data-animation-override>

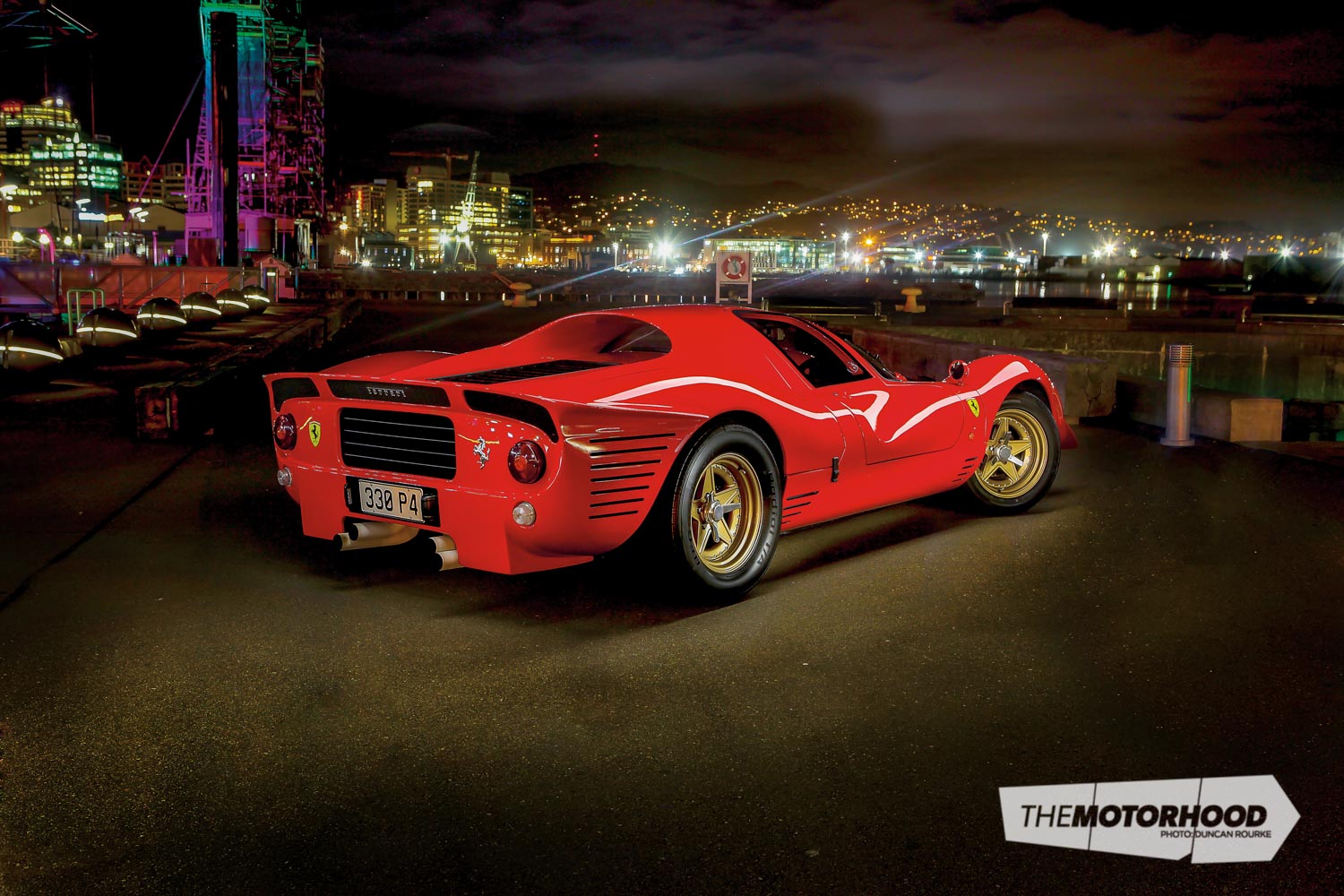

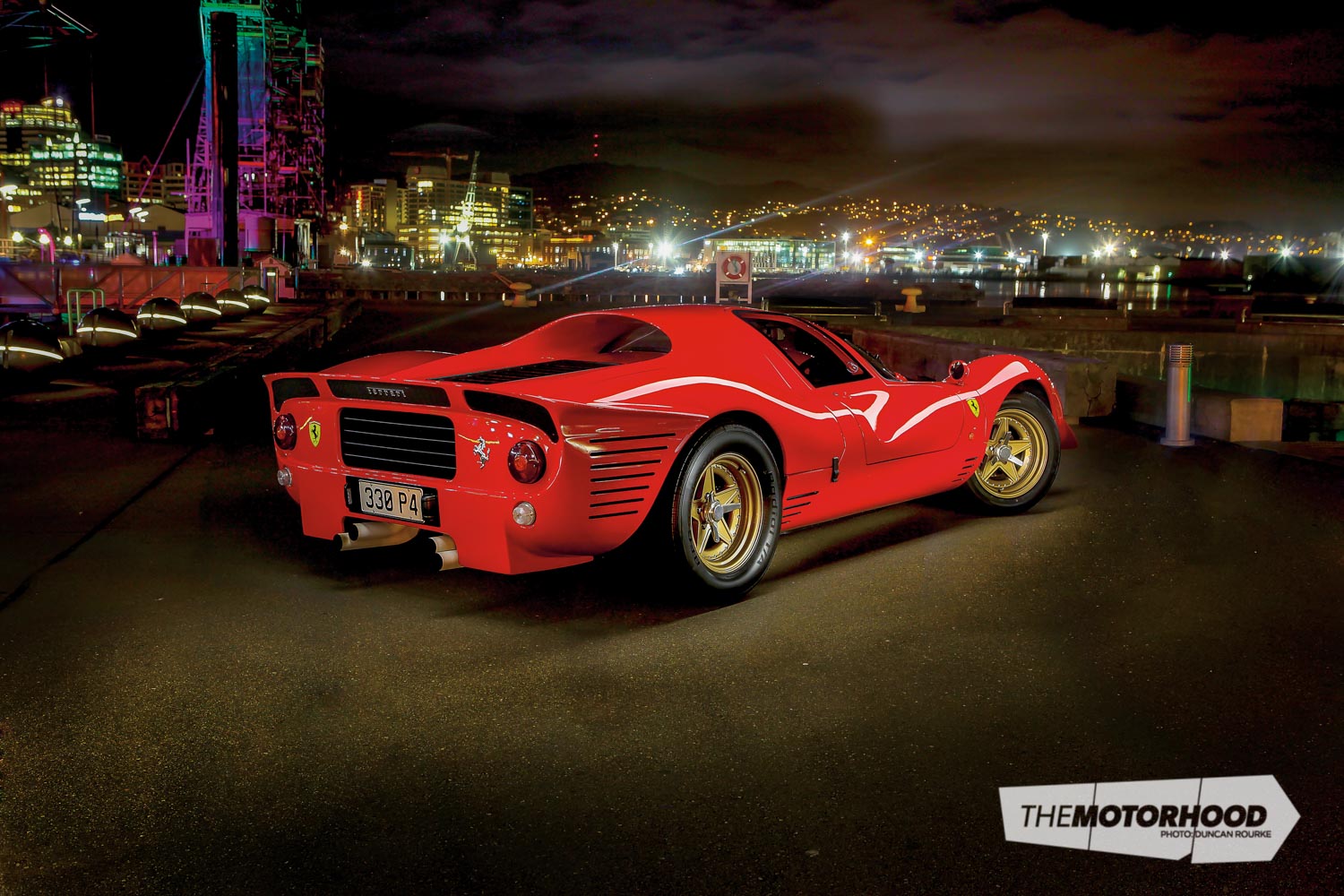

“Recently accepted into the Ferrari Owners’ Club of NZ, this amazing car is the result of around 6000 hours of specialized work”

Brenden Van Schooten met Guy Cross in 2005 at a friend’s wedding in Wellington, and while their partners were entertaining themselves, the boys sat down to talk about cars, as we all do. Guy mentioned that he had just purchased a Series III, V12 E-Type Jaguar convertible in parts, and was about to start a full restoration. Having previously built circuit-racing and rally cars during his 20s, Brenden quickly offered his assistance, thinking that his friend’s Jaguar project sounded like an interesting way to consume his time.

Over the next four years the two friends dedicated about five hours a week to the project, working in a barn up Paekakariki Hill Road near Wellington. The ‘workshop’ was freezing cold in the winter and turned into a sauna in summer. Over that period of time Brenden and Guy reassembled the E-Type from 13 boxes of parts, guided by a factory restoration manual.

Then, disaster struck — one sunny day, only three months short of completing the joint project, the barn caught fire and the Jaguar was burned to the ground. It was a very sad day, and both men felt as if they’d lost a family member.

However, three months later Guy found another interesting project listed for sale online — a Ferrari 330 P4 replica. And it was in just as many parts as the E-Type!

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves — first a bit of history.

A noble pursuit

In 1986 an English car builder by the name of Lee Noble — now best known for his Ultima cars and, of course, sports cars such as the Noble M10 and M12 — designed and built the first replicas of the P4. He was fortunate enough to be allowed to take moulds from an original car, and this explains why the bodywork on his replicas is not the same on the left compared to the right. Quite simply, the originals were hand-made for racing, and symmetry didn’t matter. Noble reproduced the P4’s lightweight tubular steel chassis, but instead of alloy body panels he fitted strengthened fibreglass for simplicity. Noble built as many as 50 replicas before selling the rights to Neil Forman, from NF Auto Developments, the engineer who made some of the replica’s suspension components.

Around 1996, Sony International commissioned one of the Noble-designed P4 kits to be built up to display its new $150,000 car stereo system. It was built as a rolling shell with no engine or gearbox, and the interior was made from plywood covered in leather. The car was fitted out with a number of TV screens, huge speakers, and all the rest of the boom-box paraphernalia liked by those youngsters who prefer to wear their baseball caps on backwards. It toured a number of high-end car shows through the world before finishing up in Dunedin, of all places!

Subsequent to Sony removing all its fancy audio gear, a car dealer arranged the sale to a local buyer. Following that, it changed hands a few more times, gradually deteriorating as the years passed by. Finally it was advertised online in late 2009, the owner at the time having to sell up to finance a marriage break-up. Some years earlier he’d modified the car’s chassis to accept a Porsche 911 engine, and had also removed all the body panels.

At the time it was advertised for sale, the replica had been squatting in a garage, buried in rubbish, for over three years. Meanwhile, its body panels had been sitting in someone’s back yard, exposed to the weather. A rebuild would be a major exercise — and a much bigger task than that provided by the aborted E-Type, although at least both Brenden and Guy had seen a completed E-Type before.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained — of course, they bought the car!

A major project

After driving to Dunedin, the pair literally dug the rolling chassis out of the garage, strapped the body panels over the chassis, and filled the back of the tow vehicle with the remainder of the parts. The unearthing and packing process took six hours — all accomplished in the rain with freezing temperatures, with the seller nowhere to be seen. What a start!

“We got questioned about the car at every stop we made on the return trip to Wellington,” Brenden said.

After finally arriving home, and unloading everything, they stood back and wondered what the hell they’d actually acquired.

As Brenden would later say, “It was a mess. We degreased the engine and Porsche 914 gearbox, and spent another six months playing around with the body panels to fit properly.”

Over this time Brenden spent hundreds of hours researching Porsche engines, and was even able to purchase an original build manual for the Noble kit, so at least they knew how to put everything together. Some research went into the notion of importing a Ferrari V12 engine and matching gearbox from the US, but the high costs involved, and the uncertainty of the engine in question’s condition, meant that it was eventually deemed to be outside their budget.

They looked at a Jaguar V12 too, but these are heavy units compared to the 911 engine, which only weighs 128kg — similar to the original Ferrari V12. Some South African–built P4 replicas have been powered by BMW V12s, but Brenden and Guy felt those engines were also too heavy. Even though the power-to-weight ratio would be higher from a V12 such as the BMW unit, it would throw out the balance of the car, and the aim was to have a great looking vehicle that was fun to drive in all conditions. Although it’s lighter, use of a Lexus V8 was also vetoed as the sound would just be wrong. Zero to 100kph times were not even a consideration — the car’s lightweight construction would make the best of even a fairly modest power output. The Porsche engine started and seemed to run well, so a decision was made to stick with it and look at rebuilding the motor with high-compression pistons to give the finished car a power-to-weight ratio similar to a BMW M3 — that could be fun without traction control! Anyway, they reasoned, how many Ferrari replicas do you see with a Porsche engine?

They made a decision to stick as closely as possible to the instructions contained within the build manual that Lee Noble had put together to go with his kits, so they could get as close as possible to what he had designed. After all, they figured that Noble knew what he was doing.

The following 24 months were spent fibreglassing weather-worn, broken or fractured panels, cleaning up the chassis and making the curved dashboard — that took over 200 hours alone! Thousands of hours were spent welding and fabricating custom bits for everything — obviously, you can’t buy parts for a car like this off the shelf — and sometimes items were fabricated twice as Brenden figured out better ways to make them.

Technical details

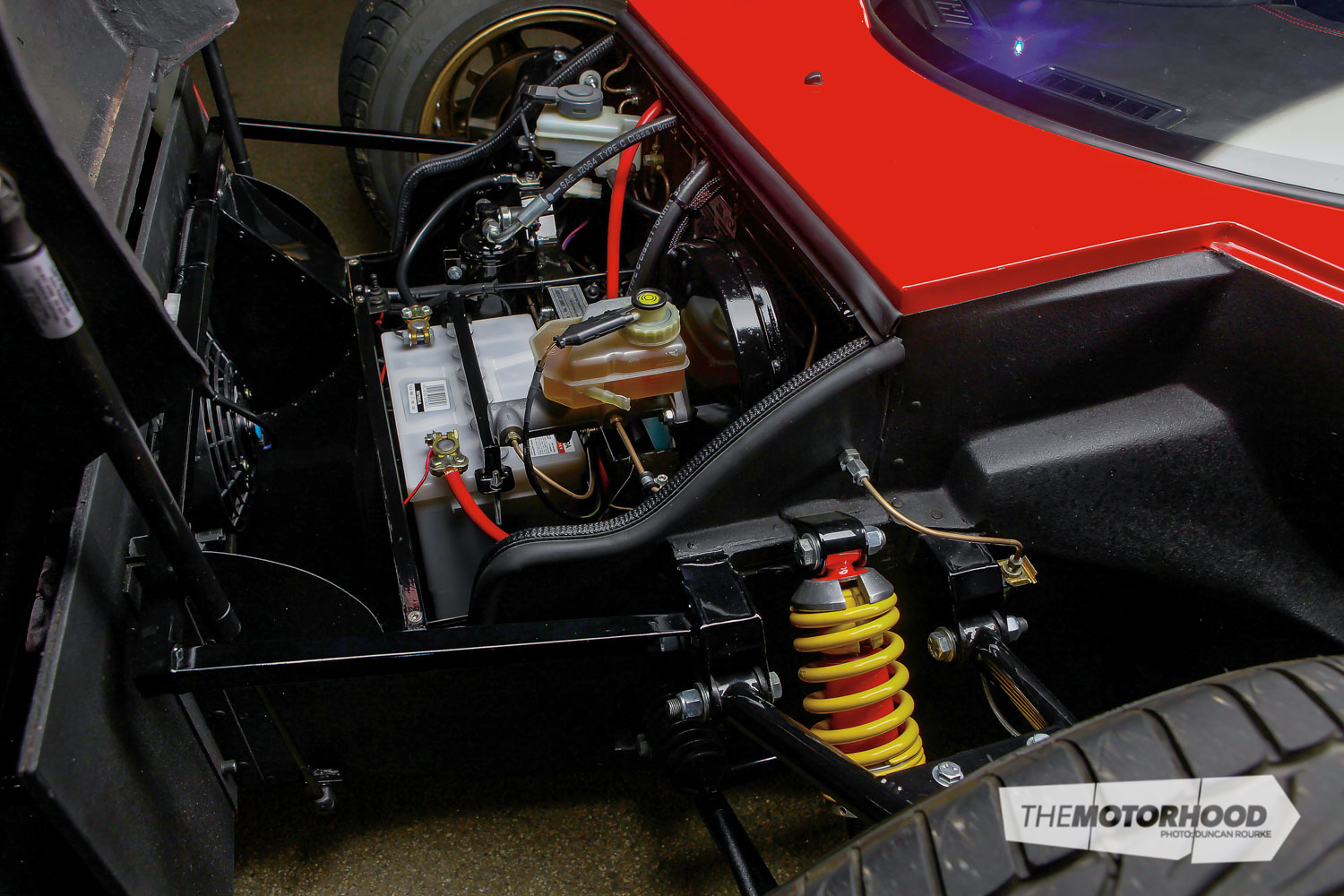

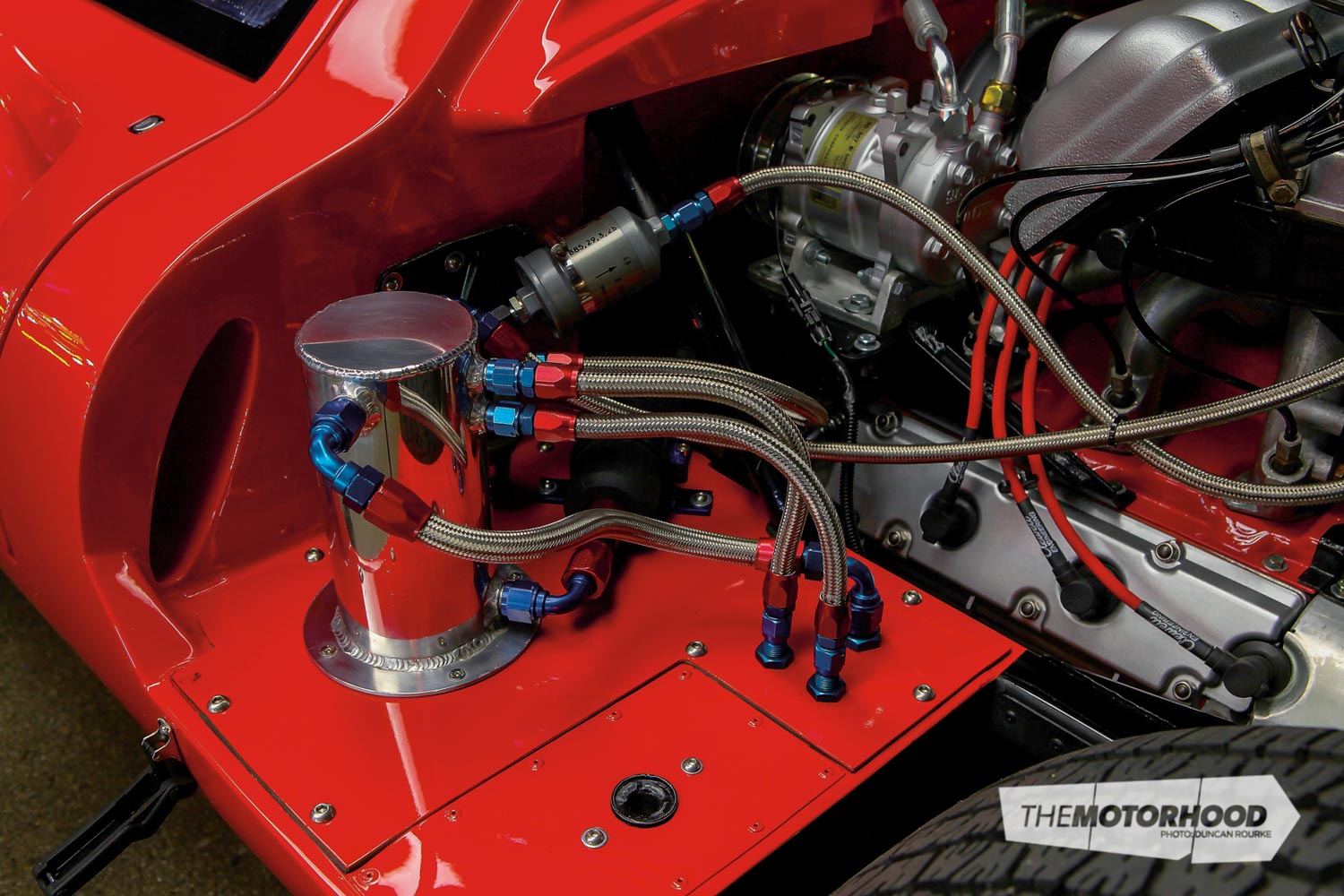

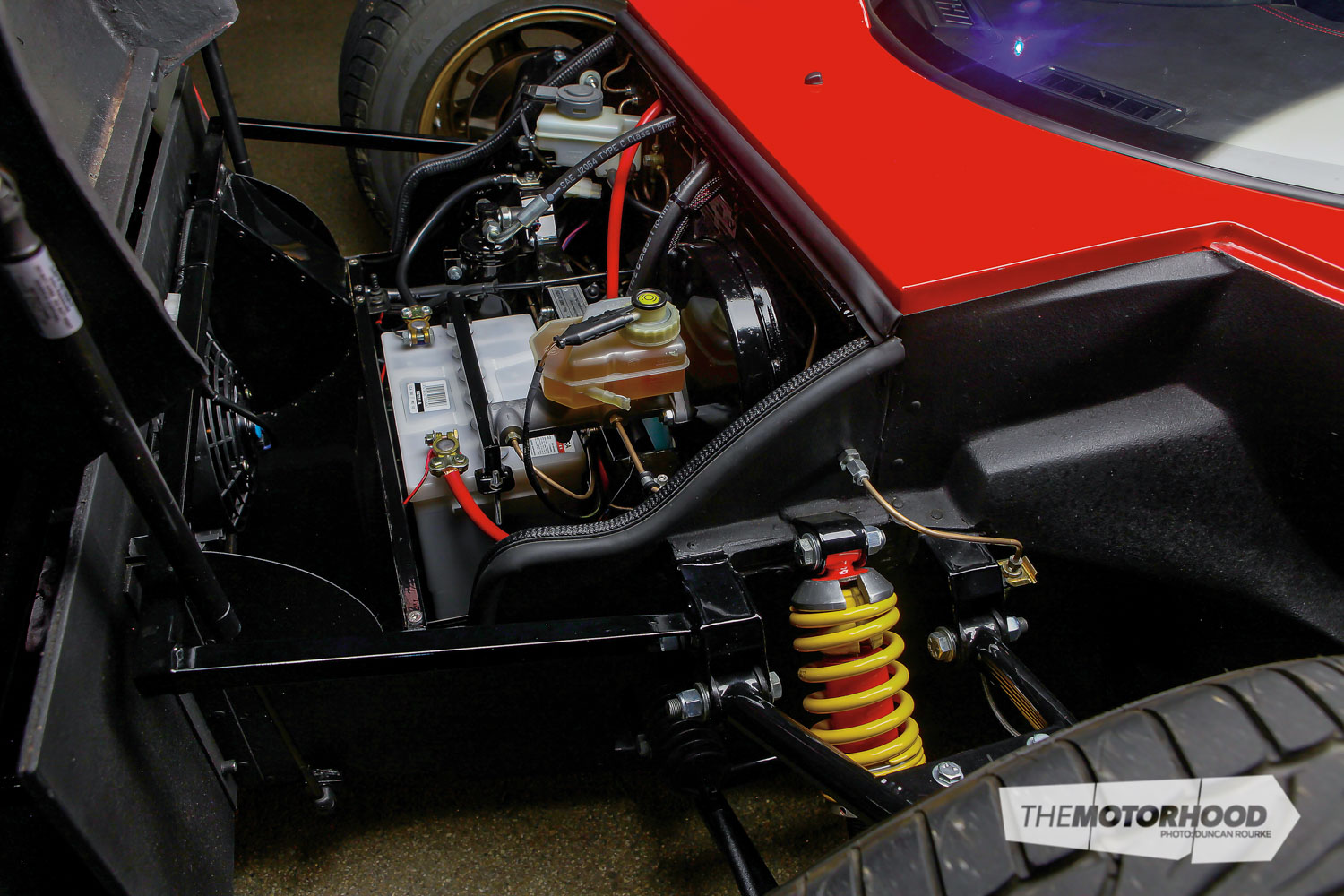

The car’s body and interior panels are riveted and bonded to the chassis for rigidity and strength, and a 65-litre alloy fuel tank was built and resides in the entire length of the left-hand sill — side impact protection for the passenger! An E30 BMW 325i pedal box and brake servo system were overhauled as per the build manual, and a new SD1 Rover steering column was sourced, as the one that came with the car had been shortened. Noble originally recommended using a Ford Sierra XR4i as a donor vehicle for steering, brakes and wheel bearings.

The existing, non-power-assisted steering rack was knackered, so a new reconditioned unit was found and fitted along with all-new ball joints.

The brake calipers were brand new but 15 years old, so they were cleaned up and fitted with new rubbers and pads. The custom-made alloy suspension hubs had new bearings and ball joints installed, but it was the suspension A-arms that caused most problems.

Noble designed these using thin-wall tubing (1.5mm), and MIG welded the joints. While that’s all well and good in the UK, they would not be deemed as being compliant in New Zealand. As Brenden and Guy wanted to retain what Noble had designed, they asked Sheldon Carrington at Motorsport Developments in Granada North to replicate the front and rear arms. The resulting items passed all testing, so they moved onto the next challenge — sorting out the gear linkages.

With the driver sitting shoulder to shoulder with the passenger (for better centre weight distribution) there’s no room for a gear lever in the traditional place. Instead, it resides in the right-hand sill by the driver. However, the Porsche 914 transaxle was a side shift on the passenger’s side. Brenden spent many a night lying awake trying to visualize how this was going to work, without any success.

They went back to Sheldon Carrington, who took one look and told them to go up to the nearest Pick-A-Part and find a gear shift from a front-wheel-drive Toyota Corolla and bring him the whole thing, including the cables and gearbox shift mechanism.

Within a week he had modified the shifter and levers at the gearbox end to work, so all Brenden had to do was get the cable extended — brilliant! Sheldon then went on to custom build the whole exhaust system, including tuned-length headers to maximize flow and sound, along with the traditional four exit pipes as used by the original P4s. A balance pipe was added to make the engine’s signature more like two six-cylinder engines rather than the normal Porsche sound. The exhaust took Sheldon over 100 hours to design and construct, and though it was expensive, Brenden reckons it’s worth every cent as it sounds so good. So good, in fact, that they decided not to install a car stereo!

Final touches

As the car came together, an issue with the side doors materialized. The LVVTA wanted side-impact beams and door-retention systems to be installed. Brenden made a practical argument relating to where the occupants would sit in the car, and the impossibility of adding steel beams into a door that also housed massive air-intake tracts. LVVTA finally decided that the doors actually only have one purpose — to make the car waterproof — therefore no bars or retention systems were required.

The engine within the replica is a 2.7-litre flat six of 1974 vintage, fitted with a constant injection system (CIS). There’s no computer, as petrol is fed via the injectors constantly by a fuel distributor, a similar system as that used on many comparable engines during the ’70s and ’80s.

“I wanted old-school technology,” Brenden said, “No traction control or ABS, no power steering or airbags, no computers or automatic gearboxes. Back to raw driving pleasure.”

Despite the donor Porsche 2.7 engine having been rebuilt at some stage, Brenden replaced every seal and O-ring without pulling the heads off the barrels, as the motor had been sitting around for some years. New injectors, warm-up regulators and fuel pumps were also installed along with an air-conditioning compressor (not standard in New Zealand in 1974). The gearbox was pulled apart by Ruben Lithgow at Powerhaus (a Porsche specialist) of Wellington, and found to be completely worn out. The gears were fine, but everything else needed to be replaced — the appropriate replacement parts being sourced from the US.

When the Wellington-based Constructors Car Club announced that it would host a car show in October 2013, Brenden and Guy — both members of the club — made the call to have the P4 ready to display at the show.

The paperwork was sent to LVVTA for compliance and the certifier, Andy Smith, subsequently viewed the car and made a few minor recommendations.

In September 2013, the bodywork was stripped back to a bare shell and sent to Ben Martin at Custom Autoworx in Upper Hutt to prepare for final painting. Although the panels fitted pretty well, Ben spent two weeks to get everything as perfect as possible. Brenden’s brief was that the finished car should look like an original Ferrari when on the road — and that meant no big gaps between body panels, and a paint job that would stop traffic. This is the only P4 replica in New Zealand, and it needed a finish that would set a standard for any who chose to follow.

Chris Brattle at Dzine Signs (just across the road from Custom Autoworx in Upper Hutt) painted the car in Rosso Corsa, of course, and then added two coats of clear over the top.

Not because it was needed, but because Ben told Chris that Brenden would probably polish off the paint within a few years without a few coats of protective clear coat!

The fully painted car arrived back at Brenden’s home garage six weeks before the car show as a bare shell.

Show time

It would be fair to say that Brenden’s wife didn’t see much of him for the following weeks. Only four days before the show, Nick Tretheway from Mobile Upholstery started work on the P4’s interior — all in leather, with red double-stitching and diamond patterns on the side sills and door panels. Nick mentioned that the dash was the hardest he’d ever covered due to all its curves, and having to stretch the material in several directions.

He finished only hours before the transporter arrived to take the car to the show.

The Ferrari replica may have looked complete while it stood on display, but the wiring was rudimentary — with just enough wires fitted to allow the car to be started and driven. Indeed, the cable running from battery to starter was an extension cord! They didn’t even have time to put the side windows on — not that anyone who saw the car at the show twigged to that omission.

After the show, Peter Zhou from AJ Auto Electric Centre in Lower Hutt took five long weekends to wire up the car. Brenden and Guy then finished off a list of items, all minor, but ones that seemed to take ages to accomplish.

The car was corner weighed and found to have a 40/60 weight distribution with total weight of 980kg dry — a little heavier than the original, but that was the price paid for air-conditioning and a plush interior, and the replica’s front and rear fibreglass panels are actually quite thick and heavy, not the thin alloy used on the originals.

Finally, the car was booked into Andy Smith for the last compliance checks and transported to Levin and back. Having passed with flying colours, it was then taken down to the local VTNZ Testing Station for the WOF and registration.

As you’d expect, the wait was traumatic.

Brenden put it quite succinctly when he said, “Like an expectant father, I sat in reception at VTNZ for five hours while they did whatever it is they do. Expecting the worst, I had the car transporter’s number in my phone for the return trip — but it was not needed. Having passed, I then made the call to my insurer that I had dreamed of for the past four or five years, and through 6000 hours of labour. But with only 75mm ground clearance, first I had to get over the speed bump to exit the VTNZ facility!”

All that was left was a very careful drive home.

Brenden and Guy’s dedication and workmanship over the years has produced a vehicle far exceeding either of their expectations. Brenden’s were always very high, but he admits the final result still blows him away every time he opens his garage. Brenden has since brought Guy out of his share of the P4.

We’ll leave the final words to Brenden: “Like any newly built car, there will be minor modifications to come, but I can finally get out and share a replica of one of the rarest and sexiest cars ever made. Some of the highest praises have come from Ferrari owners who can’t believe the attention to detail and quality of finish (even though it lacks a Ferrari engine). To this I wish to thank all those who have either worked on her or provided their experience and advice. It could not have been done without you.”

1967 Replica 330 P4

- Engine: 1974 Porsche 911 flat-six

- Capacity: 2,687cc

- Bore/stroke: 90 x 70.4mm

- Valves: SOHC, two valves @ cylinder

- Comp Ratio: 8.0:1

- Max power: 112kW @ 5700rpm

- Fuel system: Bosch K-Jetronic CIS

- Transmission: Porsche 914 five-speed manual

- Suspension: F/R Double unequal length, wishbones, adjustable height, coil springs and 20-way adjustable telescopic shock absorbers

- Steering: Rack and pinion

- Brakes: Ventilated disc front, solid rears

- Wheels: F/R 9 x 16-inch alloy replicas all round

Dimensions

- Overall Length: 4330mm

- Width: 1870mm

- Height: 1040mm

- Wheelbase: 2480mm

- Kerb weight: 980kg

Performance

- Max speed: 270kph (on paper at 6700rpm in 5th gear)

Production

- Assembled: 1996

- Restoration: 2009–2014 (one of a kind)