Daytona Beach — it even sounds evocative

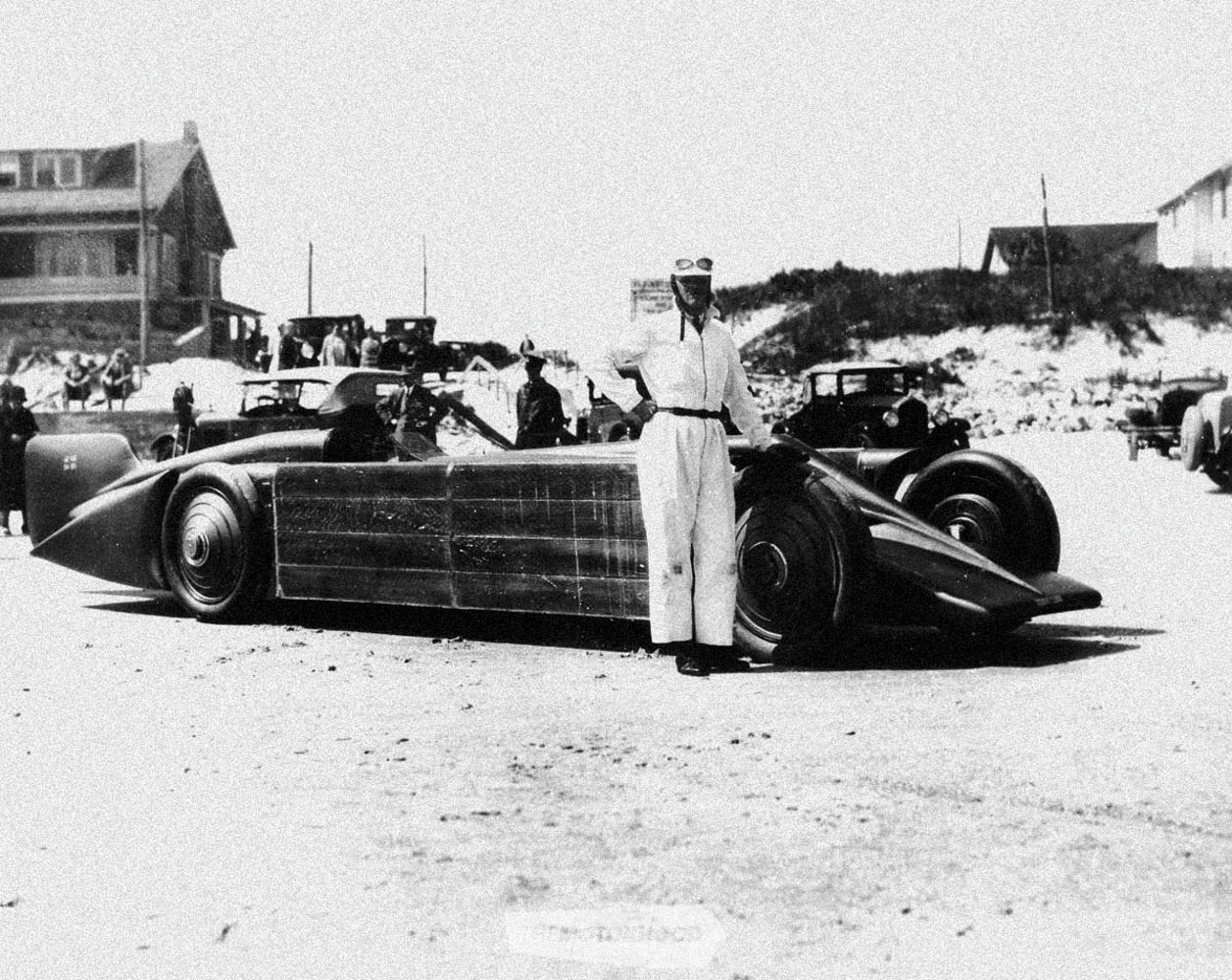

The unusually hard, compacted sand and wide beach at Daytona had been noted, and, as early as 1902, it was being used for car and bike races — but it was land-speed record attempts that really captured the public’s attention at the turn of last century. Not only was the beach wide, it was long — some 37km — and, in 1904, William K Vanderbilt set an unofficial record of 92.307mph (148.554kph) there. This didn’t escape the notice of British speed pioneers Sir Henry Segrave and Sir Malcolm Campbell, and, in March 1927, at Daytona, the former set a new world record in his 1000 HP Sunbeam at 203.80mph (327.97kph), becoming the first to crack 200mph. Two years later, aboard the magnificent Golden Arrow, the American-born Irishman was back at Daytona, where he nudged the record to 231.45mph, or 372.48kph.

Campbell broke five land-speed records at Daytona but, by the early 1930s, had concluded that the surface was not as smooth as the Salt Flats of Bonneville, and he took his Bluebird off to Utah. In September 1935, he set his final speed record there, becoming the first man to exceed 300mph, averaging 301.345mph (484.955kph) for the two passes.

Daytona might have been done for record attempts, but city officials, anxious not lose their main claim to fame and to keep the restaurants and hotels busy during the off season, organized races on a 3.2-kilometre (5.1-mile) track in 1936.

A year earlier, a young aspiring racer had moved his family to Daytona from Washington DC to escape the Great Depression. He was nearly penniless, but Bill France was a hard worker and already using his entrepreneurial skills to fund his racing. The races were primarily for street-legal sedans, and France was prominent until he realized that his future was as a promoter. After the war, crowds had grown to the point that it had become obvious that a permanent track was needed, and, in 1953, he announced plans not just for a mere circuit but a superspeedway.

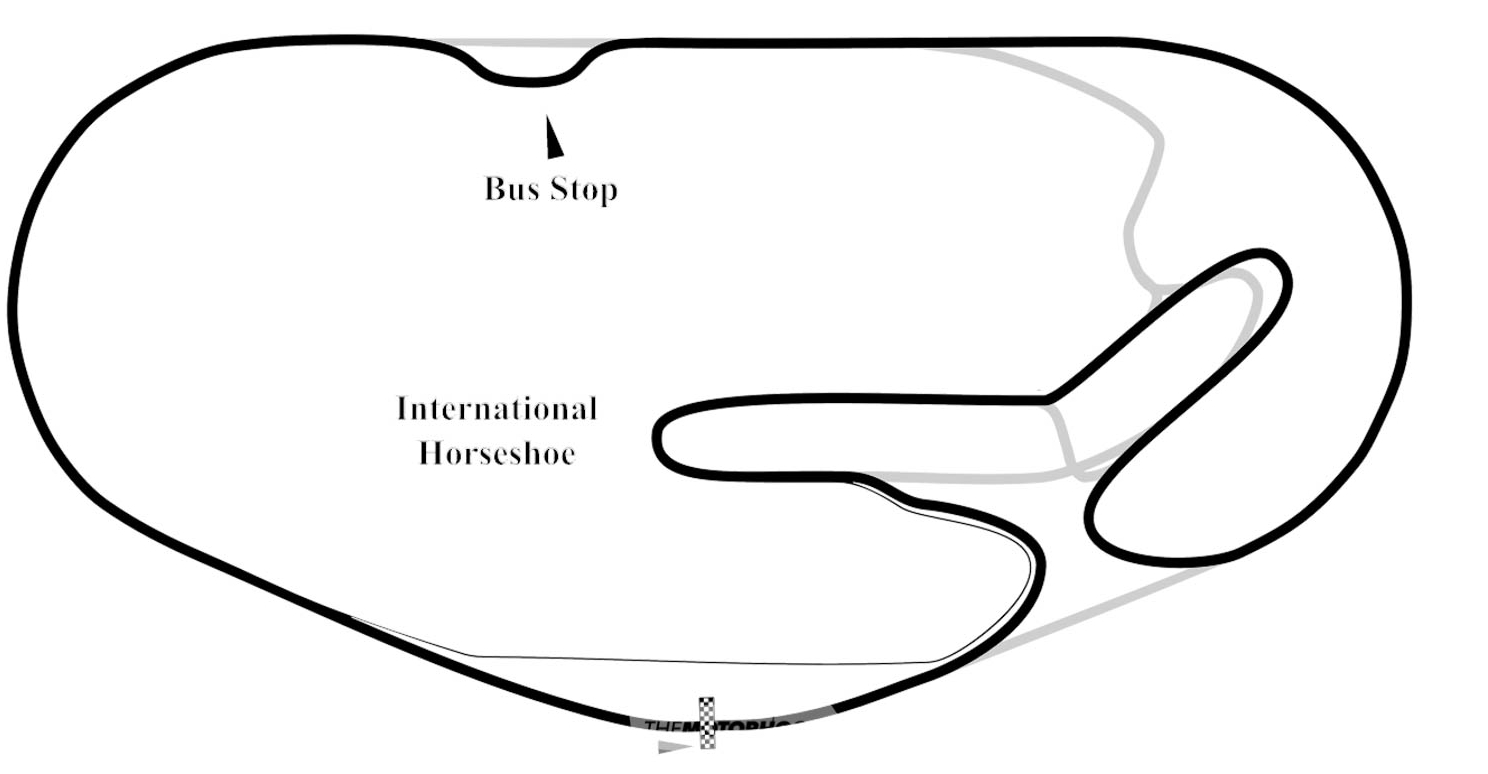

Work on the 2.5-mile (four-kilometre) ‘tri-oval’ started in 1957, and the inaugural Daytona 500 was run in February 1959 — and it remains the track’s premier event. France had founded Nascar in February 1948, and the phenomenon that is the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing is still a family business, being second among sport franchises — behind the National Football League — for US TV audiences. France had foresight, and incorporated a road-course option into the design, which lengthened a lap to 3.81 miles (6.13km). A three-hour race for sports cars was first run in 1962 and was extended to a full round-the-clock event in 1966.

Kiwis at Daytona

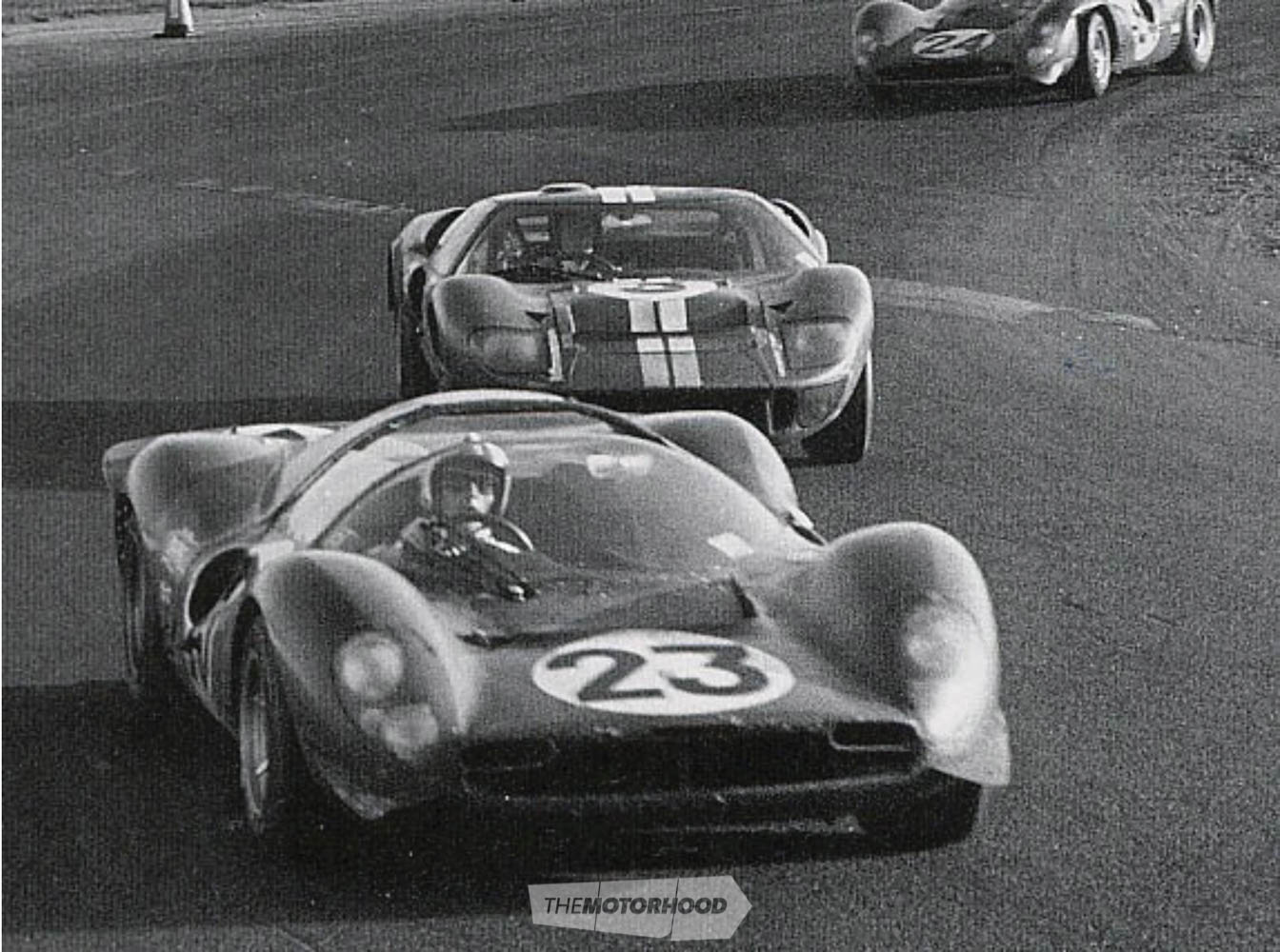

It took until 1966 for a Kiwi to make a start at Daytona, when the entire trio turned up — Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon in a Shelby American–entered 7.0-litre Ford MkII, while Denny Hulme had his one and only ever race aboard a Ferrari (a 3.3-litre 275LM). Fords finished one-two-three, while the best of their Italian arch rivals, Ferrari, was fourth. Bruce and Chris were fifth — in a hint of what was to come at Le Mans in June. For the 1967 race, all three Kiwis were in potentially race-winning cars. Bruce was still very much one of Ford’s anchors and, following the decision of his young compatriot to head off and join the opposition, was now paired with Italian-born Belgian Lucien Bianchi. Ford split its six cars equally between ‘Shelby’ and Holman and Moody, and it was for the latter that Denny was paired with Indy 500 hard nut Lloyd Ruby.

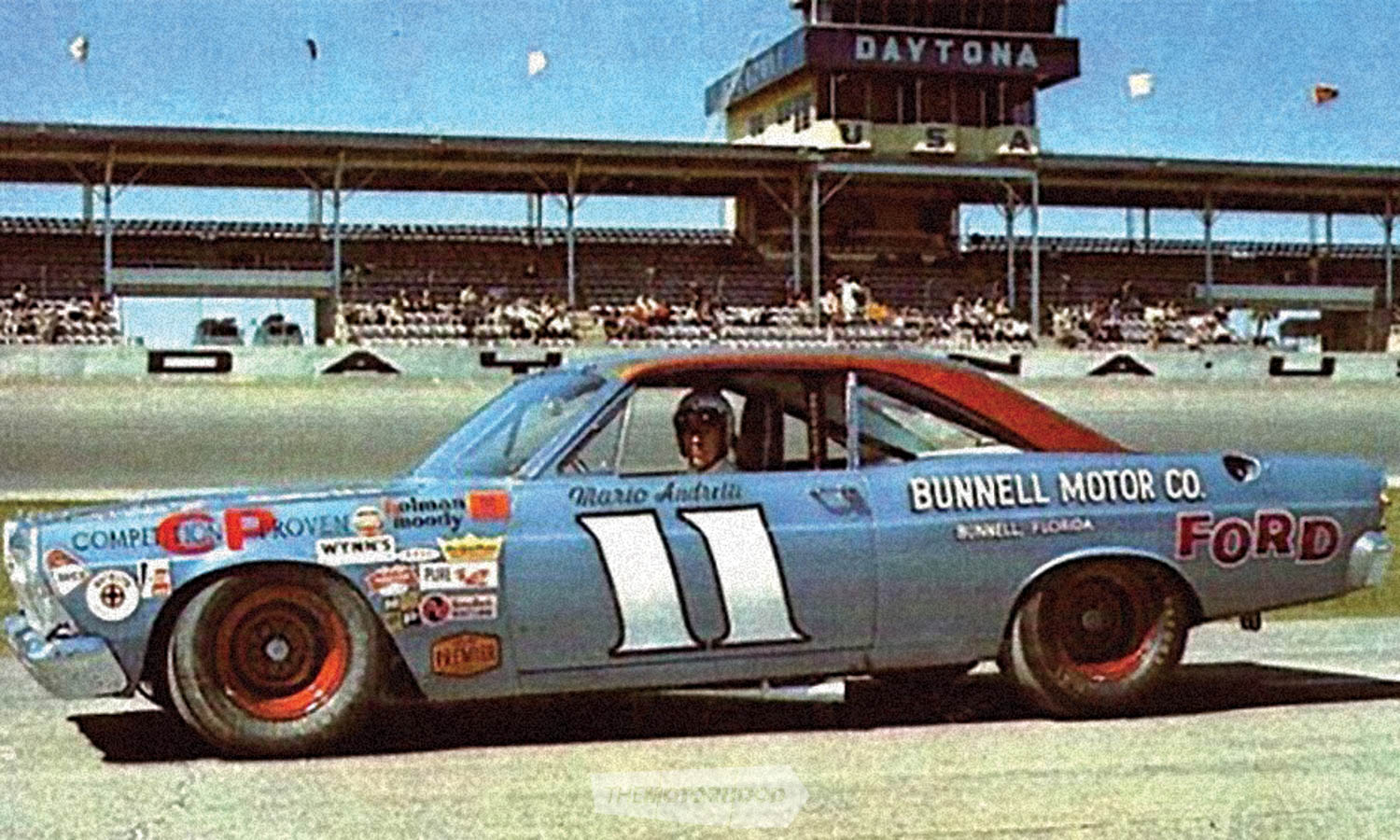

The other works Fords had pairings of Ronnie Bucknum / Frank Gardner, Dan Gurney / AJ Foyt, Mark Donohue / Peter Revson, and Mario Andretti / Richie Ginther — it was a formidable line-up, and Ferrari only had half the number of frontline cars. Whereas the Fords were built around its huge 7.0-litre (427ci) V8, the Ferrari ran a 4.0-litre V12 — a pure racing engine against the big ‘stock block’. The only top driver to ever experience both was one of our own, and Chris recalled the two approaches clearly — “I always thought those 7.0-litre Fords were pretty good, apart from the brakes, until I drove the P4 … not only did it look fantastic, it was like a thoroughbred in comparison.”

The approach from Ferrari had come via Shell’s PR man, who asked Chris, “Would you like to come to Italy with me to meet Mr Ferrari?” That enquiry came at Watkins Glen in October 1966, where Chris was spectating. He was doing Can-Am with Bruce after the anticipated second McLaren Formula 1 (F1) car had never come to fruition, because of engine issues. Chris has never denied that he felt terribly compromised — on one hand, he was with Bruce, to who he was grateful for having given him a chance, while, on the other hand — “This was Ferrari …” Not surprisingly, the 23-year-old New Zealander, with his deep historical knowledge of the sport, was completely in awe of Ferrari, but recalled that “[a]fter the contractual stuff was done, we headed over to the Cavallino (restaurant) across the road for lunch. I drank mineral water and he said through his interpreter that it was always interesting having lunch for the first time with a new driver …”

1967

It had long been Ferrari’s way to pit drivers against one another, so as to extract their best. In signing with Ferrari, Chris knew there was no guarantee that he’d secure one of the F1 seats — and that he was up against three established Ferrari men, two of who had the advantage of being Italian. Lorenzo Bandini started with the Ferrari team in 1962, was dropped then rehired in ’63, and won the Austrian Grand Prix for the ‘Scuderia’ in 1964. Despite a pole and two fastest laps in 1966, his best finish had been second. Ludovico Scarfiotti had won the 1966 Italian Grand Prix ahead of Englishman Mike Parkes in a Ferrari one-two, but both were more all-rounder than ace.

Chris: “When we did the testing at Daytona in December, Bandini and I were quicker, and I’ve got to say I was trying to make sure I was in front for the F1 drive. I’d also had an advantage in that I’d spent a lot of time at Daytona with Ford, so I knew my way round.”

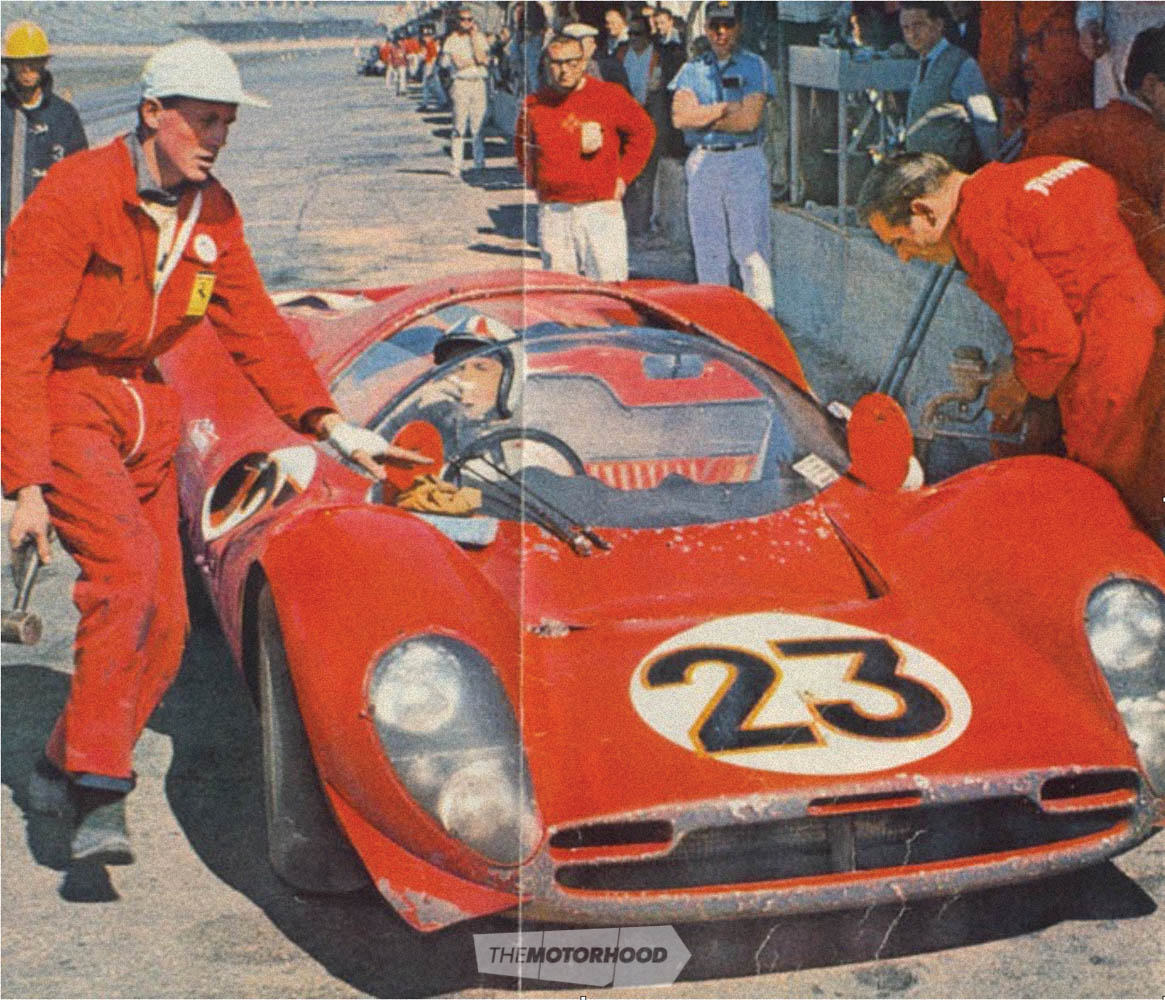

With Bandini looking very much like the top dog, Chris had sussed out that the driver pairings might be as much his decision as team management’s — “I’m not sure he [Bandini] was the greatest of mates with [Mike] Parkes or ‘Lulu’ [Scarfiotti] — they got on all right, but I don’t think they were bosom buddies.” Chris’s wish came true — he and Bandini would share car 23, while the taller Lulu was partnered with the 1.93-metre Parkes in car 24. Qualifying revealed another challenger to the Ford-versus-Ferrari battle in the form of all-white Chaparrals with their big-block Chev V8s. A red car took pole for the 1967 24 Hours of Daytona, but it was a Ford not a Ferrari. One of the two Chaparrals was next, followed by a pair of Ferraris, another Ford, and the Parkes/Scarfiotti P4 in sixth. The Bandini/Amon car was fourth quickest, meaning that Chris was ahead of both the other Kiwis — Bruce’s yellow Ford was seventh quickest, while Denny’s silver version was ninth.

Chris: “The Ferrari was so much more nimble. Obviously it didn’t have as much torque or power, but at Daytona we could run rings around the Fords through the infield, and they were quicker on the banking.”

The first Ford to encounter gearbox problems dropped out just after one-third distance. The breakages then came thick and fast: the car Denny was sharing went out before half distance, by which time only two of the 7.0-litre MkIIs were still running. Then the Gurney/Foyt pole car retired (a non-cooperating con rod for a change) leaving just the McLaren/Bianchi car representing the blue oval. The Bandini/Amon car had clearly got the upper hand, and they finished a clear three laps ahead of their teammates, with a semi-works Ferrari a distant third. Ferrari had rubbed Ford’s noses in it on home soil, and it didn’t go unnoticed.

Another thing that hadn’t gone unnoticed was that Chris Amon had now won both of the 24-hour sports-car races before his 24th birthday, and the win at Daytona had come some seven months after Le Mans. By the early 1980s, it had become standard practice to use three drivers per car at Le Mans, as improved reliability turned the event increasingly towards a sprint rather than a steadily paced enduro — however, that had already become the norm at Daytona. Indeed, five drivers shared the winning Porsche in 1968, but although Le Mans had the prestige, Daytona was widely regarded as the tougher race. Fifty years ago this month, we had three drivers in with a chance — and one very happy one at the end who started off his new life driving for the world’s most famous racing team, in the best way possible.

Nationalities

While sitting in the grandstand at Indianapolis in 2000, it occurred to me that we might be about to witness history, other than the obvious thing of seeing F1 cars on the famous track (or at least a bit of it) for the first time. It started to drizzle, and whereas any hint of precipitation sees Indycars heading to Gasoline Alley, the Grand Prix cars pressed on regardless. It was time to dig into my backpack and extract my trusty Bruce McLaren Trust shower jacket, leading my newfound friends in the adjoining seats to conclude that I was presumably a fan of the team, because they’d remembered Denny Hulme and Chris Amon driving for McLaren in Can-Am as also being Kiwis.

This couple, from Northern California, were serious fans and had seen the orange sports-racers dominating the category in the ’60s and early ’70s. I acknowledged that my raincoat was in honour of Denny and Chris, but, of course, Bruce as well. They looked shocked. They glanced at one another and then back at me — I wondered if they had smelled something I couldn’t, and they’d imagined it had come from me. Eventually, ‘Mrs Racefan’ let out “… but Bruce McLaren is British.”

I was reminded of this while researching the story on the 1967 24 Hours of Daytona. The programme lists the driver’s home town — some are quite specific, for example, Frank Gardner’s is given as Palm Beach, Sydney, Australia, whereas Chris’s is rather more general — New Zealand. The man who, come the end of 1967, would be crowned world champion, is also shown as from New Zealand, but he is recorded as being ‘Dennis’, not ‘Denis’. Bruce, however, is shown as being from Colnbrook, England. Perhaps it should come as no surprise, after all, that some Americans assumed he was British.

The Tasman

Seeing as how I’m stuck in 1967 this month, and having just referred to the fact that Denny would finish 1967 as world champion, I couldn’t help but notice how little indication there was of that eventuality when looking at the results from that year’s Tasman Series. In January, Jackie Stewart’s BRM had beaten Jim Clark’s Lotus at Pukekohe, but the senior Scot won at Wigram, where Denny was third. In the first of the four Australian rounds, after returning from Daytona, he was fourth at Lakeside and then failed to finish in the next three. His teammate Jack Brabham fared little better, although at least kept his 2.5-litre Repco V8 together long enough to win the finale in Tasmania. Clark was easily champion, while the Brabhams, which had defied all the odds to win the 1966 World Championship, looked hopeless.

What were the odds in February 1967 that the Repco-powered Brabhams could win another title? And what must have been the odds if they did, that it would be a Kiwi winning top honours, not his Australian teammate/boss?

This article originally appeared in NZ Classic Car issue No. 314 — Click the cover below to purchase a print copy of the magazine