Renault’s swoopy Fuego was much more than a styling exercise, as Donn Anderson recalls. But where are they all today?

As market values for classic cars rise, so does the popularity of unloved classics. But there is more to it than that, since some less-popular old cars are actually unique and worthy of both preservation and cosseted ownership.

A recent analysis of 30 million cars in Britain highlighted the plight of many older cars that are verging on extinction. The survey revealed that only one example of a staggering 222 models from the past 50 years is still in use. British Leyland built two million Metros, but there are now fewer than 3000 of them registered for use on the roads today, and a mere 183 Austin Maestros from a total production of 325,000. Contrast this with MGB production of just over half a million, of which 19,000 are still in regular use. The highest surviving percentage rate was the Lotus Elan, with more than 1700 early examples, while the Triumph Stag was runner-up, with 3542 in use from a production total of 26,000. Just 161 Austin Allegros from 640,000 are still licenced, with more off road in collections! More than 800,000 Morris Marinas were made between 1971 and 1980, and now only 22 are licenced. Clearly, the British have a better love affair with the Morris Minor, which boasts a current running total of 14,294. Just 68 Alfasuds are still in use, while a mere 22 Datsun 120Ys are running, honouring the rest that have rusted away. Finally, unsurprisingly, 748 Ferrari GTBs from 1975 to 1985 are registered — almost all of those sold new in the UK.

You need to look far and wide these days to find a Renault Fuego, with only 19 currently registered in Britain and probably many fewer than that in New Zealand, where the model was imported from 1981 until 1986. However, just how accurate these survival figures are is questionable, because of those tucked away off road and de-registered. Jeremy Clarkson indicated in 2011 how few Fuego Turbos were still in use in Britain (just five now), while, two years ago, the Honest John website quoted 75 as the number of all Fuego models registered in the UK.

Subjected to verbal abuse perhaps more frequently than most, the stylish French coupé was often described as the car of choice for Parisian prostitutes, while others opined that it was shaped like a walrus with gas. Yet the car had several other more substantial claims to fame. The late John Wood, general manager of Eurotrans Motors, the New Zealand concessionaire for the French marque at the time, believed that the arrival of the Fuego (pronounced ‘foo-ay-go’) on our market would be an image-booster and bring new clients to Renault.

He was right. As the first examples arrived, there were waiting lists for the Fuego, with some dealers reckoning that the newcomer would kill the sky-high Mazda RX-7 market. That didn’t quite happen; although, from a situation in 1980, when Eurotrans held big stocks of unsold new Renaults, the brand moved to late 1981 with no inventory of product and forward shipments already sold. Renault was the best-selling built-up car brand in New Zealand in 1983, outgunning BMW, buoyed by the 1.6 GTS and 2.0 GTX Fuego that was the most popular fully imported coupé. It was also the best-selling coupé in Europe from 1980 to 1982, in a moment of glory scarcely remembered today.

A US advertisement for the Fuego Turbo reflecting the Formula 1 heritage. Note the different headlights and alloy wheels

Styling and aerodynamics

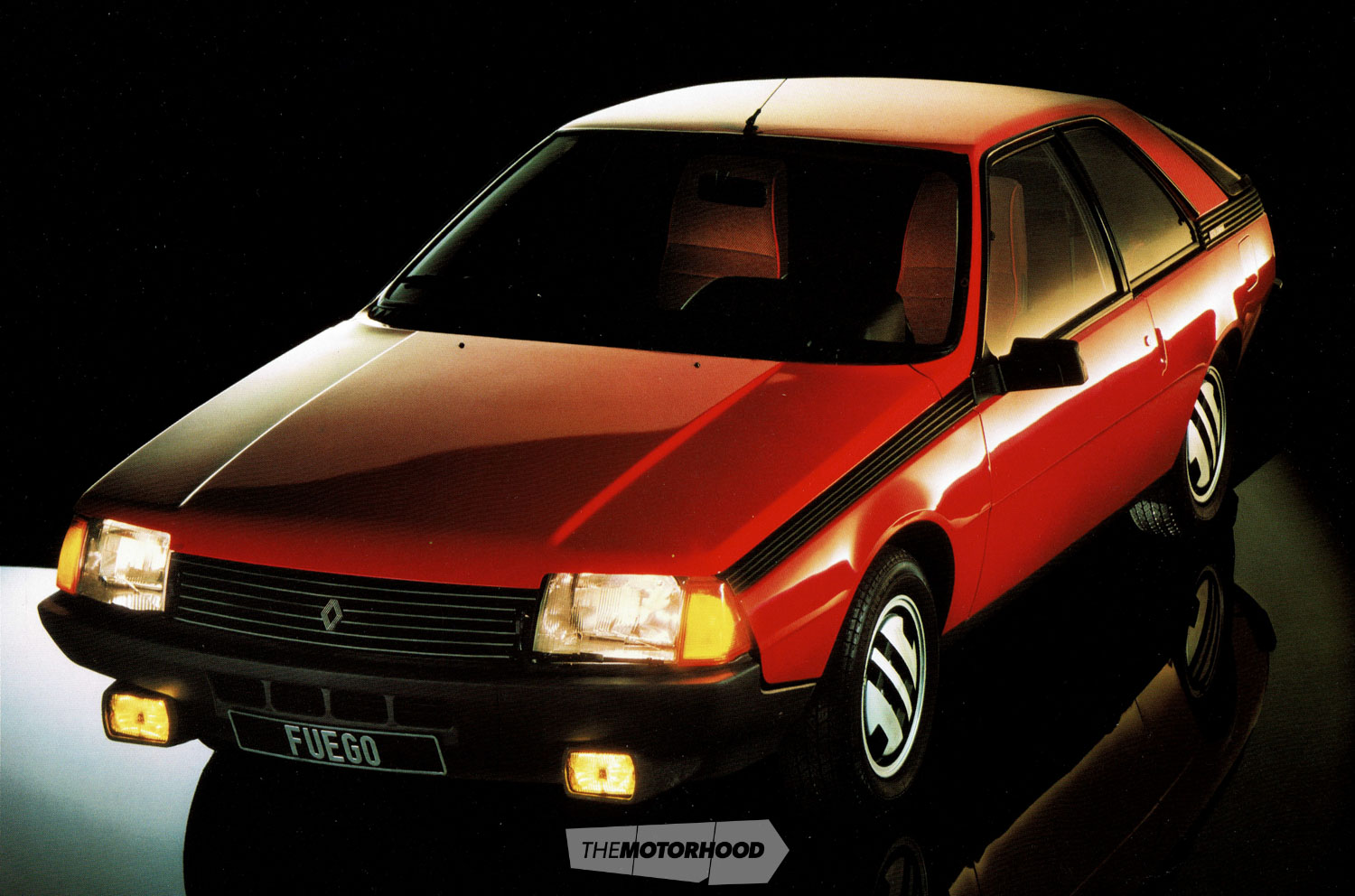

However, there are other more compelling reasons why we should remember the Fuego. From 1983, it was the first car to have the now-near-universal remote keyless locking — referred to as ‘PLIP’ and named after Frenchman Paul Lipschutz — and broke new ground with steering-wheel-mounted controls for the audio. The Fuego was claimed to be the first mass-produced car designed in a wind tunnel, which lead to the excellent cd (drag coefficient) of 0.34. It was described as an arresting combination of styling and aerodynamics. Look in vain, for example, to see external door releases, because they are hidden within body indentations by the B-pillar.

This car is nothing if not distinctive, encircled by a thick black plastic belt line and really looking like nothing else. The late motoring writer LJK Setright declared, “It is blessed with a body which is not only roomy and aerodynamically efficient, but is also beautiful.” Renault preferred to call the car a “two door, four seater” rather than a coupé.

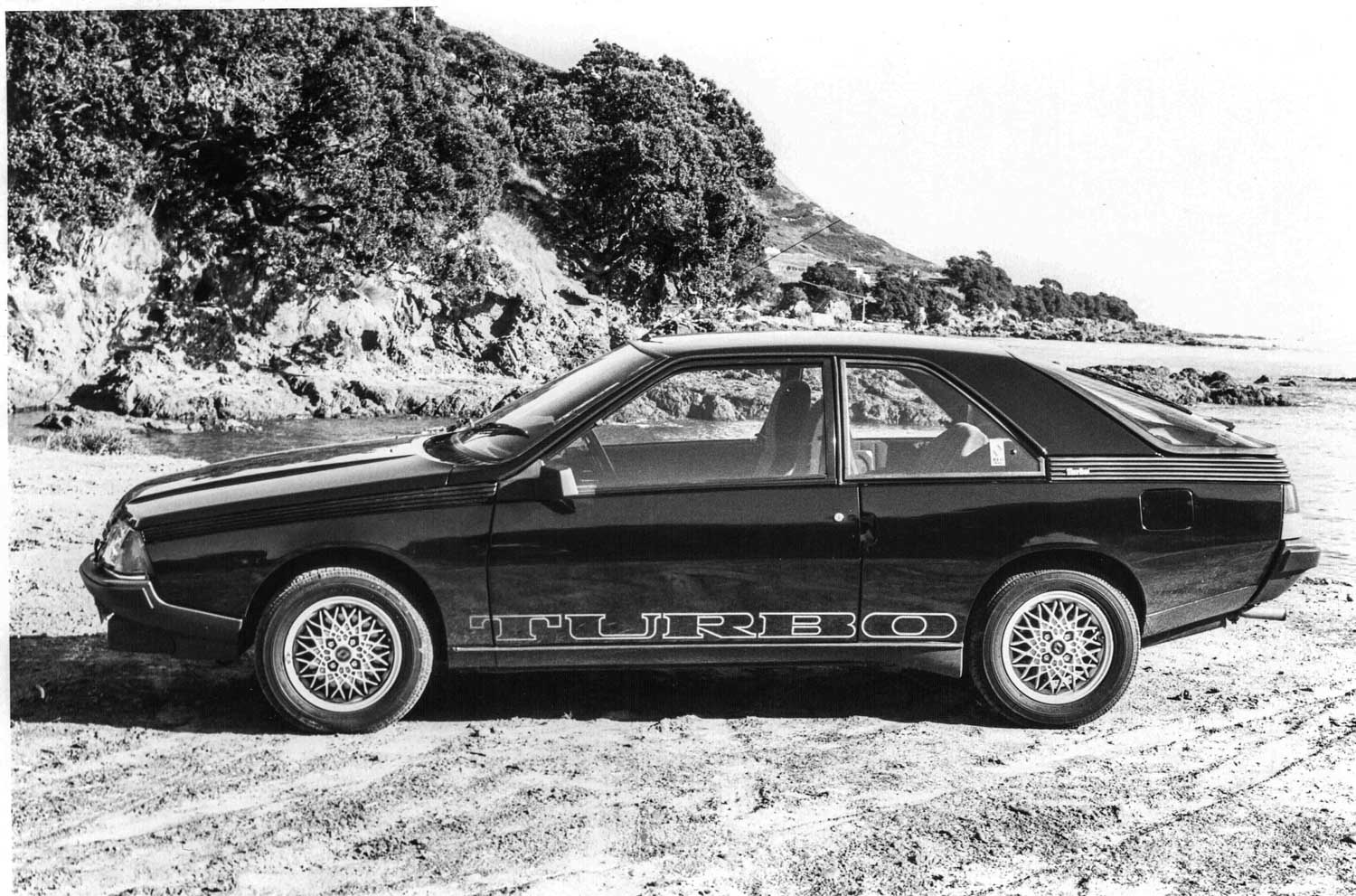

With a top speed of 180kph, the rare turbo-diesel version, which was not imported here, was, in its day, the fastest diesel car in the world. When the turbo-petrol engine became available late in 1983, the brand aligned the Fuego with Renault’s spectacular involvement in Formula 1. Outwardly, this most powerful of Fuegos was distinguished by huge ‘Turbo’ logos along the smooth body flanks and on the rear glass hatch, German BBS spoked alloy wheels, and minor changes to the grille. The top two horizontal grille slats matched the body colour, and the door mirrors had electrical adjustment. Rare for the era was fitment of an on-board computer in the Turbo.

Robert Opron — the man who styled the Citroën CX and legendary SM — and Michael Jarden were the two designers behind the Fuego, thus explaining why the Renault’s glass clamshell rear hatch mimics the SM. Cynics reckoned that the car should be pronounced ‘few-go’ because few did, but that’s bit unfair.

Land of fire

Named after the Terra del Fuego, or ‘land of fire’, in South America, the French coupé was, appropriately, built in Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela, in addition to France, and became a bestseller in South America, unlike in the US, where sales were mediocre. The total production of 265,367 was less than Renault planned, and the company described the car as a “commercial flop that people liked”.

The North American versions came with oversize bumpers and different headlights that looked less elegant and raised the cd to 0.35. Around 20,000 were sold in the US through American Motors (AMC) dealerships by people accustomed to selling AMC Concords and CJ-7 Jeeps, and they were serviced by ill-equipped, ill-prepared mechanics.

Naming the Fuego after a Spanish word for fire could be considered ironic, as the car had something of a reputation for catching alight. There was a recall for steering-wheel failures, leaky head gaskets, and electronic gremlins, and the sometimes-poor build quality is perhaps why the Fuego is rare today. As they aged, there were leaking dampers and perished suspension bushes, yet Renault had learned many lessons about corrosion, so rust was rarely a major setback.

Unfortunately, most Fuegos today seem to be in this situation

However, there were occasional creaks and groans, which we experienced in two near-new examples tested on New Zealand roads, an annoyance also reported by some overseas owners. One chap, frustrated by problems with his Fuego, rather unkindly retorted, “Once you own a French car nothing worse can happen to you!”

Local attraction

Still, here was a striking-looking two-door hatched coupé that achieved fame in the 1985 James Bond movie A View to a Kill. It was also the car that attracted the attention of Auckland motorsport enthusiast Peter Gunther, a South African who has lived in New Zealand since 1998. He kept an eye on a modified Fuego on Trade Me and, eventually, the price became too good to resist. These days, the odd rare Fuego on offer is usually advertised with the message “bring a trailer” and this was, indeed, what Peter had to do to retrieve his example from its former home in the Manawatu. Now he has the Renault up and running to compete in the local European Racing Championship series.

His 2.0-litre GTX had been used as a Targa car and upgraded with a pair of side-draught Weber carburettors; a warmer camshaft, adjustable competition springs; a full roll cage; and cross-drilled, ventilated front discs. Peter is conscious of the car’s weight and intends replacing the extensive glass area with Perspex windows, while also disposing of the heavy electric-window mechanism. The Fuego suffered flywheel failure at Pukekohe last season, so the idea of acquiring a second Fuego as a spares-backup seemed logical. Peter found a second Fuego in Christchurch, but now intends to get this car back on the road as a daily-driver. He may well be the only person in New Zealand with two Fuegos, and he is certainly alone in circuit racing one.

Combine vehicle weight with relatively modest power, and the Fuego’s competition potential would always be limited. In addition, the car is somewhat nose-heavy, with a 62:38 weight distribution. This explains why it is all too easy to induce wheelspin during rapid standing starts. However, it is a brisk and satisfying road car, especially with the more powerful engines.

The 1.6 GTS develops a modest 72kW (97hp), while the 82kW (110hp) 2.0-litre GTX with alloy block-and-head engine and Weber twin-choke carburettor would be a better bet. The 1565cc Turbo produces 98kW (131hp) and, with 200Nm, boasts 23-per-cent more torque than the GTX.

The Turbo uses a development of the R18 Turbo saloon motor, and, by further lowering the compression ratio from 8.6:1 to 8.0:1, Renault was able to increase turbocharging boost pressure from 9psi on the R18 to 11psi. The pushrod overhead-valve motor is fed by a single Solex carburettor with a Garrett T03 turbo, and, like all Fuegos, the power plant is mounted longitudinally. Power delivery is peaky and there is some initial lag. Acceleration is not appreciably better than the 2.0-litre GTX, although top speed increases from 183kph to 200kph, and the run to 100kph takes 8.4 seconds compared with 10 seconds. All have front disc brakes, while the Turbo has larger ventilated front discs and solid discs were added at the rear.

Expect a slightly notchy gear change and avoid the optional automatics, which were also imported locally. The GTX engine is extremely flexible and happy enough pulling away from as low as 20kph in fifth gear. Yet this lack of refinement contrasts with the low wind noise, a consequence of the fine aerodynamics and good door and window sealing.

Slippery shape

During the entire life of the model, there were no significant changes made to the body shape. Small revisions in early 1983 consisted of a sealing lip under the bonnet, above the grille; a deflector in front of the radiator to improve airflow; revised sill guards ahead of the rear wheels; and a central deflector under the floor — Renault was serious about the car’s slippery shape.

Thirty-five years ago, I was immediately struck by the French charm during my first Fuego test. This was Renault’s answer to the Ford Capri, Toyota Celica, Volkswagen Scirocco, Opel Manta, and Audi coupé (with which it shared the same 4358mm length). The car was based on the Renault 18, with the same floorpan and front-wheel drivetrain, and, while the suspension is identical to the 18’s, few parts are interchangeable. The front suspension is by double wishbone, and the rear axle is located by trailing links and an A-bracket. I noted a firmness to both ride and response, and the rack-and-pinion steering was nicely weighted, with the power assistance eliminating much of the front-drive feeling. The Fuego impressed for its stability and high-speed ride and was not at all perturbed when crossing railway lines or striking potholes.

Pirelli P6 tyres fitted to the 14-inch rims were standard, helping to make the car feel nimble.

In true French tradition, the coil-spring suspension had long travel, and it coped well with all road surfaces, though ride did tend to be firm at slower speeds. At the same time, body roll was a lot less than it was in many older French cars. Engine noise was a little intrusive under acceleration, but the car was quiet and relaxed when cruising, and the comfy front seats, with their pinstriped velour upholstery, heavily sculpted backs, and extended sides, provided excellent support.

Pantograph-type wipers swept right to the driver’s edge of the sharply raked windscreen, and I found the controls clear and clean. The steering wheel adjusted for rake but not reach, and ventilation was good. The huge rear window, which had minor optical distortion because of its shape, was swept clear by a wiper that did not need much use, since the glass would stay remarkably clean on a long journey.

What was once considered to be a ‘cutting edge’ space-age style dashboard found inside the Fuego

Deep side windows provided a generous view, although the heavy rear quarter panel provided a blind spot, and frontal visibility was slightly impaired by the pronounced windscreen rake. Headroom was not over-generous and rear-seat legroom was limited, but, overall, the Fuego was practical with its split folding back seat that could be removed entirely, squab and all. There was no external tailgate release; this could only be operated from the driver’s door jamb.

Initially, the New Zealand market took the $22,241 overhead-valve 1647cc GTS model in 1981, followed two years later by the $24K single-overhead-cam 1995cc GTX. By mid-1984, the price of a 2.0-litre GTX had risen to $26,720, and automatic options were available for both. The first of the manual-only Turbos in March 1984 retailed for $37,600, and, when it was last imported in October 1986, the new list price had raced to $44,200, compared with $40,100 for the GTX manual. An electric sunroof and leather upholstery were useful extras for the last of the Turbos.

Today, the price of a Fuego is only as much as the purchaser sees fit — which may not be much — but ponder the Turbo, which is the one to have. In Britain, two years ago, Fuego Turbos were worth loose change, yet now, good ones command more than the equivalent of $25K.

Renault built an upmarket convertible prototype with leather upholstery but decided against production. Plans for a second-generation Fuego were scrapped after European sales of all coupé models slipped, and Renault faced an economic axe. However, the original soldiered on in South America until 1992, six years after production ended in France.

To some, the Fuego is a forgettable experiment and a lost car of the ’80s, yet, despite the foibles, it remains a cool and quirky classic with potential for appreciation.