For American brothers Don and Bill Whittington, the ’70s and ’80s were whirlwind of drugs, duffel bags full of cash, fast cars, glorious moustaches, and a bunch of other illegal stuff

The 1979 24 Hours of Le Mans marked two key events in history — Kremer Racing became the biggest name in endurance racing that year, and two relatively inexperienced and unknown American drivers were slingshotted to the forefront of the racing world.

How they were able to get behind the wheel at the biggest endurance race of the year is a story that most have never heard, and one that would make a lot more sense as you begin to dig into the rise and fall of Whittington Bros Racing.

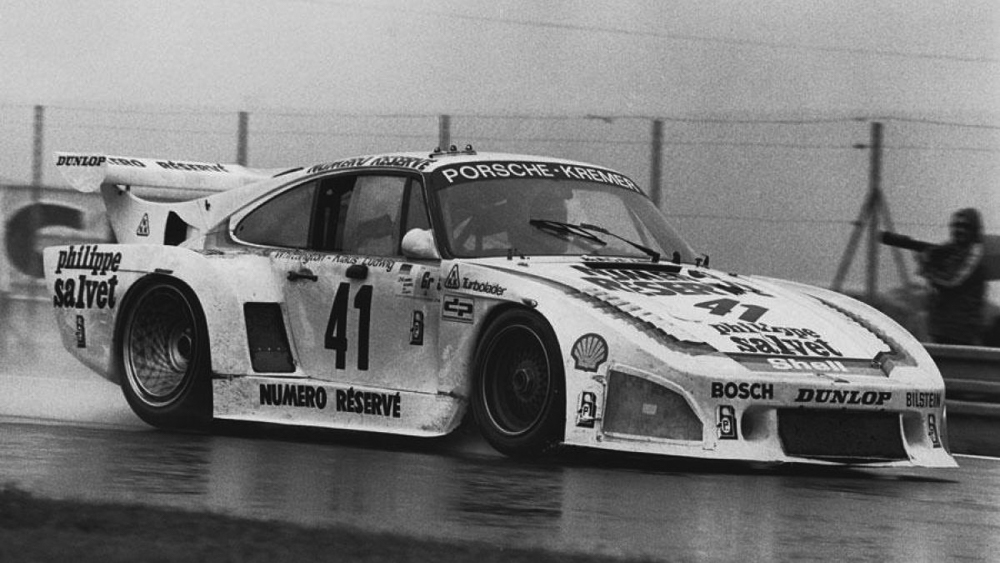

Don and Bill Whittington arrived in France after forking out $20,000 in cash each for a drive in the Kremer Racing Porsche 935 K3 alongside Klaus Ludwig in 1979. Formed out of a funding deal between the brothers and founder Erwin Kremer, things would nearly turn sour after Kremer told the pair that they would drive after Klaus had put in the leg work.

Not satisfied with that order after handing over a very decent chunk of cash for the time, the brothers protested the decision and asked Kremer what they would need to do in order to drive first.

Kremer light-heartedly joked: “You can buy the car … for $200,000.”

Now, it’s important to note, that Kremer was already offering the car for sale at the time for far less and the price was an obvious inflation in order to shut the brothers up. So it was to his shock when they responded in agreeance, telling Kremer to “go into the trailer and collect $200,00 and not a penny more from the duffel bag.”

True to their word, there was the right amount of cash awaiting Kremer and both Don and Bill were given the first drives. Reality would dictate that regardless of this fanfare it was actually Klaus that put in the hard yards to pull through for the win, however, the Whittingtons were instant Le Mans winners and the Kremer 935 K3 orders were going through the roof — the brothers supposedly offering up the rest of the duffel bags contents as payment for a few more cars.

The pair returned home to purchase the Road-Atlanta road racing circuit before diversifying into IndyCar and NASCAR racing. Both brothers raced in five Indianapolis 500’s, with a Don managing best finish of sixth, with Bill in 14th. Don made 10 NASCAR starts, while Bill only made two, with both finishing with lack-luster results.

In 1984, the brothers linked up with mildly-successful driver Randy Lanier to form Blue Thunder Racing — an IMSA team that appeared seemingly out of thin air in the eyes of their competition. Blue Thunder won race after race at places like Watkins Glen, Laguna Seca and more, and earned enough points to be the IMSA champions for the same year, earning the top sports car racing title in the country.

How they managed to fund these exploits, however, became an increasing interested amongst fellow racers and eventually the IRS, alongside the DEA. We mean, they were clearly rich, but no one knew where all the money was coming from and at the rate they were spending it, there was a lot coming in.

Even lesser known was that the Whittingtons had purchased a for-hire plane company and according to ex-Canepa historian John Ficarra, two planes would be flown in the dead of night in unison where the back straight of Road-Atlanta was utilized as a runway while the other landed at a regular airport to cover their tracks. What they were hauling? Pot, lots and lots of pot. Ficarra alledges that there were areas of the circuit that weren’t permitted for anything to venture into and stored huge amounts of marijuana — explaining where all this cash flow came from.

The Whittingtons clearly live outside of the rules, and that attitude transferred into their racing where cars were run without any sponsors at all, or those that were found on the cars, completely fake — notable was C.W. Cobb, a suntan lotion distributor that would later be found to be a shell company for a $300 million pot smuggling ring. They would even go as far to hire models to spray perfume on fans claiming it to be one of their sponsors new products, for a company that didn’t exist, and using relabelled from genuine brands.

C.W. Cobb, a Fort Lauderdale suntan lotion distributor who was later convicted of running a $300 million pot smuggling ring uncovered during a federal probe dubbed “Operation Sunburn.”They were known to bend the rules, too, after a restoration team taking car of the Le Mans-winning Kremer 935 K3 found a large empty cavity in the driver’s side sill. Consulting with mechanics and crew members that worked on the car after it had moved to the U.S., it was revealed that a nitrous oxide kit had been added to bump the already 750hp package upwards of 1000hp, an act that would regularly see the car roll across the finish line completely destroyed after the $40,000 engine had let go — there were most certainly there for a good time, not a long time.

It would catch up with the brothers eventually, when in 1986 both brothers would plead guilty to charges of income tax evasion, money laundering, and conspiracy to smuggle cocaine from Columbia. The men pleaded guilty and agreed to forfeit $7 million worth of propery — including the Kremer Porsche 935 K3, which now lives at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Foundation meuseum — and Don Whittington received an 18-month prison sentence, while Bill was hit with 15 year. Fellow IMSA drivers Randy Lanier, John Paul Sr., and John Paul Jr. would also see prison time for their involvement in the operation.

Both are out of jail and currently run aircraft company, World Jet, which has been under investigation for multiple drug trafficking-related crimes — their driving careers seemingly ended with their convictions.

From Le Mans-winners to ex-cons, the Whittington brother’s story is one that needs to be turned into a movie …