The Auckland Mustang Owners Club bolted off with the top two prizes at the 2020 Intermarque Concours d’Elegance, winning both the team prize and individual prizes at the Ellerslie Classic Car Show. The teams win made them the host club of the 50th anniversary show in February 2021. Here’s Classic Car’s story on the winning Masters Class car, and here is the story on the winning Teams Event cars.

By Ashley Webb, photography by Strong Style Photo

When Ford unveiled the ground-breaking Mustang in 1964 it set a precedent by creating a new class of sports car, which met with immediate success and unparalleled sales across the US. Yet the recipe was quite simple: take an existing rear-wheel-drive chassis, such as the Falcon; design and build a sporty 2+2 coupé body for it; drop an inline-six or V8 engine under the bonnet; and, as they say, the rest is history.

Surprisingly, for an American car the Mustang drove reasonably well, and looked even better. However, Ford’s rivals weren’t about to let it bask alone in the sunlight for long. While it may have invented the ‘pony car’, Ford soon had a few rivals in the corral.

The folks over at General Motors (GM) struck back first with the Chevrolet Camaro, and then went one better by introducing the track-capable high-performance Z28. Not only did the Camaro go head-to-head with the Ford Mustang on the street and in showrooms, it also competed successfully in the Trans-Am Series, winning the championship in 1968. Ford’s president, Semon ‘Bunkie’ Knudsen, watched Camaro Z28 sales climb from 602 in 1967 to 7199 in 1968, the additional exposure of the model in Trans-Am racing rubbing off on the rest of the Camaro line-up.

As the ’60s wound to an end there was only one thing left for Ford to do — hit back strong and hard. The uppercut came in the form of the 1969–1970 Boss 302.

A NEW BOSS

The first Boss 302 rolled off Ford’s Dearborn assembly line on 17 April 1969, just 14 months after Bunkie Knudsen took over the reins at Ford Motor Company, and only seven months after the initial stirrings of a special high-performance Mustang programme. Our featured Boss left Dearborn on April 30, 1969.

Finally, Ford could sell what it raced, and compete against the fast-selling Z28 on the street and on the racetrack. By the end of 1969, some 1628 Boss 302s had been built — easily enough to satisfy Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) homologation regulations.

The name ‘Boss 302’ was curious. The man credited with the car’s creation, Larry Shinoda, formerly of GM, was once asked about the project he was working on. As a quick response and in order to keep what he was doing under wraps he simply said, “I’m just working on the boss’s car.” The name stuck and the Boss 302 was born, having been created for a very specific mission: to be the boss on the racetrack.

ALL-OUT PERFORMANCE

To comply with SCCA racing-league rules, participating auto manufacturers had to sell a production version of any car entered in the Trans-Am Series. After losing the 1968 season to the more powerful Chevrolet Camaro, Ford was determined not to be outdone again. Ford’s Mustang engineers — appropriately enough — were spurred into action, designing and building an all-out-performance production Mustang.

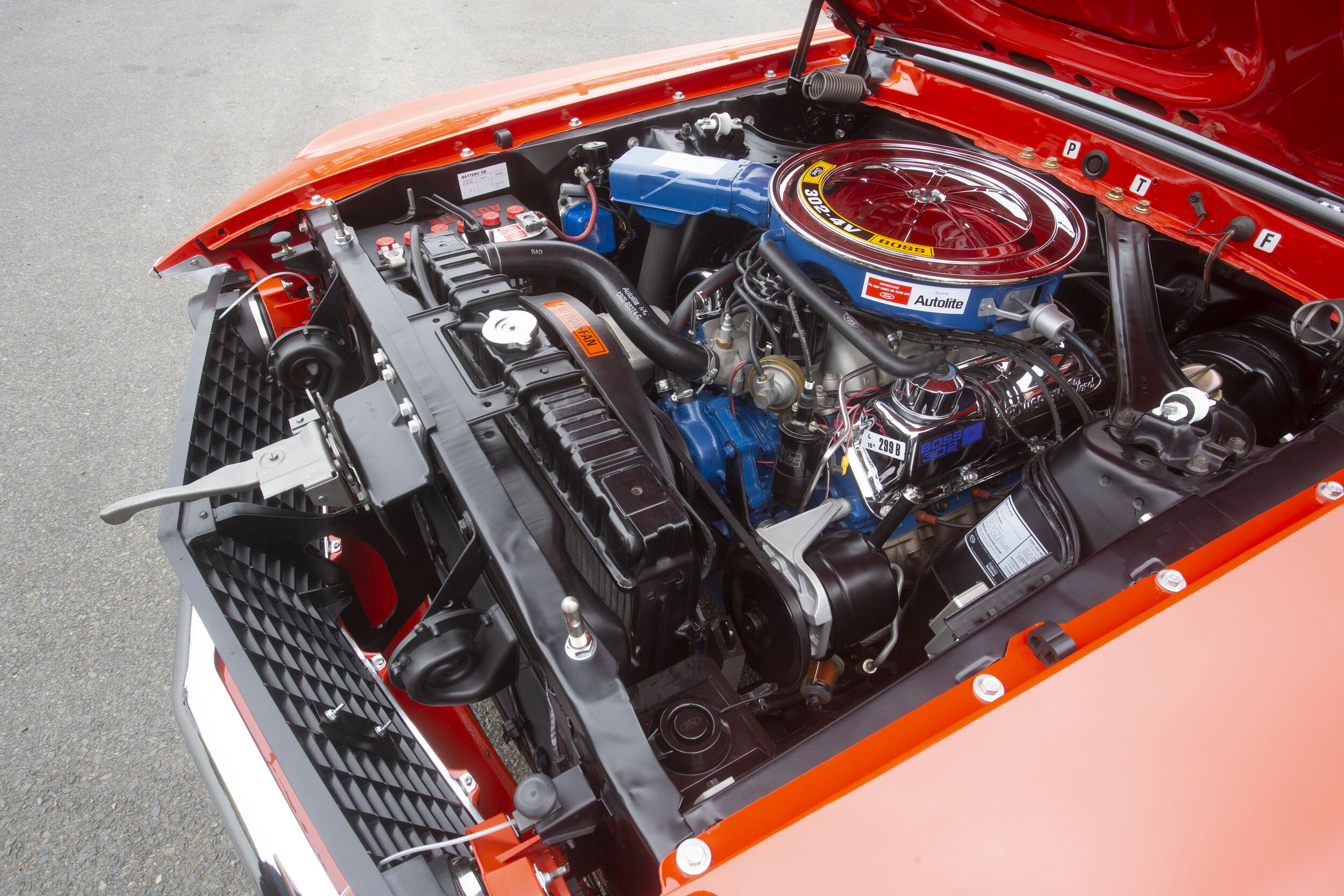

For starters, if Ford was set on regaining the Trans-Am Series title, it needed a competitive engine. The company’s previous attempt at building a high-performance motor, the Tunnel Port Windsor V8, had resulted in that disastrous 1968 racing year. As it happened, Ford engineers had also experimented to successfully combine a Windsor block with Cleveland heads, ending up with the 4.9-litre (302-cubic-inch) engine that eventually powered the Mustang, and Parnelli Jones, to victory in the 1970 Trans-Am Series.

While the Windsor-Cleveland combination proved strong and powerful, there was a lot more to producing a successful production racing engine than grabbing bits from different parts bins. After recognizing the Cleveland head’s racing potential Ford’s engineers designed an improved intake-port design that gave the air–fuel mixture a straighter shot at the cylinders. Angling the valves also provided much-needed space for the big 56.6mm (2.23-inch) intake and 43.6mm (1.72-inch) exhaust valves.

However, while this combination may have worked well on the track, it was not necessarily ideal for street use. In 1970, the intake valves were slightly reduced in size to 55.6mm diameter to allow increased low-end torque (in theory) for slightly quicker initial acceleration, while the exhaust valves remained the same. These heads also featured steel spring seats, adjustable rocker arms, screw-in rocker studs, and pushrod guide plates.

Other technical details included a unique mechanical cam with a high-lift design and a forged-steel crankshaft, balanced both statically and dynamically. All this mechanical rotating mass was fed copious amounts of fuel through a massive Holley carburettor breathing through a purpose-built aluminium intake manifold.

To vent the exhaust gases efficiently, new cast-iron exhaust manifolds were designed specifically for the Boss 302. The gases were then fed into a transverse muffler system (for 1969 only), which helped give the Boss its unique and revered exhaust note. The result was a dedicated sports car with all the credentials to go Trans-Am racing. Few creature comforts or options were included as standard on the initial 1969 Boss 302 — this car had one purpose: to make it around a Trans-Am racetrack faster than any other.

COMPETITION READY

Back in the late 1960s, US-based insurance companies were quick to pounce on any car with even the smallest performance aspirations, so it wasn’t uncommon for manufacturers to fudge their engine-performance data. Officially, the production Boss 302 produced 290bhp (216kW) at 5800rpm but its track-going counterparts evidently produced as much as 470bhp (350kW).

As far as transmissions were concerned, with this much power on tap, the only option was a four-on-the-floor Toploader gearbox with a Hurst T-handle shifter for swapping cogs. The gearbox could be ordered in either close-ratio or wide-ratio configuration, both of which delivered power to one of four rear ends — A-code (open) 3.50:1; S-code (Traction-Lok — Ford’s official name for its limited-slip differential [LSD]) 3.50:1; V-code (Traction-Lok) 3.91:1; and W-code (Detroit no-spin) 4.30:1.

However, the Boss 302 wasn’t just about dropping a race-bred high-performance V8 between the shock towers of a road-going ’69 fastback Mustang. The 302 engine demanded serious respect, so modifications to the suspension set-up were introduced, including heavy-duty front coils, tube shocks, and rear leaf springs to cope with racetrack loadings.

To control wheel hop, which limits a car’s ability to get the power down and thus speed off the line, staggered heavy-duty Gabriel rear shocks were used.

The competition-style suspension also saw the addition of a 0.85-inch (21.5mm) rear anti-roll bar, tucked in-between the fuel tank and rear axle housing. A quick-ratio steering box with a 16:1 gear ratio was also part of the standard package, and if you wanted power-assisted steering then you simply ticked the relevant box on the options list.

With the Boss 302 engine and other necessary upgrades, the Mustang 302 was finally ready to compete.

Sadly, in August 1970 Ford quietly discontinued the Boss 302, and in November that same year announced that it was withdrawing from motor racing altogether. To meet the demands of the time, due to an increase in foreign-import car sales, Ford was forced to design, build, and market the Maverick and Pinto compact cars, which stole both time and money from the company’s racing budget.

Yet, as the street version slipped away, the Boss 302 Trans-Am race cars were heavily embroiled in battle on the circuit. With George Follmer finishing second place at Donnybrook on 5 July 1970, Mustang had held a 22-point margin over the Camaro midway through the series. The street cars may have gone but on the track the Boss 302 track cars were just hitting their stride.

1969 FORD MUSTANG BOSS 302

Engine: Ford V8

Capacity: 4942cc

Valves: Two per cylinder

Bore/Stroke: 101.6mm/76.2mm

Compression: 10.5:1

Fuel system: Four-barrel Holley 780cfm

Max. power: 290bhp (216kW) at 5800rpm

Max. torque: 393Nm at 4300rpm

Transmission: Four-speed manual Toploader

Suspension F/R: Upper arms, strut-stabilized lower arms, heavy-duty coil springs, anti-sway bar / Live axle, heavy-duty leaf springs, anti-sway bar, staggered Gabriel shock absorbers

Brakes, F/R: Power-assisted disc / Drum

Steering: Recirculating-ball, quick-ratio (16:1) manual steering (power steering optional)

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 2743mm

Length: 4663mm

Track F/R: 1486/1486mm

Width: 1811mm

Height: 1250mm

Weight: 1550kg

PERFORMANCE

Max. speed: 121mph (195kph)

0–62mph (0–100kph): Six seconds

Standing quarter-mile: 14.5 seconds

ENCORE

The 1970s saw a sorry state of affairs for American muscle. A lost decade of performance machines meant that Ford had little else to offer but its Cobra II and King Cobra Mustangs. With a miserly two-barrel carburettor version of the 302-cubic-inch (5.0-litre) as the top performance option, there wasn’t a lot of muscle flexing going on behind those fancy decals.

Performance enthusiasts turned their backs on new cars during the ’70s, and focused their attention on previously owned Boss 302s and other ’60s muscle cars. These gas guzzlers were absolute bargains at a time when fuel prices had been driven out of control in the aftermath of the 1973 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) oil embargo.

Wanting to evoke past glories, Ford considered resurrecting the Boss name on a few occasions for the retro-styled 1994–2004 Mustang. The Mach 1 programme was also reconsidered for the Boss name in 2001 and again in 2003 but, after much discussion, the idea was eventually shelved.

The legendary name finally returned to the streets in the form of the track-oriented Boss 302 that was unveiled at the Rolex Historic Races at Laguna Seca in 2012. This was another true track car for the street. According to Ford it was the quickest, best-handling production Mustang it had ever offered.

Ford stayed true to its word by keeping the free-flowing, high-revving 5.0-litre V8 engine au naturel in the Boss. This V8 screamer featured a revised plenum–velocity stack combination, camshafts with a more aggressive grind, and cylinder heads that had been treated to CNC-machined ports and chambers for better airflow across the entire rev range.

The 2013 Ford Mustang Boss 302 has the highest-tech suspension system of any non-SVT factory Mustang, with the most-powerful naturally aspirated (NA) V8 that Ford has ever packed under a bonnet. Changes were few for the 2013 Boss 302 but why mess with the best Mustang ever built?

Now the bad news: the 2013 Ford Mustang Boss 302 was to be the final year for this incredible package. When Ford introduced the modern Boss for the 2012 model year, the company stated that it would run for only two years, so sadly, the Boss name has gone once again.

LEGEND

The Ford Mustang is probably the most successful and respected American sports car of all time. The legendary 1969–’70 Boss 302s have stood the test of time as an example of the best engineering and design the US had to offer at the time. Few cars with a short two-year production span have left such a mark on the performance-car landscape.

As for the 2012–’13 reincarnation of the Boss, it’s hard to imagine Ford will ever produce another dedicated, high-performance road/track machine — or one wearing the Boss 302 name for that matter — that’s aimed fairly and squarely at the hardcore enthusiast market.

Mind you, we hope we’re wrong!

BLUE OVAL

As a youngster growing up in Tauranga Paul Hildebrand was no stranger to Bay Park Raceway. During the late ’60s he would often accompany his older brother to witness some of the great motor racing clashes of the era between the likes of Dennis Marwood, Grahame McRae, Graeme Lawrence, and Jim Richards, to name a few. One of Paul’s favourite cars was the PDL Mustang that made its debut in late 1970 driven by Paul Fahey.

By the time Paul was in his mid teens he was a self-confessed blue oval fan and went on to own several Fords, including Escorts, Cortinas, Capris, and Zephyrs.

“I spent all my hard-earned appren-ticeship wages on modifying my cars on such things as mid-wheels, twin-carbs, and anything else that would make them perform better,” he said.

Once Paul became a married family man, cars became much less of a priority. After spending five years in London, Paul and his wife decided to bring back a BMW 325i, which proved a worthwhile exercise. Selling it gave him enough for a deposit on their first house. Paul never forgot those early years at Bay Park with his older brother — or, in particular, the PDL Mustang.

THE SEARCH

About 12 years ago, with his family grown up, Paul decided to begin the search for a Boss 302 Mustang. He found a 1968 Shelby GT350 in Las Vegas on Ebay and after getting a spotter to check it out, Paul decided to buy it and shipped it back to New Zealand. About a year leter the same spotter located a 1969 Boss 302. The car had already been completely stripped down and primer coated. The body was reported to be in relatively good condition and, according to the owner, all the parts were included with the car. Based on this information Paul bought the car in late 2009.

Upon the car’s arrival in New Zealand, Paul contacted Steve Sankey from C.A.R.S. in Pukekohe. Paul had been impressed with many of Steve’s restorations and decided he was the right person for the job, with one proviso: that Steve was the only person to work on the car.

The first task for Paul and Steve was to identify all the parts, label them correctly, and determine what was missing. Armed with a parts catalogue Steve was then able to begin ordering the missing parts.

ROAD TO MASTERS

After fully inspecting the car Steve said it had been stripped and blasted except for the suspension components and there was surface rust all over the body, with some more serious issues on the underside.

The restoration began with Steve cleaning out the internal side of the rear chassis rails before replacing the boot floor. New rear quarter panels were welded into place, along with a complete new floor section. Rust repairs were also made to the lower firewall area, torque boxes, and upper radiator support panels. Steve unstitched the entire roof skin and repaired the internal structure before welding the roof skin back into place. The body was then placed onto a rotisserie and blasted back to bare steel. The underside was sealed and then finished in the original spec red oxide. The paint was colour matched to a sample found in the transmission tunnel.

By this time the factory differential and rear and front suspension had been completely refurbished and detailed to original factory spec before being reinstalled in the car. The brakes were reconditioned and new brake lines added.

The next step was to refit and perfectly gap all the original panels on the car before it went off to the painters to receive its original Calypso Coral colour.

Paul at Marsh Motorsport rebuilt the motor, while the original Toploader manual gearbox was reconditioned in Pukekohe by Derek Price.

With the mechanicals taken care of, Steve turned his attention to the interior. The original seat frames were stripped apart and repainted before being re-cushioned and re-recovered in factory correct black upholstery. The same applied to the rear seat, with a new headlining — factory correct of course — as well as new carpets.

Steve continued his efforts to keep the car original as possible by retaining the original door cards, wiring loom, dash components, steering column, headlights, and tail lights — with the exception of new lenses. The finishing touch was the fitment of new Magnum 500 wheels and tyres.

One of this country’s finest Mustang restorations was completed in late 2019, requiring only final detailing in preparation for the Masters Class competition at the 2020 New Zealand Classic Car Magazine Ellerslie Classic Car Show. This year’s competition for the highly coveted award was the tightest it’s been for many years. When the judges’ sheets had been collated and tallied, just two points separated first and second place and only eight points separated second and third.

With an impressive winning total of 548 points out of a possible 590, it’s fair to say that this Boss’s first big day out was definitely a success.