The XJ220 has a complicated past, but it’s still one of the few cars that will impress every person who sees it in the flesh, car fan or not. We spent some time with Jaguar’s game changer and discovered there’s more to the Jaguar than sordid tales of lust and anger

Like other supercars of the time, the XJ220 was a skunkworks project. It was undertaken by a ragtag team of Jaguar engineers who called themselves the ‘Saturday club’. They would spend their nights and weekends on a mission — essentially, to save the ailing brand from the scrapheap following a decade or two of production-car failures and mediocrity — and all for no pay or a guarantee their project car would see the light of day. Fresh out from under the thumb of British Leyland (which was effectively a government department, and was being run as such), the team at Jaguar knew it had an opportunity to rebuild a quintessential British brand from the ground up. No small task.

Where there had been recent success for Jaguar was on the race track. Following a successful partnership with Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) — which had raced the XJS from 1982 to 1986 and topped the podium in the 1984 European Touring Car Championship — Jaguar’s head of engineering approached TWR, which was entrusted with coming up with a an engine capable of powering a marquee car for the brand, something that could be sold to road users, compete against the Ferrari F40 and Porsche 959, and also eventually be used at Le Mans.

And so, in an age of excess and flamboyance, the conclusion seemed forgone: spend millions on wind-tunnel development to make aerodynamic advances so ahead of their time that some are still in use on supercars today and deliver power via a highly tuned V12 engine with dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder, with a 373kW output and decades of proven motor racing provenance, including use in Tom Walkinshaw’s fabled XJR-9. And all this as well as an advanced four-wheel-drive system attached to a sleek aluminium body big enough to be spotted from the moon.

Bubble brewing

Following the launch at the 1988 British Motor Show, Jaguar began taking deposits for the XJ220 from a new era of Jaguar fans, who urged the manufacturer to build the car. With a flurry of excitement, the concept was to become reality, and over 1000 prospective purchasers, who appreciated that the XJ220 had the potential to be one of the greatest cars of all time, put down the £50K deposit almost there and then. Word has it that that year’s show saw a bump of 90,000 visitors, all there to see the XJ. Even the neighbouring stall-holder’s Ferrari F40 and its associated scantily clad women couldn’t tempt the crowds. Yet, at £400K — which was more than twice the price of the Ferrari, making it the most expensive car in the world at the time — sales proved more impressive than Jaguar had anticipated. With hindsight, the appeal of such a questionable investment strategy was unsurprising, given the time.

Not long after those deposits were banked, there was an announcement from Jaguar. The big 12-pot engine, Lamborghini-style scissor doors, and four-wheel drive had gone. Instead, customers were told that their new supercar would be delivered with a twin-turbocharged V6, rear-wheel drive, and doors that opened outwards. Disappointment ensued, lawyers were engaged, and threats were made.

Six of the best

So, why did Jaguar suddenly turn its back on a V12 with such pedigree and instead opt for such an unfamiliar and seemingly untested power plant?

While tyre manufacturer Bridgestone was happy to create rubber specifically for the XJ220, it wasn’t confident that it could produce a tyre capable of holding the Jag’s promised aerodynamically enhanced downforce of 1360kg, or cope with its mooted top speed of 220mph (354kph). There were also rumblings about emissions issues. While emissions are at the top of mind for (most) vehicle manufacturers these days, the 1980s were a different time. But a car powered by a decades-old 7.0-litre V12 production engine seemed a step too far for regulators, even then. On top of all this, Tom Walkinshaw was looking closely at the F40 and 959, which were lighter, smaller, and just as powerful as the V12 Jaguar. It seemed that the Jag might be old hat before it was released.

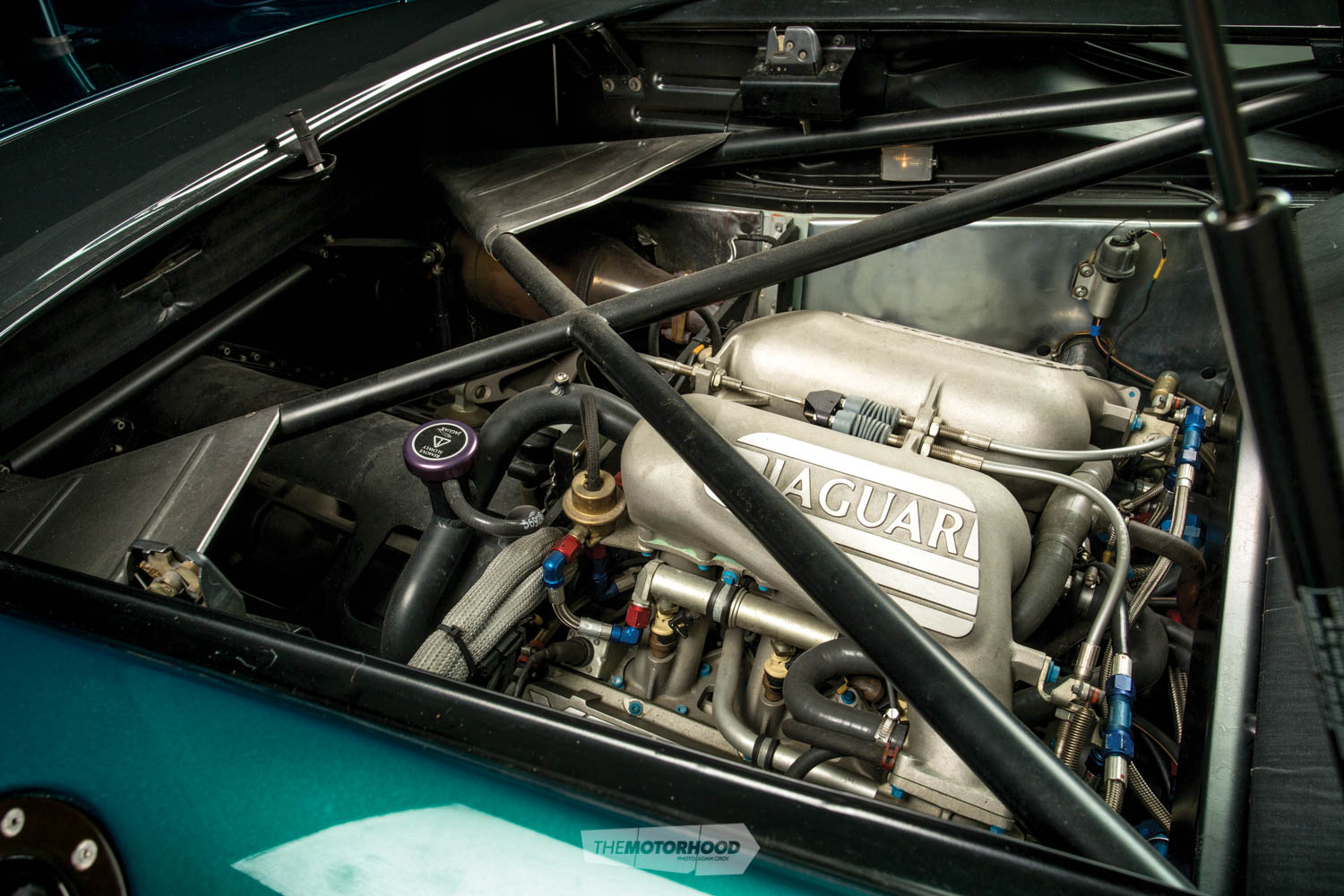

With all this information at hand, TWR began looking at other options to power the XJ220. As it happened, it owned the rights to another engine with significant racing prowess, although that one came with half the cylinders. It was a power plant worked over by former Cosworth and Williams Formula 1 engineer Dave Wood for the Metro 6R4 rally cars. Once again, the engine was fettled, this time for Jaguar’s use, and it ended up as a 3.5-litre twin-turbo V6 putting out 404kW for the road-going version.

Ready to drive

Thus, with the new engine and configuration in place, it was time to get the manufacturing process underway. However, in the summer of 1989, as the economy began to tank on the back of questionable investment strategies, buyers became willing to forego their deposits rather than go through with the purchase of the XJ220. Jaguar had other ideas — after all, it had made a massive investment on the back of a healthy order book, and it successfully pursued several buyers in court to force them to continue with their purchase. But, in the end, Jaguar was forced to refund a number of deposits to relieved buyers as production numbers were significantly scaled back.

Once the production car made it to the road, those who had retained their place in the queue — whether for fear of legal action or a genuine desire to own a piece of Jaguar history — can’t have been too disappointed. With the race-tuned V6 in place, the lighter block and lack of four-wheel-drive componentry meant the car could go around corners pretty damned well. So well, in fact, that the XJ220 became the fastest production car in history, demolishing the Nürburgring road-car record in the process.

Long road to stardom

Despite being built in such limited numbers (initially production was 350 units, which was scaled back to 281 as the economy hit the skids and demand dropped away), XJ220 values slumped considerably following its release. It is rumoured that at one stage there were several available in the UK for under £40K, with one canny buyer spotting an opportunity to pick up two of them at that price. Whether it was the bad taste Jaguar had left in the mouth of scorned collectors; the general state of the automotive investment market; or the fact that Bridgestone’s bespoke tyres were no longer manufactured, so no tyres were available, values stayed down for a long time. It wasn’t until 2014 — when Bridgestone announced it would team up with Don Law Racing (DLR) to manufacture a new bespoke tyre for the XJ220 — that collectors once again saw the benefit of owning a car built in such limited numbers and with such a fabulous story behind it. Values have now soared, and good, low-mileage examples (such as our feature car) now fetch well into seven figures.

So, how will this iconic cat go down in history? The story has it all really — dreams, hype, failure, and redemption, and so it seems any lingering bad taste left by the maelstrom of the early days has disappeared, and we can now count the XJ220 as living in the rarefied atmosphere of ‘best ever’.

1994 Jaguar XJ220

Engine: Jaguar/TRW V6

Capacity: 3498cc

Bore/stroke: 94mm/84mm

Valves: Four valves per cylinder, DOHC

Comp. Ratio: 8.3:1

Max power: 404kW at 7000rpm

Max torque: 641Nm at 4500rpm

Fuel system: Fuel injection / Twin Garrett T3 turbochargers

Transmission: Five-speed manual

Suspension F/R: Double-wishbone, push rod and rocker–operated dampers, anti-roll bar / Double-wishbone, toe-control links, twin rocker-operated damper units, anti-roll bar

Steering: Rack-and-pinion, power-assisted

Brakes F/R: Ventilated disc

Dimensions

Overall length: 4928mm

Width: 2010mm

Height: 1149mm

Wheelbase: 2642mm

Track F/R: 1650mm/1650mm

Kerb weight: 1470kg

Performance

Max speed: 340kph

0–60mph (95.6kph): 4 seconds

Standing quarter-mile: 11.6 seconds

This article originally appeared in NZ Classic Car Issue No. 317 — Click the cover below to purchase a print copy of the magazine