data-animation-override>

“The weekend of August 15–16 will see The Motorhood feature Brenden Van Schooten’s amazing Ferrari P4 replica. To wet your appetite, here’s a brief history of the P4, and what the model meant to Ferrari”

Ferrari’s revenge

In 1967, Ferrari introduced a sports-racing car that has since been hailed as one of the most beautiful cars ever built — the 330 P4. As with all Ferraris of that era, the number ‘330’ related to the cubic capacity of each cylinder of the car’s V12 engine, while the P4 designation denoted this model was the fourth prototype for racing. As you’d expect, each P4 was hand built utilizing alloy panels designed by Pininfarina and formed over a tubular chassis. It was a car intended for racing only, and a road-going version was never produced. Only three P4s were ever made, while one P3 was upgraded to P4 specifications.

It was powered by a V12 producing 336kW (450bhp) with a total weight of only 800kg, and Ferrari intended the P4 to go head-to-head against Ford’s GT40 at Le Mans — the Ford, of course, having been originally designed to beat Ferrari at its own game after Enzo Ferrari backed out of a deal to sell his historic company to Ford.

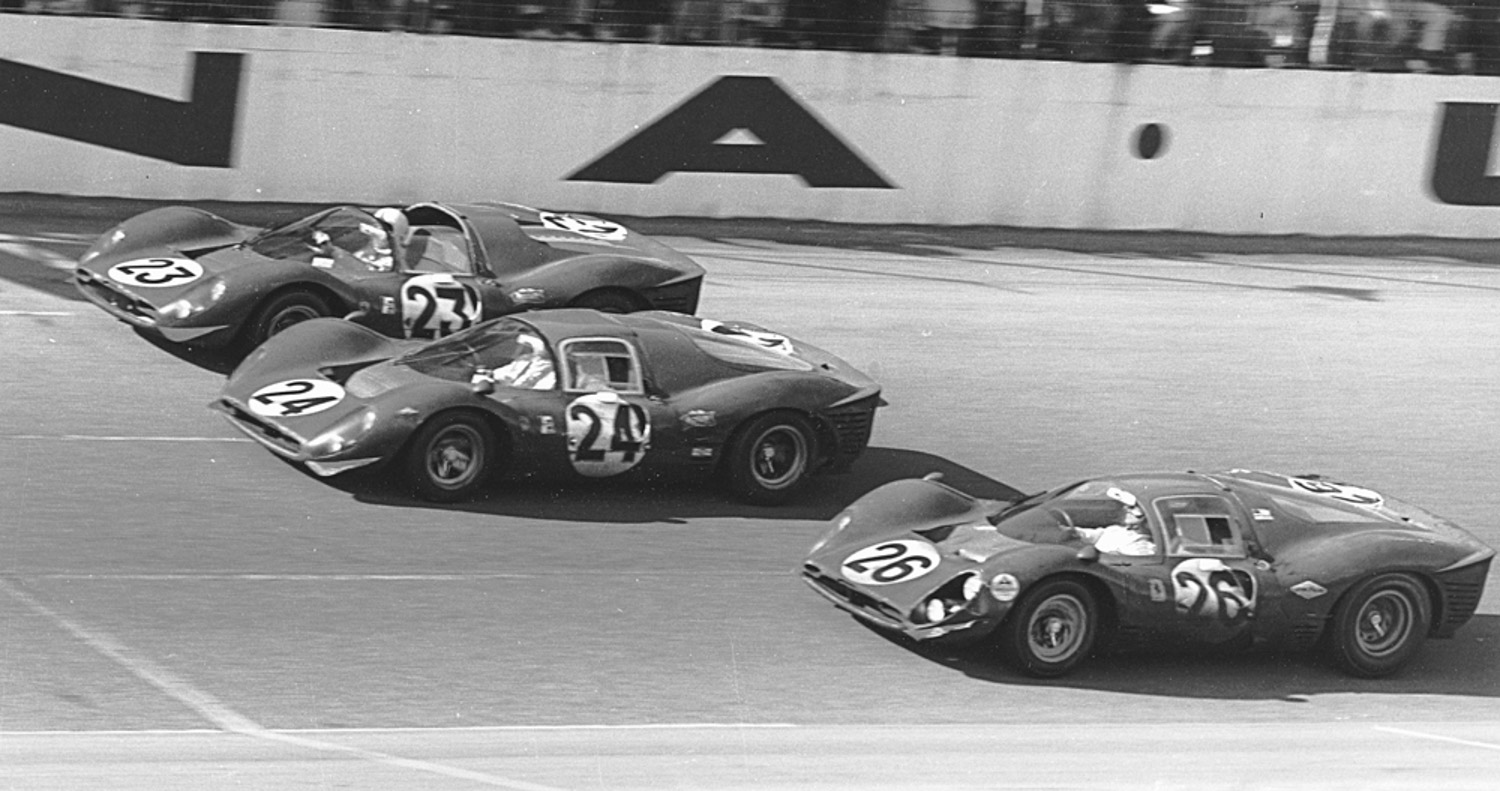

Having already been humiliated by Ford at Le Mans in 1966, Ferrari was out for revenge, and the first opportunity arrived at the following year’s 24 Hours of Daytona race.

Only two 330 P4s were available for the race, Ferrari’s third entry being a converted P3. Ferrari’s number-one car saw Lorenzo Bandini team up with our very own Chris Amon who, ironically, had driven the 1966 Le Mans–winning GT40 along with Bruce McLaren. In the event, Ferrari staged a glorious one-two-three finish, with the Bandini/Amon P4 taking the chequered flag. The best Ford could manage was sixth place. The combination of Bandini/Amon and the P4 repeated their Daytona success at the Monza 1000km race in April, with the Mike Parkes / Ludovico Scarfiotti P4 in second place.

Alas, when it came to the big race of ’67 — the 24 Heures Du Mans — the GT40 driven by Dan Gurney and AJ Foyt took out overall honours, although Ferrari managed to nail down the second and third spots. If that wasn’t enough, for 1968 the international racing authorities altered regulations, reducing eligible engine capacity to 3.0 litres, rendering the P4s with their 4.0-litre engines redundant.

Replica heaven

Due largely to the 330 P4’s gorgeous Pininfarina-designed looks and, of course, the scarcity and huge value of the original cars, a large number of replicas of this iconic sports racer have been built over the years — with perhaps those designed by Lee Noble being at the top of the tree. Other notable P4 replicas include the South African BMW V12-powered Bailey–Edwards example. A handful of bespoke replicas have been constructed using genuine Ferrari engines — the 400i V12 being a popular choice — and on the open market such cars can command prices as high as $250,000 while those fitted with lesser engines such as Rover V8s can be snapped up for considerably less.

Millionaires only

The upgraded P3 was destroyed in a crash at Le Mans, so only three cars remain — two of these do not have roofs, being Can-Am racing versions, so only one hardtop P4 is still in existence, and it would be estimated to be worth around $20,000,000.

The 330 P4 chassis number 0858 — the ex-Amon/Bandini car — was actually offered for sale via auction in 2009. Interestingly, as well as the Amon connection, this P4 also, briefly, resided in Australia as part of David McKay’s Scuderia Veloce team, although the car only competed in one race at Surfer’s Paradise before being shipped to South Africa.

At auction, the P4 attracted a high bid of €7.25 million, but failed to find a new owner.

Don’t forget to keep an eye on The Motorhood over August 15–16 to see a full feature of Brenden Van Schooten’s Ferrari P4 replica.