data-animation-override>

“Is VIN-ing an old car really that hard? We follow one through the system to find out”

Buying a car that isn’t road legal can be a scary prospect. What if you spend all that money only to find out the car is no good? There are plenty of uncomplied cars for sale at the moment, and if you decide to import your own, that will need to be complied too. In this article we’ll show you that the process isn’t really scary at all, and as long as you’ve got a good, safe car, getting it on the road is nothing to worry about.

Step one

The first step when planning on VIN-ing for a car, or even looking at a car that hasn’t yet been VINed, is to check the paperwork.

Since you’re reading this, chances are the car you are looking at importing will come from America, and will probably be more than 20 years old. Assuming this is the case, you will require three main documents:

1) The vehicle’s overseas registration papers (certificate of title / pink slip).

2) Evidence of vehicle ownership (purchase receipt, bill of sale).

3) Evidence that you are the importer of the vehicle (ie, import entry documentation in your name, shipping papers or bill of lading).

Copies of the documents will not suffice, they must be original. If a car doesn’t have the original documents with it, walk away.

Lastly, you will also need evidence of your New Zealand residency (driver’s licence).

If you’re confident that you have all the required paperwork, head to your local compliance centre.

To run our test car — a 1977 Mercury Marquis — through, we used North Shore Compliance Centre. The guys there process hundreds of cars a week, many of them American vehicles, which comes in handy if your vehicle fails. Once they have all the required documentation, it’s time for the inspection to begin.

Step two

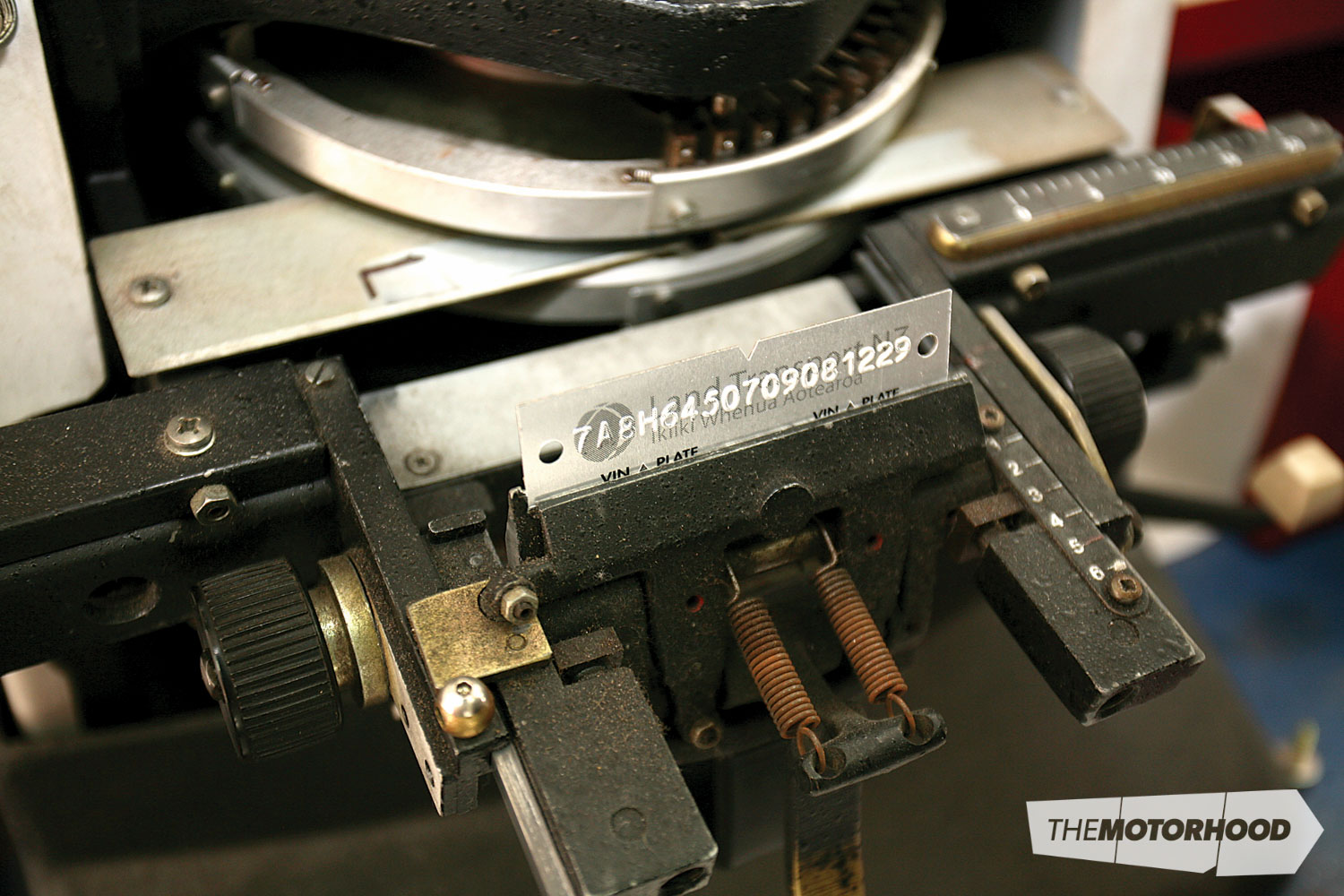

Before any inspection can take place, the vehicle must be assigned a VIN number. Technically, applying the number is VIN-ing a vehicle and the rest of the procedure is compliance, but it’s more common for the whole procedure to be referred to as VIN-ing. This number allows for the vehicle to be identified in the government’s system.

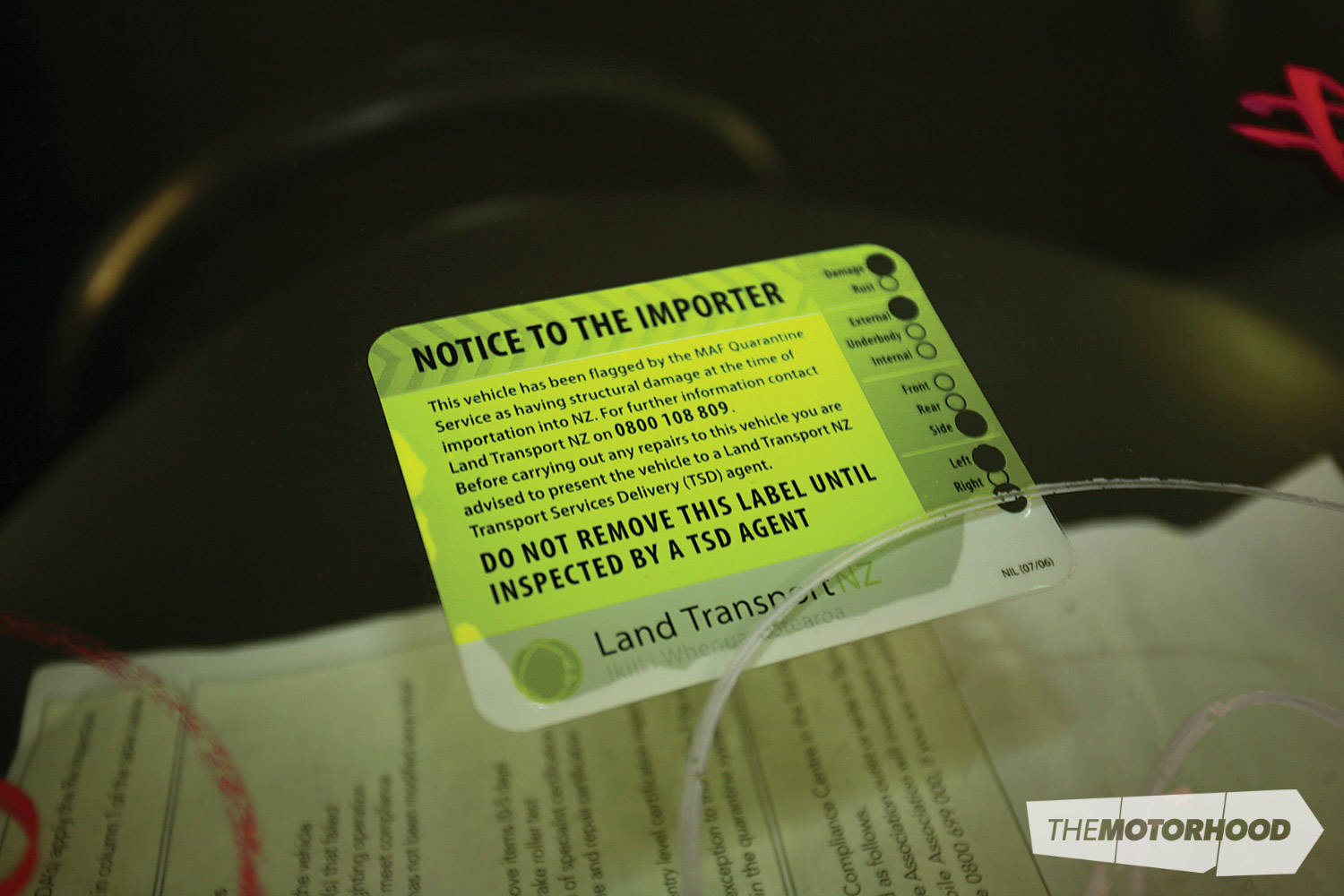

As well as the small plate that gets riveted to an immovable object in the engine bay, the number is also sandblasted into the vehicle’s rear window. At this point information about the vehicle, such as year, make and model, along with engine size are entered into the system. Prior to this, imported vehicles will have been given an identification number by MAF as the car came off the wharf. If a vehicle is deemed to be in damaged condition by MAF, it is flagged as such in the system.

The first part of the vehicle’s inspection is removing the sill plates and rear seats. This exposes the areas of the floor pan and bodywork that aren’t visible from underneath. If a damage-flagged vehicle is deemed not to be damaged, the compliance centre is able to remove that flag from the car’s records. However, if upon inspection it appears the car has been damaged but repaired, a repair certifier must be called to check that the repairs have been done correctly. It’s important to note that you cannot just take an accident-damaged flagged vehicle to a panelbeater to be fixed. The repair certifier is an independent person with authority above and beyond that of a panel shop.

With the rear seat removed, the inspector checks for any rust or damage. To proceed there must be no signs of rust within 150mm of a seatbelt anchor, or damage within 50mm. “If we suspect anything, we will often remove more of the vehicle’s interior,” says Wayne Bending, our inspector.

There are other things to consider regarding seatbelts, which require a Low Volume Certificate if they are aftermarket items. “Things do get more complicated if a vehicle has had aftermarket seatbelts, so as long as the original belts are in good condition, leave them there, unless you can find direct factory replacements,” Wayne advises.

Our ’77 Mercury test car is in great overall condition and, having come from California, there wasn’t a hint of rust on it.

Assuming the inspector is happy with the condition of the sills and under-seat area, he initials the windscreen and the vehicle is put back together.

“Now that the MAF guys do their job, we don’t find as many odd coins as we used to. Someone must have a collection somewhere. We still get to see some very odd and poorly done repair jobs, though.” Luckily for us, the Mercury passed with flying colours, and we even managed to find a quarter dollar!

Step three

Inspection time.The vehicle is put onto a hoist, at first lifted until the wheels are approximately 100mm off the ground. While in this position, a special tool not entirely dissimilar to a crowbar is used to apply pressure to the wheels to check for movement in suspension and steering components. Our low-kilometre Mercury again passed with no problems.

From here the hoist is raised until the centre of the wheels is around eye level. All four tyres are inspected for unusual wear patterns and any signs of rubbing. Aftermarket wheels don’t cause our inspector any concern, as long as they don’t rub on anything and as long as no wheel spacers are used. By the new look of the tyres on the Mercury, I would guess they have been fitted here before the vehicle was sent to be complied, and so they pass easily. Tread depths are also noted at this point, since the end result of the inspection, as well as compliance, is giving the vehicle a Warrant of Fitness.

Next, the hoist is raised to allow the inspector full access to the underside of the vehicle. Starting from the rear, Wayne looks for any signs of rust and/or damage, as well as the condition of items such as shocks, brake hoses, driveshaft universals, seatbelt anchorages, engine mounts, and steering/suspension bushes. “We know they are not new cars and we take that into consideration. However, they must be safe,” says Wayne.

Our Mercury had obviously been well looked after and maintained, and we were able to go straight through to the next step, checking the brakes, without any hold-ups or repairs required. With all four wheels removed, the front discs and pads were checked for thickness, as were the rear drums. “Wheel cylinders leaking are a common occurrence,” Wayne explains. “People tell us they have checked them but they don’t check under the rubber seals, and that’s where they leak.

“Another hassle we have is people not leaving their lock nut keys in the car. We have to either get them to bring it in or the car will fail, as we can’t check the brakes [without them].”

With the wheels off, things like body mounts can be checked, as can steering joints and coil springs. Again, our Mercury flies through.

Step four

Now that we know everything looks as if it will work, we put it to the test. “Inhibitor switches are a very common failure,” Wayne notes, which means that if your car is an automatic and you can start the engine while it’s in gear, it’s not going to pass.

Once that hurdle is passed it’s the lights, head/tail and indicators, along with the horn, which nearly makes our cameraman drop one very expensive camera.

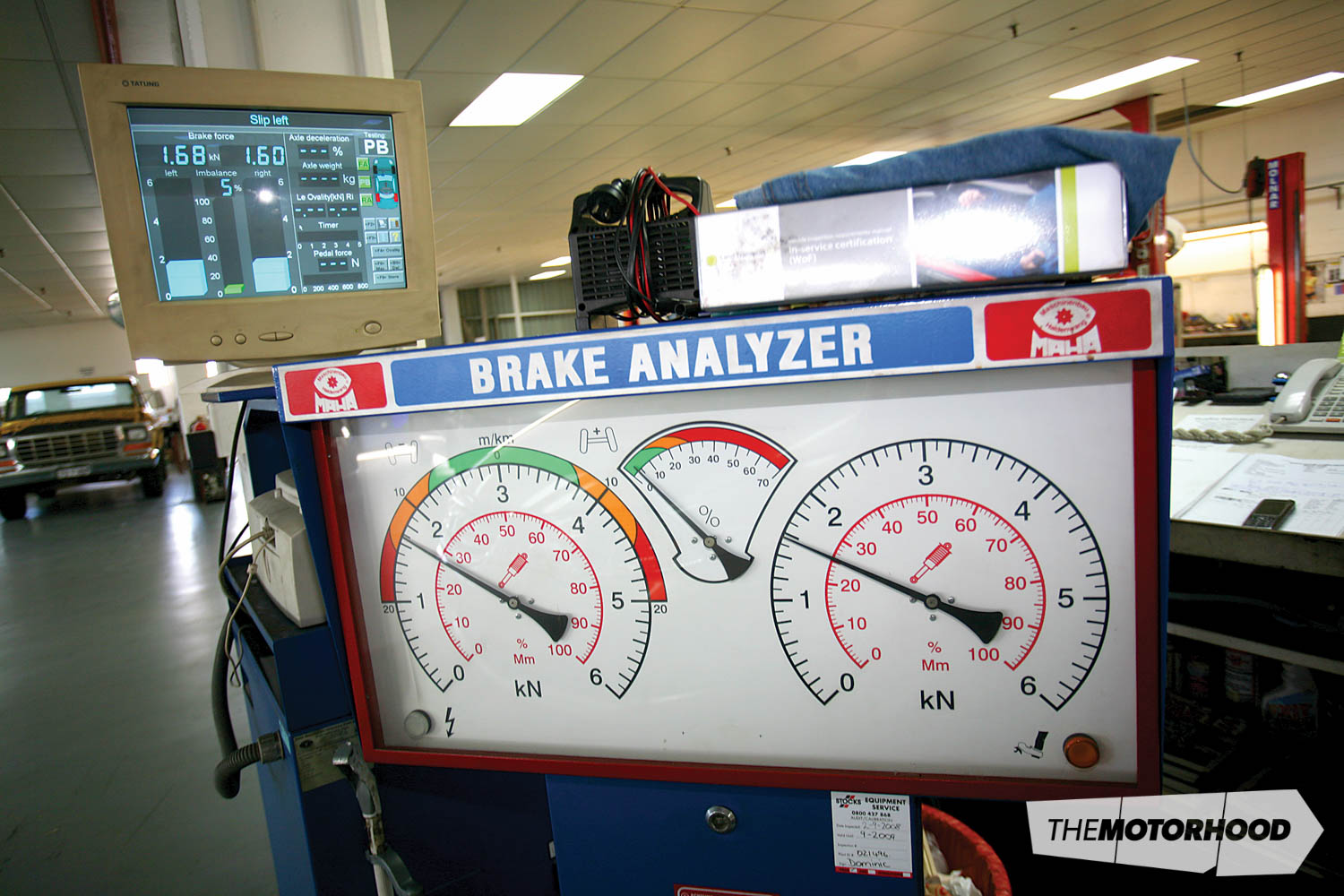

The car is then driven up onto the brake-testing machine, as first the front wheels, then the rear wheels, then the handbrake are all tested. The tests are all too easy for the Mercury, which again flies through.

The common failures in these tests are people not changing the headlights from right facing to left facing, or people purchasing cheap lights they think are left facing but turn out not to be. These must be changed before a car can be complied. If the car you purchase is right-hand drive, you shouldn’t have a problem, since it will probably have come from a country that drives on the left-hand side of the road. The focus of the headlights is also checked, as it would be for a Warrant of Fitness.

That’s the end of the testing procedure, surprisingly easy with the Mercury, as it would be with any decent car. Paul Urqhart, manager of North Shore Compliance Centre, says, “On average it costs people around $2000 to comply an American car. While it’s only $395 plus GST with us, there’s often around $1500 in repairs and changes to be made.”

Step five

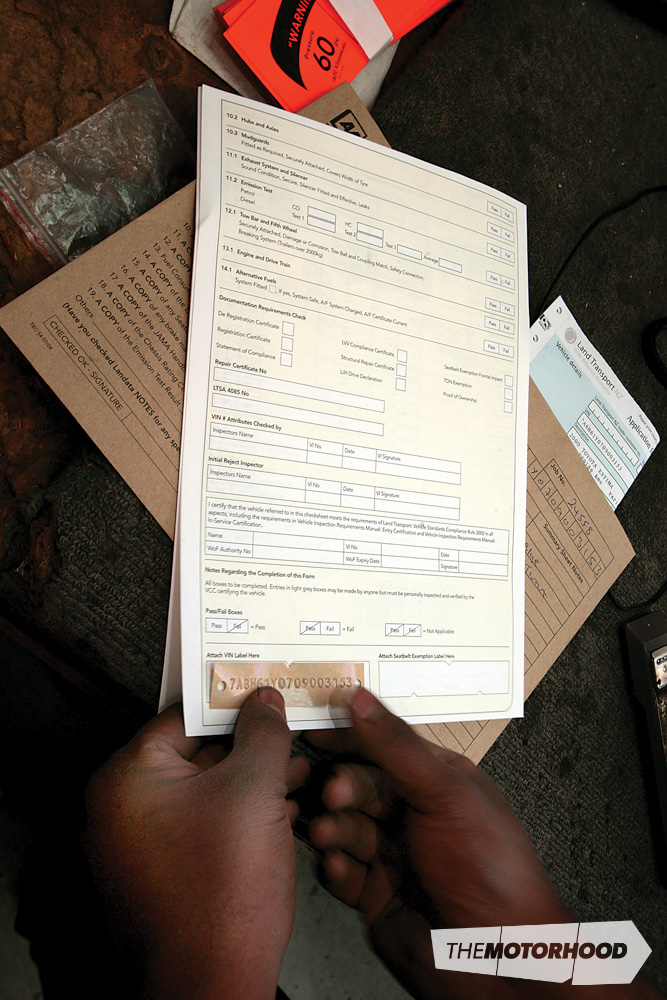

The final step is completing the necessary paperwork, an MR2A form along with a left-hand-drive declaration. The declaration states that the vehicle cannot be sold for a period of six months. This is what can put people off buying a non-VIN-ed vehicle that is already imported into New Zealand, as the vehicle must be registered in the importer’s name.

Our Mercury was imported by its current owner, which made things simple, and once he’d signed the paperwork the car received its six-month Warrant of Fitness. All that was required for the owner to hit the road was registration to be paid for and put on the window.

Other things to consider

If the vehicle you imported or purchased has been modified in any way it will require a Low Volume Certificate (Cert) plate. Paul’s advice is to bring the vehicle into the compliance centre first. This will see the car receive a VIN number. The inspection will take place as per usual, however the car will fail on needing a cert. Most compliance centres deal with certifiers all the time, so they will be able to arrange one to come and check out the vehicle.

The downside of the whole process is that if your vehicle fails its VIN on requiring a cert or anything else, you have just 21 working days to make changes and get it rechecked. If you do not make the required repairs within this timeframe, the inspection will be required again, resulting in more cost to the vehicle owner.

The reason behind this is safety. “It’s basically to ensure the vehicle doesn’t travel too far, and the condition of it change,” Paul says. “Often with old cars, it’s hard to get parts here and fitted within that time period. The only way around the 21-day rule is if the vehicle doesn’t leave the compliance centre in that time,” — meaning the compliance centre must be the one that fits the parts.

Although it may sound as if Paul is trying to make money by offering to undertake repairs, having the compliance centre undertake the work is often the smart way to do it. “We’ve been repairing old cars for many years and we know what bits off one car will fit on another, and where to get them from for the right price. And, of course, how to fit them properly,” he says. Not every compliance centre offers this service, but taking into account the above statement, it certainly makes sense to choose one that does.

Summary

The process wasn’t difficult at all. It’s really just like a slightly more in-depth Warrant of Fitness check-up. This is, of course, assuming the vehicle is more than 20 years of age. If not, it will be required to meet emissions and frontal impact standards, and will undergo a more comprehensive strip-out of interior parts.

If you’re looking at buying an un-VIN-ed car, I wouldn’t shy away from it — unless you aren’t sure about the quality of the vehicle or it doesn’t have the required paperwork.

The other thing to consider is that you will be registering the vehicle in the importer’s name, so make sure it’s them you are buying it off, or you at least talk to them first and trust them. When it comes to getting a VIN, you will have to get them to the compliance centre to sign documentation and provide identification, and the same again when you get the vehicle’s registration. If you don’t trust that you will be able to get the importer to the compliance centre, then you may well end up in a sticky situation. However, most guys who import these vehicles are well aware of what is involved, and as yet I can’t say I have heard of any deals going sour between the two parties.

Photos: Dan Wakelin

This article was originally published in a previous issue of NZV8. Pick up a copy of the edition here: