data-animation-override>

“In 1966 Kiwis scored a one–two finish at Le Mans. In 2015, local lads Earl Bamber and Brendon Hartley followed in the footsteps of Chris Amon, Bruce McLaren, and Denny Hulme”

The 2014 big adventure to the 24 Hours of Le Mans was special in that New Zealand had a driver in the top LMP1 category for the first time in many years. To add a bit of spice to the event, it also marked Porsche’s return to sports car racing’s blue riband event after a 16-year hiatus.

Kiwi Brendon Hartley (25) had been snapped up at the beginning of 2014 as a full-time works driver for the German manufacturer in their brand-new, high-tech 919 Hybrid. In the run up to the race, it was bloody exciting to think that a New Zealander — along with teammates Australian Mark Webber and German Timo Bernhard — might be in with a chance of a podium finish.

In all honesty, the chance of getting Hartley to the top spot was going to be a big ask in a car that had only been in a few races prior to the Grand Prix of endurance or efficiency. However, with two-and-a-half hours to go, there was a palpable sense of hope and expectation in the Porsche camp, as Hartley and company were in front — then reality set in. The car rolled to a stop with a disappointed Webber gripping the steering wheel in immense frustration, having failed to finish yet another 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

At this point, I would like to quote something I said in last year’s piece on the race: “Porsche will be back next year. There’s no doubt about that, and probably with a third car. They have a determination to get back to their previous winning ways. And, with another year of development and testing of the 919, who’s to say trophy number 17 won’t be winging its way back to Stuttgart in 2015.” Well, there you go.

Kiwi triumph

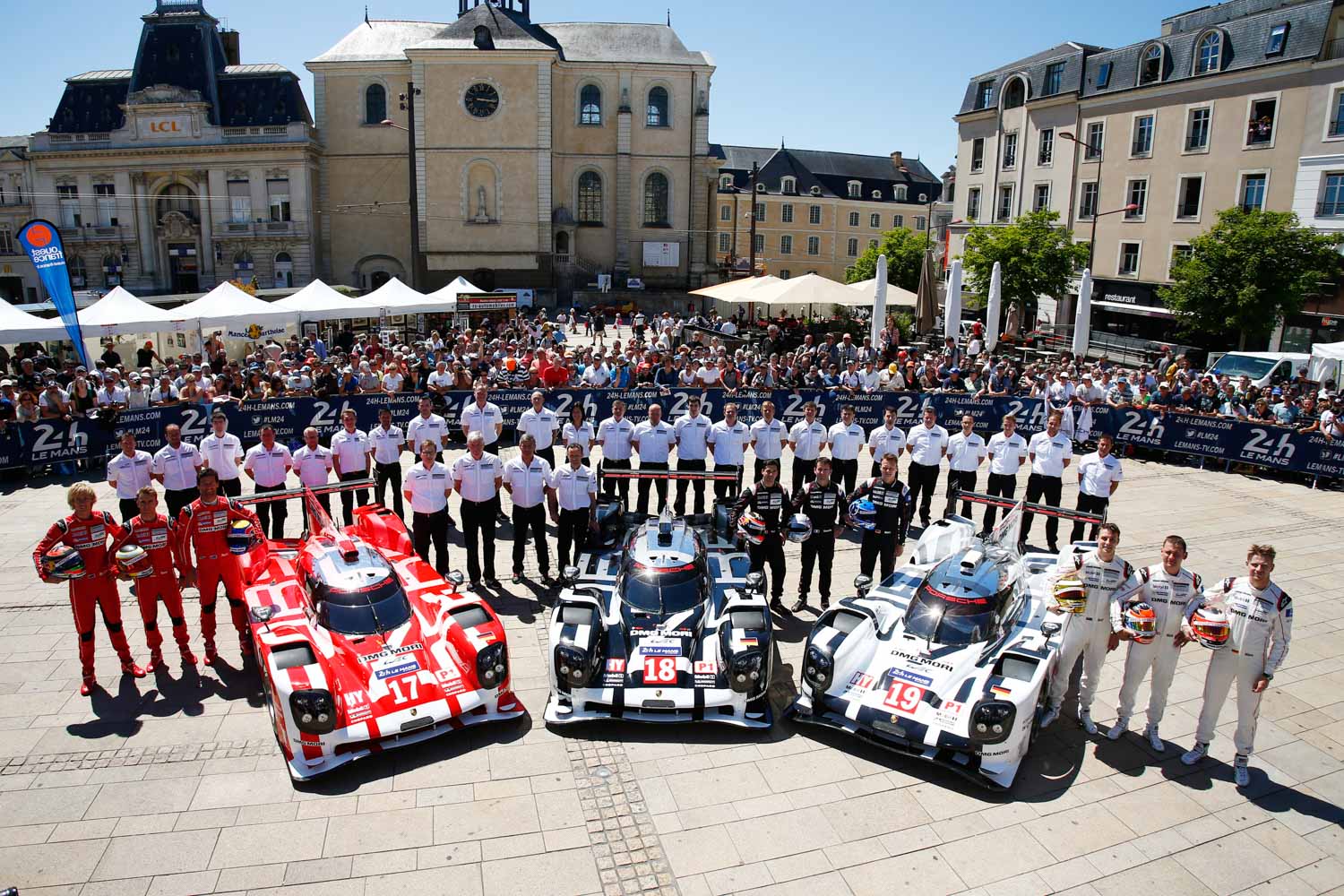

This year was a completely different kettle of fish on a number of levels. Audi, Toyota, and Porsche had three cars apiece. Nissan had rejoined the LMP1 fray with a odd-looking front-wheel drive thing, and New Zealand had four — that’s right, four — drivers in the 83rd running of the oldest and most spectacular long-distance race in the world.

Joining Hartley in a third 919 Hybrid was Earl Bamber (24), who had also been locked into the Porsche family as a works racer. His main focus is campaigning a 911 RSR in the American United SportsCar Championship, but he was called upon to take part in the Le Mans race, joining German Formula One pilot, Nico Hülkenberg, and British racer, Nick Tandy.

If that wasn’t good enough, Aston Martin Racing decided to run Richie Stanaway (for a full World Endurance Championship season) in the LM GTE Pro class, alongside Alex MacDowell and Fernando Rees. Finally, GP2 combatant Mitch Evans featured in the Jota Sport’s — the defending champion — LMP2 car with Brits Simon Dolan and Oliver Turvey.

As anyone with even a passing interest in motorsport will be well aware by now, three of the four Kiwis in the field stood on the podium 24 hours after the starting lights went out. Rookie Bamber won from Hartley, Evans finished second, and Stanaway was robbed of a win by his co-driver Rees, who T-boned an LMP2 car in the morning of the second day’s racing.

It’s fantastic that after 49 years, two Kiwis have emulated the exploits of Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren, who won from fellow Kiwi Denny Hulme in that historic Ford GT40 Mk.II one–two finish.

For me, though, the best part of the weekend was being able to sit next to Sir Colin Giltrap with less than two hours to go on Sunday afternoon, and see two New Zealand names at the top of the leaderboard. Bamber, Hartley, and Evans are all protégés of Sir Colin, and his investment of faith, time, and money came to fruition at 3pm French time.

To see Sir Colin smile — let alone display much more emotion — is an extraordinarily rare thing. His evident joy lit the pavilion up, and he looked like a small boy who’d just been given the keys to a sweet shop.

“Isn’t that great seeing those names at the top of the board,” said Sir Colin, “It’s very good to see young talented New Zealanders doing well here at the 24 Hour.”

Tears in their eyes

Sir Colin is one of New Zealand’s greatest investors in Kiwi motorsport talent, and has a canny knack of spotting the good ones early in their career. He’s your archetypical old-school Kiwi bloke who likes to help others, but wants to fly so far under the radar that he scares moles.

The fantastic thing over race weekend was seeing him with a spring in his step after his boys had done him proud, with all three getting on the podium.

And, speaking of the Kiwi triumphant, the Australasian media contingent was at a round table with Dr. Frank-Steffen Walliser, the head of Porsche Motorsport, the day before the race. I asked him about the number of New Zealand drivers in the team, to which he replied, “It is amazing how many drivers from New Zealand are racing internationally, and here at Le Mans, with so much success. It’s certainly interesting — there must be something going on.”

Being able to attend the event meant you could observe close-up and in detail the emotions on everyone’s faces, without a television director making arbitrary decisions about what you can and cannot see on the TV screen. The reaction of the three drivers who won the race couldn’t have been more different if you’d planned it.

Tandy was in tears, Hülkenberg was looking around as if he’d lost something, and then you had Bamber. The Kiwi had an open-mouthed grin big enough to fit his race car into, and didn’t seem to know where to look as he punched the air so much, that even the gods must have felt a little sore.

I spoke to Bamber after his stint at around 1am on Sunday, and he was relaxed and in a good frame of mind. Post-race, he wasn’t so calm, and you wouldn’t really expect him to be — especially after winning Le Mans at his first go, and just 24 years old.

“Yeah — we won this thing. I mean, I still can’t believe we did it,” said Bamber, as his head pivoted from side to side, taking it all in. “The car ran perfectly all race long. We were quick, never had to go into the garage at any time, and bought the car home without a scratch on it.”

Bamber and company were the jokers in the Porsche three-car pack, having only driven the car once together before, at Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps. The idea was they were to ‘play the hare to the hounds’ and go flat out for as long as they could. In doing so, they would run the Audis and Toyotas into the ground, leaving the way open for the remaining 919s to battle it out towards the end.

Well, it didn’t quite work out that way. The LMP1 Le Mans rookies took the day, the race, and the mother of all trophies. In the press room, I was asked a few times if Chris Amon would be miffed after losing the record as being the only Kiwi to have won Le Mans. I said no, as I was certain the old boy would be dead chuffed another young Kiwi had taken up the challenge and put everyone to the sword. And anyway, Amon will always be known as the first, and the youngest, Kiwi to win the great race — he was 22 years old when he crossed the line first, so owning two of the trifecta can’t be all bad.

Indeed, in conversation with Chris after the race, he said “I was very pleased and happy for Earl that he won Le Mans. It doesn’t bother me in the least that my record has been broken, it’s been a long while since a Kiwi’s been on top in the race. I was mentally prepared for them winning, but didn’t anticipate another one finishing second. It was a brilliant result, and I was really delighted to see it happen, especially with Mitch doing so well, as well.”

Back in the pavilion an hour or so after the race, two of the heads of the 919 programme were in tears and hugging each other. I’m unsure if they were for the joy of winning, or because they’d be getting a fat bonus and keeping their jobs. Last year, the pressure for them to win was pretty big, but this time around it must have been like having Ayers Rock balanced on both shoulders.

Bloody fantastic!

On the flight over to France, I got to thinking that, having experienced the race last year, I might be a bit jaded this time around. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The only difference was that I — sort of — knew where I was going when heading off for a wander, and could find my way back rather more easily than the last time I was at Le Mans.

There is definitely an emotional element about going to Le Mans — it’s deep into the night, in particular, when the real ethereal beauty of those howling, speeding beasts takes on an almost otherworldly quality.

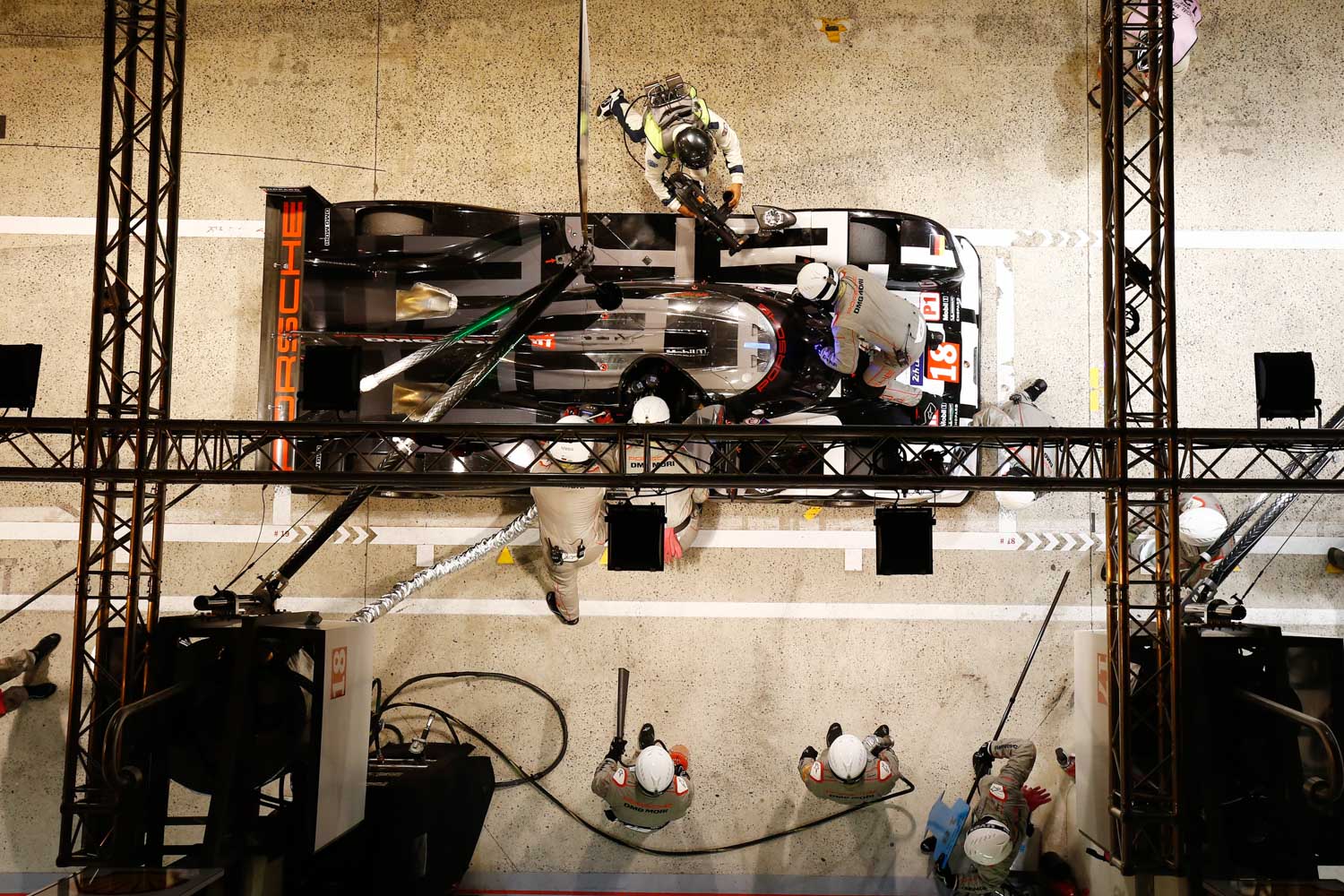

Watching during the daylight hours is fascinating as drivers and teams jockey for position, but when the sun disappears over the horizon, there’s a whole new aspect to the race. Compared to the daytime, more fans come out over the late evening and early morning to watch the racing. The cars look like Christmas trees taped to the back of rockets, with LED lights glowing brightly along most of the bodywork contours, the back-lit large race numbers on the side of the cars, the bright red glow of the brake discs, brake lights flashing on and off, and headlights bright enough to melt tarmac at 50 metres.

Engines take on a different growl as they suck in lungfuls of cold, damp air at 1.30am, and you can hear them kilometres away in the still night air. Standing in the dark, you hear the change in engine note as the cars rise and fall through the undulations in the long straights at 300kph-plus. Then, all of a sudden, the track is lit up in an almost-too-bright glare as each car appears around the bend, and rockets past where we’re standing, immediately followed by the blood-red glow of the tail-lights as the car accelerates away.

The engine notes dim at the same rate as the rear tail-lights, and the car disappears into the murky French countryside on its way to completing another lap. You just have enough time to draw breath before the next car arrives, and it happens all over again.

It’s bloody fantastic, and something that all motorsport fans should get to witness before heading off to that great racetrack in the sky. And when Kiwis win the race as well, it doesn’t get much better!