data-animation-override>

“Some cars from the ’80s and ’90s are now approaching classic status and we take a look at some of them”

Most Porsche purists will tell you that a front-engined Porsche simply isn’t the real thing — if it doesn’t have a rear engine it just can’t be a Porsche. I say let the purists have their opinion because that means that in the second-hand market, front-engined Porsches represent a genuine bargain compared to their rear-engined brothers. And due to their far better weight distribution, Porsche ‘fronties’ are also less likely to bite back at inexperienced drivers.

So, what are the choices? Well, there’s always the V8-powered 928, a big and heavy car best suited to long distance work. However, although 928s can now be picked up very cheaply, ongoing costs may be very high.

Even cheaper to buy is the 924 – although it’s hard to find examples which haven’t been thrashed to death and, with the best will in the world, the 924’s VW-Audi engine is hardly a paragon of either power or civility.

A far better option than either of these is the 944, a car conceived to replace the 924 as Porsche’s entry-level model and, unlike the car it was based on, the 944 is at least powered by a genuine Porsche motor. In S2 Turbo form, a well-driven 944 was easily capable of seeing off most 911s.

Entry-level Porsches

Some would see some irony in the fact that Porsche — with its first car essentially a derivation of the quintessential ‘peoples’ car’ — didn’t actually attempt a low-price, entry-level car itself until 1969. That model was, of course, the VW-Porsche 914. The 914, available in 1.7, 1.8 and 2.0-litre form, didn’t go down too well with Porsche die-hards, who disliked the basic VW 411 engine and its mid-mounted position. Perhaps they’d forgotten Porsche’s VW antecedents or, more likely, didn’t want to be reminded of them!

Of course, to many a mid-engined sports car seemed rather more practical than one with an engine dangling over its rear axle. However, not everyone felt that way, and Porsche was able to unload over 115,000 914s from 1969 to 1975. It even attempted to upscale it by fitting the then current 911T six-cylinder engine for the 914/6. Alas, that model was a bit of a sales disaster, with only 3332 examples being sold between 1969 and 1972.

Once the 914 had bowed out in 1975, Porsche was back to a single model again; the 911. And, although it probably hadn’t intended to produce another entry-level model, other factors made Porsche change its mind.

VW-Porsche Vertriebsgesselschaft

In 1972, VW-Audi approached Porsche with a view to having it design a new sports car utilising standard VW and Audi parts. Accordingly, Porsche came up with a fairly conventional front-engined, water-cooled car, but opting for RWD rather than the FWD configuration preferred by VW-Audi. It also specified a rear-mounted transmission — transaxle — for improved handling balance and weight distribution.

The new car had been planned to carry an Audi badge, but the oil crises of the ’70s put it off producing a wasteful sports car. So, rather than waste all that effort, Porsche took over the car and the 924 was born, with production commencing in 1976.

Once again, die-hard Porsche traditionalists were horrified — and this time, they were also confronted by a water-cooled car, a major break with Porsche’s established air-cooled philosophy. To many enthusiasts, the new car was simply not a genuine Porsche — but that didn’t stop the 924 becoming the brand’s top-seller.

However, while there was no doubt of the 924’s sales success, what Porsche needed was an entry level car with a bit of pedigree — in short, a 924 with a ‘proper’ Porsche engine.

From 924 Carrera GT to 944

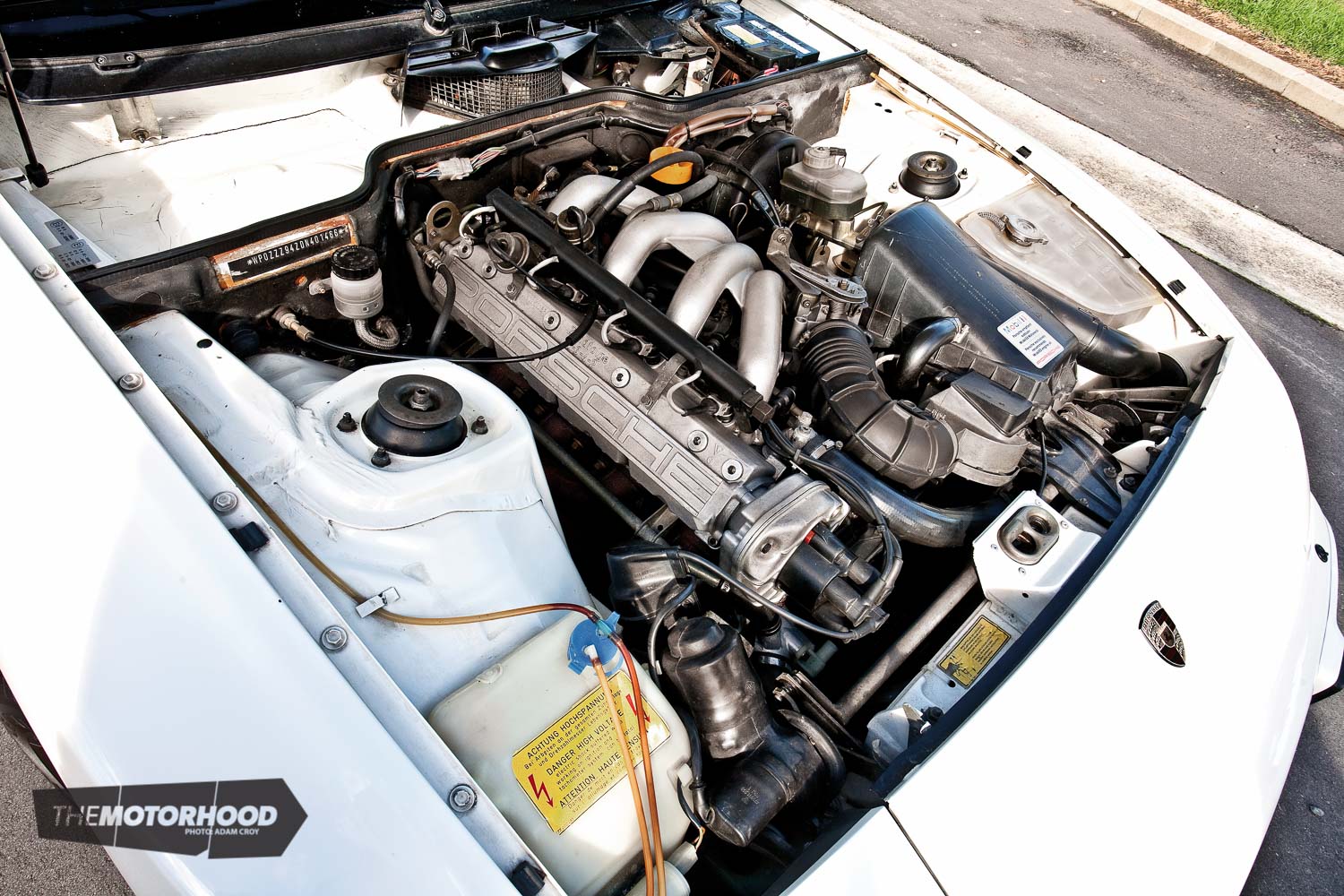

In essence, Porsche simply chopped one bank of the 928’s V8, which left a 2.5-litre, all-alloy four-cylinder engine — although very few parts were interchangeable between the two motors.

Large capacity four-bangers are not renowned for being particularly smooth, so Porsche chose to fit the new engine with two counter-rotating balance shafts to smooth out engine response. Although this type of engine balancing measure had originally been devised by Frederick Lanchester in 1904, the idea had been developed and patented by Mitsubishi – which meant Porsche was forced to pay a licensing fee to the Japanese automaker.

With the engine finalized, Porsche then did what it has always done best – take an existing car and further develop it, something it had done with the 356 and, of course, at that time was continuing to do with the 911.

The 924 platform was completely revised, including improved suspension and braking. When it came time to design the new car’s body, Porsche looked at the 924 Carrera GT – a limited edition version of the 924 which had featured a radical plastic body kit, including bulging wheel arch extensions. With a few revisions, the 944’s body was basically a redesign, of steel, of the Carrera GT.

With the addition of an all-new interior and better equipment levels, the Porsche 944 made its debut in 1982.

944 variations

With a wider track that the old 924, the 944 was inherently the better-handling car and also featured much-improved performance — although the early, normally aspirated 944 was marginally slower than the outgoing 924 Turbo.

With its butch, flared guards and low stance, the 944 also looked more aggressive and muscular than the slightly effete 924.

The first 2.5-litre 944 models arrived in New Zealand during 1982, with the base car gaining a larger, slightly more powerful 2.7-litre engine in 1989.

During 1986, Porsche introduced the first serious 944 performance derivation with the 944S. Eschewing the base SOHC engine, the S was fitted with a more powerful, 16-valve twin-cam engine. The car’s chassis needed only a few changes to handle the extra urge, and in 1989, with the introduction of the S2 model, engine capacity was increased again, this time to 2990cc, while wheel size went up to 16 inches. The new S2 was also available as a convertible for those who preferred open-air motoring.

Meanwhile, the first turbocharged 944 made its appearance in 1985. Porsche fitted a KKK turbo and a Bosch engine management system to the single-cam 2.5-litre engine, tweaking it to produce a healthy 164kW. Interestingly, the 944 was the first car ever to use a ceramic port-liner to retain exhaust gas temperature. In order to get the best out of the improved power, Porsche strengthened the gearbox, stiffened up the car’s suspension and added wider, 16-inch wheels – seven inches up front and eight at the rear. Oil coolers were also fitted for both transmission and engine.

The S2 Turbo received a larger turbocharger, a revised camshaft, even wider rear wheels and a limited-slip differential to better handle the new output of 187kW. Easily identifiable through their twin cooling slots up front, the S2 Turbo was listed at close to $180,000 when new. A turbocharged cabriolet was introduced in 1991 — Porsche originally only intended to produce 500 of these models but, by the time the limited production run was complete, 625 had been built.

Other changes included the addition of anti-lock braking in 1987 — which meant the traditional Fuch alloy wheels were no longer available for the 944. In the same year, dual front airbags also became a standard fitment — another production car first.

By the early ’90s, Porsche was already working on a third evolution of the 944 but, as development work progressed, what had originally been intended to be the 944 S3 eventually became a 944 replacement — the 968. Porsche discontinued 944 production in 1991, with the 968 appearing the following year.

On the road

Step into any 944 and, like all Porsches, the driver is confronted by a relatively plain interior – don’t expect any TVR excesses! The later, so-called ‘oval dashboard’ cars look better, but the look is purposeful rather than dramatic.

As well, having morphed from the 924, the 944 inherited that car’s rather low steering wheel. In truth, it’s not as badly sited as it is in the 924, but taller drivers will still find their legs getting in the way when at the wheel.

However, these are all minor points and, as a whole, the 944 makes a good compromise between handling and ride comfort — it is neither too hard to be uncomfortable over long journeys, or soft enough to roll during hard cornering. Even drop-top versions are little compromised by loss of rigidity, proof of the 944’s solid construction.

Early normally aspirated cars have to be rowed along through their gears; the 944’s big four-banger is a peaky motor, and you need to work hard at it in order to release the performance that’s available. This engine thrives on being given the whip, so don’t spare the revs.

By comparison, later multi-valve engined cars offer more power, more easily accessed while the S2 cars are the nicest to drive and the last-of-the-line 3.0-litre cars – with their extra helping of torque – are great city-to-city GTs. Of course, for outright power the Turbo – especially in S2 guise – is a real road-burner, easily capable of seeing off a modern Boxster S.

Whilst designing the 944, Porsche ensured good weight distribution by mounting a torque-tube running from the engine to the transaxle gearbox mounted at the rear. It’s a system that works very well, gifting all 944 variants with well-balanced handling. Equally, steering featured good weight and feel and, along with the 944’s excellent weight distribution and secure braking, it all makes for very neutral handling, pinpoint steering precision and rapid on road progress. In short, a well sorted 944 is a joy to hustle along quickly.

Buyers guide

Like most Porsches, the 944 features excellent build quality and largely due to this, this is one sports car that is quite happy to be pressed into use every day. Of course, this does mean that many 944s will now have completed high distances — and, as major mechanical work can easily exceed the purchase cost of a tired example, its essential to select a car with a comprehensive service history. At the very least you need to ascertain that the car’s engine has been properly maintained. For example, rubber timing belts should be replaced at least every 80,000km. Belt failure can result in catastrophic engine damage.

Engine mounts should also be checked, as those on the exhaust side have a tendency to fail due to excess engine vibration at idle. Water pumps should also be checked carefully, as if the pump fails it will seize the timing belt and damage the engine. Alas, the 944’s water pump is not easily accessible and replacement is definitely a specialist operation.

Steering fluid reservoirs are also known to be prone to leaking due to poor hose clamps while, especially for cars that have resided in New Zealand since new, dashboards can split.

Turbocharged 944s are fitted with a small pump that continues to pump coolant after the engine is shut down. You should be able to hear the pump whirring for around 30 seconds after turning off the engine — if you can’t hear anything, a replacement pump will be required.

However, if properly maintained the 944’s engine is capable of achieving huge distances and, with its fully galvanized body, rust will only be a problem on accident-damaged cars that haven’t been repaired correctly, or on severely neglected examples.

Although it’s possible to pick up an early 944 for less than $10,000, buyers need to be aware that a cheap purchase price doesn’t mean you can get away with cheap servicing — it’s still a Porsche! Indeed, anyone contemplating a 944 would be best advised to have any potential purchases checked out by a recognised Porsche specialist.

When it comes to picking a 944, the later S2 models are generally considered to be the best, with the Turbo models and convertibles being the most collectible – and, of course, the most expensive.

Price range for the 944 runs from below $10,000 for normally aspirated S1 car with a high odo reading, up to $15,000 to $20,000-plus for a well maintained S2, with good Turbo and cabriolet models starting at the higher end of that price range. If you are lucky enough to find a rare, low mileage 944, expect to pay an appropriate premium.

Parts and servicing

Even though these are not expensive cars to buy nowadays, the 944 is still a high-performance sports car and needs appropriate servicing — and, if you don’t want to compromise the car’s handling and performance, that means genuine Porsche parts. You also can’t stint on perishables, such as tyres.

On the plus side, there’s no shortage of parts for the 944, with these available either from official Porsche dealerships or through several independent Porsche specialists.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 235. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: