data-animation-override>

“Gerard Richards travels back in time to Auckland in the ’60s and recalls the career of Peter Lodge — the man who built a hot rod that was, at the time, lauded as the fastest in the country”

Children of the ’60s, such as myself, grew up on a diet of ‘Boy’s Own’ adventures. The stuff you’d read in Tiger and Lion comic annuals, the many war comics of the day, even Famous Five books — if you get my drift. They were simpler times, not necessarily better, but most things seemed more certain than they do in the present day.

Part of that era for me was that Auckland’s North Shore in the mid ’60s was an undeveloped paradise of gravel roads, pine forests, paddocks, and bush — a mecca for day-long adventures with your mates out in the wilderness. Back then, there were zero concerns about releasing children into the countryside to learn about the great outdoors. With the rash of constraints foisted upon us by the contemporary nanny state, about the closest present-day kids get to those experiences these days is online and virtual — but that’s another story.

We’re talking the ’60s here — and one of the pillars of that era’s formula for supposedly developing a boy’s character was that great bastion of the British Empire — the Boy Scout movement. Created by a noble chap, Lord Baden Powell, in the aftermath of the First World War, the main premise of the movement was the idea of enhancing ‘real’ masculine traits. It was thought that the emancipated urban culture that had mushroomed in the years directly following the Great War was gradually eroding the qualities of young manhood. No fear, Baden Powell was there to stop the rot!

Forgetting the military uniform and discipline thing here for a moment — some of which could be deemed debatable — being a Boy Scout offered one big plus: adventure with your mates. I took to it like a parched man discovering a pub in the desert.

Grass-track fun at Worrall’s Farm, Kumeu, Auckland. This was the scene of Peter’s early racing escapades. No. 14 car seen here is Brian Walsh’s ‘Nuttin Special’ sports car, powered by a 1000cc JAP engine. No. 22 is Chris Moon’s ’32 flathead-powered sedan (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

Leader of the Scouts

Everything suddenly got even better in the winter of 1970 with the arrival of a young and enthusiastic new scout leader — and he turned out to be a hard-core thrill seeker himself. He was none other than famed hot rodder Peter Lodge. Born in 1947 he was only about eight years older than us 14-to-15-year-old raw recruits.

Peter immediately stamped his presence on our group, particularly on those of us who had an addiction for fast cars and motorsport. We obviously knew who he was, so he achieved cult status instantly. Even within our naive adolescent one-track minds (possibly that should be two-track minds; focused on hot-car dreams and hot-young-girl dreams) we sensed there was more about him than immediately met the eye.

Unlike a number of more usual scout leaders, those with ex-military wartime backgrounds, Peter was more a product of the ’60s self-expression generation. But he fervently believed in the ethos of us being challenged in all manner of circumstances, and that the scout movement was there to develop our self-reliance as young men. The legend and traditions exemplified by British writer, Rudyard Kipling, in The Jungle Book were equally important to him.

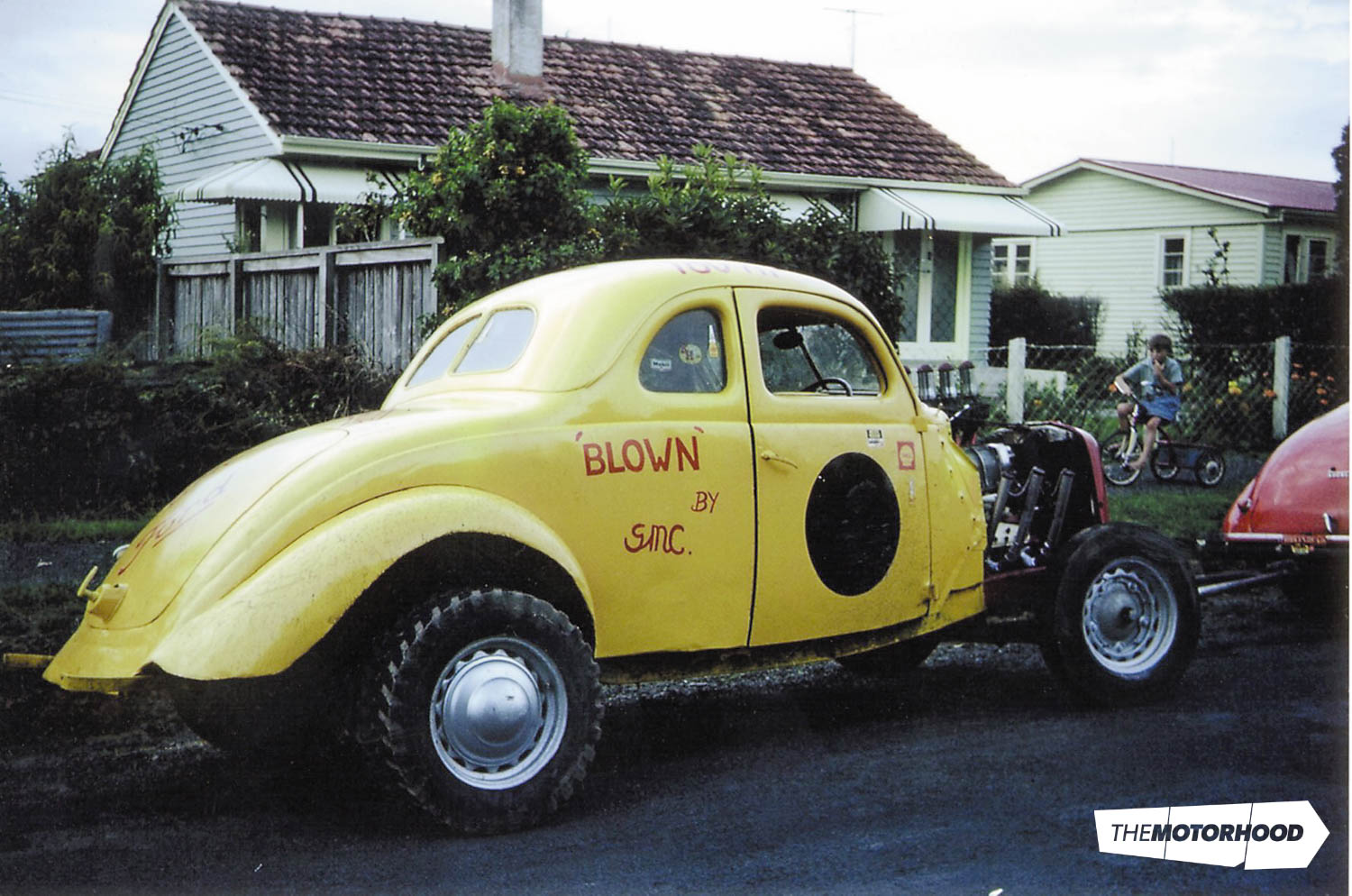

Indeed, ‘Baloo’ (the wild bear who appeared in Kipling’s The Jungle Book) was the chosen name that was painted on the side doors of Peter’s already legendary blown and injected Chrysler Hemi-powered Fiat Topolino–bodied, Fuel/Altered drag car.

Swamplands at Mercer, south of Auckland. This is the first organized and official drag racing meeting at Kopuku in 1966. Peter’s blown ’37 coupe is in the centre of the picture (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

Early years

How did a young man just past 20 in the import-strangulated backwater of New Zealand acquire, during the summer of 1967–’68, the most ballistically powerful racing engine known to man? At the time, that must’ve been almost tantamount to walking on water!

Understanding the innovative nature of the engineering, fitting and machine-turning trades that Pete and his mates grew up in during the ’50s and ’60s, goes a long way to providing the answer. Like many of fellow automotive gear heads of that era, getting new ‘hot parts’ wasn’t a happening thing and, as a result, skills were quickly applied to adapting and making parts early on, a vital element when it came to developing, modifying and fixing cars.

From the fertile fields of Rangitoto College in the late ’50s to early ’60s, Peter forged some strong bonds with fellow car nuts such as Alan Smail and Brent Purdy, amongst many others. These young men were to form the nucleus of the legendary building and development team behind the iconic ‘Baloo’ drag car. They would become life-long friends, their early camaraderie nurtured through shared adventures such as building a log cabin retreat in a bush-clad backwater — and that would also include many wild weekend escapades, all accommodated by a friendly landowner (this was the legendary Clemow’s Orchard in Rosedale Road, Albany — today, a housing subdivision wasteland). Early school-morning visits with his mates to fix and check possum trapping lines at Clemow’s combined to develop a sense of self-belief and a can-do attitude for both Peter and his friends.

With their departure from school (the same school the writer would later attend) around 1962, Peter’s ‘gang’ funnelled their adventurous spirits into a passion for working on, modifying and improving their cars. In 1965, when he was 18, Peter bought his father’s ’49 Ford V8 Single Spinner, initially in a 50-per-cent share along with a mate. An earlier (while still in his father’s ownership) double spin-out, while testing the Ford’s road-holding capabilities on the Rosedale Road gravel, had seen the car’s rear end smash through a fence. All that afternoon was spent straightening the bumper to avoid possible detection of the incident. Not long into his ownership, Peter bought his fellow cohort’s share and became the youthful owner of a very groovy first set of wheels.

By now, Peter was a fitter and turner apprentice at the Chelsea Sugar Works, after doing a stint as a builder’s labourer for his father — who was a well known builder around the Bays. This association with the Sugar Works would stand him in good stead over the next few years — as he could use the company’s equipment to make or modify various auto parts.

Kicking up the dust at Worrall’s Farm. Unknown sedan (a ’34 V8) leads what could be Rob Campbell’s white ’37 coupe, with Alan Smail’s A40 ute taking the outside line; Kumeu 1966 (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

Motoring memories

I have particularly fond memories of the ‘Tank’ — Peter’s ’49 Ford V8 — as no doubt he has as well. Painted in ‘beaver brown’ (as described by Peter) with a white roof, it was a pretty slick piece of steel that kind of cast into the shadows the array of Ford Anglias, Hillman Hunters, Vauxhall Victors and humdrum Holdens that most of our fathers drove at the time. We made a few trips in the Tank, including one to an Otorohanga deer farm in 1971 that remains etched in my mind. That car had presence and an awesome old-car aroma. It was Peter’s daily driver and, in due course, would also act as the tow car for Baloo — but the Ford also did some early duty as a grass-track racer.

While recalling legendary cars of my youth, I should mention one other iconic scout leader who also had an impressive set of wheels in the shape of a 1956 De Soto V8 — a car owned by Ray Allen, a bit of an eccentric character. He was regularly spotted at auto accidents all over the Shore with a camera — to most, that seemed a bit macabre. I learned only recently from Peter, that Allen had a short-wave radio and monitored the police frequencies — that was how he acquired the trick of being Johnny-on-the-spot at local road accidents. Apparently, he was supplying photographs to the local press. He also wore wigs and would rock up anywhere kitted out in military uniform, so you could say he was a bit unusual. But all that, of course, was forgiven if you had a front seat pew in his De Soto — with its cool dash and rumbling V8 — heading out of the scout den car park on some mystery adventure.

Back to Peter’s ’49 Ford, a car that still holds fond memories for him, as he was at the wheel of the Ford on the momentous occasion in 1965 that he met Janice, the girl who would become his lifelong partner. That particular meeting was a classic piece of typical, ’60s, boy-meets-girl folklore. Parked outside the local chippie in Mairangi Bay, Peter and the boys were ensconced in his Detroit V8 iron, waiting for their order. Just then, two young women got off a bus and, as rain conveniently started to fall, after some initial hesitation they approached the car. The hand of fate played its ace, as Janice’s friend recognized Alan Smail, one of the guys in the front seat, and asked if they could get a ride up the hill. The rest, as they say, is history.

Today, Janice and Peter have been together for 48 years and she remains his most ardent fan. They met when she was 14 and he 18, and the party that night that kicked things into gear has been going ever since.

Weekends saw the couple hanging out with the rest of the petrolhead gang, cruising the trendy North Shore beach rendezvous in their old V8s and Zephyrs. Mind you, some of the tribe had machinery with serious street cred — one of Peter’s mates, Phil Prince, drove a ’39 Ford coupé equipped with an ex–Johnny Riley stock-car racing Chrysler Firepower mill under the hood! Janice’s sister, Nancy, hooked up with Alan Smail and they were all part of the growing, local hot rod scene that was about to become the nucleus for the North Shore Hot Rod Club. For this crowd, stopping for cool lime and creaming soda milkshakes, served in aluminium cups, was always a highlight when they parked up to check out the ’60s beach scene and kick some tyres.

However, Peter and the ‘boys’ had ambitions beyond cruising in their cars, even if their bank balances couldn’t quite support a headlong plunge into racing. The latest copies of Hot Rod, the cult American magazine, were filtering into New Zealand and opened up a whole new vista of possibilities. The gang drooled over details of the burgeoning US drag racing scene, especially the wild new class of Altereds and Gassers — the ultimate challenge in their eyes. Massive power in a radically modified, short-wheelbase, pre-war coupé just had to be top in the excitement stakes.

Alas, drag racing simply didn’t exist on the local hot rod front in 1965 — at least in any organised format. To use Peter’s words, “drag racing was in its infancy in Aotearoa”, and car clubs (there weren’t many hot rod clubs then) usually ran sprints, hill climbs, gymkhanas, and grass-track racing, all of which the lads were into with a grin.

While this stuff was good fun, the fitter and turner Campbell’s Bay Hot Rod Rebels had aspirations towards the supreme asphalt showdown — drag racing. Then, rumours of a semi-permanent location for quarter-mile racing gathered substance during the winter of 1965. With the dream looking as if it would become reality, Peter tracked down a new beast to build up so he could take an active part in this ground-breaking development.

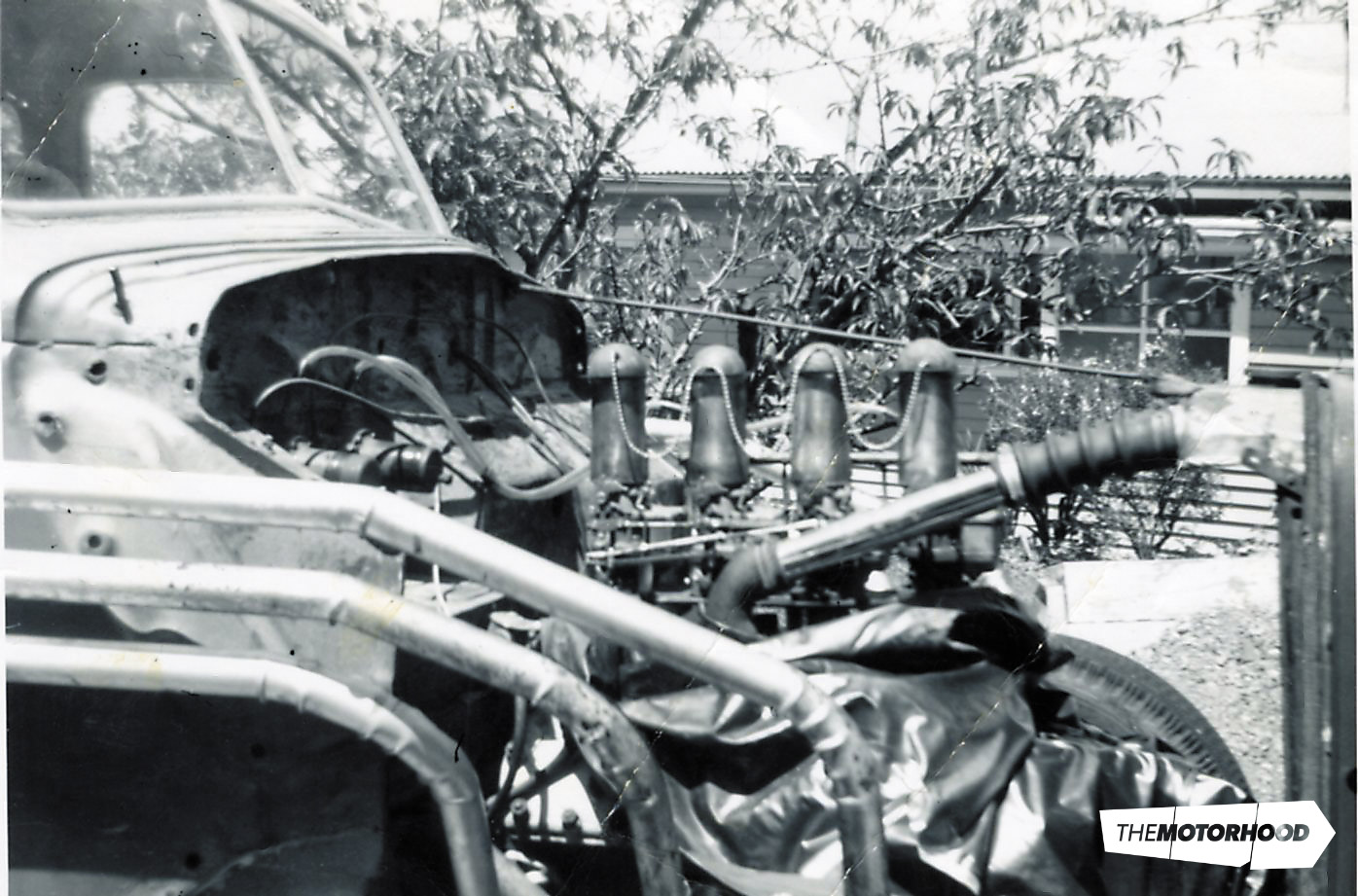

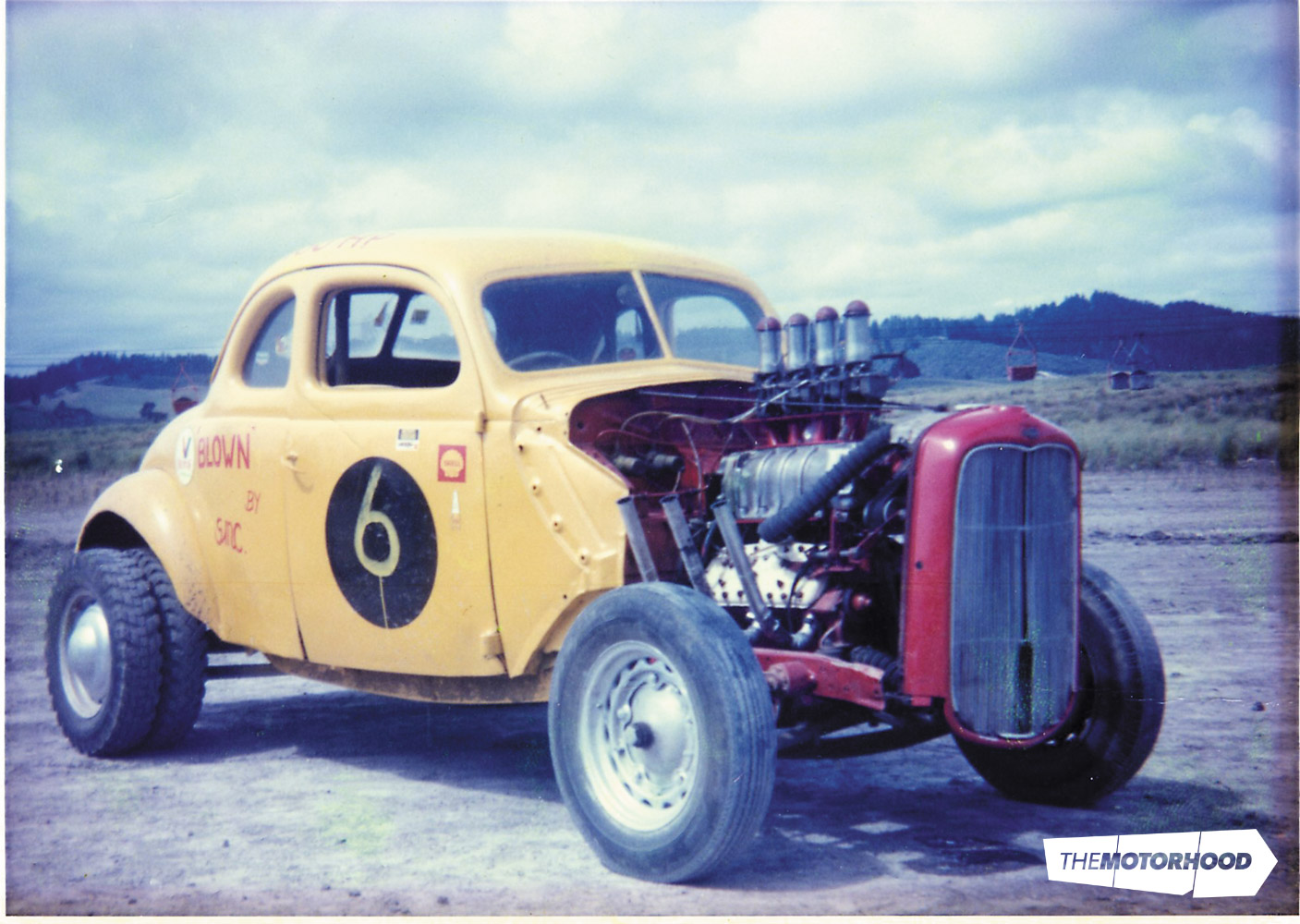

Peter’s amazing ’37 Ford, powered by a supercharged Mercury flathead, seen here parked outside the Lodge family house in Kowhai Road, Campbells Bay, on Auckland’s North Shore (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

Thunder road to folk hero

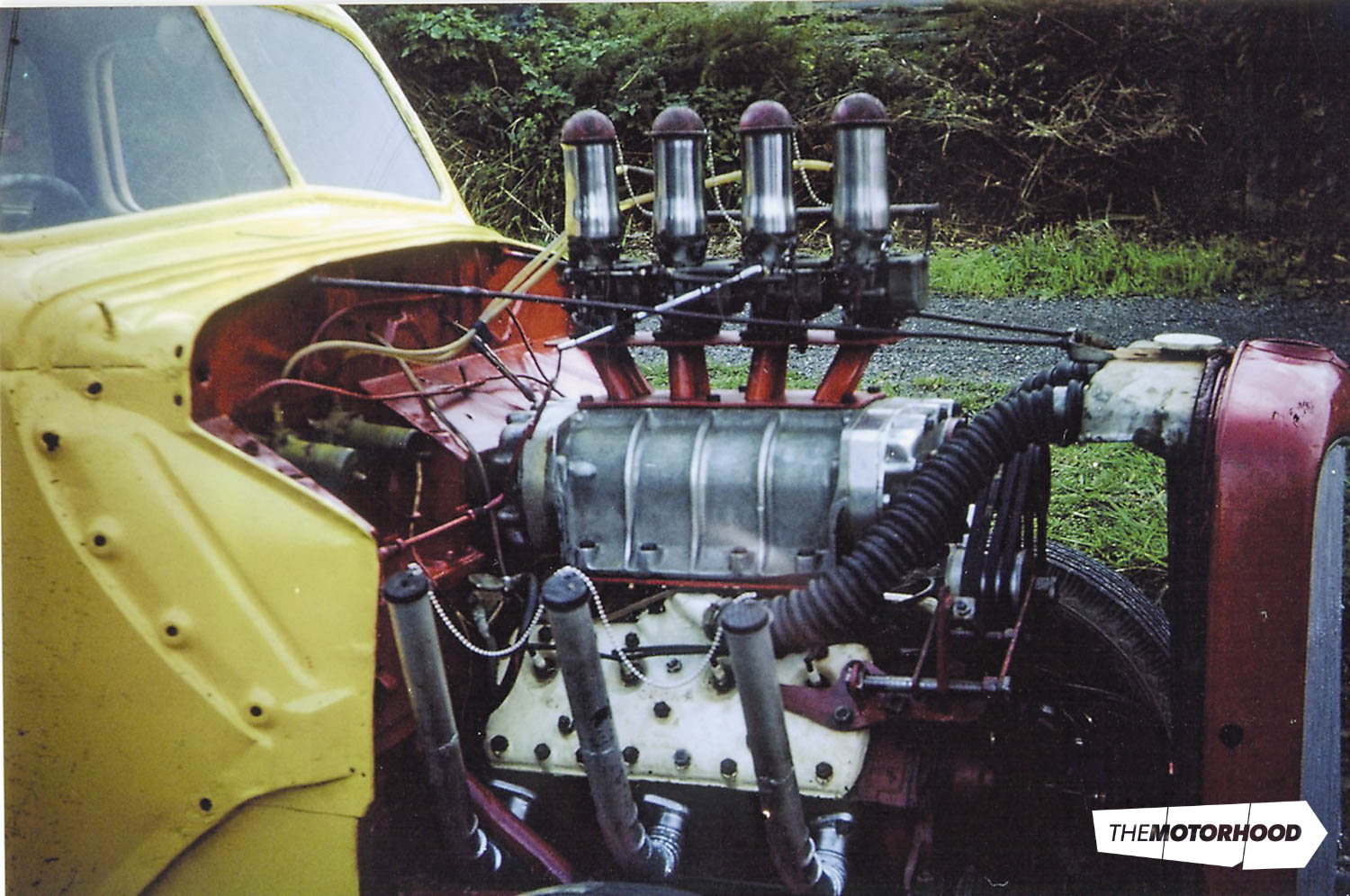

He bought a ’37 Ford coupé in fairly rough condition and tidied it up. A good Mercury flathead V8 was acquired, and then it got really interesting. Though there was nothing extraordinary with this car/engine combination around that time, it was what Peter and his mates did next that made the difference. Their masterstroke was (through skilled engineering) to graft four Strombergs and a 6-71 supercharger onto an adapted manifold that Peter welded up at the Chelsea Sugar Works. The resulting car could certainly be regarded as being a rather advanced piece of exotic speed equipment, especially in New Zealand during the ’60s.

Looking back on those days, Peter said, “I’d heard that a friend, Johnnie Tombs, had a ‘blower’ — so I fronted up with ‘can I borrow it for a while?’ It was a bit of a blast when we got that going. That Mercury flathead was a good mill, too.” The car would also be the seed that, within a few short months, would set the team off on the ultimate quest for unrestrained mind-blowing power.

Right then, though, armed with the supercharged ’37 coupé they had a frontline charger ready to make its debut at the inaugural meeting, held at the Kopuku Dragstrip, near the South Auckland town of Maramarua. New Zealand’s first semi-permanent drag strip was located adjacent to an open-cast coal mining area (supplying coal to the old Meremere power station), using a strip and access roads that were unpaved. The light grit surface obviously wasn’t that wonderful for traction, and there wasn’t a slick tyre in sight, so things were fairly rudimentary, to put it kindly.

The new strip was lined with 40-gallon drums, and the word had gone out to the faithful that ‘The Drags’ was the place to be. As a result, the hot rod fraternity was out in force for that first meeting, many of them racing their street cars. The competitors ran a diverse and sometimes rough-looking array of hot Zephyrs, street rods and grass-track racers with the occasional early, purpose-built drag racing machine — such as the Sanders-Lucas rail or Bob Rossiter’s dragster — dropped into the mix.

A serious piece of kit — Peter’s ’37 coupe with GMC blower and dual tyres on the rear. Pictured here at Kopuku where he set the fastest time at the first official New Zealand drag racing meet, 1966 (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

However, at that inaugural meeting in 1966, Peter and his mates’ 1937 coupé was sort of the class act of the field on day one, especially with all that state-of the-art hardware perched on top of the Ford’s V8 mill. Indeed, Peter had the supreme distinction of running the fastest time of the meeting, at 17.14 seconds. Although there had been odd quarter-mile drag racing sprint before, this was the officially recognised beginning of organised drag racing in New Zealand. Peter’s success on the day, in hindsight, was a great honour — effectively, Peter recorded the fastest pass at the outset of a new era.

Unfortunately, later in the day the Mercury flathead was damaged, so the team couldn’t run for Top Eliminator.

The Campbell’s Bay Hot Rod Rebels only ran the supercharged coupé at Kopuku once, though they fronted regularly at the famed Stevenson scoria quarries in East Tamaki (in Auckland, near Mt Wellington), a celebrated early powerhouse of the local hot rod racing scene. They also competed regularly on the North Shore circuit, running frequently at places like Worralls Farm, hill climbing at Kumeu and taking part in sprints at a small dirt track circuit in Silverdale with both the ’37 coupé and Peter’s old ’49 Ford.

The wild excitement of drag racing and hot rods was taking formative steps in the Auckland area and Pete and his mates were in on the ground floor. They were exhilarating times, with new machinery starting to emerge locally. In the finest Kiwi No. 8 wire tradition, this first wave of quarter-mile beasts were all backyard specials.

There was no speed equipment to speak of, and ingenuity was the order of the day, matching and adapting equipment from wrecks or wherever suitable bits could be found.

By 1967, even in this pioneer phase, Peter had seen the future and been seriously seduced by the sort of exotic projectiles he was reading about in the US Hot Rod magazine. He and the team wanted in on this action.

Kerrs Road, Wiri, South Auckland; Owen Campbell has the jump in his GMC six–powered T-bucket (‘Junior Jimmy’) over Dave McDougall’s 292ci Ford V8–powered Austin (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

Warp-factor horsepower

Racing the ’37 coupé had whetted Peter and the lad’s appetites for more radical drag race action, and they were looking at the wildly modified ’30s-style pre-war-bodied Altered class. The flathead V8’s days of being the hot rodder’s weapon of choice were passing into the annals of history, those types of engines being superseded by the high compression Chevy V8 and that ultimate tarmac burner: Chrysler’s mighty Hemi V8.

Operating out of Auckland’s North Shore (pretty much a sleepy hamlet back in the mid ’60s), these sort of serious aspirations for drag racing glory might have suggested the boys were indulging in some of the delusion-enhancing chemicals made popular by hippies of the day.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. These guys knew exactly what they wanted to create — although just how they were going to go about achieving this wasn’t entirely clear as they embarked on their ambitious project.

If you wanted to go really fast down the quarter then, like now, you needed a big-block Chrysler Hemi with all the trick gear. Peter wanted badly to get his backside into a rig running this sort of equipment. As chance would have it, one of Peter’s flatmates at the time came from Wanganui, a town that boasted one of the few speed shops in the country, with tenuous links to acquiring V8 engines from North America. Together, they called Freeman’s Motor Supplies in Wanganui, hoping to use local knowledge to crack the code and enter into the import speed equipment grapevine.

There wasn’t a brand-new Hemi 392 just waiting on the shelf for them to pluck, of course. So they placed an optimistic order for that state-of-the-art drag racer’s jewel — a 1957 300C Chrysler Hemi 392 V8 — and figured that would be the last they’d hear about it as the order would, no doubt, hit the blockade that was the government import licensing dragnet of the times.

Three months later, a stunned Peter received a call to come down and pick up his engine.

Looking back, Peter reckons they landed the demon mill in late 1967, when Kopuku was going strong. Back then it was the pinnacle; the 392 was the perfect engine, with its two four-barrels, solid lifter cam and adjustable rockers. In Peter’s words: “As good as it came off the line, 700lbs of pure grunt.”

The 426 had just emerged at this stage, but the aftermarket speed equipment for it hadn’t been fully developed, or wasn’t easily available at that time. The team now had an engine, minus some major components and no car, as the ’37 had been sold. Briefly, a ’33 three-window Ford coupé was considered as the intended recipient of the widow-making engine, but it was pretty rough and needed a massive amount done to it. Roy Mann contributed some work on the car but when the mighty mill was looking like a no show, Pete moved the coupé on. With that out of the equation, they decided to start from scratch and build up a purpose-built drag racer with their own frame and everything. Talk about aiming for the summit of Everest on your first climbing attempt!

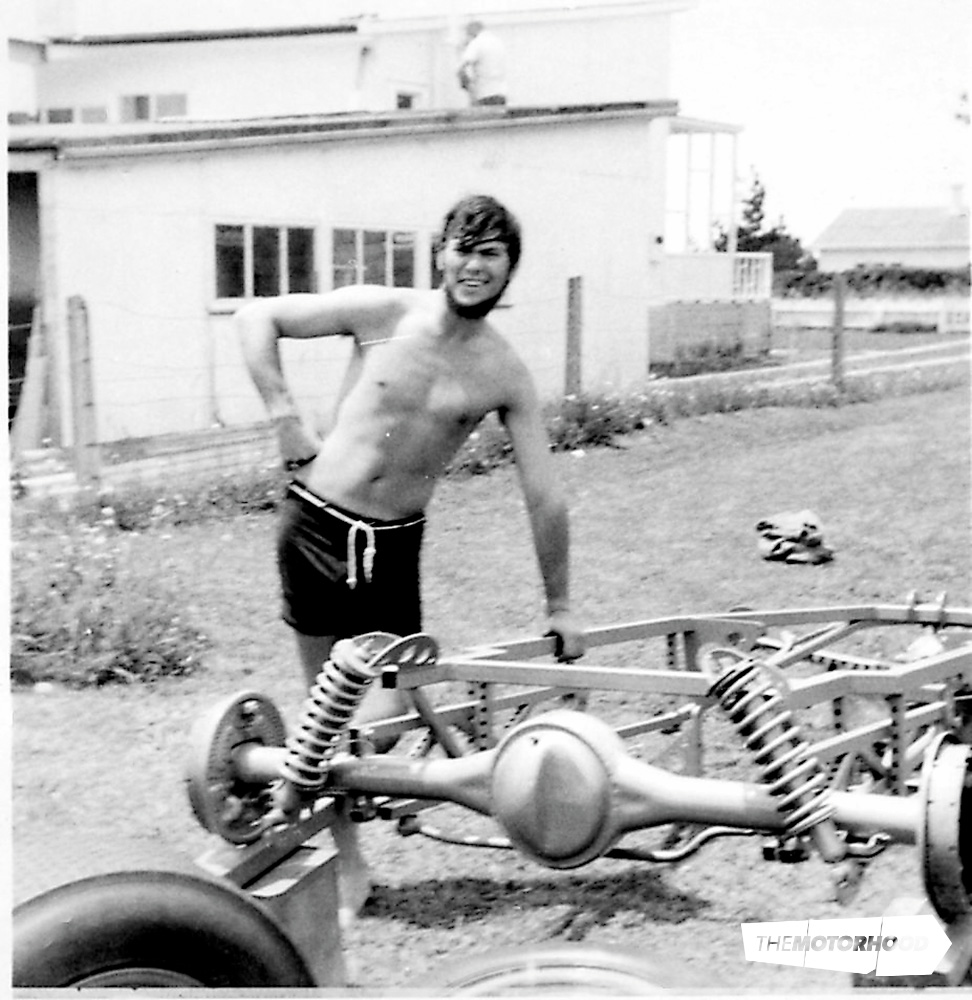

Looking ahead to part two of our story — this photo taken in early 1968 sees a proud Peter posing in his backyard beside the completed chassis of what will become Baloo (Photo: Peter Lodge collection)

By this time Janice’s dad — Arnold ‘Arn’ Reed — had also become closely involved with the project. Arn was an ex-American GI who fought at Guadalcanal, amongst other places, survived and returned to New Zealand to wed his Kiwi sweetheart.

His input became a critical factor as much as the others during the car’s early development, and he would continue to assist throughout Peter’s subsequent drag racing campaign — and that involvement would extend right out to Peter’s much later ‘Hombre’ years.

With a skilled technical background, like so many ex-servicemen and hot rodders, Arn also had vital contacts in the US and was able to help when it came to sourcing essential parts. Not the least, he was also able to provide a shed at the back of his Torbay property where the fledgling team was able to build the car.

Sitting in the sun on a warm spring day 2012, outside his bush-surrounded retreat with to-die-for sea views, Peter reflected on events that had taken place almost 45 years ago. Even now, he remains adamant that it was the passion and self-belief of the team that allowed them to believe that, together, they could turn their dream into reality. They just didn’t realise it at the time, and it would take a while to iron out all the weak links and those areas where what passed for knowledge was little more than guesswork.

Watch this space for part two of our story on Peter Lodge and Baloo, covering how New Zealand’s most iconic drag vehicle was built.

This article was originally published in a previous issue of New Zealand Classic Car, which you can purchase a print copy or a digital copy of below: