The Triumph Stag celebrated its 50th birthday back in 2020.

Our feature car shows the excellence the design might have achieved had British Leyland given it half the care and attention Dunedin couple Glynn and Alison Gaston put into this restoration

By Quinton Taylor

Photography: Quinton Taylor, [Ground-Sky Photography (Dunlop Targa NZ),] Glynn Gaston, New Zealand Classic Car archives, Stag Owners Club New Zealand

In 1964, Michelotti asked Triumph for a pre-production Mark 2 2000 sedan he could use as a basis for a styling special for the 1966 Turin Motor Show. His effort never made the show because Triumph’s director of engineering and development, Harry Webster, was so pleased with the eye-catching design he took the prototype straight home, keen to evaluate it for production. Buoyed by the sales success of its sports cars in the US market, Triumph expected a warm welcome for a new upmarket design. It saw the Stag as a potential competitor for the top convertible models from Mercedes-Benz and Alfa Romeo. The Stag — at least early on, before it got other nicknames — was sometimes referred to as ‘The Midlands Mercedes’.

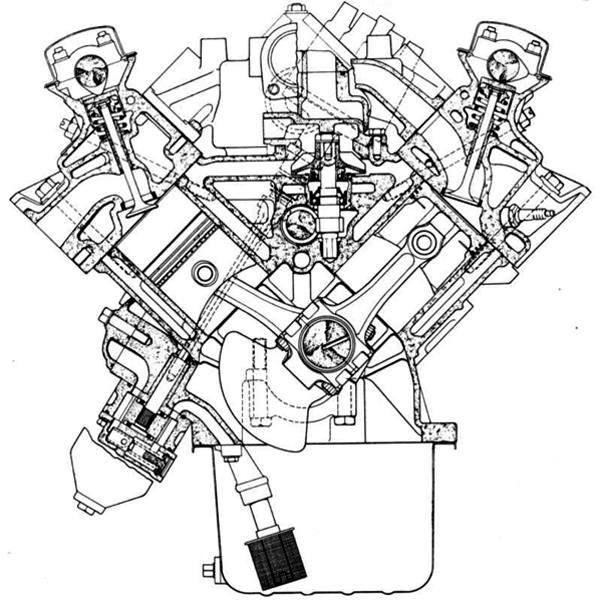

Not helping its protracted development was the transfer of Webster to Austin-Morris with Rover’s Spen King coming on board to manage the project. Early prototypes used Triumph’s 2.5-litre saloon’s driveline then later a new fuel-injected V8 engine intended for a new range of Triumph 3000 saloons. The new motor, designed by Lewis Dawtrey, had a capacity of 2.5 litres and was fuel injected. Leyland opposed the new V8 and pushed for Rover’s new alloy Buick-sourced 3.5-litre V8 to be used.

Leyland actually had an excess of V8 engines. Following the merger with Jaguar in 1966 it acquired Daimler’s 2.5- and 4.5-litre Turner V8s and various experimental Jaguar military V8s from the 1950s, alongside Rover’s all-alloy V8. It didn’t need another. However, Triumph questioned Rover’s capacity to supply its own needs and Stag production. It also knew Rover was tinkering with a new mid-engine two-door design that would use the V8. Meanwhile Leyland boss, Lord Stokes, had cancelled the Daimler engines, citing excessive production costs.

So the Stag engine went ahead and developed a woeful reputation because of a couple of faults that could have been easily rectified with proper development. These were an oil gallery prone to blocking, which caused wear in the single row timing chain, and some poor quality alloy cylinder head casting, even though the engine was basically two Dolomite engines wedged together and they had proved robust enough.

Even more issues

Further problems included inadequately sized main bearings and drive-gears to the water pump shearing. The pump was driven by skew gears on a jackshaft high in the middle of the V of the engine, which also drove the oil pump and distributor. To make matters worse — that it is to say catastrophic — the filler was below the top of the engine, so if it overheated the system was often under-filled, starving the pump of water and leading to a terminal meltdown.

Launched in 1970, Triumph’s new Stag was well received but it wasn’t long before these issues began to impact on its reputation, and the expected 12,000 units a year never eventuated. This led to the Stag’s other nickname, ‘The Triumph Snag’.

A signature of the Stag’s design was its T-roof bar, which added bracing for the bodywork and roll-over protection for the occupants — a handy feature as US legislation swerved to safety consciousness. Initially made detachable, it was soon a fixture. It still allowed soft-top and open-roof motoring following removal of the heavy hardtop. King also had the wheelbase shortened by six inches (152mm). Triumph’s bothersome mechanical fuel was withdrawn and replaced with dual Zenith-Stromberg carburettors. It produced less torque with this arrangement so the engine was bored well oversquare to 2997cc. The bodies were built at Speke in Liverpool for final assembly in Canley, Coventry. This didn’t help shortcomings in assembly quality but it was the engine issues that most hurt the company’s flagship, and they were not swiftly addressed as they should have been as management was focused on getting the government bailout it received in 1974.

A happy ending

When production ceased in 1977, just 25,939 Stags had been built. Without the finance to develop the engine, production of the Stag had to cease and this handsome car quickly achieved almost cult-like status. Where Leyland failed, a band of diehard enthusiasts such as UK engineer Tony Hart succeeded in mending the Stag’s broken heart. Tony formed a British Stag Owners Club in 1979, with associated clubs worldwide. Hart Racing also showed the little V8 was quite a performer in its racing class. Hart’s severely modified Stag proved competitive on UK motor racing tracks. He was convinced the Stag engine was basically a strong unit but it was “intolerant of sloppy workmanship and lack of maintenance”. Now with a new owner, his car still competes in classic motor racing events and has recently been fully restored. A point Stag owners are keen to make is that almost half of all Stags ever built are still on the road.

Last chance saloon

The Triumph Stag pictured here has been lovingly restored from what was once, in the owner’s words, “a horrible, terrible job”. Owners Glynn and Alison Gaston hail from Dunedin and along with their grandchildren now enjoy cruising in the Stag after a three-and-a-half-year restoration.

In 2011, Glynn was looking for a classic car to restore. After 21 years with Air New Zealand he was working as a Super Shuttle driver, with four days on and four days off, which gave him the time to take on such a project — something he had always wanted to do.

“I’d looked at quite a few cars over the years. The idea was to restore a car as something to keep me going. I had looked at different MGs and I would have quite liked an Austin Healey or something similar but they were really expensive.

“Then I saw a Stag and I thought, Ah, this is nice. This is what I would like. So I looked at different ones for about two years, I suppose, and then this one came up in Taupo. I had a friend of a friend pop around and have a look at it for me. He said it was pretty rough and needed a lot of work done to it but it appeared to be quite straight and didn’t seem to have much rust. ‘Right,’ I said. ‘I’ll take it’, so that was that.”

First registered in March 1974, this Triumph Stag Mark 1 model was actually built in 1973. Its previous owner, the fourth, bought the car in 1981. Being close to the Mark 2 version, he found it had a number of Mark 2 fittings, something Triumph did to save costs. That owner had the car for 24 years, leaving it to his son in 2009. The son finally decided it was too much work to restore it and put it up for sale.

“There was quite a bit of interest but people saw it and decided it was too much work,” says Glynn.

Glynn fetched the Stag home on 19 April 2011. It’s fair to say his first sighting of it gave him a bit of a shock.

“I got a transporter for it from Taupo to Picton and my brother-in-law and I took a trailer to Picton. When we arrived it was sitting on a pallet in the Picton yard. It was originally white and somebody had painted it silver! It was horrible; a terrible job! I don’t think they even scraped back the white paint or anything; they just sprayed silver over it. It was disgusting,” he laughs — now.

The tyres were flat, the brakes were seized, and it couldn’t be moved. The transport yard operator came to the rescue with a forklift and the Stag was unceremoniously forked onto the trailer. The pair then headed back to Alison’s sister’s place in Blenheim to show off Glynn’s purchase, albeit with mixed feelings.

“Ali took a look at it and said it was pretty much what she expected for the price. Then she says to me that I am not to work on it all the time. ‘Oh no, I won’t do that’, I said. ‘Hell no!’ For my entire four days off for the next three and a half years, I worked on that car. I wasn’t terribly popular there for a wee while but at least it was all done at home.”

Ringing in his ears

In May 2011, with a reminder from Alison not to spend too many nights in the garage still ringing in his ears, Glynn set about stripping the Stag. He reckons the worst job was jacking up the car, crawling underneath with a water blaster, and removing the thick black underseal. A plus was that the underside of the Stag was almost rust-free. It was cleaned and prepped and a fresh coat of underseal was applied. After stripping the interior trim Glynn removed the wiring loom, which was mostly complete.

“I pulled the wiring harness out and some of the wires were not very good. The ballast resistor they have on those things had overheated and had melted a lot of the wires so I ripped all that out and put an external ballast resistor in — a lot better that way.”

The old coil-type relays were replaced with electronic ones. Relays were added to the headlights to save costly electrical shorts, and that avoided having to run full power through the steering column switches. Glynn chose LED bulbs for the tail lights.

The rest of the body was in pretty good shape with little rust. The bottoms of both doors were rusted out, however, and new sections were welded in. There was also some rust in the rear of the left front mudguard, which was cut out and new metal welded in.

Up front the reconditioned brake cylinders were hooked up with new stainless steel braided hoses. The master cylinder was reconditioned with a new stainless steel liner. New disc brake rotors were fitted. The steering rack received new rubber gaiters, seals, and tie-rod ends before being painted.

The suspension, both front and rear, was dismantled.The front suspension was stripped and the struts overhauled. The bushes were replaced with a polyurethane Flo-Flex bush kit along with new outer ball joints. All the bushes in the rear suspension were replaced with Nolathane bushes, new shock absorbers were fitted, and all the components were cleaned. The entire suspension was then repainted and fitted back in the car.

The time had come to get the rolling chassis off to the painters, so in July 2011 a set of original Stag alloy wheels was found and reconditioned then fitted with 205/70–14 tyres. The car was consigned to Carroll Auto, where the body was stripped, sandblasted, and primed for that gleaming red exterior.

“Harry Williams took care of the body preparation. It was stripped back to bare metal and rust killer was applied on the body and in all the seams. It then received coats of etch primer and spray putty. Then came the two-pot undercoat, two-pot topcoat done with four coats of colour, and then five coats of clear. Harry had the car for about six months and he did a great job.”

Glynn originally chose British Racing Green but then decided it was going to look much better in factory Pimento Red along with the contrasting bling stripes that adorned most Stags. It was January 2012 when the Stag body arrived back at Glynn’s home — but what a transformation.

Beta chairs

Glynn is no big fan of vinyl upholstery so he was reluctant to retrim his precious Stag in the sticky stuff.

“I always felt that for a classy car in its day, a few things let it down,” he explains. “[Vinyl’s] not very comfortable when it gets hot in summer and you stick to it. Besides, I didn’t think vinyl fitted with the quality of the Stag and I wasn’t happy with the seats. They are a bit short in the squab and there’s not a lot of back support as they are quite short.”

By chance, he was talking to a friend who was modifying a Lancia Beta for the racetrack.

“I bought the front leather seats as they were no longer required, and I had the rear seats recovered in some brown leather. The front seats now look much better. They are very comfortable with better support and they make all the difference,” Glynn says.

The front seats are now noticeably larger and better side bolstered than the originals. The rear seats were recovered by Dunedin Auto Trimmers to match the front seats. There are many areas usually covered with vinyl inside the Stag and Glynn himself recovered them all in brown leather, including the overhead T-bar, B-pillars, convertible hood cover, centre console, and even the sun visors. He has also covered the dashboard top panel in stitched black leather. The new dashboard facia panels are an eye-catcher. Gone is the light-coloured plain wood veneer seen in most Triumphs. In its place is something much more substantial and weather resistant, and the grain and colour really make a statement.

“I like to see good woodgrain and the original looked like plywood,” reasons Glynn. “I thought about using mahogany, but when I saw this wood I knew it was the one to use. It has such a lovely grain. It’s African rosewood. I used 10 coats of marine polyurethane and I did it all in the lounge at home. I was not too popular with Ali for doing that. Stunk the house out.”

The dashboard instruments went to Scotty’s Auto Electrics and Speedos at Green Island and came back as good as new, along with a remade speedometer drive cable. New carpets and a new wood-rimmed steering wheel were finished off a very attractive interior.

The Hart of the matter

While the body was being painted Glynn tackled the Stag’s running gear. Armed with a Triumph workshop manual, factory parts manual and even a set of Mettler balance scales borrowed from a friend — who used them for reloading shotgun cartridges — he was ready for the task. It was immediately obvious that the Stag’s V8 engine had been subjected to some poor machining. Glynn schooled up on all the possible problems and spoke to Stag Owners Club members for advice about it. He also sought help from the acknowledged Stag engine guru, UK engineer and racing driver, Tony Hart.

“The engine had absolutely had it. There were birds’ nests in it and hay all over it. You could just see an engine under that but that was about it. Tony was extremely knowledgeable. I took the engine out and stripped it right down and measured it out. It had been reconditioned before because I found it was fitted with ²⁰/₁₀₀₀ of an inch oversize pistons, but it was not a good job. The bores were completely out of round.”

Tony Hart had cautioned that these engines did not respond well to ‘sloppy workmanship’.

“I decided we had to start this thing from scratch. The other thing with these engines was that the original crankshafts were only hardened down to 20 thou, so if you have the crank journals machined round and you get near 20 thou, you are going to go right through the case hardening.”

Glynn had basically determined to blueprint the engine — hence the scales — and a lot of thought and work went into the rebuild before he sent all the bits up to Heat Treatments in Auckland to have the crankshaft nitride hardened.

“I heard from [Heat Treatments] that there was a guy at Taylor Automotive in Auckland who used to be the Stag specialist in New Zealand so I decided to get the crankshaft around there. I had measured it all up and they said I would need 30 or 40 thou undersize for the main bearings and 20 thou under for the big end bearings.”

Meanwhile, work continued on other engine parts. Glynn weighed the conrods and pistons, and, in accordance with Tony’s instructions, machined the like parts to within one gram of each other. The engine took quite a while to finish, with bits scattered all over the country. While sourcing new parts Glynn made some enlightening discoveries.

“I thought I would stick with genuine old English County pistons. They duly arrived and on the box it said ‘Made in Israel’. The Vandervell bearings stated ‘Made in Germany’. Nothing is what it seems,” he laughs.

In the course of the rebuild, Glynn added a cure for the Stag’s famous timing chain issues.

“The timing chain tensioner on the original motors had an oil pinhole at the back that would block. It needed clean oil or it jammed and let the chain go loose, which then jumped a tooth, meaning valves hitting pistons, or it broke altogether. The new tensioner I fitted from Germany is spring-loaded.”

The Stag’s engine block is chromium steel topped by two alloy cylinder heads with a single overhead camshaft per bank. Cleaning and machining work for the block and cylinder heads was completed by Rodney Smith of Rod’s Engine Services in South Dunedin. Correct measurement for the cylinder head is critical on these engines for longevity and Glynn got them exactly right.

“The heads were good, with a little bit of corrosion, but they had replaced the original ones and these were fitted with hardened valve seats. The original heads were sitting inside the car. I took the heads out to Rod and we replaced the valve seats anyway even though they had been done. Most of the valves were pretty good but we changed a few them. All new valve springs were fitted and Rod line-bored the camshaft bushes and put new bushes in.”

Everything was then balanced, including a new clutch, and Glynn started the task of reassembling the engine and gearbox. A Lumenition electronic ignition kit was added to the distributor along with an external ballast resistor to improve starting and keep everything reliable. A new alternator was fitted, as was a new reduction gear starter motor, water pump, and oil pump. Both carburettors were reconditioned and powder-coated, along with many new linkages and pipes.

Going into overdrive

The gearbox was dismantled and all synchros, bearings, and seals were replaced. Glynn’s car was originally fitted with a standard four-speed manual gearbox. He purchased, cleaned, and reconditioned an overdrive unit, which meant changing and upgrading a few parts in his gearbox to fit it. Unable to find a replacement rear gearbox/overdrive mount, he made one and fitted new rubber bushes.

To cure the Stag’s reputation for overheating, a new modern radiator was fitted along with a Toyota water header tank, which has a low water level warning light fitted in the dashboard. A Kenlowe electric fan, an auto thermos switch, and a cabin bypass switch also help prevent any sign of the Stag’s Achilles heel.

By September 2014 Glynn was able to see his very detailed restoration nearing completion. It was only a matter of giving everything a final clean, adding all fluids, and a few pats for luck. Would it start?

“She went first pop,” says a delighted and relieved Glynn. “I balanced the carburettors and adjusted the mixture. I was told those Strombergs don’t keep their tune but that’s not true. Mine are still good after 10,000km, which is all the car has done since it was finished.”

A quick run out to Taieri Airport confirmed that Glynn made the right call when he decided that if he was going to restore the Stag then it had to be done right.

“I think my Stag is now putting out a lot more than the 140bhp they were supposed to when new. It was quite a quick run out the back of the airport and it ran beautifully. There was an amazing difference in the ride quality, too. It is very much better.”

It was just a few days before the annual hospice charity car run in 2015 and Ali had entered the Stag.

“It wasn’t finished so I had to really put in an effort but we made it,” Glynn tells us.

Well worthwhile, too, as the Stag wowed the hospice rally judges, who hailed it as the best British Car. In 2017 the Gastons took the Stag to the Roxburgh Classic Car Show, where it won best overall classic. Later that year, the Stag won the best Triumph award at the Best of British Car Show in Dunedin. In 2018 I had to judge the Best British Classic category at the Dunedin Autospectacular where Ross Osborne’s newly restored MGC GT just pipped the Stag for the top spot.

“We haven’t been on many long runs with the Stag — just a few local ones. I intend to fix that next Easter when we will take it up to the car and air show at Omaka,” Glynn mentions.

Glynn enjoyed great support from Alison and his sons during the restoration, although Alison did get concerned for his health. “I remember he spent a whole winter working under that car on the ground,” she says.

There’s no doubt Glynn’s Stag is an eye-opener. I first saw it at the Dunedin Autospectacular a couple of years ago; its bright red paint, set off with sparkling chrome, beamed under a sunny Dunedin winter sky. I was delighted to see it felt as good as it looked.

It’s time for a drive — with the soft top down of course. It’s a nice place to sit, especially with Glynn’s upgrades to the interior. It’s an easy starter and once warmed up this willing little V8 provides plenty of poke accompanied by a healthy V8 burble. It’s just noisy enough to be fun. The list of improvements are almost all things Leyland should have done for this car to achieve its full potential. It rides beautifully on its tautened suspension, and even six years after being restored it is as tight as a drum.

Glynn says fitting the T-bar into the body was quite a difficult job and admits he needed some extra mechanical assistance. However, it stiffens the car enormously, and that togetherness makes it noticeably better than other roadsters of the era. The result is nary a rattle or squeak over some of Dunedin’s less forgiving bitumen. The Stag offers a very enjoyable ride, somewhere between executive express and sports car. Glynn has constructed a classic that has risen far above the reputation it earned in the 1970s when it succumbed to Leyland’s lack of development. Glynn summed up what he learned during the restoration he was determined to get right.

“It takes time, it really does. If you want to do it properly then you have got to do the work on it. Check with the experts and people who know the car to do it right.”

STAG POINTERS

An enduring classic: The Stag was produced in Mark 1 and Mark 2 models. It’s not uncommon to find some Mark 2 components in late Mark 1s. Many were supplied with a BorgWarner (BW) 35 automatic gearbox or a BW65 in late-production models. The four-speed manual gearbox and the optional overdrive provide more driving enjoyment. Later models used a slightly thinner sheet steel in the bodywork so check for rust.

In New Zealand, the Stag Owners Club (SOC) is one of the largest one-model clubs in the country with around 120 active members. Club members have discovered a number of tweaks and parts from other makes that keep the cars on the road at a considerable cost saving. Joining a club such as the SOC or the Triumph Register is a source of helpful advice and essential parts supply.

Market Values: Prices are steadily increasing. A good Stag is still a relatively cheap entry into the classic motoring world, especially if it has been sorted with life-saving upgrades and all the correct bits. Prices for tidy ones in New Zealand start at around $20,000. In 2016 Webb’s auctions sold a 1975 model in white for $39,100 on an auction estimate of $23,000–$26,000. Top-condition models are clearly heading to the $40,000 mark.

A movie star: Bond swapped the Aston for a Stag in Diamonds Are Forever (1970) and a Stag also appeared in significant roles in Straw Dogs (1971), Dad Savage (1977), Second Sight BBC 2000–01, New Tricks BBC (1974), Car SOS (2013), For the Love of Cars (2014), and High-Rise (2015).

A lot of Michelotti: From the 1950s, Michelotti had contributed distinctive and successful designs such as the Vanguard 6 and, under the Triumph brand, the Herald and 1300/Toledo/Dolomite models, but hit his straps with TR4/TR5/TR6, the Spitfire, the GT6, the Triumph 2000, and the Stag as well as other cars in the Leyland stable. His studio also produced around 1200 cars for other marques — everything from tourers to town cars plus trucks and buses for Ferrari, Maserati, Hino, Daihatsu, BMW, DAF/Volvo, Renault, and Renault Alpine to name a few. He was apparently quite fond of a bus design he did for Leyland.

TRIUMPH STAG SPECIFICATIONS

Manufactured: Mark 1 models up to 1973 then Mark 2 until 1977

Production: Speke and Canley, factories, UK: 25,939 (19,097 UK and 6,780 exported)

Engine: 2997cc, steel block, 90-degree V8, alloy cylinder heads with single overhead camshafts per head and two valves per cylinder, five main bearings

Bore & Stroke: 3.385in (86mm) x 2.539in (64.5mm)

Horsepower: 145bhp (108kW) @ 5500rpm

Torque: 170 Ib·ft (230Nm) @ 3500rpm

Transmission: Triumph four-speed all-synchromesh manual; optional: BorgWarner 35 (BW 65 in last versions) automatic; Laycock de Normanville overdrive, Type J on manual gearboxes and operating on third and fourth gears

Clutch: Laycock diaphragm-type single plate 9in (22.86cm) hydraulic operation

Suspension: Front: independent McPherson struts with coil springs and telescopic damper units; single lower transverse links with fore and aft location radius rods, rubber bushed pivot, ball-joint swivels, and anti-roll bar; rear: semi-trailing arms, independent suspension mounted on rubber insulated steel frame and coil springs

Steering: Rack & pinion power-assisted steering, turning circle 10.4m

Wheels: Standard size, steel 14in 5J rims with stainless steel Rostyle type trims, optional GKN Kent, five-spoke alloy rims or 48-spoke wire wheels with centre-lock hubs with 185HR14 radial tyres

Brakes: Front: 10⁷/₈ths (270mm) disc brakes; rear: 9in (228.6mm) drum brakes

Wheelbase: 8ft 4in (2540mm)

Track: Front: 4ft 4¹/₂in (1330mm); rear: 4ft 4⁷/₈ths (1342)

Overall length: 14ft 5³/₄in (4420mm)

Width: 5ft 3¹/₂in (1612mm)

Height: With soft-op erected 4ft 1¹/₂in (1258mm)

Weight: 27cwt (1375kg)

Performance: 0–60mph (0–100kph approx.) 9.5secs; 0–100mph (162kph) 29secs; standing quarter-mile: 17.1secs (manual) 18.2secs (automatic)

Maximum speed approx. 118mph (190kph); varied, with some cars achieving close to 210kph

Fuel consumption: 13.7lt /100km, 63-litre fuel tank