data-animation-override>

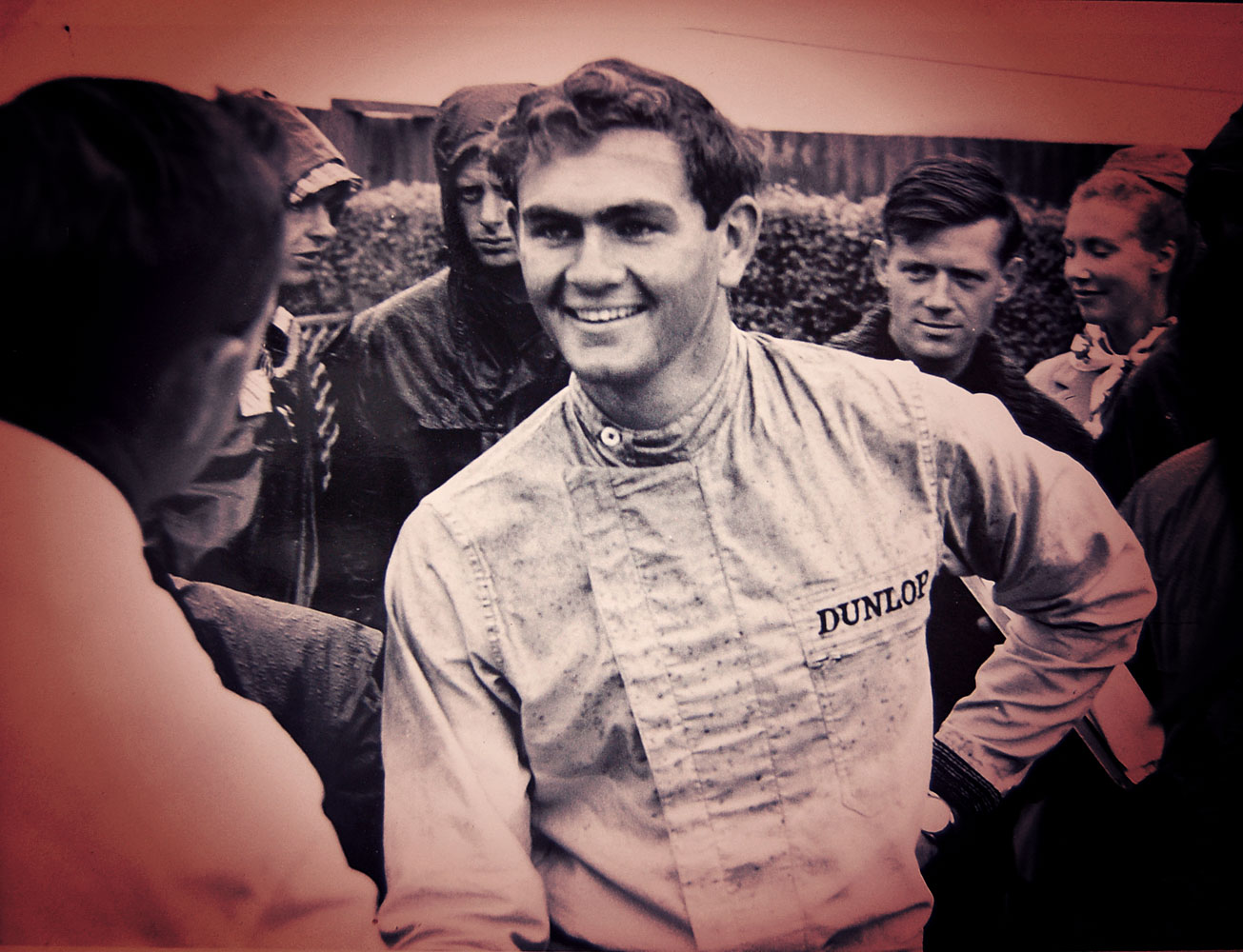

“After five years of top-level motor racing in New Zealand, Andy Buchanan walked away with no regrets. He tells Gordon some of his story”

Photo: Euan Sarginson

Cars and aviation were in Andy’s blood. His father flew Tiger Moths between the two World Wars, and was killed during World War II when his Kittyhawk was shot out of the sky over Rabaul. Andy was just 15 months old. He and his older brother, Hamish, were brought up by their mother, a formidable woman who also ran the family farm.

Hamish — who raced Minis — and a family friend in the Wanganui Car Club influenced Andy’s first foray into motor sport as a 20-year-old, in a saloon car race at Levin in January 1962. He had bought a new Austin A40 Farina and made a few modifications to it, including fitting twin carburettors. Unbeknown to him, pundits were taking bets on how many laps he would complete. The answer was three, before he crashed the A40 spectacularly at Hokio Bend. The Austin rolled five times, with Andy being thrown from the car. He was hospitalized with crushed vertebrae, which caused problems for many years.

For his second attempt, Andy bought a Buckler from Scott Wiseman. He soon discovered this car, which was powered by an Elva-modified 1172cc Ford engine, was totally worn out. Having circulated slowly in a few races, the final straw came when it put a con rod through the engine block on the Takapau Plains. When he later stumbled across Wiseman polishing his newly-imported lightweight Jaguar E-Type in the pits at Pukekohe, Andy loudly told him he’d promised himself, “If I ever see you again I’ll kill you.”

He didn’t, but it got the attention of others in the pits.

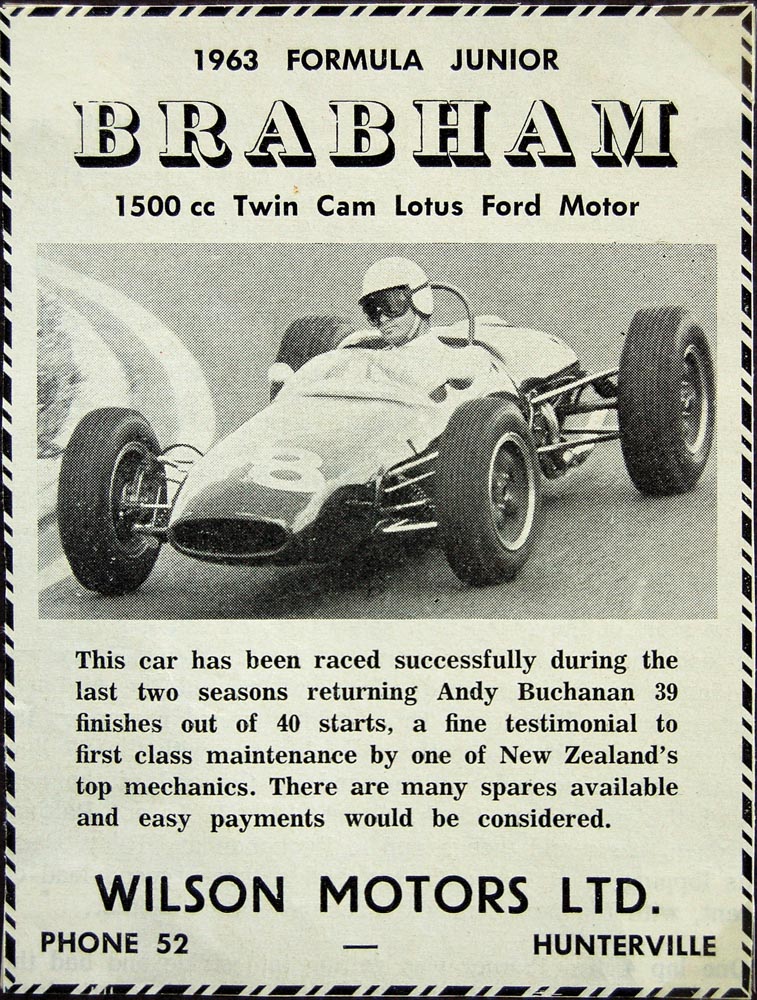

New Brabham, no money

Andy headed off to do his Kiwi OE, working as a shearer and fencer in England. He became friends with David Mills, who worked in the office at the Brabham factory, and they often went out out drinking together. To his consternation, Andy woke up one morning and realized he’d signed up to buy a new Brabham BT6 Formula Junior car. The purchase price of £5000 included the Lotus twin-cam engine that Brabham, Denny Hulme and Mills said he needed. There was a minor problem — Andy was being paid little more than subsistence wages, and he had no money to speak of!

Two aerogramme pleas for help to Mrs Buchanan saw the Brabham paid for, and shipped to New Zealand in time for the Renwick race meeting in November. Andy had no trailer or the slightest idea how to look after a proper racing car. However, while he was in England he’d renewed his friendship with a former school mate, Chris Amon, and he suggested that Bruce Wilson, Chris’ former mechanic (and later to be his Tasman Series mechanic) might look after the car. Chris even offered Andy the use of a trailer. As far as Andy knows, his was powered by the first Lotus twin-cam to come to New Zealand.

Andy’s first drive in the Brabham was on the roads around Bruce’s home base of Hunterville. It was his first time in a single seater, and he was initially disconcerted by the sight of the wheels bobbing up and down. A short while later the local barber was ranting about hooligans careering around on public roads in racing cars. Andy wasn’t game to own up.

It was a good season, starting with a sixth place on debut in the Renwick 50. A seventh in the New Zealand Grand Prix, against 2.5-litre Tasman Formula cars, was also a worthy result. Numerous podium places and a few wins netted Andy fifth spot in the New Zealand Gold Star Championship. His win in the wet Waimate 50 is regarded as one of his best drives.

Andy recalls the Brabham’s Hewland gearbox used to strip teeth off first gear, and Bruce would painstakingly weld them back on and reshape them. He complained loudly and frequently to the factory about this. At Pukekohe, Jack Brabham called him over. “Come here boy, I’ve got something for you.”

“Beauty!” thought Andy, “I’m getting a good first gear.” Not quite. Jack gave him a tiny tie pin!

Boys will be boys

Those were the days when things were serious on the track, and there was a lot of fun off it. After one meeting Andy and Chris Amon, and possibly others, somehow came to be dancing on the roof of Andy’s ‘high-line’ Zephyr MkII — it had a ‘low-line’ roof by the time they’d stopped. “Chris slid off the roof and down the boot, landing astride the towbar, and I reckon that’s why he was so fast,” jokes Andy.

At one Mount Maunganui meeting, Andy used his Chrysler Valiant tow car to nudge drums set out along the edge of road works near the circuit, tipping each drum on its side. That night some of the other racers thought they would try the same trick. Unbeknown to them, the road workers had filled the drums with water. There were some dented cars and red faces next morning.

Things were a bit different for the 1964–’65 season. With the opposition stepping up to newer and/or bigger cars, the Buchanan team had its work cut out. Andy still managed a fifth in the Renwick 50, seventh in the NZIGP, Levin International and Lady Wigram Trophy, races that counted towards the Tasman Series. He was third in yet another soggy Waimate 50, won at Matamata, and made the podium in the Zambucka Memorial Trophy race at Levin. He finished the season with a third place in the Gold Star Championship, and second in the National Formula for 1.5-litre cars.

It was another satisfying season, but the writing was on the pit wall. Although the little Brabham had something like 39 finishes from 40 starts, many near the front, it was clear that a 2.5-litre car was needed if he wanted to remain competitive.

Anti-Climax

Andy bought Jim Palmer’s Climax-powered Brabham BT7A, and couldn’t resist noting that Jim hadn’t paid the required import duty on the car. It did, however, come with a proven history. Denny Hulme had used it to good effect in the 1964 Tasman Series as a Brabham works car, and Palmer enjoyed an equally successful season in 1964–’65. Somehow, Andy couldn’t sustain that success. A frustrating succession of ‘did not finish’ results (DNFs) often resulted from broken cam followers. He also broke his crankshaft at Warwick Farm while racing during his honeymoon (!) and the engine popped its distributor out at Sandown Park. Andy ruefully describes that engine as more of an anti-Climax.

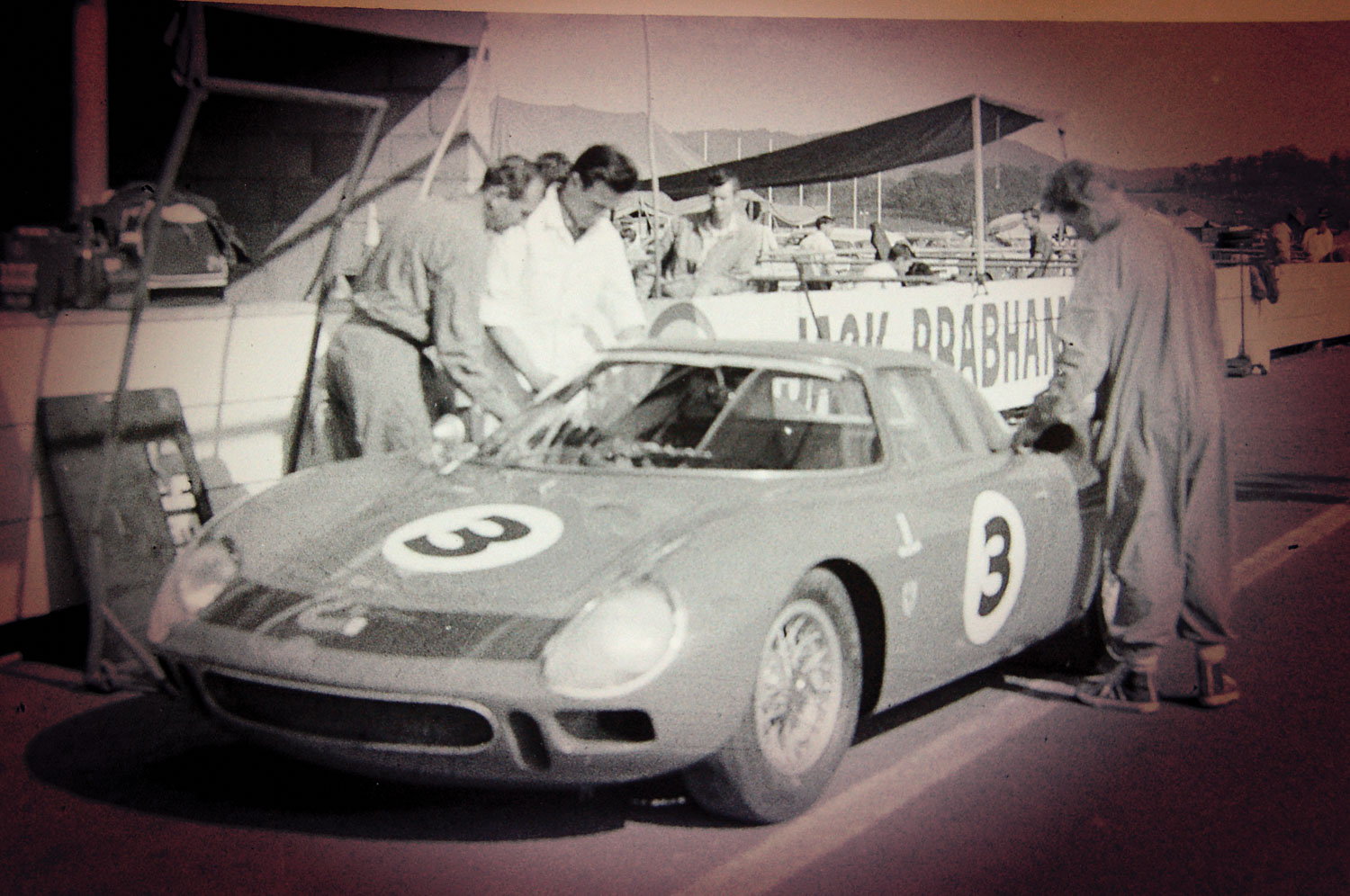

The season’s end was really a relief, and the BT7A was sold. Andy contacted David McKay, noted Australian motoring journalist, and founder of the successful Scuderia Veloce racing team. David had a newer Brabham that Andy wanted, but David wouldn’t sell once he found he couldn’t get a new car from the Brabham factory. However David, with his well-known speech impediment, said, “I have this F-F-F-Ferrari I don’t know what to do with.”

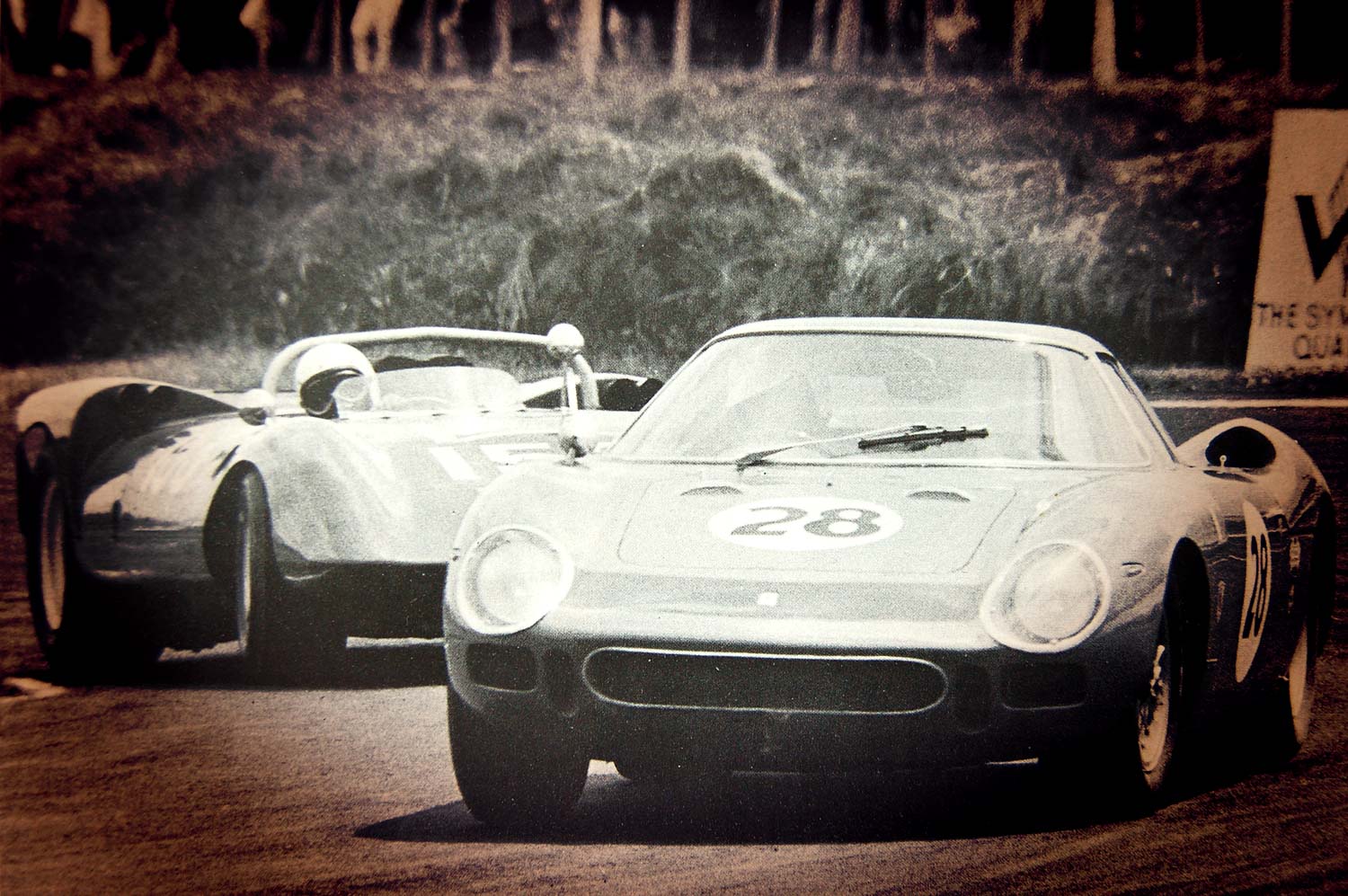

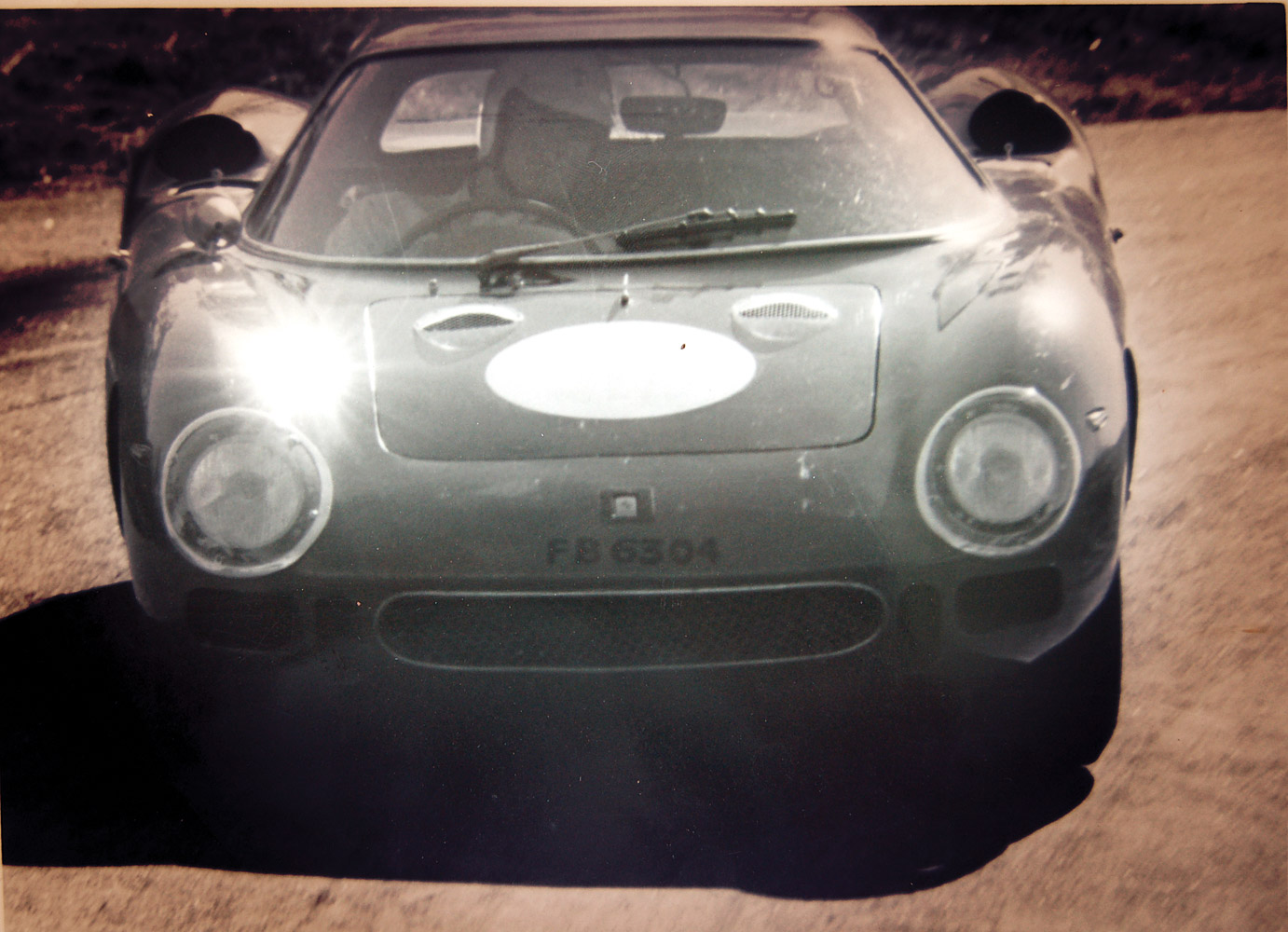

It was a 250LM, really a 275 because it had a 3.3-litre V12 engine rather that the 3.0-litre version. Spencer Martin brought this car to New Zealand for the 1965/’66 summer season, winning the Wharton Memorial race at Pukekohe, the Gold Leaf Trophy at Wigram, and the DR Filter Trophy at Teretonga.

Photo: Euan Sarginson

When the 250LM was returned to Australia, Andy drove the Ferrari at Bathurst, hitting 280kph on Conrod Straight, where the car would lift on a rise. This terrified him, because he remembered reading about a driver who had been killed when his Porsche lifted at that speed on the same rise and was blown into a tree.

Tall and short

In August 1966 Andy partnered with Jackie Stewart to win the Rothmans 12 Hour endurance race at Surfers Paradise. Andy had been 1.88m tall prior to his A40 crash, but although perhaps a tad shorter he was still tall, and the diminutive Jackie took one look at his co-driver and observed that one of them was going to be uncomfortable. Perhaps that’s why Jackie used a full harness, while Andy used a lap and diagonal safety belt.

As well, there was something dangling from the ignition key, and Jackie was most insistent that it had to be taken off. “You don’t want that swinging around if you’re going cross country at 130mph [209kph].”

With Stewart and Andy at the wheel, the 250LM won the race — although there was some dispute over the final results.

Later that season Shell flew Andy first-class to Perth for a six-hour race at the Caversham track, with high expectations of success. He was late getting to the track and missed practice, but in the race he was 14 seconds a lap quicker than the next car. A kangaroo bounded onto the circuit in front of the Ferrari while the car was travelling at 240kph, and Andy missed it by a whisker. Then it started raining and the LM was hit by another car — that damaged the right rear wheel bearing. Andy brought the car into the pits to retire. When he reported what had happened, McKay’s chief mechanic, a very religious man, responded with, “Bum bum!”

Maranello masterpiece

Having done that single season in New Zealand in Spencer Martin’s hands, the Rothmans 12 Hour race, and many others, all without a major overhaul, the Ferrari now cried enough. At Sandown Park its catch tank filled with oil and the 250LM expired. The car was subsequently overhauled and put back into race-ready condition — it was at this point that McKay offered the Ferrari to Andy for £5000, although actually paying for it would’ve been something of an issue back in those days of currency restrictions.

Although Andy wouldn’t actually purchase the 250LM, he was entrusted to bring it back to New Zealand for 1966/’67 — and he enjoyed a very successful season, winning the New Zealand Sports Car Championship after a season-long tussle with Jim Boyd in the Lycoming Special, and Geoff Mardon in the Stanton-Corvette. This was the first real challenge to the Lycoming for several years. To be fair, Andy sometimes had an easy time of it, especially if one or both of the others retired from a race. At an Auckland Car Club meeting at Pukekohe, he ran away from the field, twice lapping the third-placed Jaguar XK120. The 250LM’s final appearance in New Zealand was at Timaru, where Andy won the Sprague Motors Championship race.

Photo: Gerard Richards

He returned the LM to Australia, where it won another two Rothmans 12-Hour races for Bill Brown and Greg Cusack in 1967, and the Geoghegan brothers the year after.

Back in New Zealand, a typical call from David would be, “A-A-A-Andy, I-I-I-I’ve entered the LM at the F-F-F-F-Farm, I suggest you hop upon a kite and get over here.” ‘The Farm’ being, of course, Warwick Farm, and the call would usually come on a Thursday for a race on the Sunday. Andy fondly recalls the Ferrari as a lovely, very forgiving car, except for its fierce clutch and the almost total lack of flywheel effect. Nobody, no matter how good a driver, could get the car off the line for the first time without stalling it four or five times. It could hit 117kph in first gear.

Photo: Lance J Ruting

The 250LM would eventually end up as part of fashion guru Ralph Lauren’s extensive car collection. The Ferrari, along with many other cars from Lauren’s collection, went under the hammer at a Paris auction in 2011 — and fetched US$14.3 million.

Andy bought a new Elfin 400 to contest the 1967–’68 New Zealand Sports Car Championship. This lovely-looking monster was meant to have an all-alloy Chevrolet V8 engine, but it was powered by a 6.5-litre cast-iron Chevy instead. The Australian capacity limit was five litres, so he couldn’t race the car there. Andy reckons the engine weight caused the brake fluid to boil after a couple of laps, but that wasn’t enough of a handicap to stop him taking out the New Zealand championship again.

Moving on

Having ‘been there, done that’ Andy decided to quit motor racing. He walked away at the right time — at the top of his game. The Elfin was sold. Its trailer was converted to a pie cart, the engine went into a boat, and the car finally got its correct alloy engine.

Andy went back to full-time farming near Masterton, until the day in 1974 that a helicopter pilot took him for a ride to spray thistles. That was it. Andy had to have a helicopter!

He bought a Hughes 300 and, barely ‘out of his time’, a friend convinced him to join the booming live deer recovery industry. Their first attempt was a disaster, resulting in a large hind having to be jettisoned. Some of Andy’s stories explain why deer recovery operators earned a reputation as cowboys back in those early days. He wrote off a Hughes 500 in a crash, but unlike quite a few operators, he lived to tell the tale, and gave up in 1988 when there was no longer any money in the game.

Semi-retired in Assisi Gardens — an Italian-flavoured paradise high on a Wairarapa hill — with his second wife and two over-indulged black Labradors, Andy is still an avid follower of motor sport, particularly Formula One. He maintains the Ferrari link with a 456 road car, a stunning-looking car that he happily says is the most unreliable one he’s ever owned. On the positive side, its engine, brakes and steering are nothing short of brilliant.

Talking to Andy, there’s still evidence of the cheeky demeanor and devil-may-care attitude that got him into a few scrapes, and saw him spend so many years living on the edge. He still thoroughly enjoys life and finds it hugely entertaining, or makes it entertaining, just as he always did. Here’s a man who is comfortable in his own skin, satisfied with what he’s done and where he’s been.

Not forgotten

Five years in top-level national motor sport, racing against five world champions and living to look back on it, is a significant achievement, and yet Andy is almost unknown today. Not that it bothers him in the slightest. A scrapbook with a few cuttings, a photo album with some loose photos, a few more framed and hung on the wall, and one end of a broken Climax crankshaft used as a paperweight are the only visible signs of that time. Intangible but no less real are the full memory banks.

Motor-racing fans who witnessed Andy in action in the Brabhams, and especially in the glamorous Ferrari LM or purposeful Elfin, won’t need reminding that he was a champion — and he’s definitely not forgotten.