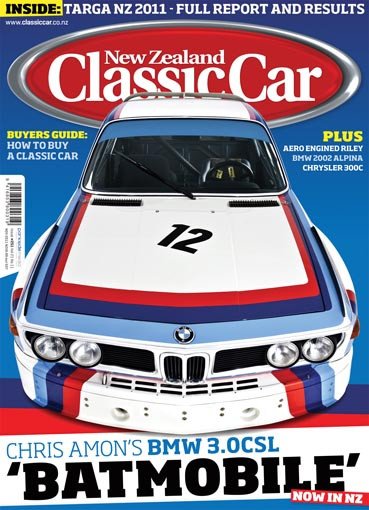

Chris Amon competed in six races during 1973 with the BMW that featured on the cover of the December 2011 cover of New Zealand Classic Car. This was while partnered with Hans Stuck, and they finished in two of those races and won the Nürburgring Six Hour Race. Thirty-eight years later Chris was reunited with the CSL, and we were there to record the occasion.

At the time of the interview, it had been 38 years since Chris Amon raced this BMW 3.0CSL — dubbed the ‘Batmobile’ due to its plethora of aerodynamic aids. Usually resident in BMW’s Museum in Munich, where it is a prized exhibit, this was the first ‘winged’ CSL to win a race. The valuable racing saloon was brought to New Zealand by BMW NZ to take part in 2012’s NZ Festival of Motor Racing (which featured the Bavarian marque), and recently underwent a brief tiki tour to be exhibited at various key BMW dealerships throughout the length and breadth of New Zealand.

On the final leg of its nationwide tour — the return trip to Auckland — the CSL made a slight detour for an appointment with Chris Amon, who last saw the car he shared with Hans-Joachim Stuck during the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) series in 1973.

After examining the car in which he and Stuck had won the 1973 Nürburgring Six Hour that marked the debut of the CSL’s famous wing, we sat down with Chris and prepared to be transported back to a time when drivers such as Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Jochen Mass, and James Hunt all vied for touring car honours. And with the arrival of the 3.0CSL, a mighty battle for supremacy ensued against the rival Capris from Cologne.

From F1 to Touring Cars

Amon was supposed to be racing in F1 for Max Moseley’s March team in 1973 but, in one of Moseley’s typical manoeuvres, he ended up racing a BMW in the European Touring Car Championship. It was an odd position for Amon, whose entire racing career had been largely focused upon open-wheelers.

Chris explained, “It actually came about because of the March connection — in that BMW at that time was supplying engines to the March F2 team and in typical sort of March fashion, they thought that if I drove for BMW, BMW would do most of the paying and they’d have to pay less. As it turned out, I never did actually drive for them, we fell out with them before the first F1 race. But it was through that March connection that it arose. There was another connection there too, because Jochen Neerpasch was managing the BMW team – well, he was managing BMW Motorsport – at that time and he and I had driven at Le Mans together for Carroll Shelby in a Daytona coupé in 1964, so we knew each other well.”

After many years racing in F1 — plus several CanAm drives and, of course, his epic win at Le Mans in 1966 with the Ford GT40 — racing a touring car presented a fresh challenge for Amon; the CSL was far heavier and less powerful than the F1 cars he normally raced. So how did the CSL feel as opposed to an F1 single-seater, and how did he get on acclimatising himself to racing a saloon car?

“Very different!” said Chris with a short laugh. “It certainly did take me a few races to get used to it. I’d done almost zero touring car driving and everything is quite different — with an F1 car you’ve got very little body roll and you haven’t got much suspension movement but with a touring car, it rolls and you’ve got vertical movement. Yeah, totally different. The other thing is that because your cornering speeds are a lot lower there’s a real tendency to try and overdrive because you feel like you’re not going fast enough. And, of course, you’ve got a lot more weight. If you do tend to try and over-drive, actually to over-drive scrubs off speed and [you] go slower so, yes, it took me a while to adapt to it.”

Hans Stuck was much more of a saloon car racing specialist than Amon — but did the Kiwi manage to pick up a few driving tips from the German veteran?

“Not really, I mean he was very quick and it took me a few races to get up to his speed — I got the feeling with Hans that he used to wring the thing’s neck all the time. He was a bit of a larger-than-life character; it was actually a bit special to be driving with him because his father, who was still around at that time — he was quite an old man by then, his father, of course, was part of the Auto Union team before the war. He was Hans Stuck as well, and I got to meet him on several occasions and that took me back to the Caracciola and Nuvolari era. He was one of Auto Union’s probably most successful drivers, Hans’ father. What I did learn from Hans was that you had to go bloody quickly to be on his level.”

Many years after their partnership had ceased, Hans Stuck remembered Amon — “The best driver I ever shared with. I learned a lot from him.”

Amon’s first competitive outing in the 3.0CSL came at Monza where, with Stuck, their CSL finished in fourth place. Amon missed round three at the Salzburgring, Stuck partnering with Dieter Quester for that race. Although they qualified the BMW on pole, a bent valve led to retirement. Amon also missed round three at Sweden’s Mantorp Park, that race took place only a week before Le Mans and BMW intended to enter two works CSLs for the 24-hour race, with Amon and Stuck in car #50. The CSL qualified in 30th position — in a field of 55 cars — but struck gearbox problems during the race when it became stuck in fifth. Although it was eventually fixed, on lap 160 during the night, Stuck hit a Ferrari and ended up in a sand-trap, so their race was over.

Birth of the Batmobile

By this time Amon was becoming comfortable working with the BMW team, which had a reputation as being a pretty slick operation. Chris recalled, “Yeah! I guess, when I went there everybody’s perception of German engineering in motor racing terms, certainly in my case, went back to the Mercedes era of the ’50s, so it was interesting to be linked with a German team. I wasn’t involved with Porsche at any stage so BMW was my first experience. It certainly was slick operation — a very competitive situation, in that basically you had two German teams against each other — you had the BMW team and the Ford Cologne operation, they were the main opposition as such.”

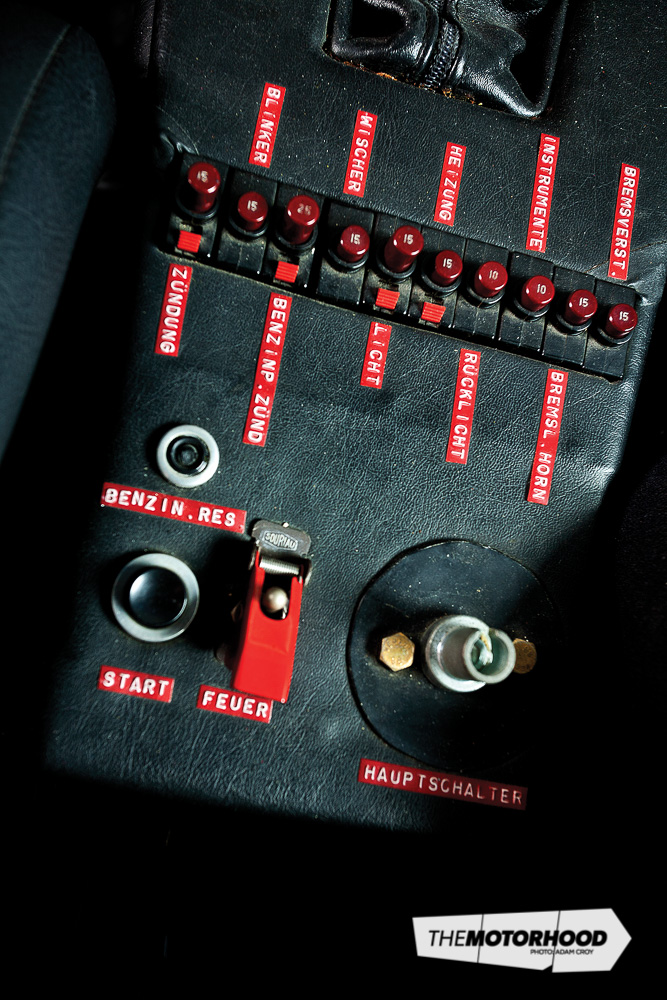

For round four of the ETCC, the drivers faced a demanding six-hour race at the infamous Nürburgring, but the boffins at BMW had a new weapon in their arsenal to combat the all-conquering Cologne Capris – that famous wing.

For the Nürburgring Six Hour race, the CSL appeared for the first time in all its be-winged glory – quickly earning the title of ‘Batmobile.’ Amazingly, the wing slashed lap times at the ’Ring by a whopping 14 seconds.

It took a little prodding to get Chris to remember the wing’s debut race. “To be honest I can’t really remember. When I first saw the car there this morning again after 40-something years or whatever it is, I was trying to think, did we start the season with the wing? I’m pleased you reminded me — that was the first time we ran the wing, was it? Thinking back, somewhere in the back of my mind was the fact that I felt that the wing helped us gain a bit of an upper hand over the Capris. Having said that, at the beginning of the season we were really struggling to be on the same pace as the Capris. When I think about it, there were two things that happened during the season that helped us get ahead of them — one was the wing and the second was when we went from a 3.3- to a 3.5-litre engine. I can’t remember what race we got the bigger engine.”

During the actual race, the Amon/Stuck CSL finished first with an average race speed of 158.5kph and, in the process, put an end to the Capri’s winning ways.

The victory at the ’Ring was Amon’s first race win since the Argentine GP in 1971, so it felt good to be back on the winner’s podium.

“I think by the time we got to the Nürburgring I was really starting to enjoy the touring car thing, and whatever you’re driving at the ’Ring it’s always a challenge and it’s always satisfying to do well there. So, yes, it was a big moment.”

On song

By the time the BMW works team arrived at Spa for the 24 hour race there in July, Amon had become very comfortable at the wheel of the CSL and his driving skills were plainly evident – during the Spa race, he recorded the fastest lap with a time of three minutes, 49.4 seconds at an average speed of 221.586kph. To put that into perspective, at the old Spa circuit Chris set the fastest time ever in the 1970 March at three minutes, 27.4 seconds.

Stuck had put the CSL on to pole with a time of three minutes, 49.9 seconds, then during practice, Amon punted an Alfa at high speed causing last-minute repairs before the race but they were forced to retire after dropping a valve on lap 90. Alpina withdrew its cars following a multiple car pile-up in which one of its drivers, Hans-Peter Joisten, was killed. The Quester/Hezemans works CSL won.

Although Amon couldn’t recall when the 3.5-litre engine was first fitted to the CSL, the history books show that it made its first appearance at round six at Zandvoort. However, the larger engine didn’t immediately give the BMWs an advantage, and excessive tyre wear led to the team cutting holes in the spoilers to aid tyre cooling. The Stuck/ Amon pairing started from pole, but despite a spectacular driving stint from Amon, the CSL’s gearbox gave way, leaving the Hezemans/Quester BMW to take the race win.

Amon’s last drive in the CSL came at Paul Ricard – he missed the final round of the series (the Tourist Trophy at Silverstone) because he was racing an Elf-Tyrell at Watkins Glen where, once again, Stuck qualified the CSL on pole. Losing gears again, Amon and Stuck finished in third place. Although stuck in fifth gear they managed to circulate within 10 seconds of their normal lap time. Hezemans and Quester took their third straight win, Toine Hezemans gaining the 1973 driver title and BMW the 1973 European Touring Car Championship.

Grinding the equipment

With his single season in the BMW CSL behind him, Chris remembered that both he and Stuck had been pretty hard on the car — for Stuck, it just appeared to be his driving style, while Amon drove equally as hard in order to match his partner’s pace.

As Chris recalled, “Actually, just on that, we didn’t have a great finishing record that year. The other team car was driven by Dieter Quester, the Austrian, and Toine Hezemans, the Dutchman – they were better at finishing races than we were, but we were driving a bit harder, grinding the equipment down a bit.”

Amon now returned to his more usual F1 stamping ground — but did he consider staying on at BMW for another season?

“I would’ve very much liked to have stayed with the BMW team but my focus as the season went on was to build my own F1 car, and I wanted to be fully committed to that. In hindsight, it was a bloody disaster, but we won’t go into that. So, I never really considered trying to stay with BMW because I really wanted to focus on the F1 issue.”

As far as BMW is concerned, the Amon/Stuck CSL is a prized possession — reputedly worth around $1.5 million — due to the simple fact it was the first winged CSL to win a race. For Kiwi motorsport fans it’s all about the car’s connection to one of New Zealand’s best ever racing drivers.

Chris Amon’s BMW 3.0CSL race record

Part of a two-car works team, the pairing of Chris Amon/ Hans Stuck and Dieter Quester/ Toine Hezemans competed in the eight-round 1973 European Touring Car Championship in the BMW 3.0CSL.

Round one

March 25, 1973 — Monza 4

Hour race

The Dieter Glemser / Jackie Stewart Capri took the round win, while the Chris Amon / Hans Stuck BMW finished in fourth place following engine valve problems.

Round two

April 22, 1973 — Salzburgring, Austria

Only one works CSL was entered for Stuck/Quester — they qualified on pole, but retired with a bent valve on lap 41. The Glemser/Fitzpatrick Capri won the race.

Round three

June 3, 1973 — Mantorp Park 500km, Sweden — 500km

Only one works CSL was entered for Hezemans/Muir, they finished second behind a Capri.

Le Mans 24 Hour

June 9–10 1973

Two works CSLs were entered, for Amon/Stuck and Quester/Hezemans. The Quester/Henzemans CSL finished 11th overall, while Amon/Stuck were classified in 33rd place.

Round four

July 8, 1973 — Nürburgring Six Hours, Germany

Debut of the winged 3.3-litre CSL. Amon/Stuck finished first.

Round five

July 21–22, 1973 — Spa 24 Hour, Belgium

Amon/Stuck retired after dropping a valve on lap 90. Alpina withdrew its cars following a multiple car pile-up in which one of its drivers, Hans-Peter Joisten, was killed. The Quester/Hezemans works CSL won.

Round six

August 12, 1973 — Zandvoort 4 Hours, Holland

Debut of the 3.5-litre engine. Stuck/Amon started from pole but the CSL’s gearbox gave way, leaving the Hezemans/Quester BMW to take the race win.

Round seven

September 2, 1973 — Paul Ricard Six Hours, France

Stuck took pole again with a time of two minutes, 8.4 seconds, but the car finished in third due to gearbox problems.

Round eight

September 23, 1973 — Tourist Trophy, Silverstone, UK

Minus Amon, Stuck put his CSL on pole yet again but suffered a broken clutch in race one so did not start the second race. Stuck and Amon finished the 1973 championship with 32 points, in equal-seventh with Niki Lauda.

This feature was originally published in the December 2011 issue of New Zealand Classic Car (Issue No. 252). You can collect a print copy or a digital copy below: