data-animation-override>

“The Skoda Octavia–based Trekka was New Zealand’s answer to the Land Rover — and this fully restored example has to be the best of the survivors”

When Tony Katterns was a kid, he remembers listening to adults talking about local car manufacturing and his grandfather saying, “Oh! The only thing New Zealand ever made was the Trekka, and it was a total flop!” Tony had absolutely no idea what a Trekka was at that stage, thinking it was probably some weird, snow-going vehicle used by the late Sir Edmund Hillary to traverse the Antarctic regions. His grandfather was quite a placid person, but Tony clearly remembers the conviction of his statement — it was enough to cement the Trekka name firmly in his mind forever.

Our Trekka tale might have ended then, but during the late ’90s Tony was an automotive restoration student, and he and a friend — Don Wakenshaw, nicknamed ‘Austin Don’ — decided to take a day trip down to Horopito for a look around the acres of dismantled vehicles and parts. Tony stumbled across a peculiar Land Rover–looking vehicle with a Kiwi on the badge and said, “What the hell is this thing, Don?”

“Oh — that’s a Trekka,” came the reply.

Because Tony considers himself one for the underdog, he couldn’t help thinking the forgotten little Trekka was worth restoring, and that it would be nice to save a couple of these things one day.

So, that’s where Tony saw his first Trekka — number 20 to come off the assembly line — and, believe it or not, that example is still slowly rotting away at Horopito.

Tracking down a Trekka

Fast forward 15 years, and Tony decided to take the opportunity to restore a classic commercial, a vehicle he intended to use as a runabout for his restoration business. Due to the constant workload restoring customers’ cars, time would be in short supply, so the chosen project needed to be small, simple and readily available. So, he thought, why not a Trekka?

As a professional restorer, Tony knows the best way to save money and get a good result is to start with a good car, and with that in mind, he began to delve into the Trekka network. His first port of call was Todd Niall, author of the book Trekka Dynasty. Todd was helpful with several contacts in Auckland who had Trekkas but, alas, none were available for sale.

At about that time Tony bumped into his old friend Don Wakenshaw, and asked if he knew of any other Trekkas around. “Yeah sure, I’ve got five of them!” said Don, who at that time was living in Morven and had collected about 100 Austins (hence his nickname). Tony wasted no time, paid for a couple of plane tickets to Christchurch, and the first South Island Trekka hunt was organized. After compiling a list of contacts and planning a bit of a road trip with Don as ‘Indian’ guide, they went calling on collectors they knew owned Trekkas in various states of disrepair.

“We stopped in Ashburton to visit an old-time car restorer. I got talking to his neighbour over the farm fence about Trekkas, and he invited me over to have a look at the four examples he had parked up in his farm sheds. He then sent us over the road to have a look at another sitting in a paddock. They weren’t hard to find, if you knew where to look!”

Finally, Tony found our featured Trekka near Dunedin amongst Larry Timpany’s small collection of classic cars. At one time Larry had worked for a Skoda dealer, rallying one of its cars during the ’70s. He’d bought his Trekka through a farm auction.

Tony was interested in buying this particular Trekka because it was running, totally complete and unmolested, with a live registration, and was the only restorable flatdeck version he’d seen. Subsequently, the Trekka was purchased and sent by rail to Auckland.

On a later trip to the South Island Tony purchased a couple more very good finds, choosing a sensible route by taking the time to look for ‘good ones’, as most of the Trekkas discovered were languishing in open areas, left to the elements and rusting away.

The start of the Trek

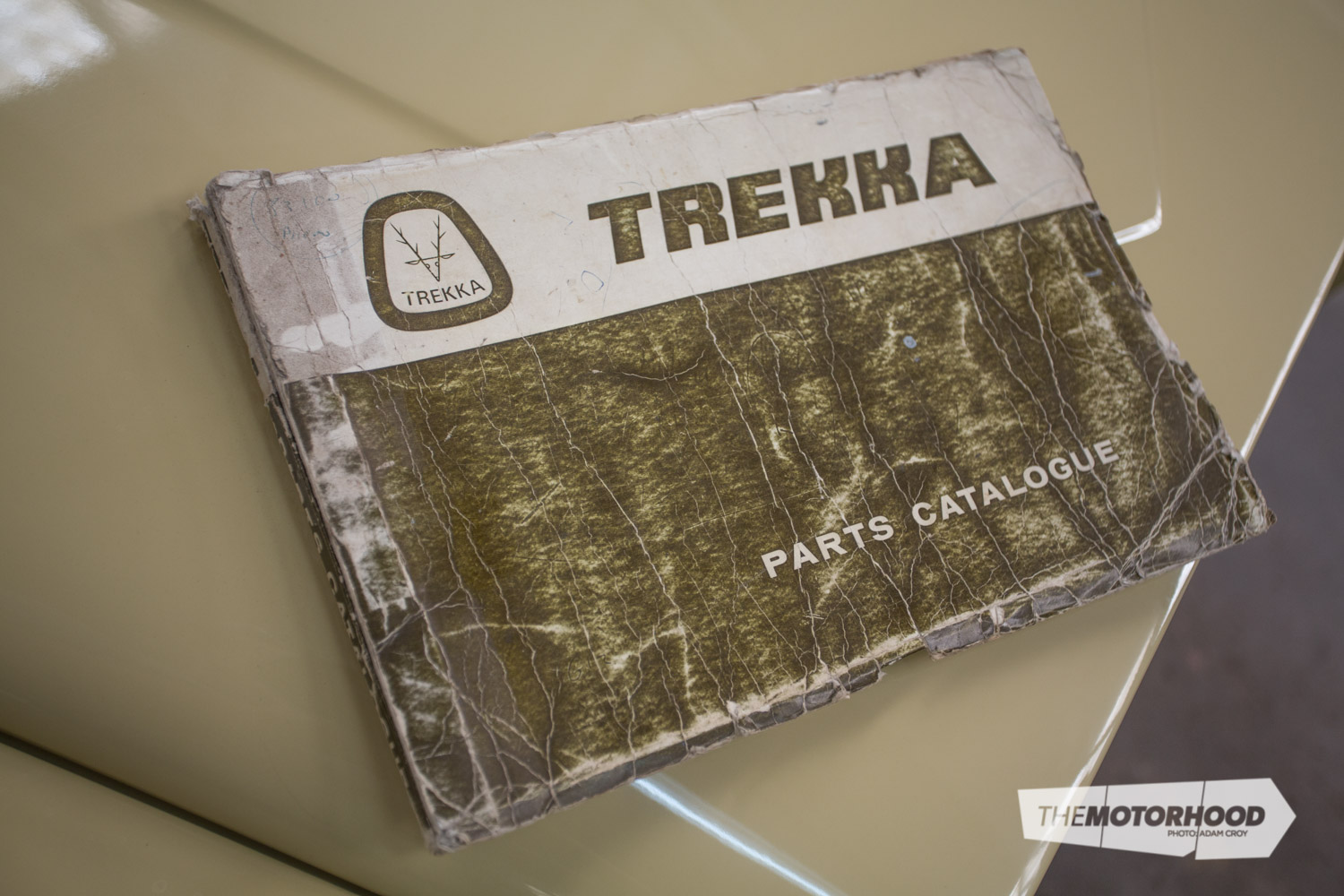

After finding a good project, Tony’s next mission was to track down as many good spare Trekka parts as he could find. As luck would have it, he met John Bailey from Matamata, who had bought all the NOS Trekka/Octavia parts from Gee Motors in Napier about 20-something years ago, and had been supplying parts to Trekka enthusiasts ever since.

After a couple of visits, Tony bought John’s entire remaining stock for the grand total of $1200. This included new suspension parts, carburettors, steering boxes, two dozen brand-new hubcaps and new badges. In short, everything he needed for his restoration. He now had the ideal Trekka and all the necessary bits, and it was time to commence work.

This Trekka is called a long wheelbase 3-18. According to Tony, halfway through the production run a decision was made to chop the back off the Trekka and put a flat deck on it. So, it’s a factory deal.

You could buy the Trekka in three forms: no roof and no tray, roof and no rear tray, or roof and factory tray.

Tony’s Trekka was originally supplied with a roof and no rear tray. The tray was built and fitted by the owner in Invercargill. It was quite comical, because the wheels had travelled so high that they had worn holes in the deck — clearly it wasn’t a particularly successful vehicle for carrying excessive loads.

When Tony was following up on some information from Graham Lambourne, in Wainuiomata, they got talking about Trekkas and Kiwiana when Graham said, “I’ve got a Trekka under the tree, you’re welcome to have it if you want it.”

It just so happened that Graham’s example was identical to the Trekka Tony was restoring, complete with an original factory tray — naturally, Tony took Graham up on his offer. However, when he got it back to Auckland, the Trekka’s decking and bearers were too rotten to use, though luckily the steel under-structure was intact. Just by chance Tony then met a boat restorer, Mark Stapleton, and he volunteered to restore the tray using tongue and groove timber. Subsequently, Mark reconstructed the lower structure exactly as original, and also managed to save the original drop-side and tailgate panels so they could be reused. When Tony saw the quality of the craftsmanship, he couldn’t pay the money fast enough.

The Trekka’s steel mudflaps were completely rusty, and Tony had to fabricate new items, including stay bars and fittings exactly as per the originals. They were also painted correctly. Tony points out that the inside of the bearers are black and the outside is body colour, exactly how they left the factory. All the hardware, the hinges, chains and latches that were taken from the Trekka from Wainuiomata were cleaned and galvanized before fitment to Tony’s vehicle.

Early Trekkas also had two small Sparto-pattern stop and indicators on the back. The second run of production vehicles used a Britax combination lamp, one change that’s noticeable on the later Trekka.

The Trek concludes

The body itself also required attention. Tony owns Custom Metalshapers Ltd, and spends his days working on high-end restoration projects such as Aston Martin, BMW and Jaguar. As such, the simpler construction of the Trekka made it relatively straightforward for him to refabricate and fit a new front valance as well as the area above the windscreen frame, the latter a region where condensation had collected over the years. Tony also points out that the big problem with the Trekka is that they were never painted on the inside, causing them to rust from the inside out.

Tony also fitted a replacement right-side front guard, a panel taken from an old Trekka he’d purchased for $200 — the only decent salvageable part on that car. The only other task necessary was to fabricate and fit new lower door skins.

All the suspension was stripped down to reveal a totally bare chassis. The chassis was then blasted and painted black, while all the suspension parts were also blasted, painted black, and reassembled with new bushings all the way through.

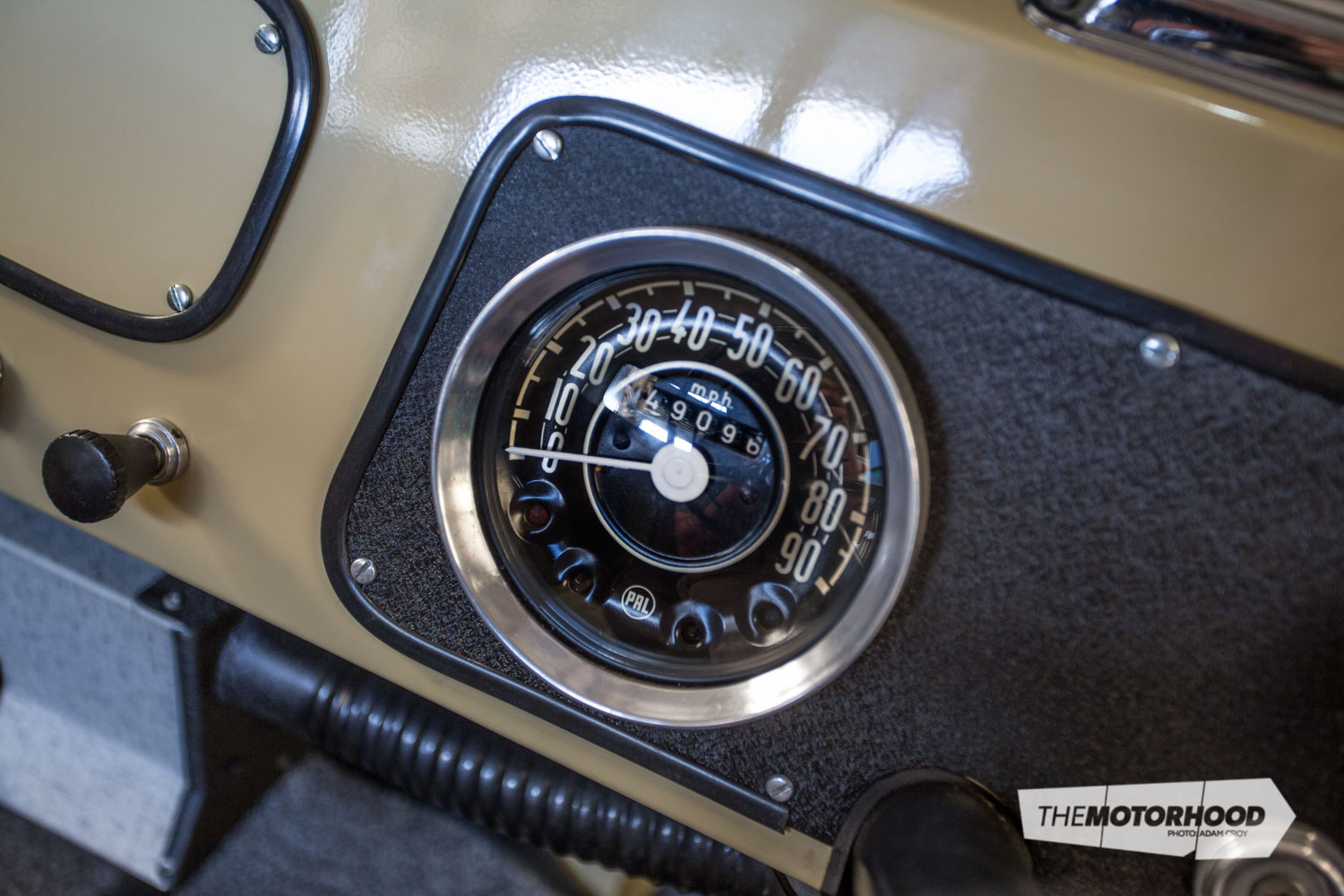

New brakes were installed, and the engine was cleaned and detailed. Tony thinks it will probably require a rebuild at some stage, and had the radiator serviced and retaped the wiring loom. New glass was cut and installed along with new seals. The fibreglass roof was tidied and repainted with a satin finish to replicate the original cream gel-coat. Interestingly John Lisle from Cascade Auto Finish, who painted the Trekka, used to work at the factory, not on the Trekka line but just after the Trekka. Another original Trekka employee reconditioned the handbrake cables. He worked at the Trekka factory as part of the team that redesigned the handbrake assembly — the initial design being a really horrible old Eastern Bloc set-up, according to Tony.

The paint supplier also told Tony of his many fishing trips in a mate’s Trekka — he and his fishing buddies would pop off the hubcaps and cook up the fish in them over an open fire, so there’s been a lot of reminiscing and Trekka stories along the way, most of them favourable.

Tony had the seats retrimmed by Classic Upholstery in East Tamaki. They also carried out some research on what carpet was originally used on the gearbox cover, and managed to find speckled gray carpet to match the original.

All in all, the restoration was quite a simple job — one of the reasons Tony likes military and commercial vehicles. There’s minimal chrome, no wall-to-wall carpeting and hood lining, or loads of extras that now cost thousands and thousands of dollars to restore. These vehicles can be restored economically, and they’re as much fun as anything else to drive. In fact, Tony already has plans for his next project, a canvas-top Trekka wagon. He reckons there are still plenty of spare parts left over for at least one more, so it’s just about clearing some space and getting onto it.

Now, where have we heard that before?

The Trekka 1966–1973

- Engine: Skoda inline four

- Capacity: 1221cc

- Bore/stroke: 72mm x 75mm

- Comp ratio: 7.5:1

- Max power: 35kW at 4500rpm

- Transmission: Four-speed manual

- Suspension F/R: Independent by coils springs/independent swinging half axles. Optional LSD

- Brakes: Drum/drum

- Wheels/tyres: Pressed steel/5.90 15-inch

- Overall length: 4065mm

- Width: 1549mm

- Height: 1867mm

- Wheelbase: 2400mm

- Kerb weight: 907kg

- Production: 1966–1973: c. 3000

This article was originally featured in a previous issue of New Zealand Classic Car. Pick up a copy of the edition here: