There’s something about the rattle of an air-cooled VW engine that evokes freedom in all three of the radically different vehicles it powered

By Ian Parkes

The classic Type 1 Beetle was designed to be the norm — the people’s car — but as it soldiered on, almost oblivious to rivals’ increases in performance, handling, space, comfort and equipment, it became a rallying point of car counterculture, acquiring a timeless appeal.

The Herbie movies may have boosted its popularity in the US, where its contrast to mainstream vehicles was most marked, but around the world the car’s singular appeal produced a steady stream of buyers. Factories in Mexico and Brazil continued to churn them out with production in Brazil continuing until 1996, and the last of the original Beetles were produced in Puebla, Mexico, in July 2003. Toyota may claim to have sold more Corollas but those were really different cars that just happened to share the same name. The Beetle is the undisputed best-selling production car in both numbers made (21.5 million), and longevity (65 years).

Then there’s the Type 2 VW, another smash hit, AKA the Kombi, which also struck a similarly timeless chord with free-spirited, free-thinking and free-ranging adventurers.

Buggy time

Which brings us to the Beach Buggy. While many other vehicles served as platforms for beach bashing, the Beach Buggy, designed by Bruce Meyers in 1964, crystallised the form, once again based on the cheap and cheerful VW platform.

The little bug-eyed beast with its curved bonnet, flared guards, swoopy body and high tail was undeniably cute. It spawned a huge demand, a beach culture boom, an iconic desert race (the Baja 1000), and thousands of copies around the world, with a following as loyal as those attached to the Beetle and the Kombi.

Meyers didn’t claim to invent the Beach Buggy, or Dune Buggy as it’s known in the US. Throughout the ’50s people had cut away car bodies to fit larger wheels and reduce weight to bash through the dunes.

“They had a motor and transmission mounted right up to the rear axle,” Meyers told Top Gear in 2013. “At the end of each axle, they had two, sometimes three, wheels welded together, and the frame rails went out 20 feet to the fronts. They spat flames and were a lot of fun, but I knew they were inefficient.”

Bruce Meyer, Mr Mayers

Then Meyers, a surfboard maker and boat builder, spotted someone tearing around the sand in a light and short VW chassis. Designed and built by Hilder “Tiny” Thompson in about 1960, the alloy-bodied Burro was a refinement of Pete Beiring’s original homebuilt effort, based on a wrecked Beetle’s chassis. The Burro wasn’t pretty, but it was selling.

“It skimmed around like a mosquito across water, even with 35bhp and four-inch tyres. All the weight over the rear end made a lot of sense in the desert,” Meyers said. “It was why the Mexicans drove around with 50-gallon drums of water in the back of their pickups — the driven wheels got the best chance of traction, because they’re getting pushed down and onto the loose surface.

“Then there’s the trailing arm suspension. That’s why these things skip across the dirt. And the whole VW set-up — engine, mechanicals — got me thinking. I could build something really innovative. But I had no idea it’d be responsible for the Baja 1000 …”

Form and function

EMPI was already offering kits to bolt onto scrapped Beetle chassis but the Sportsters were angular and steel, as appealing as beach furniture piled up by a hurricane. Meyers, used to crafting fibreglass, got to work with his pen and called his cheeky and stubby design the Manx, after the short-tailed cat.

“I’m an artist and I wanted to bring a sense of movement and gesture to the Manx,” he told Top Gear. “Dune buggies have a message: fun. They’re playful to drive and should look like it. Nothing did at the time. So I looked at it and took care of the knowns. The top of the front fenders had to be flat to hold a couple of beers, the sides had to come up high enough to keep the mud and sand out of your eyes, it had to be compatible with Beetle mechanicals, and you had to be able to build it yourself. Then I added all the line and feminine form and Mickey Mouse adventure I could.”

EMPI Sportster

EMPI Sportster

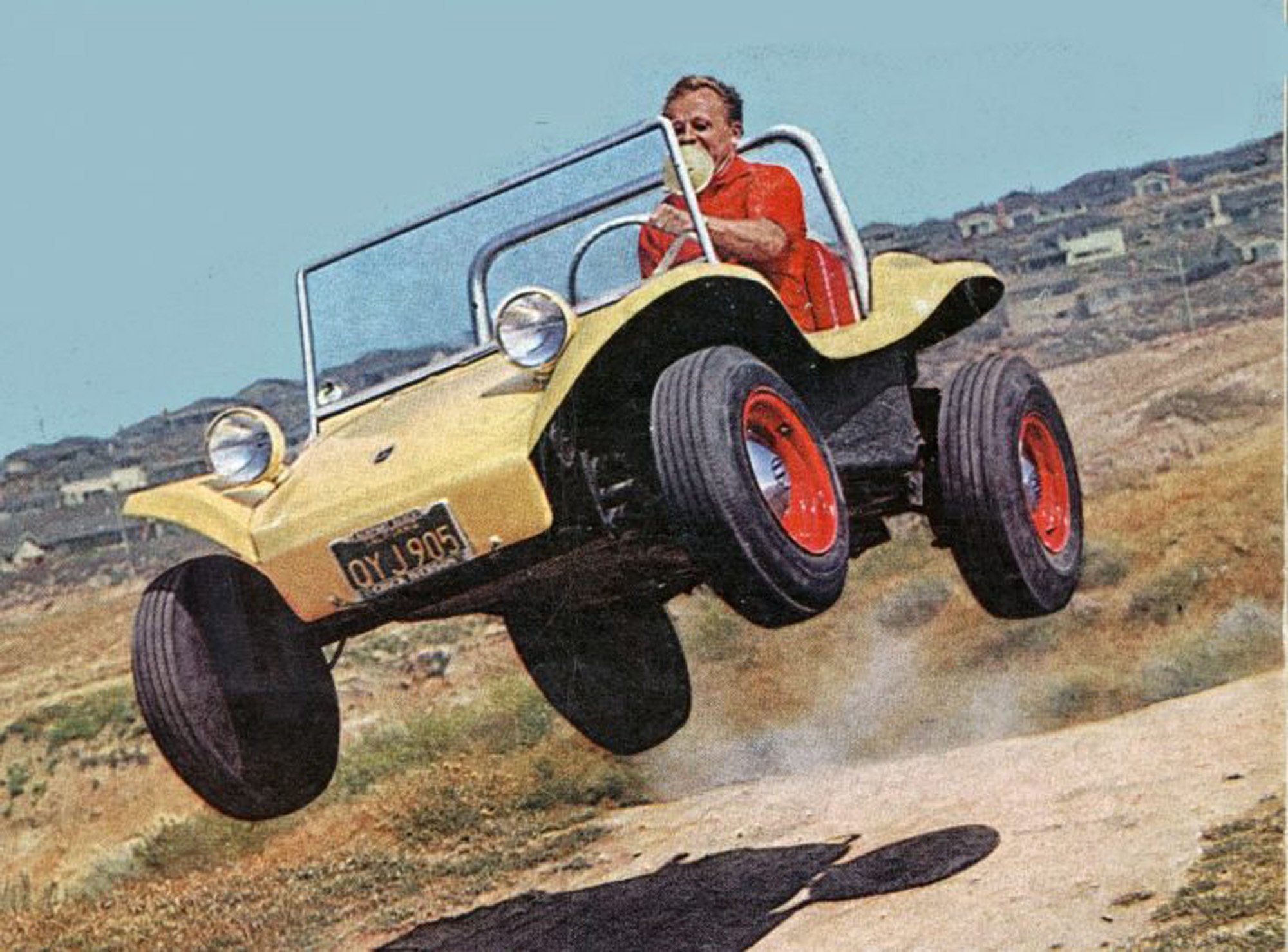

Bruce Meyers proves the Manx’s strength

His first 12 monocoque bodies were super tough and only needed the VW engine transmission and suspension bolting to them, but they were tricky to make and demand was surging. He redesigned the body for a shortened VW floorpan, putting him on his way to churning out 5280 Manx kits and hundreds of Manx IIs. Soon the design was being copied or cloned around the world.

Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway drove a Dune Buggy in the 1968 movie The Thomas Crown Affair. Elvis Presley got in on the act in Live a Little, Love a Little from the same year, and in Watch Out, We’re Mad (1974), a red Dune Buggy, driven by Terence Hill and Bud Spencer, stole the show.

The Manx body was all too easy to copy and tweak. The internet forum Dune Buggy Archives has catalogued more than 225 body styles. Volkswagen reckons that more than 300 companies worldwide have copied the Meyer Manx Dune Buggy, and that by the 1980s about 250,000 Beetle-based vehicles had been produced worldwide.

Meyers was just a little late realising what he had started. He lodged a patent in 1965 and in 1969 he sued a company for copyright infringement. The judge ruled against him, saying the Manx had been in the public domain a year before he was awarded his patent. Meyers reckons he could have appealed but it had already cost a fortune “and the other guy had a much meaner lawyer”.

Late 1960s water pumper

Boom and bust

Although 1969 was a boom year for buggy culture, the whole thing skidded to a halt in 1970 when new US vehicle laws banned open wheel arches and exposed engines. Mod kits were hastily designed but the Meyers Manx company went out of business in 1971 because of tax problems and the failed patent case. Some other volume makers also quit but small custom manufacturers have carried the flag for the faithful to this day.

The appeal of the Beach Buggy’s direct line to simple fun is as strong today as it ever was. The president of the Manx Club in the USA, Mike Dario, compares it to the freedom of riding a motorcycle, being able to smell the air and feel the ground beneath your wheels.

“But riding a motorcycle I always felt defensive, I was always looking for the other person to not see me,” he says.

“When I drive the Dune Buggy, everybody looks … people are looking and people are smiling. You smile and wave at somebody driving by and they smile back — the next thing you know, the smile is huge.”

Fiat 600-based buggy

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 373