The F1 modeller

by Aaron Mai

Photography: Aaron Mai

Model car builders are a special group among car people, a group that get an extra kick out of their passion by merging it with their hobby.

A fine model car is like a song; it can transport you back to a specific time in your life or motorsport history. The scope within the scale-model world is vast, yet when you get to witness a super-detailed example it stands out like a mechanical watch in a digital world.

Tony Lyne has been building models for as long as he can remember, and he has realised his love for classic Formula 1 in spectacular fashion. As a teenager, Tony was drawn to the ‘elbows out’ style of racing required to keep cars of that era on Formula 1 circuits the world over and the technological race to improve them.

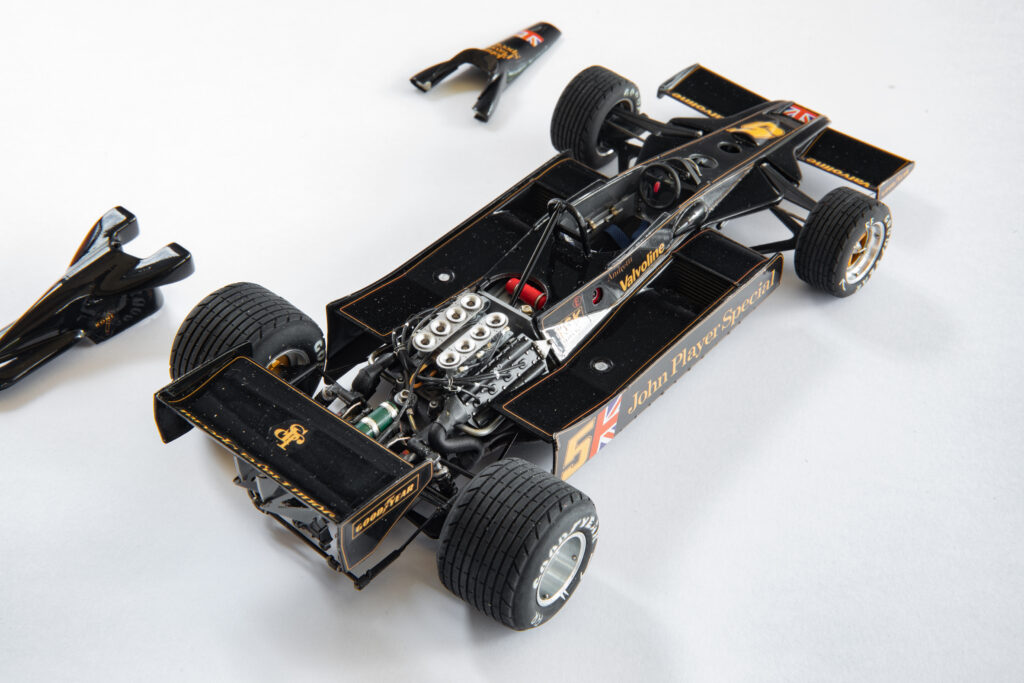

The open, mechanical beauty of the late-’60s to early-’90s cars made them perfect examples for model kitset companies to create and offer to adoring fans. Many of these kitsets have been produced in plastic via injection moulding, and, while the quality may be high in the better kits, the level of detail will at some point fall below what a dedicated modeller really wants.

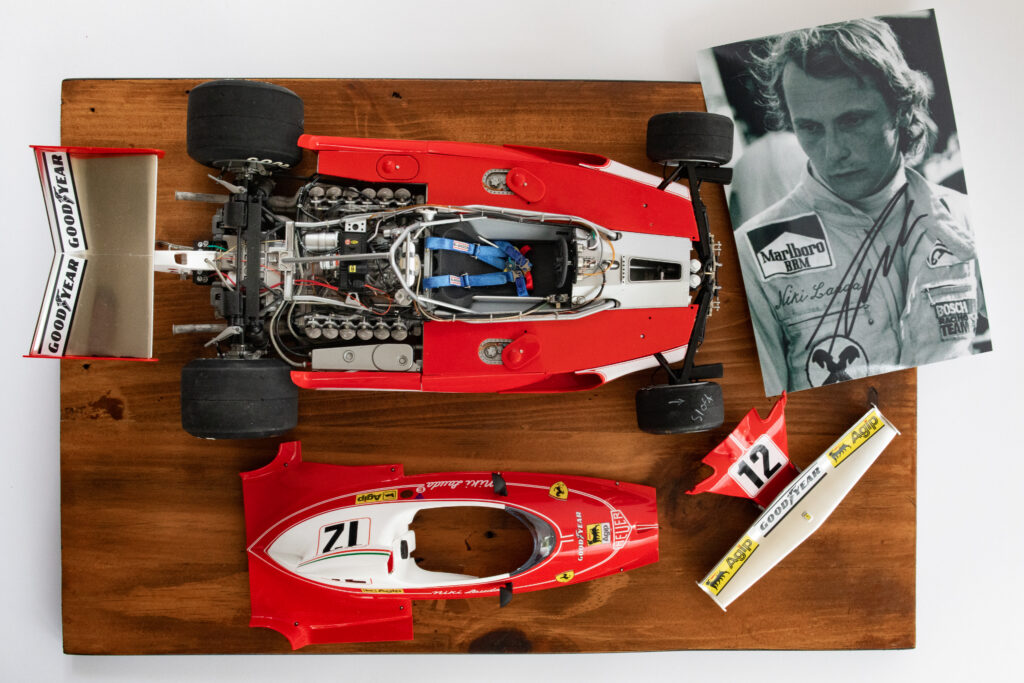

Tony saw these kitsets as a strong foundation just begging to have extra detail added to transform them into a much more satisfying representation — a creative process that makes them just as much a work of art as their oil on canvas counterparts. After poring over a 1:12 scale Ferrari 312T that Tony spent three months working on, I decided to sit down with him to learn a bit more about his deep commitment to the niche of super-detailed models.

Hi Tony, thanks for sitting down with me. First of all, what draws you to the art of scale models?

It’s the creation of something, and learning the engineering of the subject and how it worked. Also, I could never afford a real F1 car, ha ha.

Your builds focus on the ’60s to ’90s era of F1; what draws you to this period of the sport?

I see those as the glory years, and pure racing with amazing advances in engineering technology; [from] the engine being a stressed member of the car through to composites and the importance of aero and ground effects. It was pure racing, and the cars were all different and less prescriptive than they are today. I still love F1 but it’s certainly not the same as the glory days.

How did you get into scale modelling?

I have been involved with scale models from an early age in the early ’80s, when my dad took me to a model expo. I was hooked and joined the local club.

In your opinion, what makes F1 kitsets great for extreme detail builds?

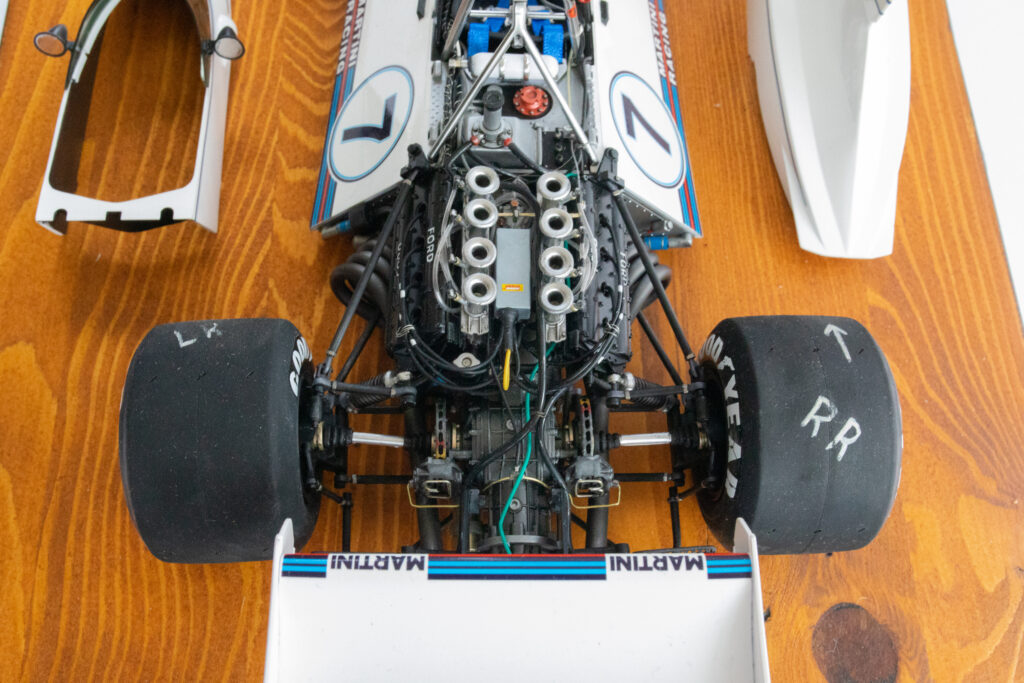

It’s the exposed nature of everything. In that era you could see everything and appreciate the engineering and how exposed the driver was. It’s then doing the research for the subject and building the missing components from the base kit. The challenge of fabricating parts is relaxing to me.

How long does a kit build take, from start to finish?

It depends on the scale, complexity, and level of detail. The 1:12 Ferrari 312T was a three-month build from start to finish, working most nights for an hour or two and then on the weekends. However, the Honda RA273, which is an original late-’60s casting, was badly deteriorated and warped. That build took a good 400-plus hours as there was a lot of hand fabrication and shaping of body components. I also needed to build a number of key mechanical components, such as brakes. The Lotus 78 and Tyrrell P34 are rebuilds of original 1970s castings and had a lot of missing parts. Key components like oil tanks and some body panels needed a lot of fabrication out of brass and solder, so those builds took about two months each.

Do F1 model kitsets go together in a similar fashion to the real cars?

On the whole they do go together like the real cars, where the structural integrity comes via the engine being coupled up to the monocoque and then suspended by the suspension components. On the high-end kitsets you have scale nuts and bolts that actually screw together just as they would on a real car.

How did you get into the extreme custom side of scale models?

I found detailing quite relaxing. When I’m building, I focus on the outcome and try to make it as lifelike as possible. That includes matching the paint finishes of the era — ’60s and ’70s race machinery didn’t have the mirror finishes of today. Super detailing is something I’ve always liked to do. When I started doing it as a teenager I overdid it, but I learnt the art of reining it in to make it more lifelike.

Models aren’t just plastic these days — tell us about the real metal inclusions.

Yeah, there’s various materials out there now. Most of the high-end plastic kits will have metal and resin components, especially in the larger kits where some of the suspension needs to be metal to hold the weight of the kit. Some kitsets on the market include photo etch sheet-metal parts for the sake of it, but you quickly figure out what is appropriate and what can be discarded.

There are some excellent detail kits available to enhance the builds; many can be expensive, so it’s often a trade-off to using aftermarket details such as turned alloy wheels through to fabricating your own parts, such as the bracing and struts on the two Renault builds I have done. The choice often comes down to cost and availability, as sourcing can be a challenge at the moment.

How much research do you do in order to obtain the level of detail you do in your kitset builds?

Google is your friend nowadays. There is a wealth of information on the internet for most builds. I’ll compare builds others have done, often learning from other builders how they dealt with specific parts of the build — such as removing seam and join lines, skipping steps x and y in the instructions, and the masking and painting. I also store away photos of the original subject for reference later, such as for wiring looms, brake lines, and colour schemes.

What are the biggest challenges of adding aftermarket detail to kitsets?

Not overdoing it — that’s the main thing.

What areas of a kitset do you focus on adding detail to the most?

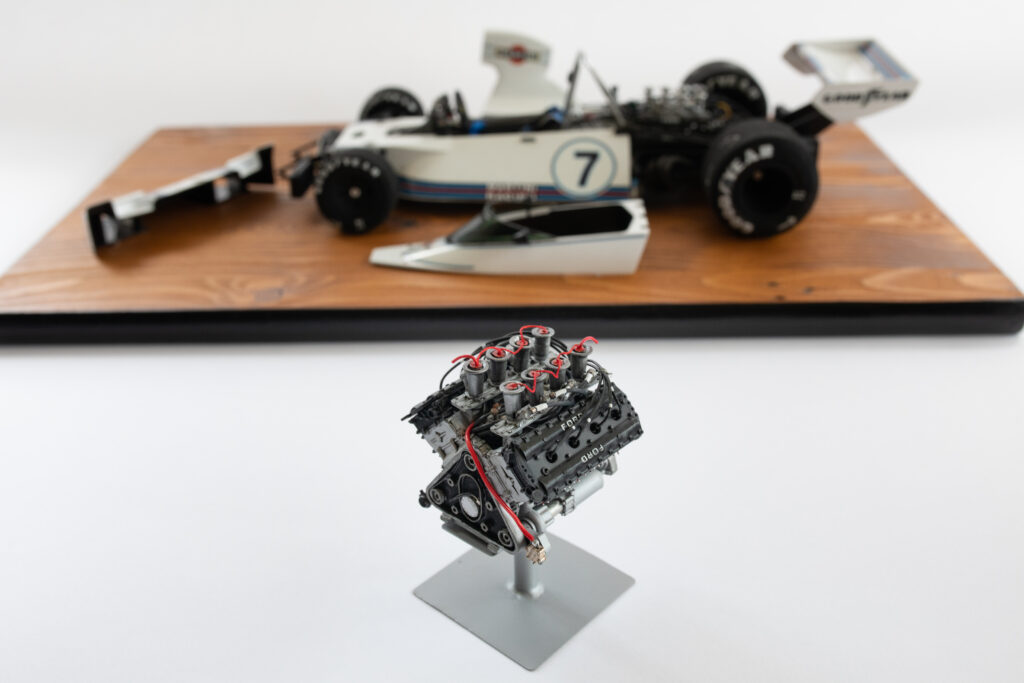

No single component of the car is my favourite to detail, but I do specifically enjoy the finer details of the engine and doing things like throttle cables and the oil and cooling systems.

How do you create and handle such intricate details?

I live with a big magnifying glass in front of me, different-sized tweezers, and a good stash of whiskey to calm the nerves.

Do you simply add the detail or do you have to modify the base kit to be able to include all the extra detail?

Modifying the base kit is often required. Major Japanese vendors provide excellent and accurate base kits, but miss a lot of the mounts and finer details. You often need to reconstruct or adjust components to hold things like struts and allow for things to open as they should. It’s all part of modelling.

Do you scratch build many components, or are most purchased as aftermarket items?

Scratch building is something I love to do. Brass, solder, and styrene are my favourite materials to work with — i.e. the seat belts of the Brabham BT44b are all scratch built from brass, styrene, and ribbon from Spotlight. Craft shops are a great source of materials for scratch-building componentry. However the availability of aftermarket components, such as turned metal rims and photo-etch details, is very handy.

I also like to work with brass and make oil tanks from brass sheets, which are then soldered together and painted for inclusion into the engine bay. It is a very versatile and easy metal to work with, and gives a true ‘metal’ look to the kitset.

What detail do you typically find left out of base kits by the manufacturers that you then have to add?

Usually a lot of the wiring is left out of the base kitsets, as well as oil cans and plumbing for coolants and other fluid reservoirs.

What do you pay for a base kit and then all the details on top?

A larger scale 1:12 base kit would usually cost around $300. If you wish to add all the additional detail you can spend anything from $200 up to $800 for the top-of-the-line detail kits that are available from Top Studio and Model Factory Hiro. The great thing about a lot of the detail components is you can choose either a little or a lot, so if you wish to focus on just the cockpit you can just buy that stuff without needing to spend crazy money.

How does the paint process work for your models?

The models get the same process for paint as a 1:1 car. The bodywork is first filled and sanded from any injection pin imperfection. Once it is perfectly smooth, it gets a layer of primer. After that, the bodywork can get anything up to four coats of paint to ensure depth of colour and coverage. After the paint has cured, any decal transfer markings that need to go on are added. A clear coat is put over top to seal everything in. On the classic kitsets, I then add a wax rub over the top to dull back the shine a little, just as the cars were in period.

You’ve built some iconic F1 machines; what is your ultimate car and driver combo kitset to super detail?

I’m fortunate enough to have one of the two dream cars to build — being a Senna fan, it’s the big 1:12 McLaren MP4/6. I’m considering the super-detail options for it at the moment before committing to the build. The other would be the classic Ferrari D50 of Fangio or 801 of Luigi Musso by Model Factory Hiro — beautiful cars of an amazing era of racing.

It is hard to fully understand the time, patience, and nerve-racking moments that go into a super-detailed work of art. However, hearing people utter “Where do you put the keys in to start it?”, and watching their eyes bulge as they carefully inspect the finished product, shows that all the hours spent in the spare room looking through the magnifying glass were well spent. These kitsets may have started out as a mere humble model, but they have ended up as true scale works of automotive art.