data-animation-override>

“This Rover SD1 has been part of Michael Ahie’s family since his grandfather drove it off the showroom floor over 30 years ago. He shares the story of returning the Rover to its former glory”

The bright-metallic-green Rover SD1 looked like something from outer space — well, it did to me when I first saw it at the end of our driveway with my grandfather at the wheel.

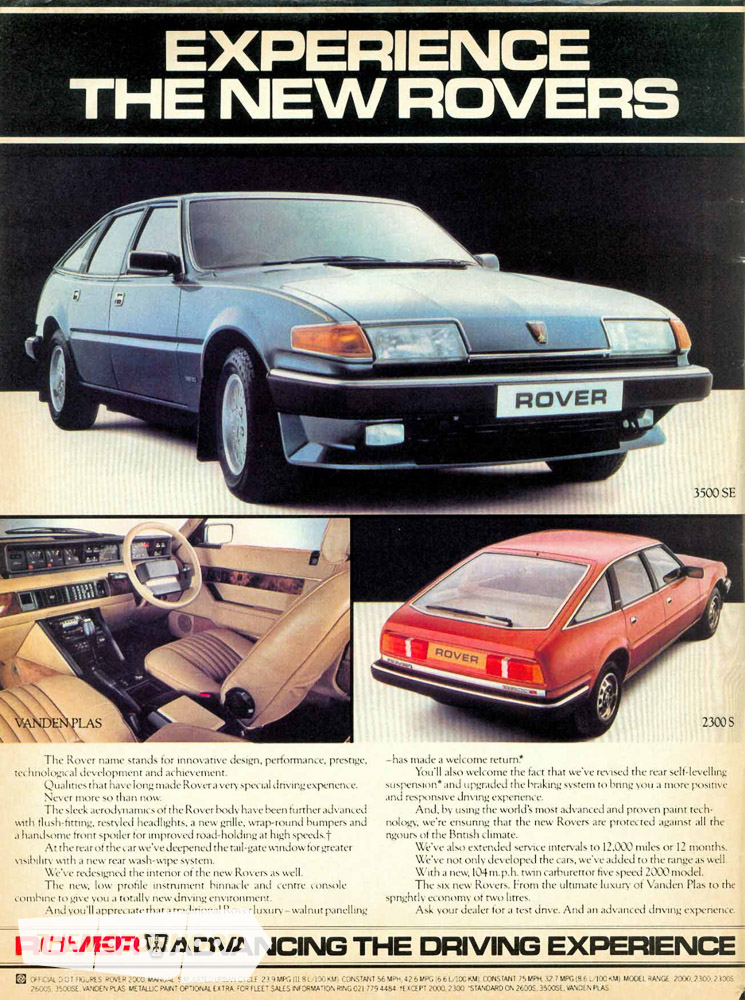

Growing up in a small rural community in Taranaki in the 1970s, my grandfather’s new Rover SD1 caused quite a stir when it was first sighted in Opunake. It was 1979, and I was 13 years old. In those days, my dad drove an HG Holden ute and my mum, a Vauxhall Chevette. A Rover SD1 was very exotic in small-town New Zealand back then.

My grandfather was known to everyone in town as ‘Jim’, and to all his whanau as ‘Pa’, and, when he pulled up at the end of our driveway in that space-age Rover SD1, I was hooked. He took me for a ride. I’ll never forget that first cruise down Tasman Street, with him at the wheel, and me looking at all the gauges and switches and listening to the purr of the engine. My love of cars was well on its way to full obsession. My grandfather owned an SD1! This meant immediate street cred to me, his grandson.

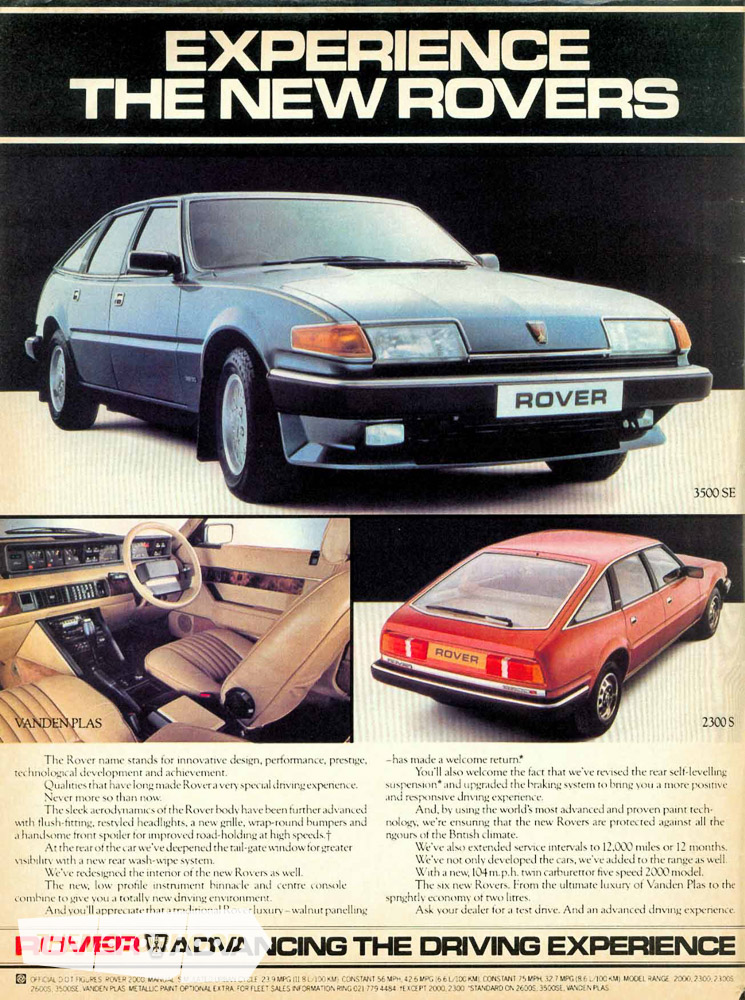

A few years later, Pa bought another Rover SD1, registration number MG261. This time, it was the top-of-the-range 3500 Vanden Plas, the Series II version lavished with everything 1980s technology could offer: air conditioning, headlight washers, electric and heated mirrors, fog lights, power steering, central locking, electric windows, an electric sunroof, a leather steering wheel with tilt-and-reach adjustment, front and rear reading lamps, a burr-walnut fascia and door inserts, rear passenger heating, an Alpine radio/cassette with four speakers, tinted glass, a front spoiler, and — my favourite feature — a trip computer with a stopwatch and … a 240kph speedo. Wow.

By this time, I was at university and didn’t see my grandfather as much. It was the last Rover he owned, and, after his passing in 2002, it sat, a little forlornly, under a few blankets in a shed on our farm back home.

Alice

In 2007, I was standing around the car with my uncles, Terry and Joe, and I (quite innocently) asked, “What are we going to do with that?”

Uncle Joe replied, “You want to take it home with you?” I lived in Wellington. I said, “Really?”

“Really,” he replied, “and bring it back when you’ve had enough of it.”

That was the start of an eight-year restoration project.

It was my grandmother who actually wrote out the cheque to buy MG261. My cousin Nicola found the original purchase receipt in some old files. My grandmother’s name was Alice. She always had a blanket over the back seat to protect the velour, and would often sit in the back with an eye on the speedo; Jim got a short sharp order to slow down if the needle even approached 101kph.

‘Alice’ is what I call the car now; it seems to fit.

In mid 2007, I went back up to the farm to trailer the car to Wellington. I found it to be in a sorry state. Eight years of sitting idle had not been kind. A family of mice, long deceased, had made a right mess of the interior. It stunk, and there were nests in the dash where the clock used to be. The registration sticker on the windscreen had an expiry date of February 1999. Anyway, after a jump start, it fired into life remarkably easily, and I drove it onto the car trailer — after a quick squirt up Opua Road, just for old-time’s sake.

Sentiment

In late 2011, I rang my dad: “Dad, I’ve still got Pa’s Rover in the garage.”

“I know that, son.”

“I’ve done the sums, Dad. It will cost me heaps to fix it properly, and it will be worth less than restoration cost, and I’m feeling guilty about it, and Janine’s car is outside and I haven’t got time, and …” On and on I went, with a long series of excuses.

“Well, sell it then,” he said. There was a long pause.

“I can’t sell it, Dad! It’s the last car Pa ever owned!”

Another pause. “Well, fix it then,” he said.

And that was that. Decision made — restoration was to commence immediately.

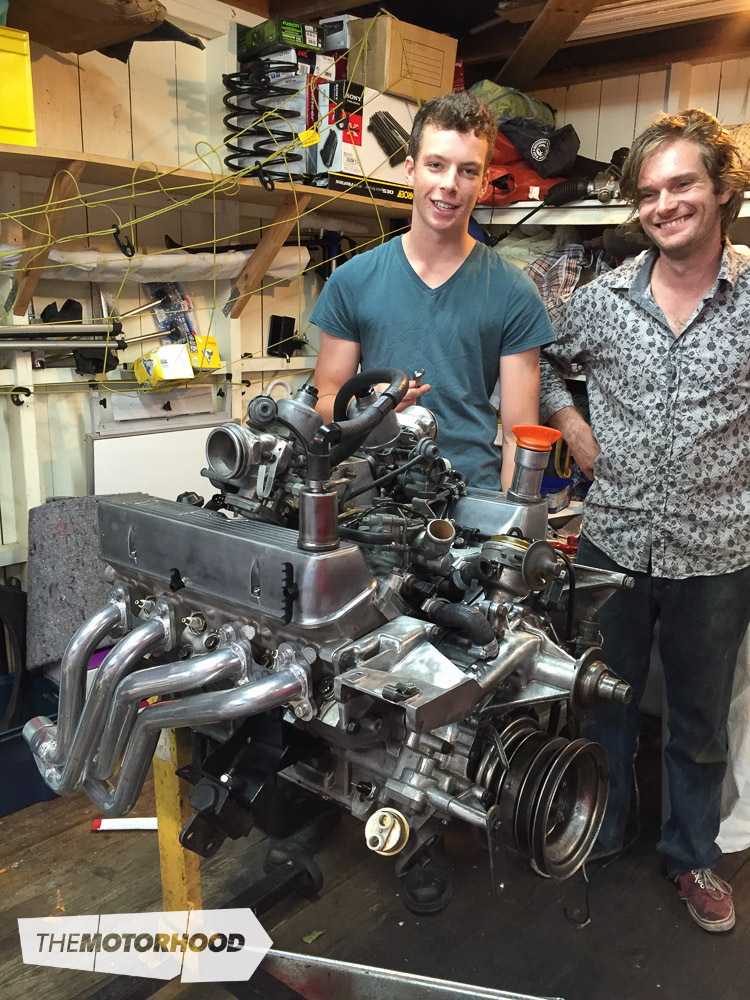

Disassembly started on Saturday, February 4, 2012. On the team that day were my dad and my sons, Sam and Joe, who were 14 and 11 at the time.

Over the next six weeks, we worked every weekend and a couple of nights each week to fully strip the car. Tuesday night became the unofficial ‘Rover Night’, and mates and family members showed up to help out.

On Sunday, March 18, 2012, it was done, and we secured everything ready for the transporter to take the body shell to Mike Baucke and the team at The Surgery for the panel and paintwork. I had started a diary of all the work, and recorded the hours done, and by who. The total disassembly time was 105 hours.

Spectacular result

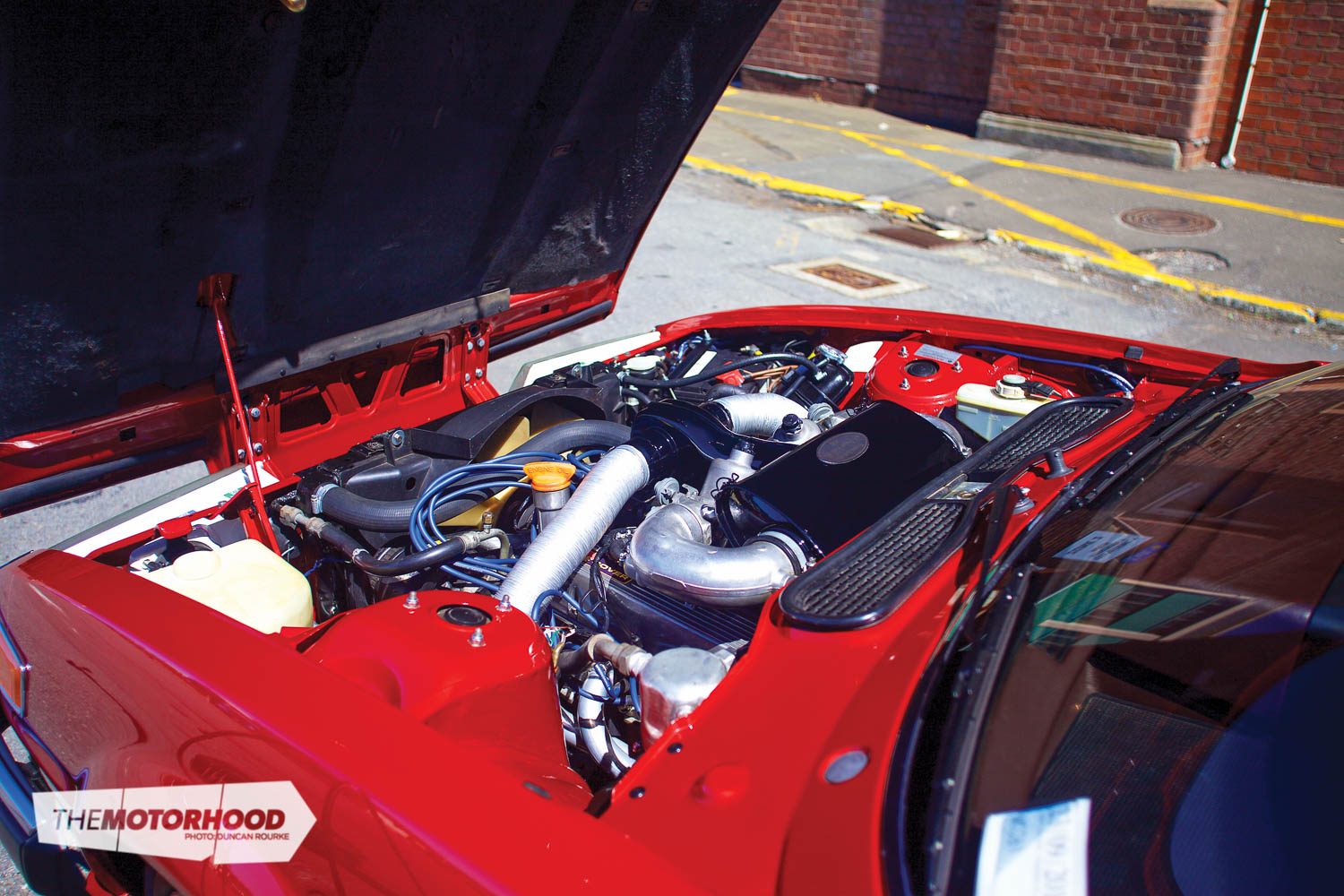

On Friday, November 23, 2012 the body shell came back from The Surgery. It looked amazing in its new coat (well, many coats) of Burgundy Mica Pearl. It was hard to believe it was the same car. I had given Mike a challenge with the paint specification and the finish I wanted, plus every single panel had a war wound of some kind. The finished result is a tribute to the panel accomplishments of the team at The Surgery and to Mike’s painting skill. The restoration team members were all very nervous about the rebuild — no one wanted to be the first to mark the perfect paint!

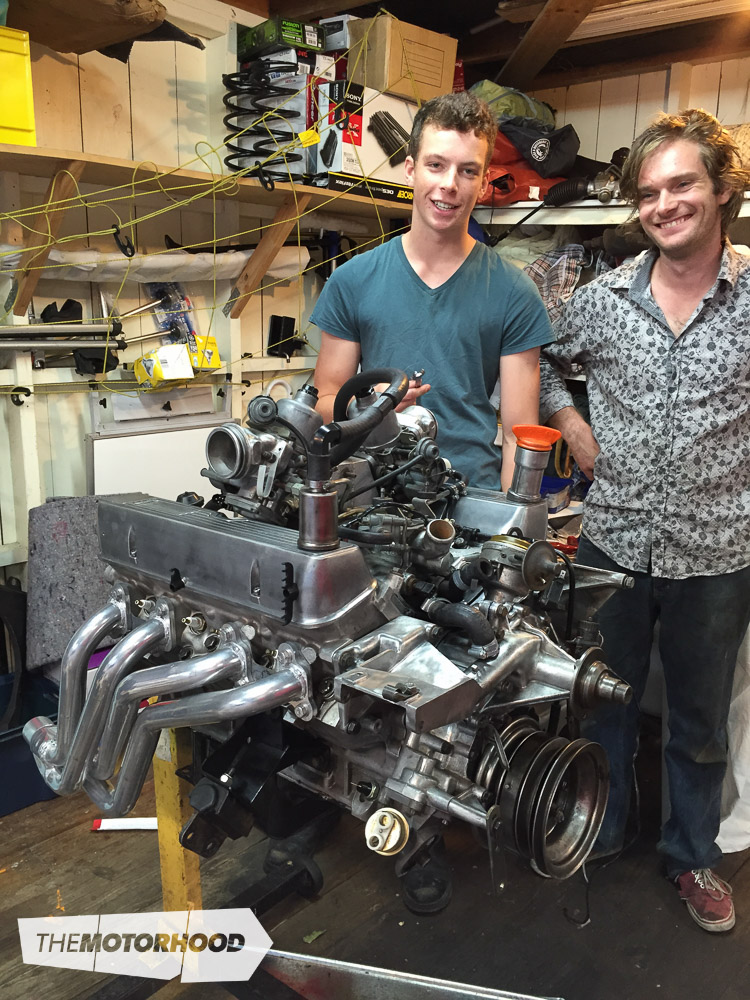

I needed an experienced mechanic to help out with some of the technical bits, and I was keen to have someone to mentor Sam, who wanted to rebuild the engine. I asked around, and Roy McGuinness put me onto a young chap named James Davison. Roy said he knew a thing or two about Jags and Rovers, and might just be prepared to join the Tuesday Rover Night crew. I met James, and things just went from there. He has been a major part of the build from day one.

He and Sam hit it off from the start, and their banter and general hilarity made the project a lot easier — those who have attempted a major restoration like this will know that motivation can wane at times; these two blokes kept me going, that’s for sure. The energy of this duo created one very exceptional Rover V8 engine.

The restoration carried on in earnest through the rest of 2012 and into 2013. In 2014, the SD1 took a back seat to another car project, then things got back underway in early 2015.

Dad and I decided we needed some more expertise to help us cross the finish line. I placed a ‘Help!’ call to Andrew Fox at Classic and Modern Motoring. He came over that afternoon.

Andrew has worked on our classic cars over the last 13 years. He became ‘Chief Drivetrain Finishing Officer’. With Andrew’s help, we sorted the last clutch, gearbox, and exhaust issues. We were ready for ignition.

The first engine start was on Thursday, August 6, 2015. It was a nerve-racking experience for me. Engine builders James and Sam didn’t seem too worried — they had confidence in the build, obviously! It all went well, other than the fuel pump failing after sitting around in the fuel tank for 16 years doing stuff-all — somehow, James procured a new genuine replacement one within two hours. We had fuel, spark, and plenty of oxygen-rich Wellington air. The fresh Rover V8 fired up. It was a very special day for me.

The test drive round the block was event-free. James monitored engine functions. I couldn’t get the smile off my face. It ran perfectly. After 1700 labour hours, three-and-a-half years, some challenging days and nights, and a few laughs, too, it was done. Jim and Alice’s SD1 is back on the road, and she looks spectacular.

1985 Rover 3500 Vanden Plas (SD1)

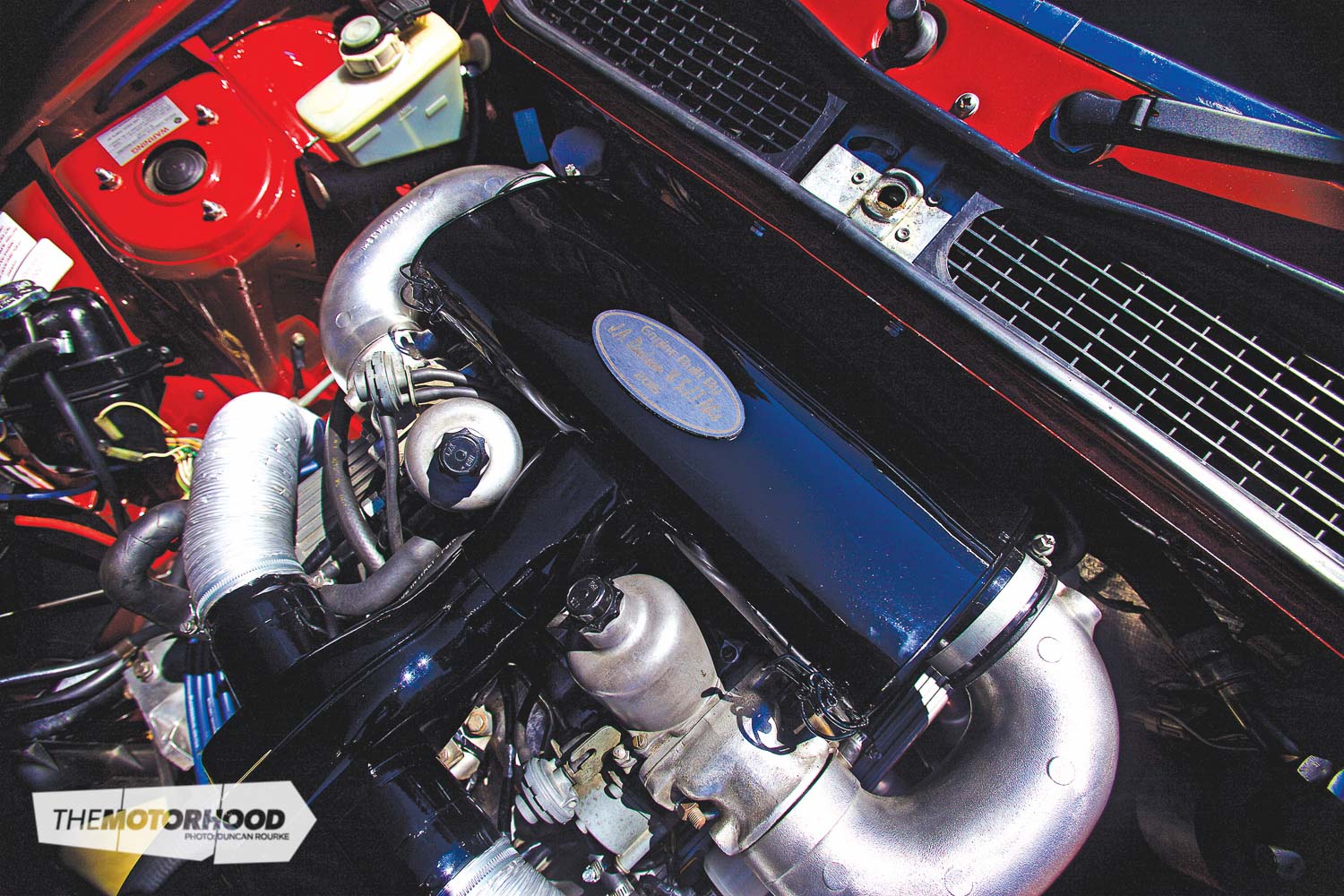

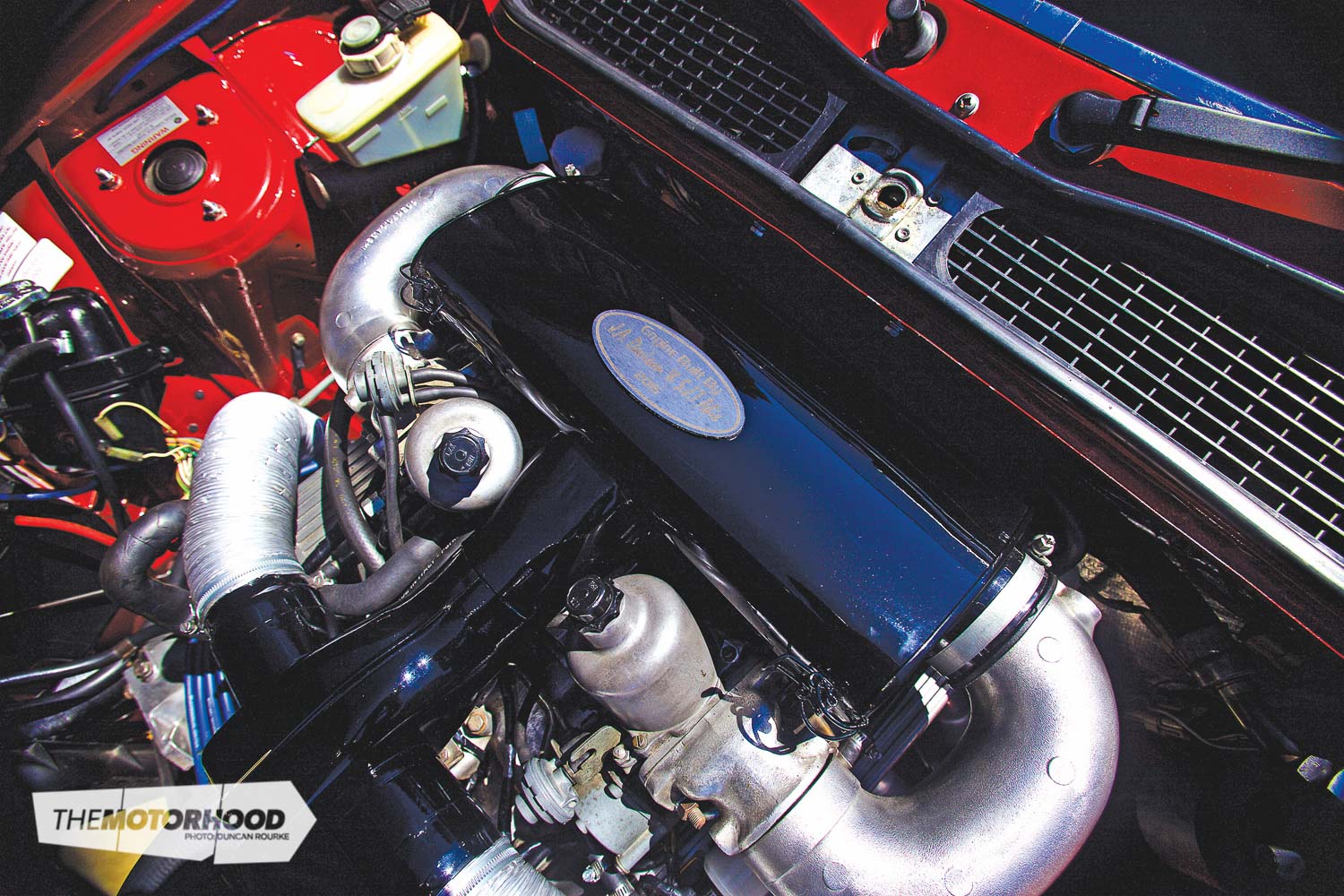

- Engine: Type 16V, aluminium-alloy V8

- Capacity: 3528cc

- Bore/stroke: 88.9×71.1mm

- Comp. ratio: 9.35:1

- Fuel system: Twin SU HIF 44E with electronic fuel management

- Max power: 116kW (155bhp) at 5250 rpm

- Max torque: 268Nm at 2500rpm

- Transmission: Five-speed manual, aluminium-alloy (W55 series)

- Suspension: F/R MacPherson strut with coil springs and anti-roll bar, Rover Vitesse–specification springs, and dampers / Live-axle with coil springs, semi-trailing arms, torque tube, Watts linkage. Rover Vitesse–specification springs and dampers

- Steering: Power-assisted rack-and-pinion; turning circle 10.4m, 2.7 turns lock-to-lock

- Brakes: F/R 258mm ventilated-disc with four-piston calipers / 228mm drum, self-adjusting

Dimensions:

- Wheelbase: 2814mm

- Length: 4740mm

- Width: 1765mm

- Height: 1384mm

- Fuel capacity: 65.9 litres

- Kerb weight: 1458kg

- Performance:

- 0–96kph: 8.4 seconds

- Max speed: 201kph

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 303. You can pick up a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: