Back in 2015, we spent a week in the Queenstown area. We got to meet some wonderful and very friendly classic car owners keen to share their vehicles with us.

This very rare Packard — a 1932 Packard Sport Phaeton Model 905 — is part of the Warbirds & Wheels collection at Wanaka.

This Packard spent much of its life in Wichita, Kansas. On its initial delivery, the car was fully optioned with such features as the dual-cowl windscreen, front spotlights mounted by the windscreen, and twin side-mounted spare wheels complete with twin-mounted rear-view mirrors. Also fitted was a Packard cormorant hood mascot, radiator-cap stone guard, driving lights, and a trunk.

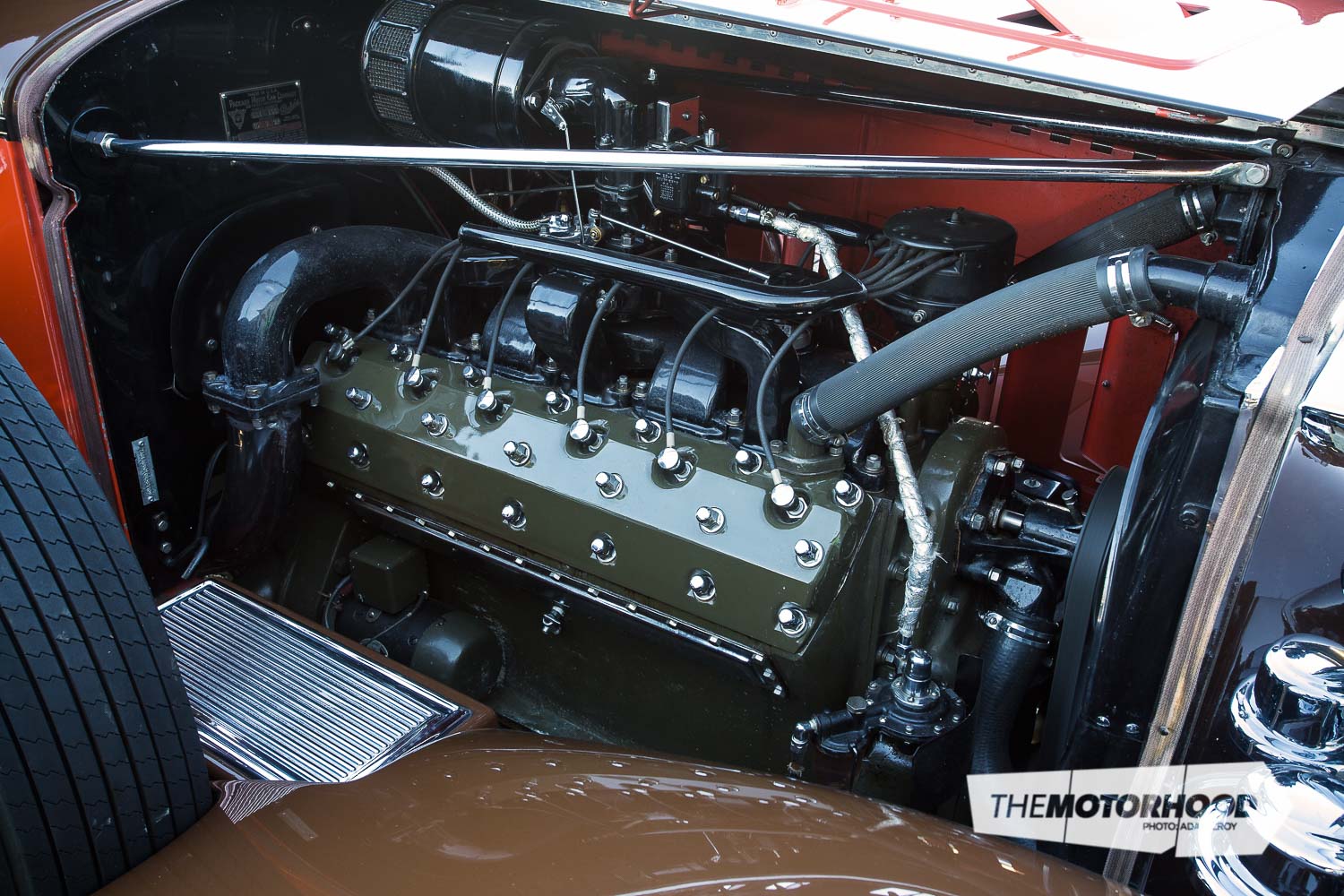

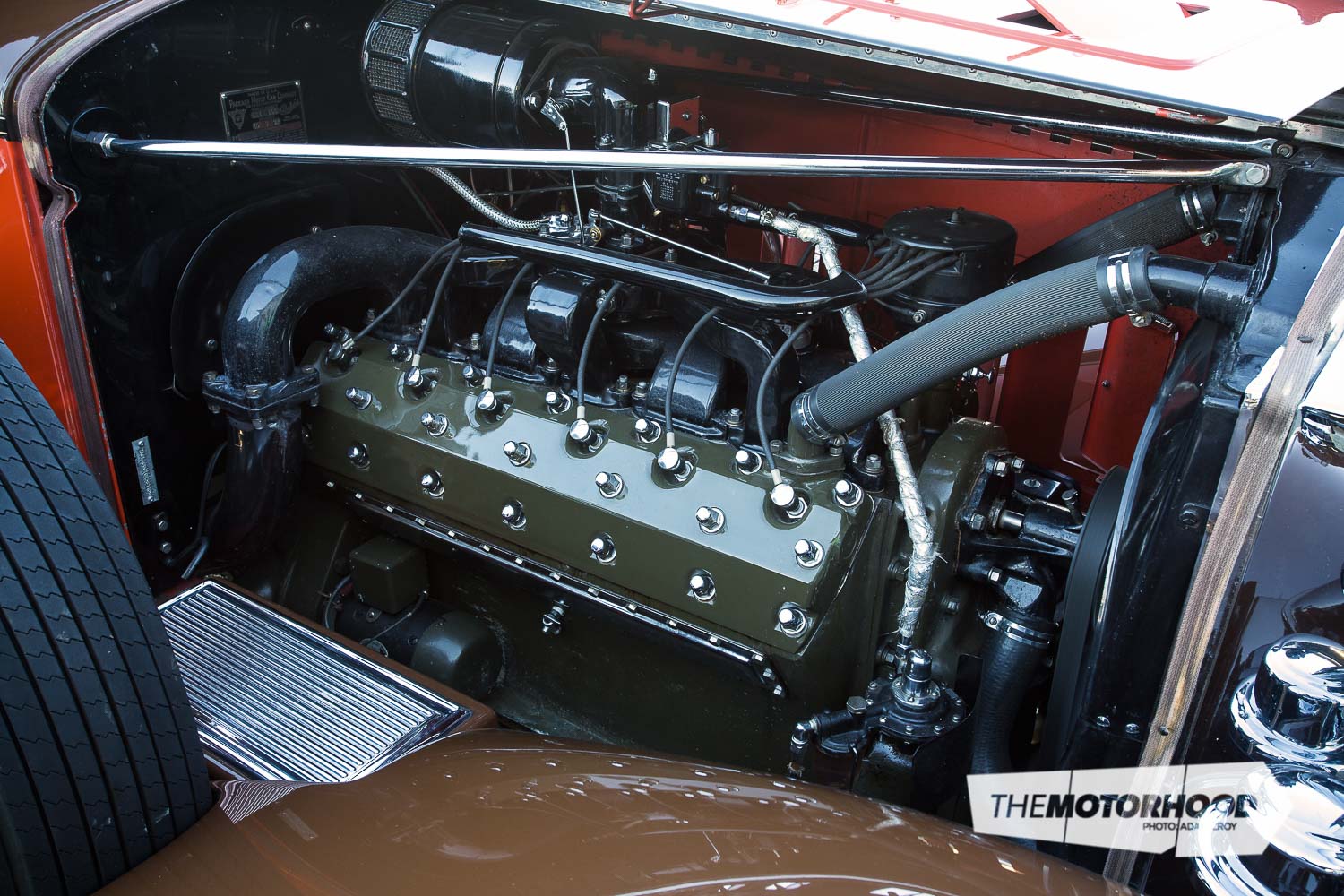

Eventually, the Packard ended up on display in a private museum, a stay that lasted for about 15 years, during which time its massive 7.2-litre V12 motor was never started.

Warbirds & Wheels

Acquired for the Warbirds & Wheels collection, the Packard arrived into New Zealand in 2004. Upon closer inspection it was discovered that most of the internal engine components were quite solidly gummed up, so the decision was made to completely dismantle and refurbish some of the mechanical engine components before reassembly.

Interestingly, a small oval plaque mounted on the car’s firewall, and originating from the Classic Car Club of America, records the ocassion when this Packard won the Colorado Glenn Grand Classic in 1982, scoring an impressive 98.5 out of a possible 100 points. Apparently the car had just been fully restored at that time. There’s also a number on the plaque, which bestows senior status within the Classic Car Club of America upon the car.

This Packard is believed to be the only 1932 Twin Six Dual Cowl Sport Phaeton in the southern hemisphere — not surprising when you consider that only eight were ever built with this Raymond Dietrich–designed body.

This car has been fitted with an aftermarket overdrive unit to augment the original three-speed transmission, to keep engine revs as low as possible at cruising speed. The car is very easy to drive, and will sit quite comfortably at 100kph all day long, with the massively torquey V12 engine ticking over like a Swiss clock.

And now we’ve mentioned the Packard’s magnificent engine, we should note it has been said that the introduction of the V12 Packard was partly responsible for the eventual demise of the Duesenberg. The Duesenberg, produced by the Auburn Cord Duesenberg group, was the most expensive car available (at US$17K) in its day. However, on introduction, the asking prices for V12 Packards ranged from US$4K upwards, though it is believed the new price of our fully optioned feature car was probably closer to US$5K. The perception from the buying public was that the Duesenberg was not worth three and half times the cost of the Packard.

Enviable reputation

While a Packard V12 model may have seemed inexpensive against a Dusenberg, don’t be fooled into thinking these Packards were in any way cheap or inferior vehicles. Back in the day, Packard had an enviable reputation for building superb-quality cars with outstanding performance. In what can only be described as a blatant display of self-assurance — or arrogance, depending on which side of the fence you sit on — in 1932, Packard, notably undeterred by the Great Depression, unveiled its new Ninth Series, a comprehensive range of luxurious, beautifully engineered cars crowned by the Twin Six, at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City.

The Twin Six showcased Packard’s return into the super-luxury–car market and became its flagship model, a pillar of American prestige boasting an impressive 7292cc V12, producing 119kW at 3200rpm. To combat other rivals within the luxury-car category, Packard hired Cornelius Van Ranst to design a small-bore V12 engine with a narrow, odd, but uniquely compact, 67-degree V block. Fuel was fed into the V12 through modern downdraught carburettors built by Stromberg, these being modified with larger venturis. A zero-lash valvetrain utilized a single, centre-mounted camshaft to actuate practically horizontal valves with General Motors–patented indirect hydraulic tappets. The combustion chamber was partially in the block, giving rise to the description ‘modified L-head’.

The result was an extremely quiet system, with the spacing between valvetrain components reduced to zero. This meant the engine was capable of clocking up as much as 80,000 kilometres before a valve adjustment was necessary. The new unit was Packard’s first downdraught motor and was equipped with an Autolight distributor, Stewart Warner fuel pumps, and an Owen-Dyneto starter and generator.

Interestingly, as originally designed by Van Ranst, and inspired by his previous work at Cord — a company at the forefront of front-wheel-drive car production — his V12 was initially intended to send its power to the Packard’s front wheels through an intricate and extremely complex drivetrain. However, after much testing in a front-wheel-drive prototype, the transaxle system proved to be inherently flawed. This delayed development before the concept was eventually canned, with Packard reverting to a more conventional rear-wheel-drive set-up.

However, with its positive and smooth attributes, Van Ranst’s V12 engine remained, following Packard dropping any ideas of a front-wheel-drive car. Instead, it pressed forward with the model, enlarging the engine to balance one of its existing chassis — that used by the heavier Deluxe Eight.

Another popular feature used by many luxury brands at the time, and adopted by Packard, was an automatic clutch control unit that engaged the clutch when the accelerator was released. This concept, which Packard introduced as its ‘finger control freewheeling’, offered drivers a switch on the dashboard that automatically used engine vacuum to engage the clutch.

It later became an option but was subsequently dropped — in an era of cars weighed down with heavy chassis and powerful multi-cylinder engines, dispensing with engine braking was always going to put a lot of undue pressure on the cable-operated drum brakes prevalent at that time. As such, engaging the freewheel option injudiciously could lead to drivers getting themselves into an out-of-control situation.

Depression-era investment

Packard’s management later explained the rationale behind the new V12, pointing out that the engine had been on the board before the market crash, so it did not represent much of a depression-era investment. Also, the company noted that it had been forced into the production of a multi-cylinder engine by the appearance of the new Cadillac V12 and V16 models, as well as the new Marmon V16, the Pierce Arrow V12, and the new Lincoln V12. All these cars were vying for the few remaining ultra-rich dollars.

Packard simply had to have the cylinders to compete, and so, in the midst of the worst depression in US history, almost every luxury-car company in the world was busy gaining attention by building and unveiling cars that, even today, still rank amongst the most powerful and beautiful examples of automotive art, design, and engineering to have ever graced a showroom.

During the ’30s, custom coach-built motor bodies symbolized wealth and status. Indeed, the Twin Six was instrumental in elevating Packard’s prestige level immensely, by featuring some of the best American bodies — these being provided by companies such as Brewster, Fleetwood, Judkins, and LeBaron.

However, to retain as much bodywork production in-house as possible, for obvious reasons Packard hired the services of Raymond Dietrich to design its own body styles in line with its conservative target market. In addition, Dietrich designed no less than nine flamboyant body styles reflecting the style, romance, and grace of the late ’30s — these models flaunting Packard’s newly created Individual Custom tag.

It’s interesting to note the similarities between the LeBaron body on the Duesenberg and the Dietrich body on the Packard. Raymond Dietrich, Thomas Hibbard, and Ralph Roberts all learned their body-building skills and met whilst working at Brewster Bodies. These three men founded LeBaron Bodies in 1920. Hibbard resigned in 1923 and, a few years later, Dietrich and Roberts parted. Roberts continued to operate LeBaron Bodies, and Dietrich became Dietrich Incorporated and designed the bodies for Packards as well as other brands.

Wealth and status

In a rather cunning move, Packard priced the luxuriously appointed Twin Six model only marginally higher (by US$100–$150) than its Deluxe Eight models, making it an absolute bargain for the luxury-car buyer. But this aggressive pricing structure didn’t quite go according to plan and Packard, along with Auburn, which had also released a V12 during the same era, soon discovered that prospective purchasers were put off by such a low-priced luxury car. This hesitation in the market caused sales of the model to be less than forecast during its introductory season, with only 549 units sold. Packard soon realized its strategic blunder, and raised the price in the following year by a fairly hefty US$500, which drastically improved sales.

Packard built V12 Twin Six engines from 1916 to 1923 and Single Six, Small Eight, and Big Eight engines from 1923 to 1932. When Packard decided to reintroduce the V12 in 1932, it reverted to its old nomenclature and called it the ‘Twin Six’. However, this led to buyers assuming that when they purchased a 1932 Twin Six what they had bought was a car fitted with a old motor from the immediate post–World War I era. Accordingly, in 1933 the Twin Six label was dropped and Packard simply called its V12-engined car the ‘Packard 12’; badged this way, it would remain in production until 1939.

The opportunity to view magnificent machines like our featured Packard in a wonderful environment such as that provided by the Warbirds & Wheels display in Wanaka is, indeed, a privilege, and a visit to this facility is highly recommended for anyone, classic-car enthusiast or not.

1932 Packard Sport Phaeton Model 905

- Engine: 67-degree cast-iron V12

- Capacity: 7292cc

- Bore/stroke: 87.12×101.6mm

- Max. power: 119kW at 3200rpm

- Max. torque: 437Nm at 1400rpm

- Compression: 6.0:1

- Fuel system: Downdraught Stromberg EE-3 carburettors

- Transmission: Three-speed synchromesh, freewheeling clutch

- Coachwork: Dietrich

- Front suspension: Solid axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs

- Rear suspension: Live axle

- Steering: Packard worm and sector

- Brakes: Cable-operated Bendix drums, Bragg-Kliesrath vacuum-assisted

- Tyre size: 750×18

Dimensions:

- Overall length: 5500mm

- Width: 1830mm

- Wheelbase: 3620mm

- Front track: 1505mm

- Rear track: 1501mm

- Kerb weight: 2495kg

Performance:

- Max speed: 160kph-plus (Packard desribed the top speed of its new V12 as ‘adequate’)

Did You Know?

- James Ward Packard’s first business venture was as a manufacturer of incandescent lamps based in Ohio.

- The first Packard car was completed on November 6, 1899.

- The Ohio Motor Company was officially established on September 10, 1900 to manufacture Packard cars.

- In the summer of 1903, Tom Fetch and Marius Krarup (the latter being editor of The Automobile magazine) completed an epic 61-day trip from San Francisco to New York in a single-cylinder Packard Model F.

- In that same year Charles Schmidt, driving the Packard ‘Gray Wolf’, set a straight-line mile record of 77.6mph (124.9kph) at Daytona — the record was beaten by Henry Ford’s 999 in January 1904.

- During World War I, Packard had a hand in developing the famous Liberty aero engine, and a special Liberty-engined Packard racing car demolished all existing track records at Sheepshead Bay in 1917.

- Packard was one of the first to fit air conditioning — the ‘Weather Conditioner’ fitted as an option to the Clipper in 1940.

- Packard sold dies to the USSR, resulting in the appearance of Russian Packards — the ZIS — in 1945.

- The Richard Teague–designed Packard Caribbean — introduced in 1952 — looked like a worthy adversary for ’50s style-leader Cadillac, but, alas, the handsome Caribbean never drove as well as it looked.

- In 1954 Packard bought out the Studebaker company, but the additional debts this ailing company introduced led to Packard’s evental demise in 1958.

Missing the January 2014 issue of New Zealand Classic Car (Issue 277) from your collection? Grab a print or digital copy below: