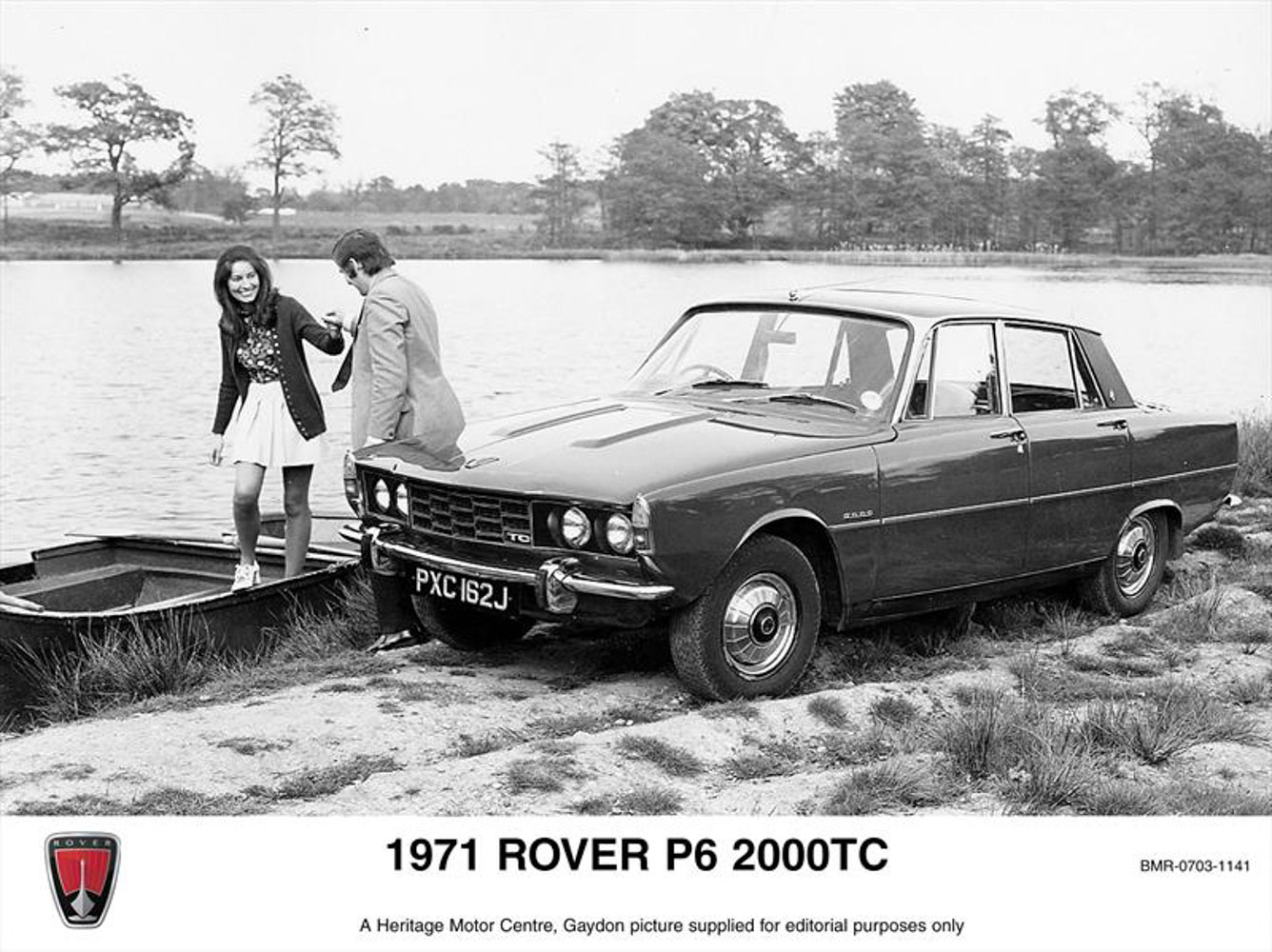

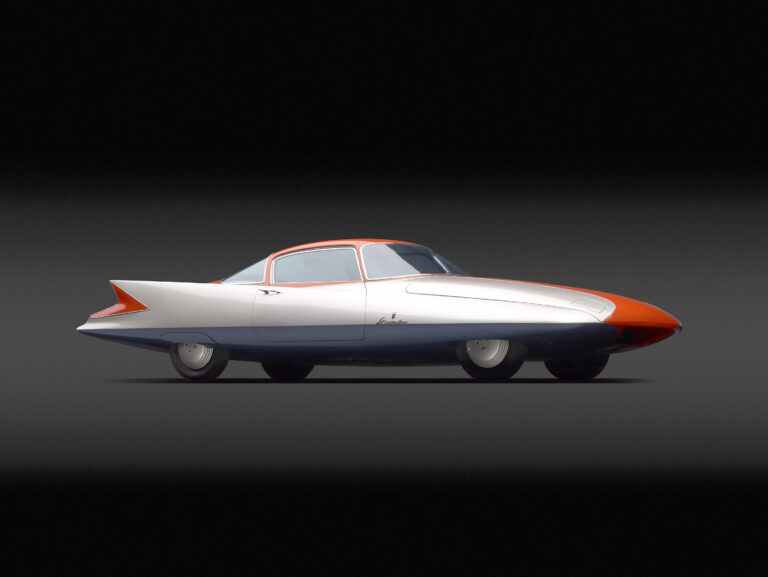

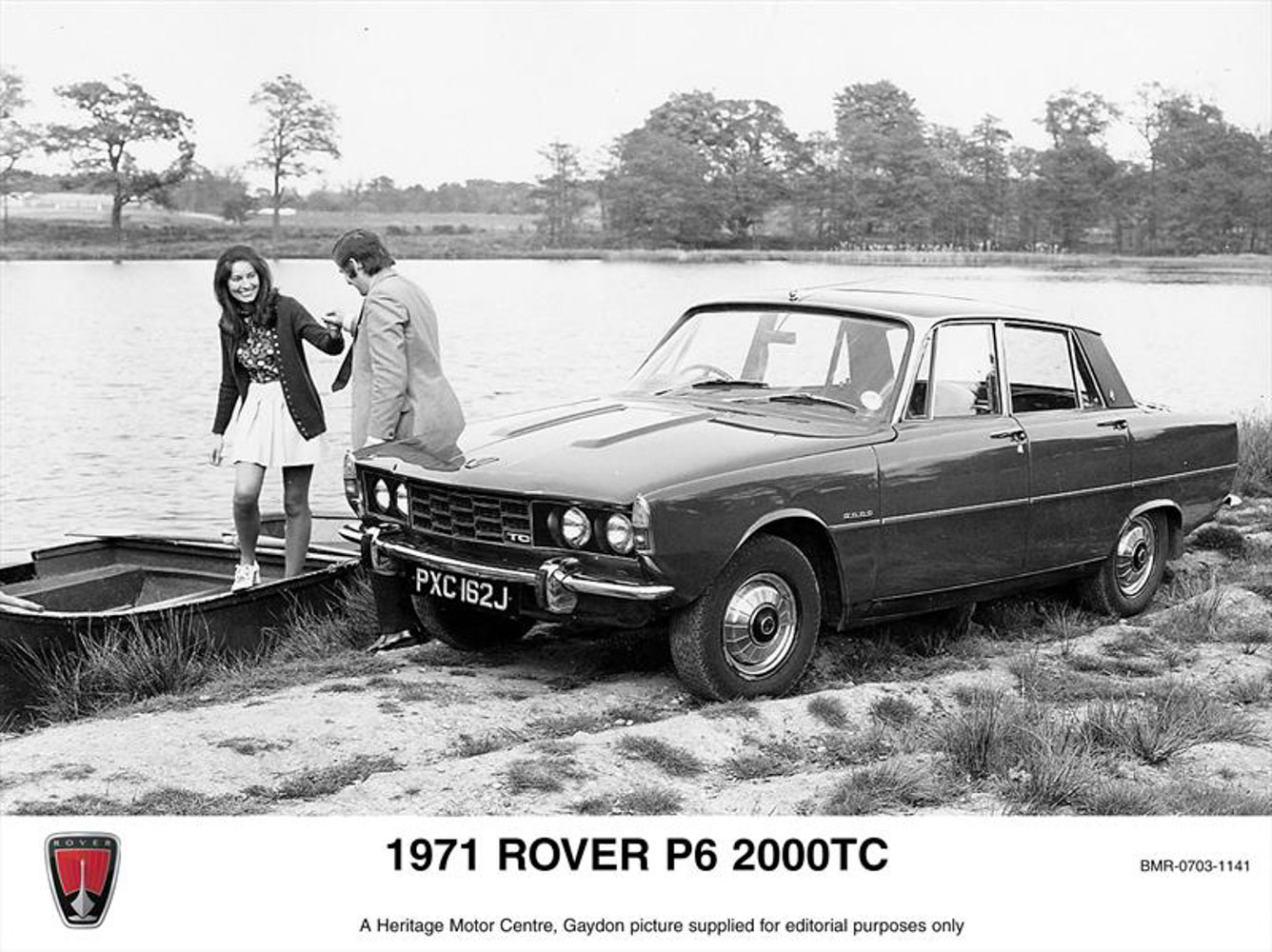

With the launch of the first P6 in 1963, named as such because it was Rover’s sixth post-war model, Rover made their first indication that the company was now after the new ‘young executive’ market, who were looking for more sporting pretensions in their saloon cars. Previously noted for the production of, well ‘traditional’ cars, the P6 featured crisply distinctive, and very modern lines, secured via a steel base-unit onto which the panels were bolted. Although Rover had first considered this method of construction as early as 1953, Citröen had already released their D-series cars featuring similar body construction by the time the P6 was launched. Indeed, the original David Bache-penned P6 styling models showed some outward resemblance to the Citröen, especially with its sloping nose and rear tail fins. However, the fins were quickly deleted whilst the sloping nose was sliced off and replaced by a bluffer, more conventional front-end.

The P6’s suspension was also notable, with its rear de Dion tube and Watts linkage. The front also utilized an unorthodox set-up, whereby top links pivoted from the top of the coil springs which, in turn, acted against the front bulkhead — this gave the P6 an unusually wide engine bay. The extra space had been specifically designed to take Rover’s gas-turbine engine, but this unit never went into production.

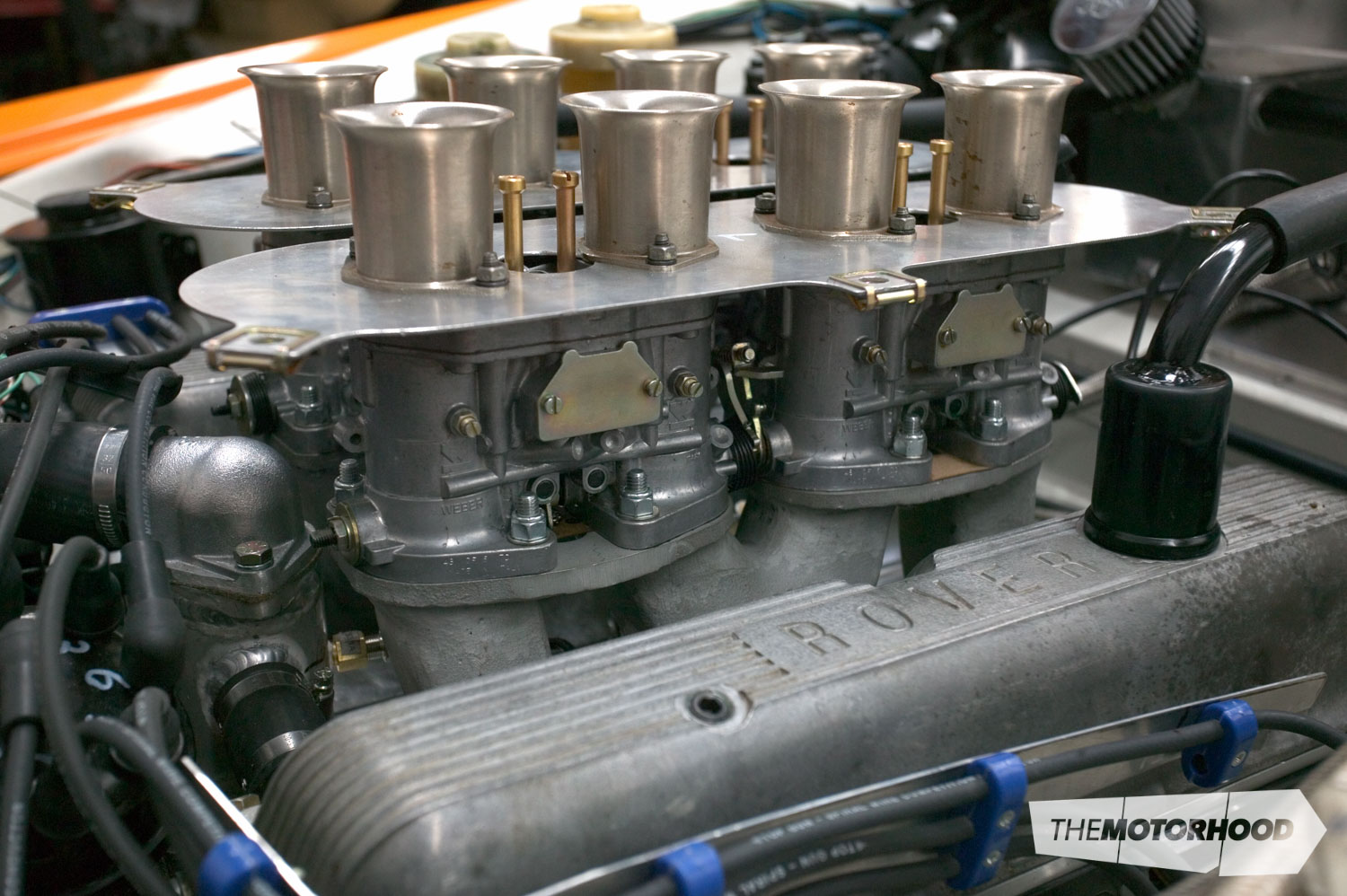

Although the 2000TC gave improved power over the 2000SC, Rover, and contemporary road-testers, soon realised that the P6’s excellent chassis could handle considerably more power and, as the proposed gas turbine engine was some way off, Rover began to consider other options. Initially a six-cylinder version of the 1978cc four-cylinder engine was considered. Several prototypes were made and the new three-litre six was speed-tested up to 143mph. But the six was both heavy and very long, causing major changes to the P6’s body. A cheaper, 2472cc five-cylinder was proposed by Peter Wilks, Rover’s Chief Engineer, and several prototypes were produced. But finally, after all the trouble, all of these options were abandoned when Rover’s MD, William Martin-Hurst, returned from a US trip with the 3.5-litre Buick V8.

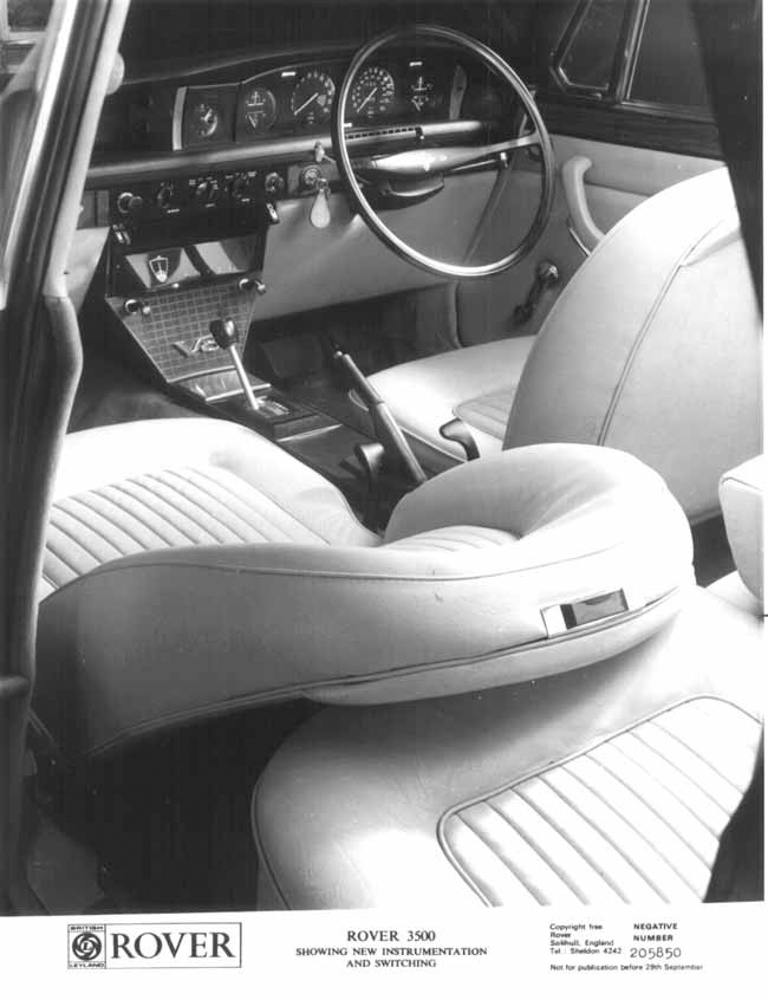

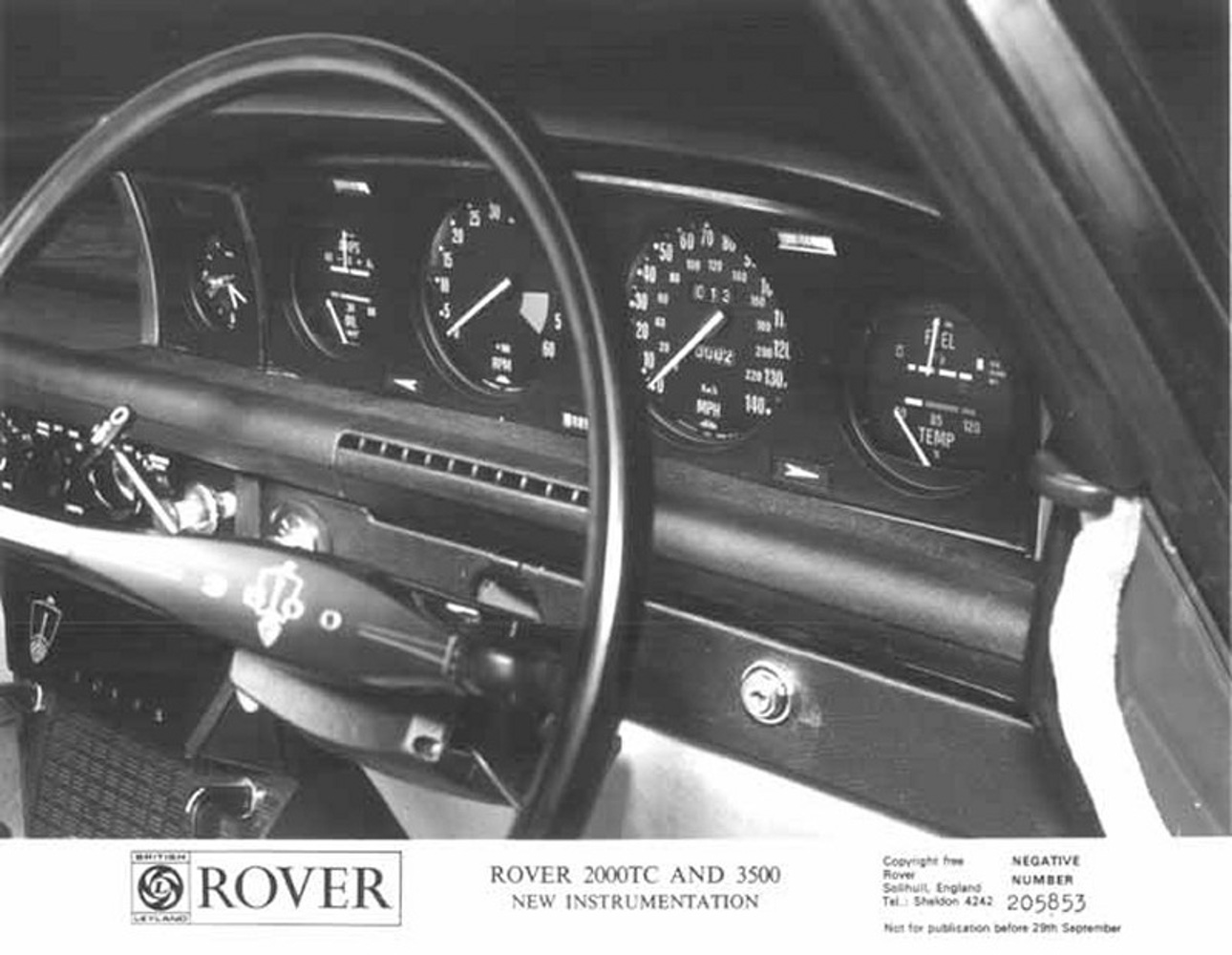

Initially trialled in the P5B in 1967, the ex-Buick V8 was shoe-horned into the P6 body in 1968 for the 3500 – and one of Britain’s best-loved sports saloons was born. Eventually replaced in 1976 by the disappointing SD1, the 3500 — and especially the 3500S — are now very popular classic saloons, combining easy cruising from the light-alloy V8, excellent handling, and, of course, traditional Rover values.

New Zealand Classic Car prime pick: P6B 3500S

While there is little doubt that the 2000/2200TC cars offer adequate performance, there is little to match the feeling of driving a well-sorted V8. Of these the 3500S, the beloved choice of the UK motorway police during the period, is the pick of the crop — although the four-speed manual can be notchy in use, and under pressure from the V8’s torque it is not renowned for its longevity. Additionally, there are many Rover specialists in New Zealand who can literally transform both the handling and the performance of the 3500, capable of tastefully mutating the P6 into anything from a refined grande routier to a fire-breathing road-burner.

Buyer’s spot check

The big advantage that the Rover P6 has over most of its contemporaries is the nature of its body construction. As external panels — including sills and roof — are simply bolted into place, replacement of damaged or rusted panels is simply a matter of wielding a spanner. As such, exterior rust is less of a problem than in a traditional unitary-constructed car. However it is the rust you can’t see that is the bigger danger. Put simply, if a P6’s exterior panels exhibit massive signs of rust (most notably present on the door bottoms, sills, and the bottom of the rear door jambs), expect to find more corrosion on the chassis and body superstructure. The only way to really check this out properly is, of course, to remove all the bolt-on panels – or to ask a specialist to check the car out.

Areas that can be more easily checked include the air-space beneath the panel at the bottom of the rear screen. Accessible from the boot, this space usually fills with debris and can quickly rust out, reducing the efficiency of the boot seal. This is turn will lead to rust around the boot floor and battery box. Most serious rust problems in the P6 will be found around the rear of the car, so it pays to check out this area carefully.

Mechanically the V8 is a better bet than the two or 2.2-litre engines, principally because spares supply is so much better for the light-alloy V8. Parts are in shorter supply for the four-cylinder engines, and buyers of these should check for noisy tappets and timing chains, because eliminating either problem can be expensive — even tappet adjustment carries a sizeable labour component in order to partially strip down the engine. By comparison top end overhaul of the V8 is a far easier task, although it can still be expensive. The V8 has no real weaknesses but is renowned for wearing out camshafts.

Automatic gearboxes should give little trouble, but worn manual ‘boxes will normally exhibit excessive noisiness, and are known to jump out of reverse. Clonks in the driveline will usually mean worn rear universals and suspension clunks are a good indication that suspension bushes are worn — most specialists recommend fitting nolathane bushes to combat this and tighten up the P6’s handling. Finally it pays to check the condition of the de Dion tube, as these can often be bent by careless mechanics who have used the de Dion as a jacking point.