height of that initial car proved useful, allowing it to be raced by Dan Gurney — a much taller driver than Ken Miles, who the car had been originally designed around. The downside, though, was that the Gurney coupe had a marginally slower top speed due to its different roofline. All subsequent coupes were constructed under the personal supervision of John — now fully recovered from the burns he’d received at Daytona — so that error was corrected for the remaining cars.

John also made a trip back to the UK, where he supervised the construction of another Daytona coupe for John Willment’s racing team. Shelby had refused to supply a coupe to Willment, so the team simply commissioned John and Frank Gardner to build one. At the same time, AC itself caused something of a sensation when it road tested its own version of a Cobra coupe on Britain’s M1 motorway one quiet early morning. Recording a maximum speed of 298kph and following suitably purple prose in the British press, AC carried the can for the later imposition of national speed limits.

Interestingly, the AC coupe was built following a telephone conversation with Carroll Shelby, who described what his new coupe looked like, with AC basing its design on Shelby’s description.

With his involvement with the Daytona coupes accomplished, John was now appointed to the role of Shelby’s chief mechanic for the 1964–’65 racing season — the team having switched over to the new Ford GT40.

The return home

John continued working for Shelby until 1966, when, after injuring his back, he took a complete change of direction and started working for a Jaguar specialist in Santa Monica. After three years there employed on numerous film stars’ Jaguars, he became keen for another change, which prompted a move back home in 1969. However, Leo Geoghegan wanted him in Australia, so after just 10 days in New Zealand, John and his wife, Jean, crossed the Tasman.

Unfortunately, that deal fell through, so a month later he returned to work for Shorter’s Jaguar in Auckland. John also worked for Mark Petch’s company, Marave Automotive, and became involved with building the Katipo F5000 single-seater and the Holsen — a Katipo Formula Ford.

John and Jean’s son, Paul, was born the year after the couple returned to New Zealand.

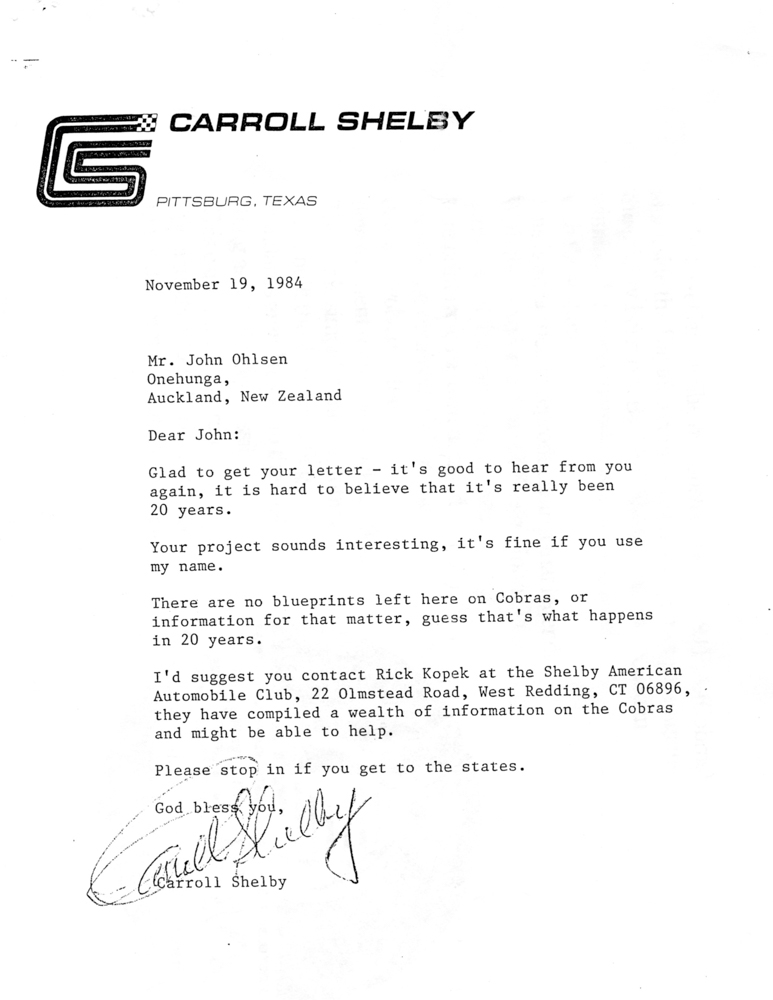

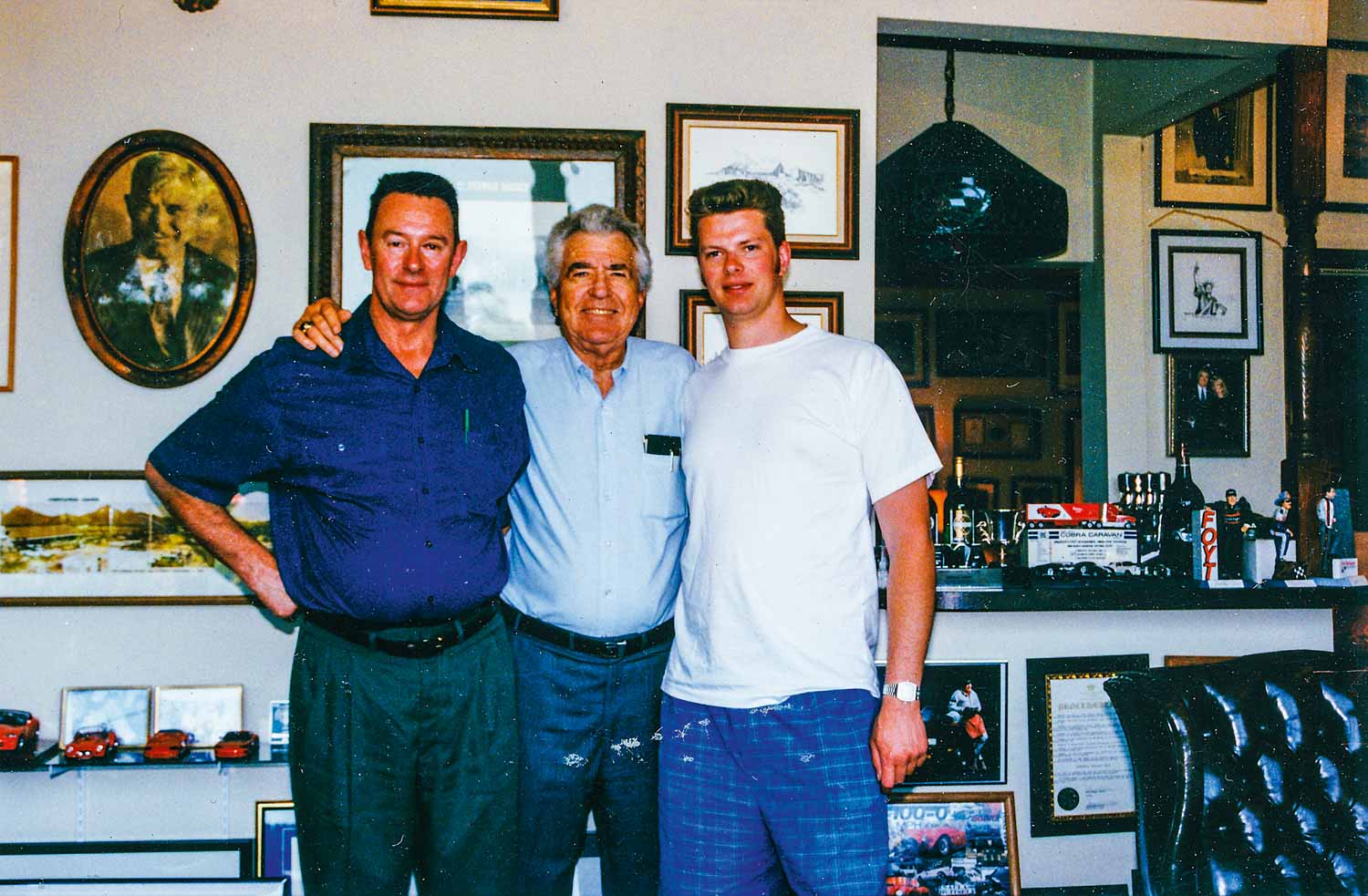

In early 1970, John went into partnership at Cassino Motors in Newmarket, and, some 14 years later, in 1984, he established his own business — John Ohlsen Developments in Onehunga. He began to consider working on the rebuild of a rare 1964 Shelby Cobra FIA 289, of which just six were originally made at Shelby, and he and Jean travelled to the USA in 1986, after John had already begun work on his first FIA 289 chassis. There, they visited the Shelby factory to collect the plans and photographs that would help them to further develop a Shelby FIA 289 replica with full support and approval from Carroll Shelby.

Utilizing self-built jigs, Shelby’s original plans, and his own first-hand experience, John’s first FIA 289 was initially intended for his own use. However, a friend — Christopher Hook, a keen Cobra enthusiast — wanted to take over the project. This car was completed with a hand-beaten aluminium body built by Tempero in the South Island, but further work on the body was deemed necessary — this being handled by a Napier-based coachbuilder. Once completed, the car was tested at Pukekohe by John.

Alas, Hook ran into financial difficulties, and the car was subsequently sold to an Australian enthusiast, who competed with the FIA on several Targa Tasmania events before finally selling it on to a Melbourne-based Cobra collector.

Two more roadsters would be built — one for Auckland builder Sam Champion and another for Peter Dean, a graphic designer. Indeed, the ‘Champion’ chassis could be regarded as the first of the Ohlsen FIA cars, as it was constructed to the rolling chassis stage prior to the building of Chris Hook’s car. However, work on the Champion Cobra was temporarily shelved in order to build the car for Hook. The rolling chassis later left John’s workshop on the same day that the Peter Dean Cobra arrived back from Ivan Cranch with its fully completed, hand-beaten bodywork. This Cobra is still owned and driven by Peter Dean, who now lives in the South Island.

The other rolling chassis remained in Sam Champion’s garage until purchased by Rogan Hampson in late 1997. Hampson commissioned Cranch to build a body for the car.

So, to confirm the build sequence — Rogan Hampson’s car was the first chassis built but the last to be completed, Chris Hook’s was the second chassis built and the first to be finished, and Peter Dean’s car was the third and final FIA 289 to be completed.

During all these builds, a Daytona coupe was started for a Napier-based customer, but the car remained unfinished and was eventually sold some 11 years after work began, to a company in Canada.

A new generation

John’s son, Paul, joined his father in the family business during 1988, learning plenty from his dad along the way, as well as bringing new clientele with him.

Sadly, after commencing work on a second Daytona coupe, John died suddenly in 1998, just three-quarters of the way through the build. With American Ford man Jay Russell awaiting delivery of the coupe — due only 10 days after John’s death — Paul and Jean Ohlsen started work on completing the Daytona, which took a further 10 months. The car was to be tested by Chris Amon on June 20, 1999 — however, with Amon unable to make it, Paul undertook the shakedown tests himself. He even managed to give Jean a few laps in the vacant area where a passenger seat should have been — all while she held John’s ashes: his final ride in a Cobra!

After 20 or so laps in total — with the only issue being a small leak from an oil-cooler line — the car was returned to the Ohlsen workshop before being shipped to California in July 1999. With this, the days of the Kiwi–Cobra connection were essentially over.

John’s wife Jean, and son Paul, still ran the family business in Onehunga until late 2013. Nowadays, Paul runs the business under the same name, mainly contracting to do race car preparation and maintenance, much like his dad did many years before him.

Photos: Ohlsen family archive