At the end of a long day, we were negotiating a narrow, winding country road in the pitch-black of early evening, unsure of where or when the next turning might be. This was, we were told, the most remote part of Austria, somewhere between Salzburg and Vienna but well off the beaten track, and we were headed for the Hotel Schloss Pichlarn at Irdning. Hardly the best situation for evaluating a red M3 BMW E30, and we were discovering what this car liked least of all — quiet, pottering motoring.

M3s have always been less about the mundane things in life and more about speed and action — three decades ago, the debut model made this all so apparent. If performance was your forte, the M3 was the prize in the BMW E30 range. Even though the E30 remains the smallest and least powerful of any BMW M Series model, and the only one with a four-cylinder engine, the inaugural M3 has taken on iconic proportions, in part due to its remarkable competition heritage. Less than one per cent of all E30s made between 1982 and 1991 were M3s, in stark contrast to the importance of this homologation special.

BMW had to make at least 5000 examples to qualify for motor sport but actually built 17,970 E30 M3s, including the rare convertible models, compared with the total E30 production of 2,339,520. The fact that all were left-hand drive allowed little opportunity for many to find their way to markets like the UK, Australia, or New Zealand, although South Africa produced its own four-door M3 version in limited numbers. The M3 production tally comprised 16,584 so-called standard models, 1154 Evolutions, and Johnny Cecotto and Roberto Ravaglia Editions. Sport Evolution versions were only painted in red or black.

The good news had spread by the time BMW built subsequent M3 models. M3 versions of the E36, which launched in 1992, amounted to 63,070, while 85,744 E46 M3s (1999–2006) in total were sold. Clearly, E30 M3s would always be thin on the ground, but New Zealand is believed to be home to 20 road- and race-car examples. E30 M3s out of Japan currently fetch up to NZ$50K, good examples from Europe range between $70K and $90K, and racing versions with solid competition histories have been valued as high as $200K.

Brilliant competition record

With its simple front engine, rear-wheel-drive layout, carefully honed mechanicals, distinctive two-door body, and brilliant competition record, the E30 has long been regarded as the most iconic M-car of all time.

The M3’s 2.3-litre S14 engine, originally adapted for Formula 2 and essentially a six-cylinder M1 power plant with one bank of cylinders cut off, was developed by a team led by Paul Rosche. In creating the twin-cam, 16-valve, cast-iron-block Bavarian jewel, the team initially saw the engine producing 143kW or 158kW without a catalytic converter. Topped with an alloy cylinder head, the M3 power unit was fitted with electronic ignition and Bosch Motronic ML fuel injection.

The car’s suspension closely followed that employed by less powerful E30s, with MacPherson struts up front and rear trailing arms. However, the M3’s set-up was lower, firmer, and with revised front-wheel geometry. Three Evolution versions followed the first M3s built from 1986, with varying levels of power. The final rendition achieved 195kW, a top speed of just on 250kph, and a 0–96.5kph (60mph) time of 6.1 seconds. While the early versions had an engine displacement of 2302cc, the Sport Evolution’s motor was 2467cc.

The M3 boasted larger discs and wider wheel arches to accommodate up to 10-inch-wide rims. Visually, the car was distinguished by a deep front spoiler and a flatter rake to the rear screen, while boot-lid height was raised 40mm — all to improve downforce. A standard E30 has a drag factor of 0.38, while the M3’s is 0.33. Weight savings included thinner glass for the side and rear windows and a plastic boot lid and bumper. Later cars had suede on the steering wheel and gear lever.

A different beast

On that quiet Austrian drive over back-country roads, the impressive engine output figures and suspension and body refinements didn’t count for much, because the nature of the route dictated a relatively modest pace and the M3’s engine proved a lacklustre performer at low revs. At around 2500rpm, you were wondering what all the fuss was about, yet, once the tacho surged past 4000, the BMW became a different beast.

A second stage of the power delivery spiked at 5500rpm, racing through to a wonderful-sounding 7250rpm limit. The five-speed Getrag gearbox, with dog-leg first, was precise enough but needed plenty of work on the tight rural roads, with the motor’s peak torque developed at reasonably high revs. This was never going to be an ordinary motor, even if it was hardly the smoothest of BMW power units.

Free-revving performance

The E30 M3 project team was led by Thomas Ammerschläger, a former Ford Capri and Audi Quattro chassis engineer who favoured a large cylinder bore. Rosche said the power unit worked well right from the start, and the very first M3 engine was built entirely by hand. It spun easily up to 8500rpm, and the engineers reasoned it would have been even better with a turbocharger; however, BMW management deemed this too costly given the remaining life of the E30 model cycle.

The late Paul Frère, the highly respected motoring journalist who won Le Mans in 1960 for Ferrari, described the first M3 as “a dream of free-revving performance”. After attending the Italian launch in 1986 he added, “This M3 reminded me of a BMW 2002 Alpina with 160 horsepower [119kW], of which I had been the proud owner in the early ’70s, except that the M3 had a much higher top speed, far better road-holding and also much better brakes.”

The M3 did much to raise the image and mana of the E30, and it soon became evident that the 3 Series would be the mainstay of BMW sales in New Zealand and, of course, other markets.

In the ’70s, it was the 1600/2002 series that marked a turning point for the marque, followed by the first-generation 3 Series 40 years ago, and, although clearly a progression of the E21, in many ways, the E30 successor marked a coming of age for BMW, with its good-looking body, styled by Claus Luthe, who had also been responsible for the NSU Ro80.

Since then, the following four generations of 3 Series have accounted for at least 30 per cent of BMW’s worldwide sales, and the car has been a long-time favourite in our market. Local sales figures prior to 1995 are vague, but, since then, the E46 series has been most popular, with the golden years being 2002 (with 915 New Zealand–new registrations) and 2003 (910). Internationally, the car’s biggest production year was also 2002, when 561,249 examples were built.

The third-highest local sales year was captured by the E36 generation in 1995 (730), and, in 2001, the E46 managed 695 sales. By 2013, 3 Series demand was still high, with 588 buyers, with the next best years being 2004 (583), 2014 (572), 2000 (562), and 1999 (538).

The New Zealand population of 3 Series BMWs has been hugely inflated by used-import examples, not only from the UK but also from Japan. As the 3 Series celebrates its 40th anniversary and 13 million global sales, it will be remembered for the spirited in-line six-cylinder models and efficient diesel versions that are both quick and highly economical.

Turning point

Seven years before my Austrian adventure, I had been one of 31 Australian and New Zealand journalists on a five-day E30 3 Series drive programme covering 1300 wintry kilometres from Christchurch across the Southern Alps, down the West Coast through the Haast Pass, and on to Queenstown before the run back to Canterbury. It was the most expensive press launch for any new-model car in New Zealand, but, more importantly, it marked the expansion of BMW in our country in 1983. For the first time, a built-up-vehicle franchise was represented by the manufacturer rather than an agent, signifying the second-generation E30 series as something of a turning point in the German car-maker’s local history.

At the Christchurch dinner before day one, Ross Jensen — who was being presented with a new 3 Series sedan as part of the handover of the New Zealand BMW distributorship to the parent company — worried to me about the driving calibre of some of the motoring journalists. It was as if he had a premonition of what was about to occur.

Less than 24 hours later, following a coffee stop at Arthur’s Pass, we headed down towards Greymouth on a cold and grey afternoon, fearful of black ice in shaded spots. We rounded a corner to find that, indeed, unseen ice had claimed a victim, with one of the 13 E30 3 Series press cars off the road and upside down straddling the main railway line to the West Coast. The two occupants clambered out unscathed as other BMWs arrived, including that containing Ron Meatchem, managing director of BMW Australia, who looked at me with a somewhat pained expression and said, “It would have to be Jensen’s own car!”

In 1983, the E30 was pivotal to BMW making serious inroads into New Zealand’s luxury car market, beginning with the two-door six-cylinder 320i that retailed for $32K and the 323i at $43K, while the four-cylinder 318i followed a year later at $34,500. By that time, the larger-engined versions had risen in price, while the 323i was replaced by the 325i in 1986. When the last of the E30s arrived, in early 1991, a four-door 325i SE cost a hefty $79,800 with manual transmission and $84,900 with an automatic one.

Hot property

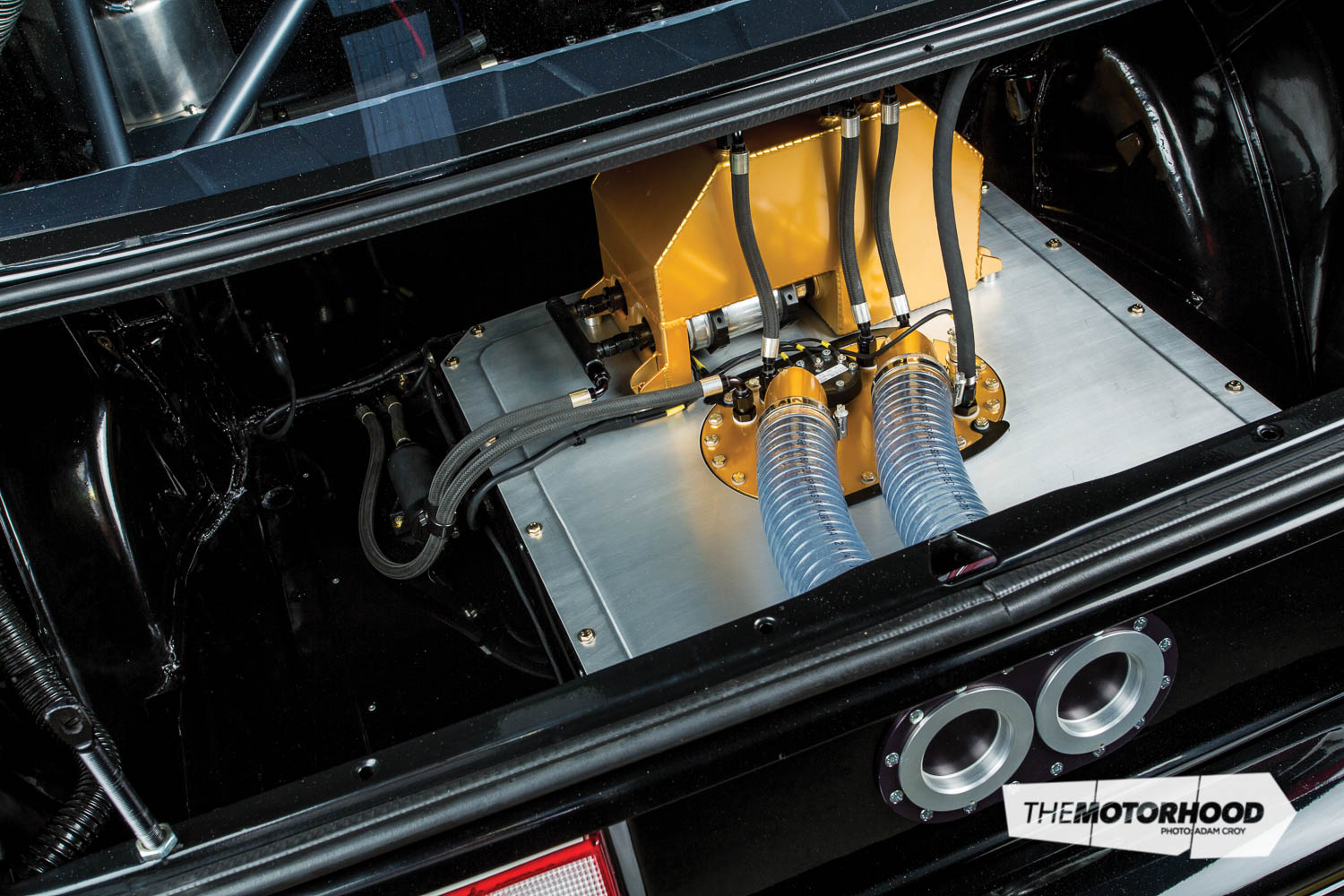

A racing class for the model was created 14 years after the last new E30s arrived here, allowing 1.8-litre and 2.0-litre versions plus an open category for classic M3 versions. The E30 spawned the largest one-make class in New Zealand, with ageing, used 3 Series sedans hot property as potential race cars. M3s have long been prominent on New Zealand race tracks, and the E30 series won no fewer than 12 major touring-car championships globally between 1987 and 1991. The car has inspired Conrad Timms of M3 Motorsport Ltd to design and make selected parts for the model in New Zealand.

The list of drivers who raced E30 M3 sedans reads like a who’s who of down-under motor sport, with names such as Peter Brock, Jim Richards, Paul Radisich, Trevor Crowe, Mark Thatcher, Robbie Francevic, Brett Riley, Tony Longhurst, Allan Grice, and Graham Lorimer. Sadly, Denny Hulme suffered a fatal heart attack while racing the Benson & Hedges–liveried yellow-and-white M3 at Bathurst in October 1992.

Memorable M3 moments

My time with E30s included an absorbing day at a test facility in Queensland with Australian racing driver Frank Gardner, who

This article originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of New Zealand Classic Car (Issue No. 302). Grab your print or digital copy of the mag now: