data-animation-override>

“The Chevette was the last hurrah for Vauxhall in New Zealand, and was a better car than most people realized, as Donn Anderson recalls”

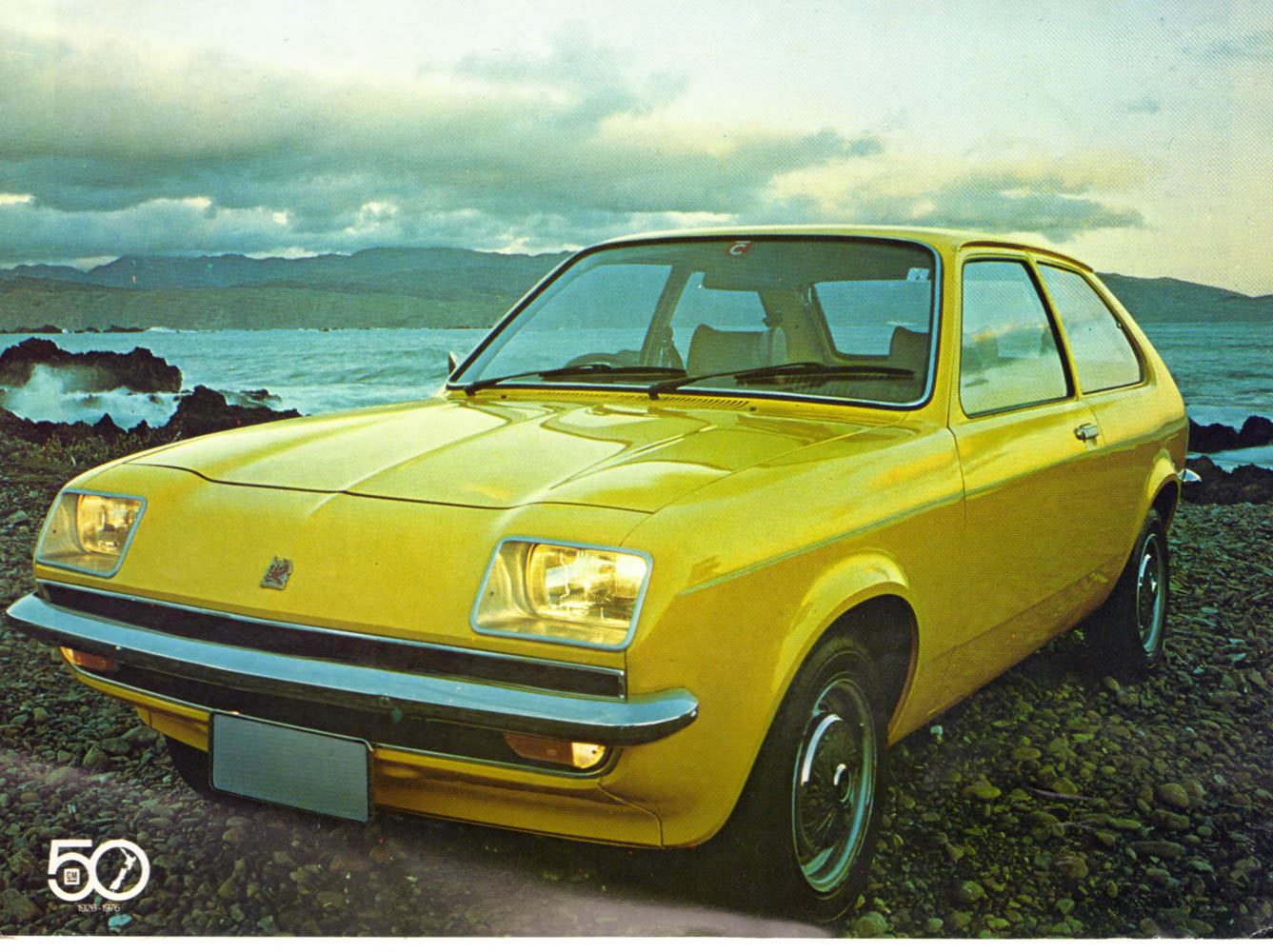

You know an advertising agency has done its job when four decades later the theme song for a product still runs through your mind. The location was a West End theatre in London in March 1975, and Vauxhall was launching its trendy new Chevette three-door hatchback.

I had been invited to the colourful knees-up unveiling, dominated by the song, The Vauxhall Chevette is whatever you want it to be. General Motors (GM) would use the song as background to the UK television commercials and today, 40 years later, I still relate the car to the music.

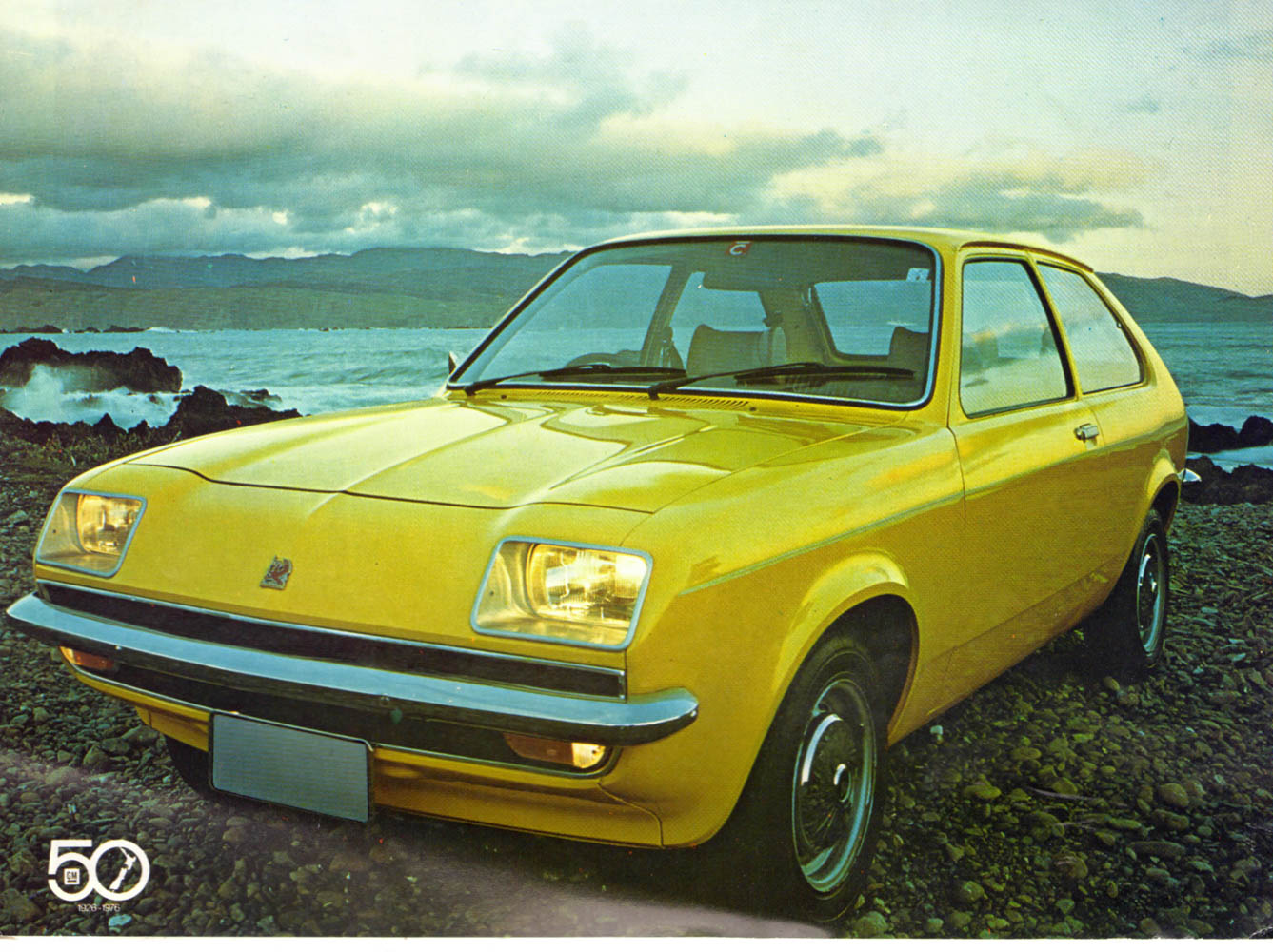

So, where have all the Chevettes gone? GM built around 10,000 of them at the Trentham plant in the Hutt Valley north of Wellington over a five-year period, but most have disappeared. The Chevette was the last British sourced, Vauxhall-badged car to be assembled in New Zealand, and it was a significant vehicle in more ways than one.

Small car challenger

This new Chevette was also a good deal better than most people realized. Introduced as a hatchback measuring just 3944mm, the rear-driven ‘super mini’ would later evolve into a four-door sedan and three-door station wagon. Shorter than the Vauxhall Viva that had been the marque’s best local seller, the Chevette was part of the GM line-up until 1977.

The Chevette was also one of GM’s T-platform world cars, based on the 1973 German Opel Kadett. Other ‘T’ cars included the Australian Holden Gemini, Japanese Isuzu Gemini, North American Chevrolet Chevette, and the South American Pontiac Acadian.

GM New Zealand badly needed the Chevette to counter the growing mass of small Japanese cars. The brand had seen its local market share dwindle from an industry-leading 23.6 per cent in 1972, to less than 10 per cent four years later. The Chevette’s Kiwi launch in October 1976 coincided with 50 years of GM operations in New Zealand, and the following year a locally assembled notchback sedan became available. Station wagon and van variants further widened the Chevette line-up, but it was always the hatch that the market perceived as the iconic model. An automatic option was added to the GM’s 1980 CKD programme.

During the early years the car was usually in the top-10-model sales list, and in the late ’70s GM was doing close to 100 Chevettes a week for the 100-strong New Zealand dealer network. The General’s new baby was eighth most popular car in 1978 with sales of 2475, while 1979 was the car’s best year, with 2653 sales in a larger overall market, dropping the Chevette to 10th-best-selling new car in New Zealand.

Initially, the Vauxhall outsold rivals like the Honda Civic and the Datsun Sunny, but by 1979 the Corolla, Escort, Mirage, and Civic were all doing better.

Having launched with a retail of $5495, the Chevette’s price rose to $6590 in 1979, and $7465 with the arrival of the facelifted version in mid 1980. This revised version had flush-fitting headlights, stripes, better seats, improved ventilation, and sports wheels — but the changes were not enough to combat the opposition. Even though it was still the lowest-priced hatchback in New Zealand, sales dropped to 1409, relegating the car to 19th on the best-sellers list, while rivals Corolla (5135 sales), Mirage (5432), and Civic (4419) were making life difficult for the Vauxhall.

Chevette’s final year of CKD assembly in New Zealand came in 1981, with production ending in June, and the car rounding out the year with 791 sales. The last of the three-door GL models retailed for $8545.

Driver’s car

Across the Tasman, Holden was promoting its Radial Tuned Suspension (RTS), and New Zealand decided to adopt these modifications to the locally built Chevette. By then 175/70 series rubber on wider wheels had replaced the original 155 by 13-inch radial-ply tyres and this, plus suspension adjustments, made the New Zealand Chevettes unique, and further improved what was already a fine-handling car.

GM promoted the Chevette as “a real driver’s car” in 1980, and it was right.

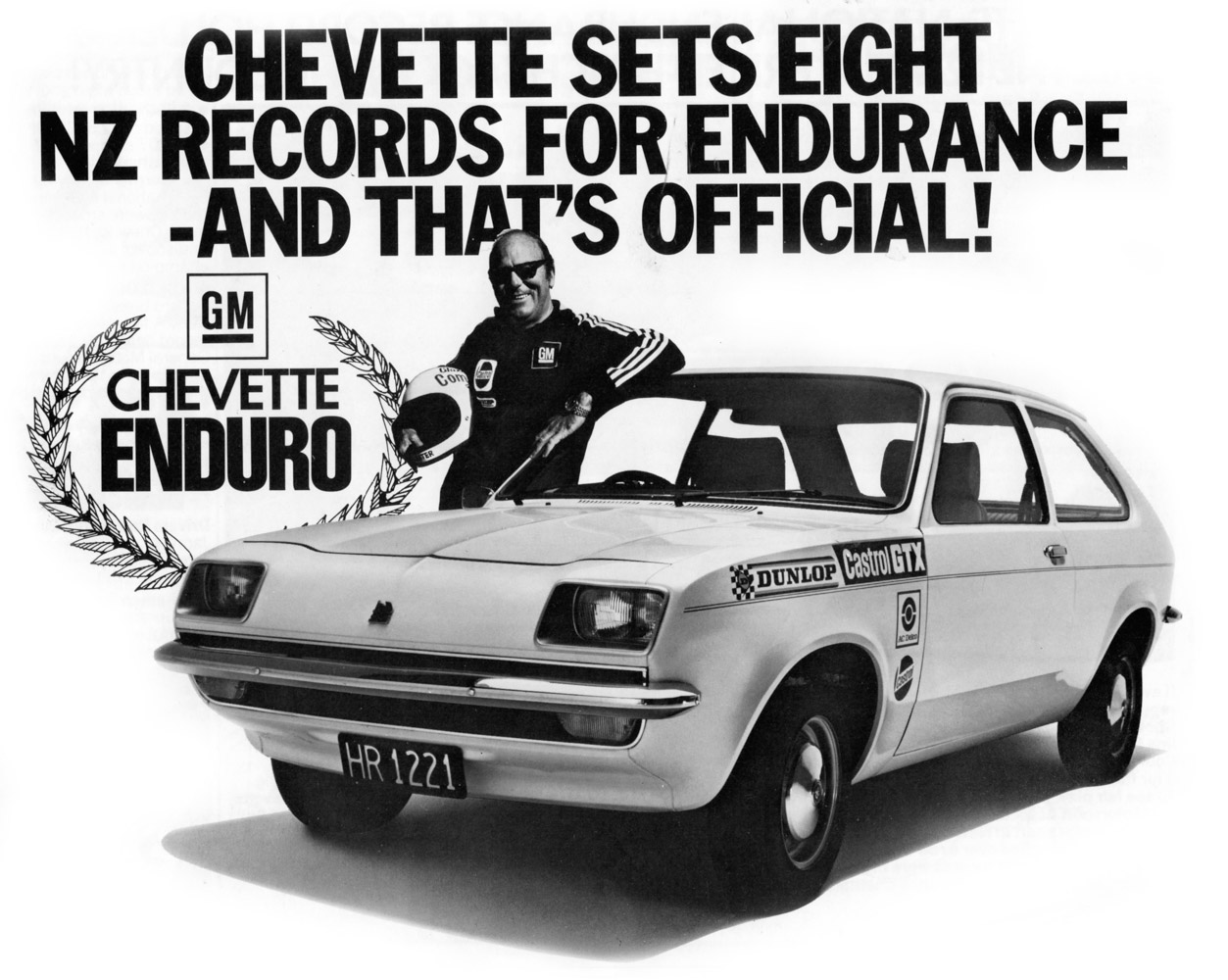

Former world champion Denny Hulme came on board to promote the car, and a Chevette ended up in his personal garage alongside the family Range Rover and Jaguar XJ6. Hulme had high regard for GM products, having raced a German Opel Commodore with success in the 1976 Tour of Britain, and of course, he would go on to race Holden Commodores.

Selling the Chevette

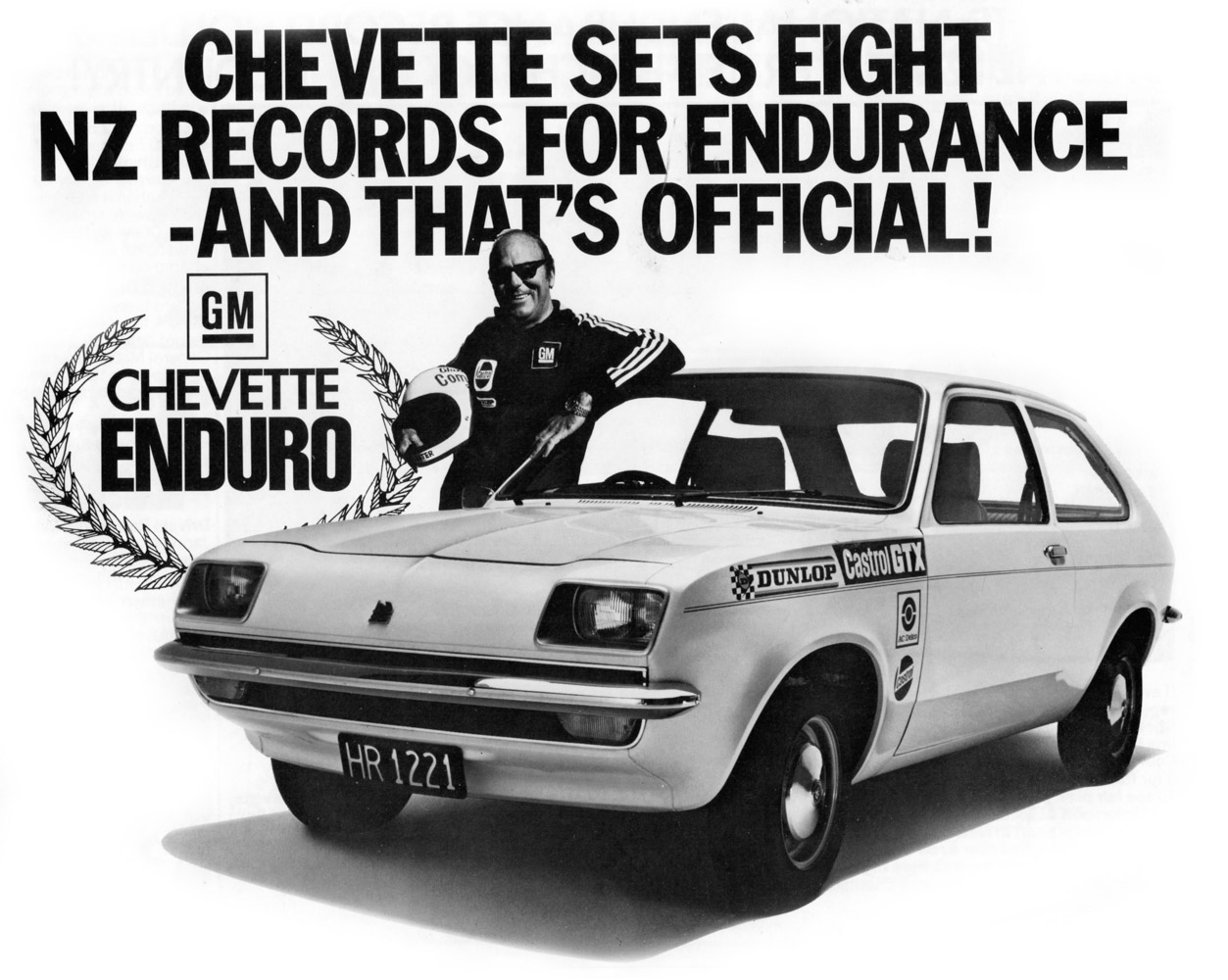

GM New Zealand worked hard promoting its smallest car in the late ’70s, and conducted a five-day endurance record at the Manfeild race track with a standard Chevette. Rob Lester, Peter Jarratt, and Norm Lankshear drove in six-hour shifts, packing 11,107 kilometres into the drive and establishing eight New Zealand records. The car covered 3666 laps at an average speed of 92.566kph, stopping only for fuel and oil.

GM then advertised the car as the Chevette Enduro, and ran one in the Mobil Economy Run in which it emerged a class winner, with an average of 6.14 litres/100km (46 mpg). A Chevette established another New Zealand record by driving backwards for 695 kilometres over 29 hours for a charity promotion.

The Chevette was also making its mark in motorsport, and in Britain the factory produced 400 HS versions, powered by a 2.3-litre, twin overhead camshaft, 100kW (134bhp) engine, a five-speed Getrag gearbox plus uprated suspension and a body kit. It was hugely successful, often beating Ford’s Escort RS2000, and winning the British open rally championships in 1979 and 1981. Locally, a pair of GM Dealer Team Chevette 2300s were entered in major rallies for Paul Adams and Shane Murland, with Adams finishing second in the 1981 national rally championship.

On test

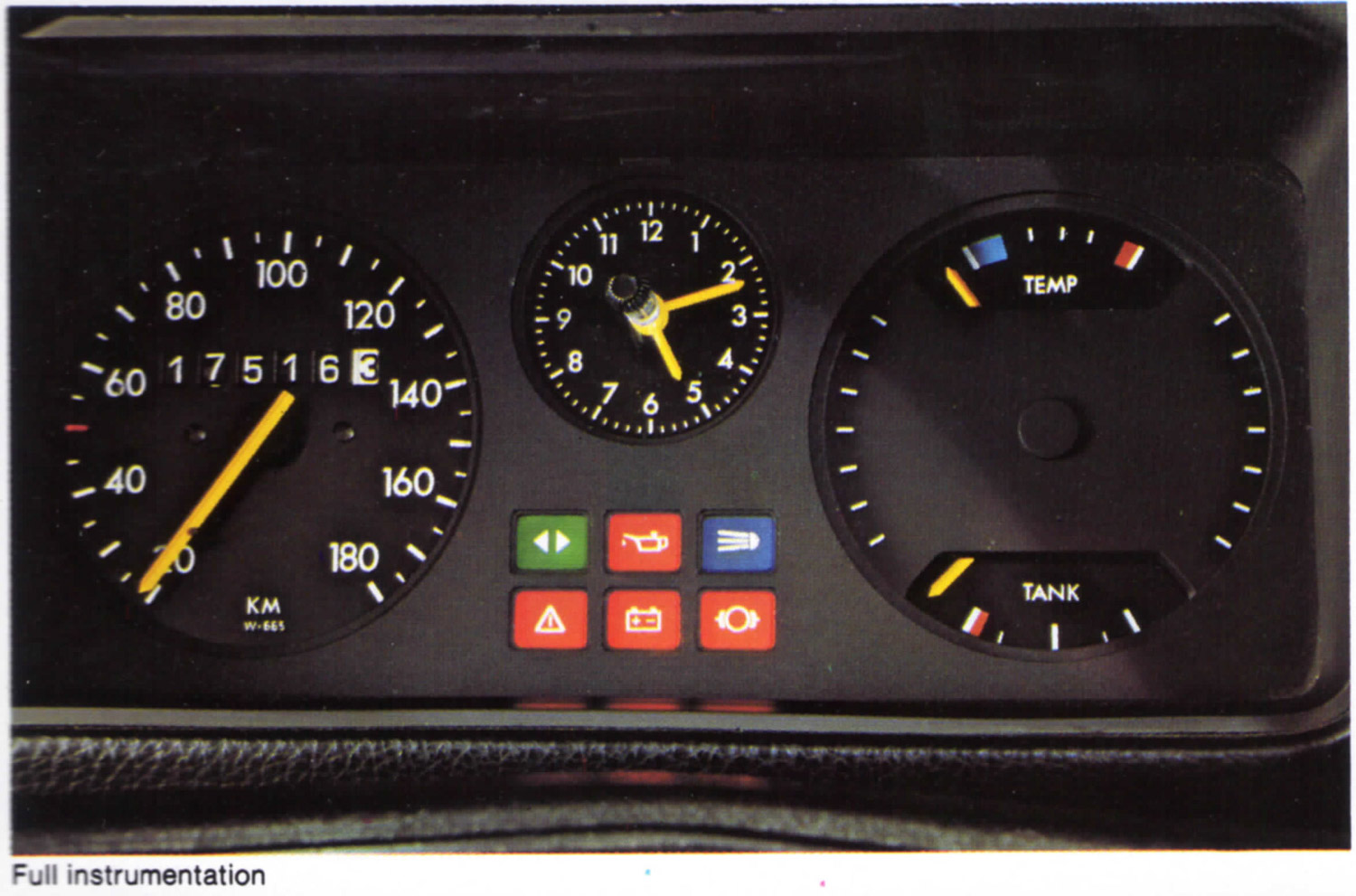

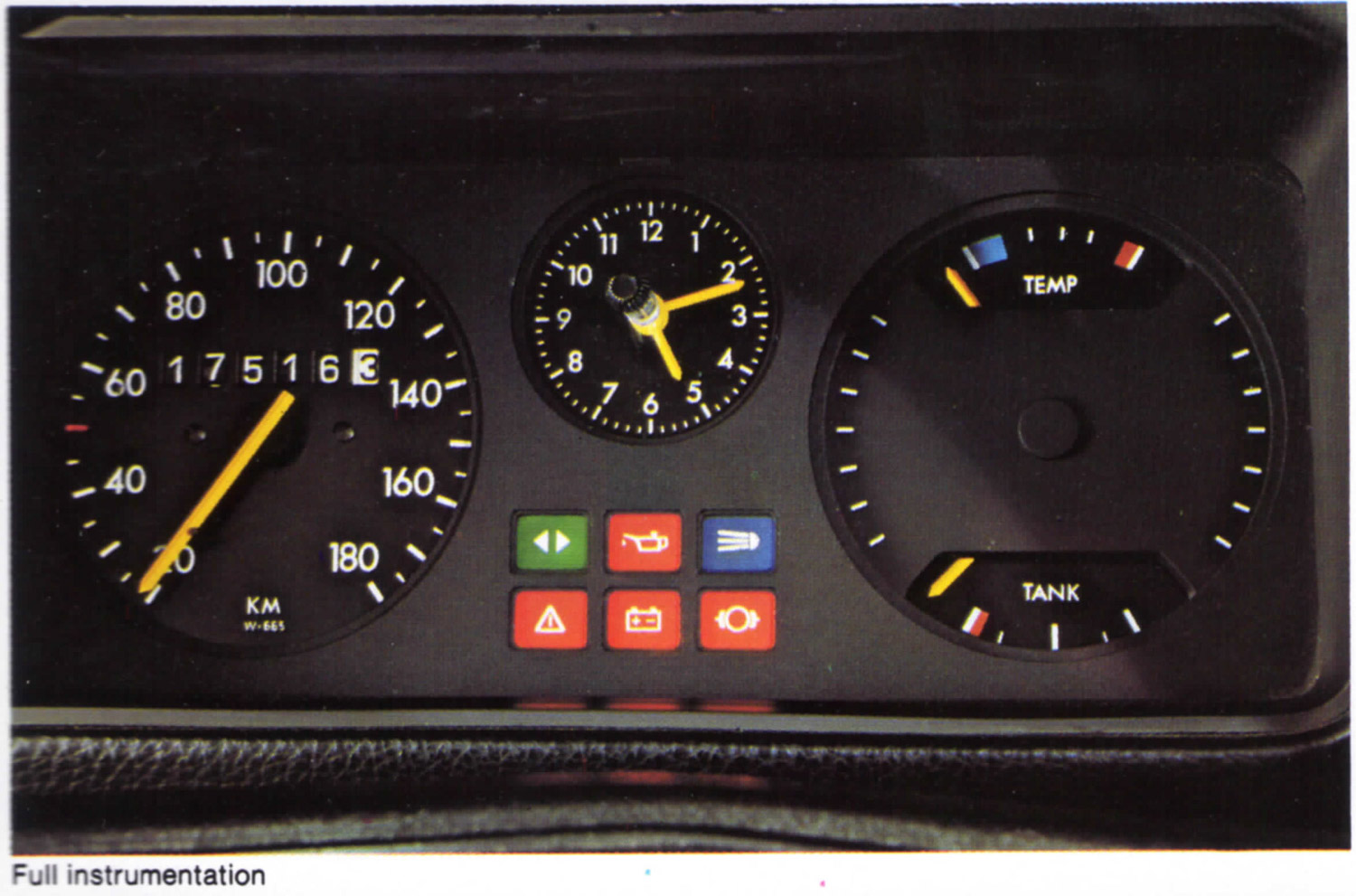

On paper the mainstream Chevette looks relatively mundane, with the Viva-derived 1256cc, pushrod overhead-valve iron-block engine producing a modest 43kW (58bhp), peak torque at a low 2600rpm, and riding on a live rear axle with trailing arms and Panhard rod. But this car is, indeed, more than a sum of its parts, offering outstanding roadholding, good fuel economy, and a degree of refinement hitherto absent from smaller Vauxhalls.

A few weeks after that London party, I spent a day putting in an intensive 400km of driving on English roads, and came away with the impression there were few small cars more quiet at 115kph than the Chevette in 1975.

As some critics wrote, with the vast improvement in refinement it was difficult to believe that this was the same engine fitted to the Viva. This was the measure of well-designed engine mountings and better noise insulation. Of course the car was no fireball, but the zero to 100kph time of 14.5 seconds was well up to class standards.

In company with two other Chevettes on the M1 motorway in all types of weather, the Vauxhall revealed the effectiveness of its styling, with the rear window staying clean without the aid of a wiper. Straight-line performance was on par with 1300cc rivals, but we had no difficulty holding 145kph (90mph) for long periods, with little intrusion of wind, road or mechanical noise. It was this aspect that also impressed Hulme, who thought nothing of driving his Chevette from one end of the North Island to the other.

The car was a multi-national effort encompassing British and German input, and despite being around 20kg heavier than the Viva, it was 15 per cent more economical. Engineers were able to extract better economy by fitting a temperature-controlled air cleaner to the Stromberg CD carburettor. There was a further four per cent improvement in economy with the facelifted 1980 model. Apart from a large gap between second and third gears, the ratios were well chosen, but the gearbox was sometimes a little notchy and obstructive. The car’s flexibility in both urban and open-road conditions was excellent, and the 146kph top speed was good for the class of the day.

No complaints, either, about the rack-and-pinion steering — light and precise — or the tight turning circle. The car’s roadholding and handling bettered the Kadett equivalent because of less rear body overhang and better weight distribution. In my original road test I commented about the good steering feel, lack of body roll and mild understeer when pressing on, as well as the predictability and fine balance in wet conditions. “There is never any sudden loss of grip or control, and even if the driver backs off while negotiating a corner at high speed the understeer will change only gradually to oversteer. A very safe car and great fun to drive, while crosswinds have little effect.”

Some sort of compromise had to be reached with the suspension, and while the handling and roadholding could not be faulted, the car’s ride tended to be harsh and a little bouncy on all but the smoothest of roads. Front disc/rear drum braking was powerful and progressive.

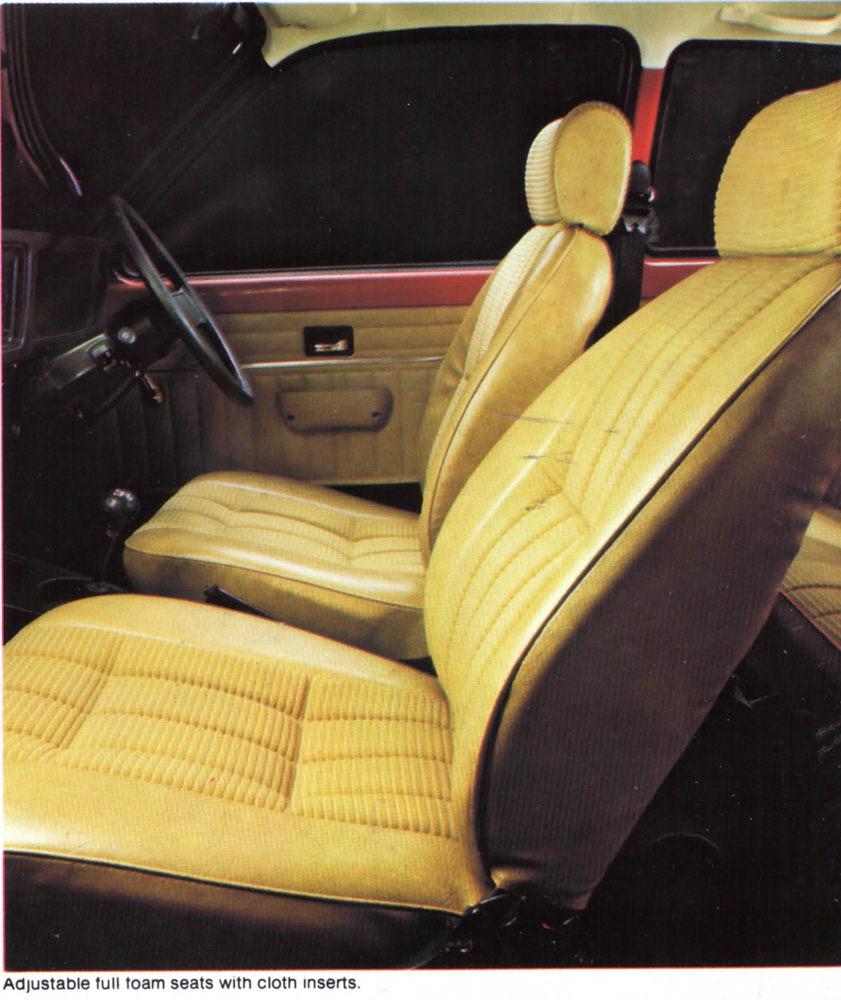

Rear seat legroom was a limiting factor, but the driving position was good, although the brake pedal was too high and legroom inadequate for tall drivers. The German Opel-designed seats were well shaped, but in facelift models the front seat backs were carved out to gain some much-needed space for rear-seat passengers.

Britain’s first hatchback

The Chevette broke ground for usually conservative Vauxhall at a time when hatchbacks were thin on the ground. This was the first British hatchback, a year ahead of the Ford Fiesta, and predating Leyland’s Mini Metro by five years. Vauxhall sold 415,000 Chevettes in the UK, and New Zealand joined Ecuador and Uruguay as the only three export markets assembling the model. Local build standards were up to mid ’70s levels — that means, not very good. The Chevette estate I evaluated on local roads in 1980 had poor paintwork and doors that needed slamming, unlike the UK-built equivalents that were much better built.

While the car was mechanically similar to the Kadett, there was no doubt designer Wayne Cherry produced a better-looking model with its droop-snoot nose and tidy rear-end styling. American-born Cherry came with impressive credentials as a member of the design team on the original Camaro and Pontiac Firebird and the 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado. Cherry, whose personal cars included a Ferrari and an elderly Rolls-Royce, always wanted the Chevette to have a sporty look, and in the ’80s he was still driving a specially modified example as his daily driver — a 2300 HS fitted with F1-style side skirts and a deep air dam.

Seven years after the arrival of the Chevette, Cherry reckoned the car was standing the test of time. “It’s a fairly simple design but I am still very pleased with it,” he said. “The styling hasn’t dated much, the engineering and the integrity of the car are good. In a way it’s a classic — just a nice, super little car. If we were doing it over I don’t think we would do it any differently.”

Having been seconded to Vauxhall in the UK during 1965 for what was intended to be a temporary assignment, Cherry ended up working in Europe for 26 years, becoming responsible for the design of all GM European passenger cars. He went on to become GM vice president of design at head office before retiring in 2004.

Chevettes are simple, reliable cars and are easy to work on, with features like bolt-on front guards and easy access in the roomy engine bay. The wonder of it all today is their scarcity on our used-car market. Good examples fetch around $4000, while the rare, be-spoilered 2300 HS commands high prices in the UK. The most likely problem will be rust around the sharp edges of the nose.

The Chevette’s timeless styling makes it one of the better British cars from the ’70s, and it probably should have done better in New Zealand. It was, perhaps, initially living in the shadow of the Viva, or was seen by consumers as a last relic before GM NZ switched from Vauxhall to Holden. Either way, it was a very good car, more deserving of a bigger impact on our market.

You can buy a copy of the magazine that this article first appeared in below: