data-animation-override>

“An extremely rare Bugatti finds a new home in New Zealand where it will be the subject of a total rebuild”

Generally speaking, Bugattis are a rare and elusive breed on New Zealand shores, with perhaps the most famous being the ex-Ron Roycroft Type 35. However, another Bugatti has joined the handful that reside here, and New Zealand Classic Car magazine was among the invited guests who braved a chilly Waikato evening to witness this special car’s unveiling at Hamilton’s Classics Museum earlier this month.

Purchased by the museum’s owner Tom Andrews, this Type 57 Bugatti carries with it an extremely interesting history — and it’s scheduled to enjoy an equally interesting future.

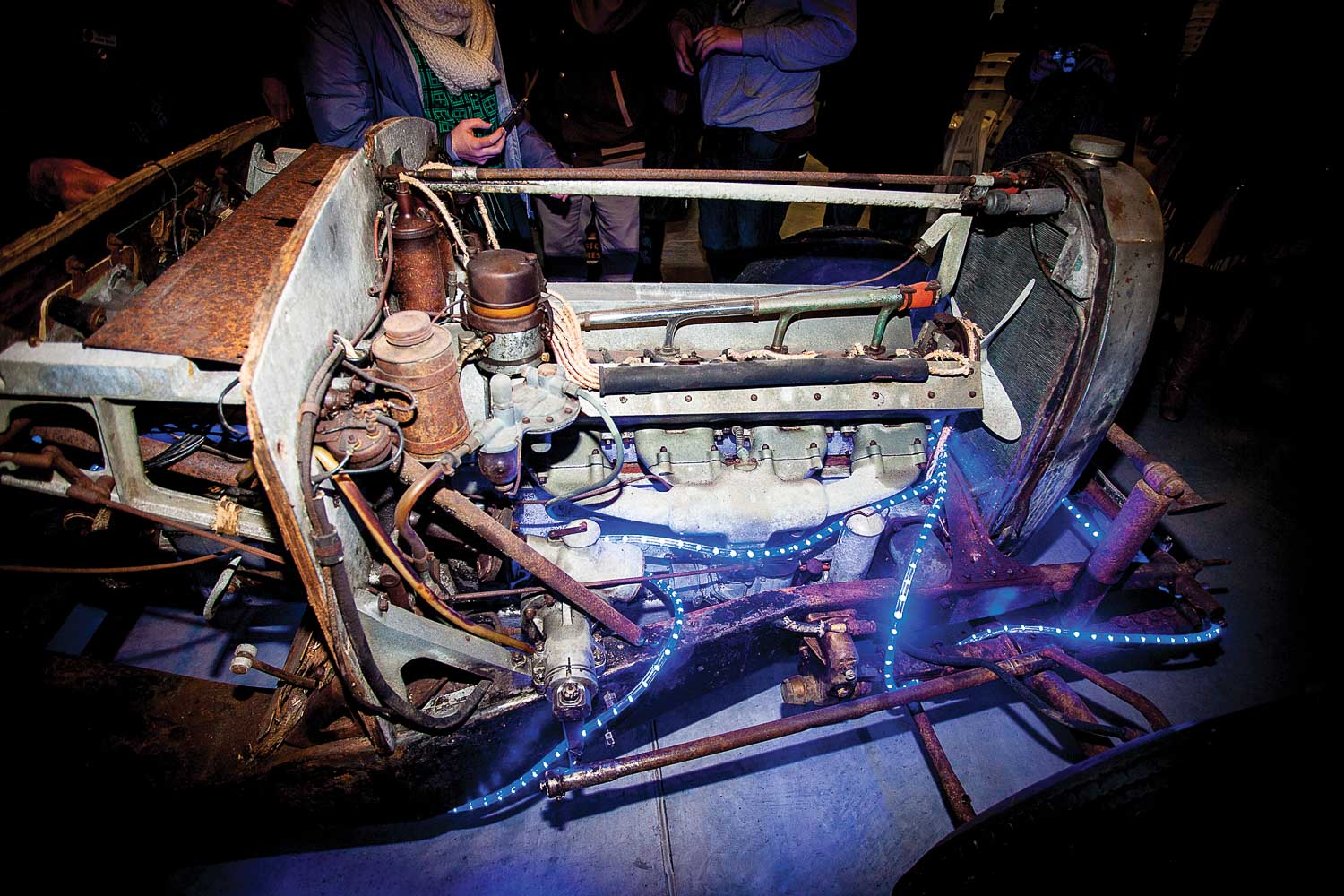

Ultimate barn find

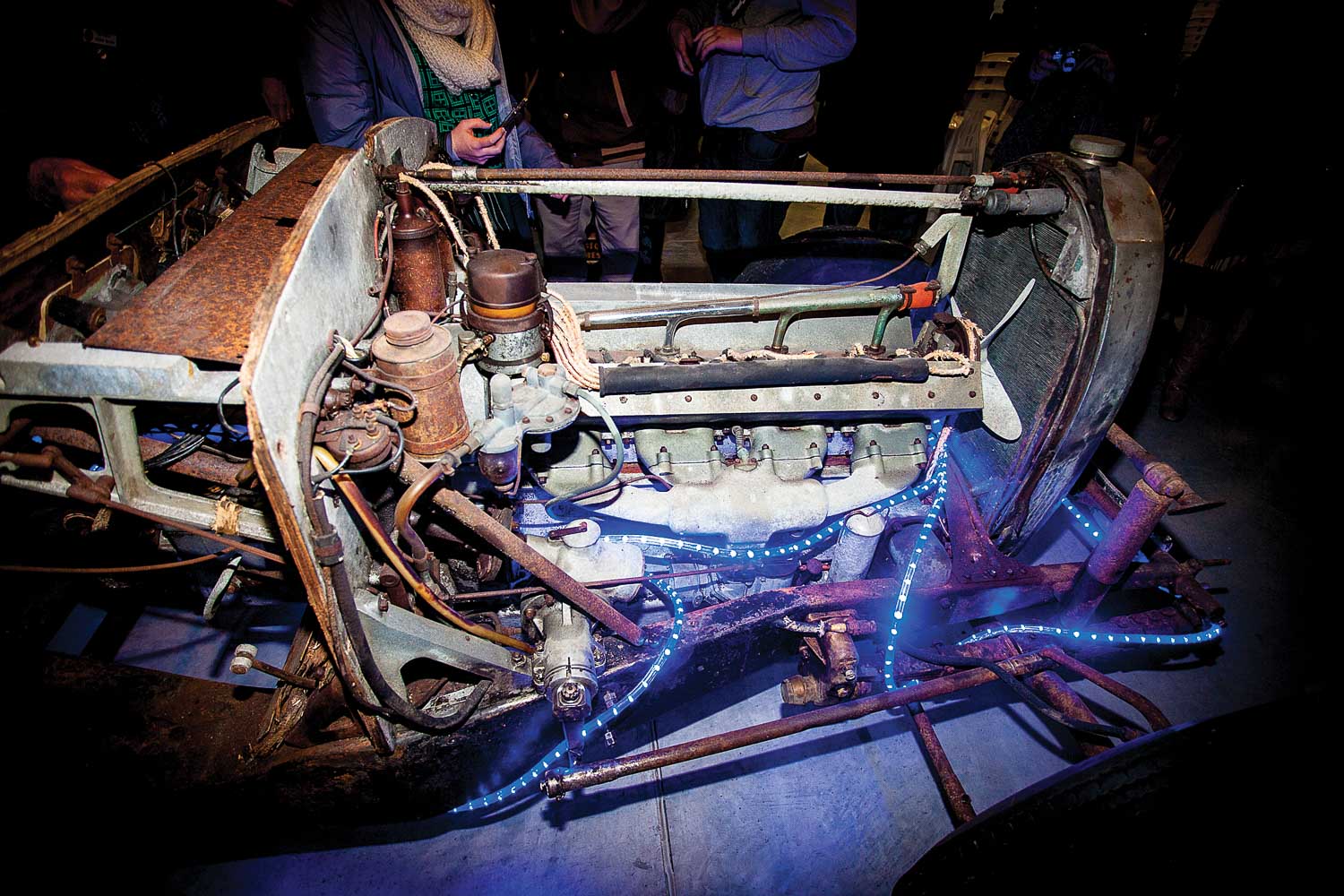

This particular Type 57 — one of only 719 ever built by Bugatti — was discovered in December 2014 in western France as part of The Baillon Collection, one of the largest barn-find treasure troves in recent history.

This collection of cars was gathered by Roger Baillon over a period of several decades, which saved a large number of them from being scrapped. Alas, when his transport company faltered in the ’70s he sold around half of his collection, keeping the remaining cars at his property in Western France, untended, for the next 50 years — many of them exposed to the elements. Baillon died more than 10 years ago, while his son Jacques, who inherited the collection, died last year.

In late December 2014, France’s Artcurial Auction House announced its sale of the Baillon cars. The 60 vehicles recovered from the various barns and sheds that housed the collection eventually fetched a total of US$28.5 million (just shy of NZ$42 million) at auction — some US$10 million higher than the auctioneer’s initial estimate.

The chassis of this car is No. 57579 with motor, gearbox and differential numbered 417 — this confirming that the car originally carried a Gangloff body.

For several years Tom has thought of owning a Bugatti, and following the announcement of the Baillon auction, he had a friend from England travelled to France to give a report on this car, and several of the others in the Artcurial Auction. At this point he knew that the Bugatti’s Gangloff body had been removed and a Ventoux body was on the chassis, and he understood that this Ventoux body had been made on July 5, 1938 — body number 86 — and came from chassis No. 57706. A full investigation of the car was carried out to leave no doubt of its identity, Tom acquired the Type 57 for NZ$489,260, and it subsequently made the long trip to New Zealand.

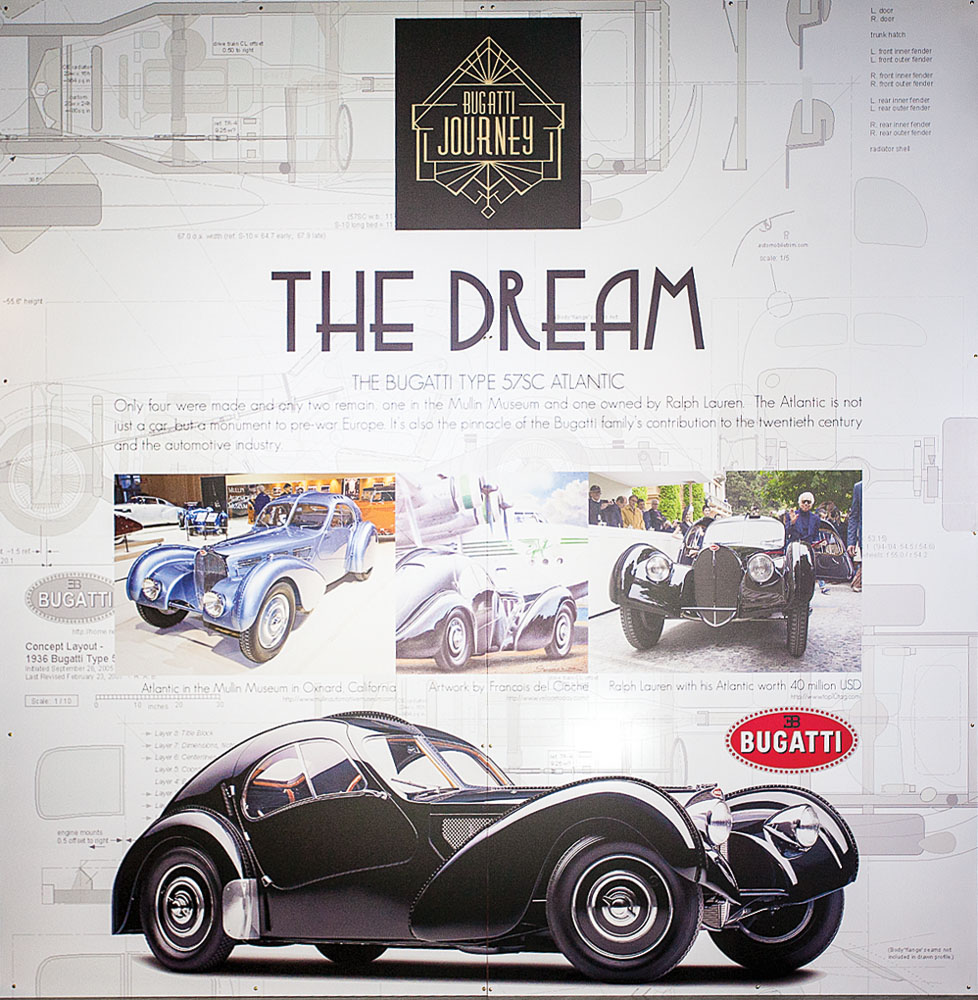

While the car was revealed to the public in its as-found and rather sorry-looking state, this Bugatti is set to undergo a remarkable transformation. Tom’s short-term goal is to rebuild the Type 57 as a Ventoux-bodied car, but for the long term he has more intriguing plans which involve eventually rebuilding it as a Bugatti Atlantic, one of the rarest, most sought-after cars ever made.

With only four examples ever produced, the Bugatti Atlantic is an automotive holy grail for many, as evidenced by Ralph Lauren’s stunning, award-winning, black Type 57SC Atlantic — a car that was sold for US$40 million (NZ$58.4M) in 2010. The notion of a fifth Atlantic rising from the ashes of this Type 57 and finding its home in New Zealand is exciting, to say the least.

But for now, Tom’s Type 57 will be rebuilt in Ventoux form — and we’ll be following this one with plenty of interest.

The Bugatti Type 57

Although designed and built as a road car, racing variations of the 57, the so-called ‘Tank’ Bugattis, actually won Le Mans in 1937 and 1939 — proof that, as far as Bugatti was concerned, the distinction between road-going and race cars was never clear. The typically elegant Bugatti chassis was powered by Bugatti’s gorgeous straight eight — a work of art in itself — with a capacity of 3257cc, and initial power output was quoted at 104kW (140bhp), later rising to 130kW (175bhp) Supercharged variants of this engine produced around 149kW (200bhp).

It was destined to become Bugatti’s best-selling model, and many Type 57s were bodied by outside coachbuilders, although the factory offered no less than five standard bodies — all of them designed by Jean Bugatti — the Stelvio convertible, the four-door Galibier, the two-door Ventoux, the Atlante two-seater and, finally, the truly iconic fastback Atlantic.

Originally introduced in 1934, the sportier and more powerful 57S appeared the following year, while the fitment of a Roots supercharger became an option in 1937 for both the 57 and 57S — hence the birth of the 57C and 57 SC, with the ‘C’ standing for Compresseur. The S versions of the car were discontinued in 1938, and the 57 and 57C continued in production until the advent of World War II — a few examples were also built post war.

Fitted with streamlined bodywork, the 57 was also successful on the race track. These special 57s scored historic victories at the 1936 French Grand Prix and, as previously mentioned, at Le Mans.

Ironically, the man behind the design of the Type 57, Jean Bugatti, would lose his life at the wheel of the 1939 Le Mans-winning Tank in August of that same year.

The Bugatti Atlantic

The Atlantic was based on the Jean Bugatti–designed Aérolithe concept car of 1935. As with Bugatti’s GP car of that same era — the Type 59 — the Aérolithe featured a body constructed from magnesium alloy panels. These panels could not be fitted together with conventional welding, instead being riveted together — this leading to the car’s distinctive dorsal seam.

However, when Bugatti came to building the four Atantic coupés — the first of which was put together with parts from the Aérolithe show car — it utilized aluminium alloy for the cars’ panels, although the concept car’s dorsal seam was retained.

The Atlantic’s swooping lines and curves live on as an exemplary example of 1930s design and engineering — indeed, the Atlantic is not just a car but rather represents a glorious moment in pre-war European history, and stands at the pinnacle of the Bugatti family’s outstanding contribution to the 20th century and the automotive industry.

This article was originally published in New Zealand Classic Car Issue No. 296. You can purchase a print copy or a digital copy of the magazine below: