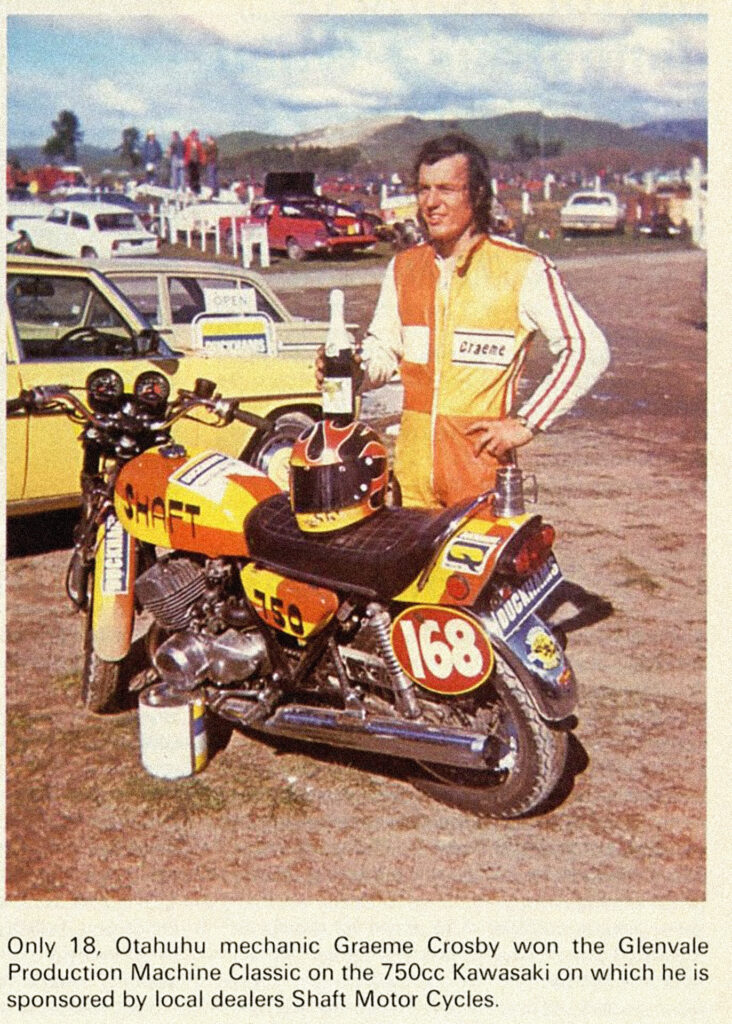

During the COVID lockdown, Michael Clark had to forego lunches with motorsport celebrities but he interviewed motorcycle racer Graeme Crosby on his direct route into the Grand Prix ranks via Zoom.

Graeme Crosby: My first actual race was at Porirua on a circuit set up around the shopping centre. I was riding a little 350cc Kawasaki, an Avenger, which was a little two-stroke 350 rotary valve with something like 10hp. Suddenly, I found myself in third spot and I’m thinking this is actually pretty good. Anyway, I think I got in second spot and we only had a couple of laps to go and I overcooked a corner and ran wide. Health and safety back in those days required you to keep the crowd back, so they got a piece of rope and tied it around a 44-gallon drum, then a 10-metre gap, and another 44-gallon drum, and so on — and I went over the kerb at great speed. I still finished second — with one of those 44-gallon drums following behind in third place. Yeah, it was a bit of an experience.

Graeme went from race to race, with enough encouragement to do the next, and the next …

From my point of view, from the early ’70s I saw two major events that I wanted to do. One of them was the Castrol six-hour race in Australia at Amaroo Park. I’d won the Castrol six-hour race riding by myself and I felt good enough to be able to go and attack this six-hour race in Australia. When we got there we went to see Kawasaki Australia to ask if there was a possibility of getting a bike. I’ll always remember the guy — a big fat bastard he was; he sat behind his desk and said: ‘These bloody Kiwis come over here, mate, and think they can take the rides off us guys. We got far better guys. I suggest you go down to Melbourne and get yourself a bloody old Triumph or something — that’s my advice.’

The dirt and the flies

I didn’t go down and get the Triumph. I got a second-hand Kawasaki that had been almost annihilated — just kind of old shit that had been put together. The six-hour in Australia meant you had to pull the whole bike apart [for scrutineering]. I don’t know if you’ve been to Amaroo Park but it’s just dusty and dirty, so we pulled this bike apart and put it back together. We ran that bike with another guy, I think we finished sixth and we were pretty happy with that result — that was my first first foray into getting out of New Zealand and onto the international circuit.

Michael Clark: So that event in Australia was instrumental in your taking your next step?

GC: Yes; well Ginger Molloy was second in the 500cc world championship in 1970, and one of his mechanics, Ralph Hannan, was working at the time in Australia for his brother Ross Hannan. I was told to go out to Bankstown, or somewhere out west, to meet this guy who was building a Z900. Ross said I could race it. So I went to his guy’s place and banged on the door. He came out — typical Aussie: stubbies on and holes in his T-shirt. Anyway, he dragged me in past his wife, who was making dinner, and there in the lounge was this bike being built on a couple of beer boxes; apparently it had been under construction for about eight months.

Corky, the guy, didn’t think much of me at all. Anyway, they finished the bike and I got in the car with Corky on a Friday night and we drove up to Lakeside [Park] in Brisbane. We pulled this bike out and I did about 10 laps. Suddenly it was like, “Ohh, hang on a second; we need better tyres,” or, “We need to do this or we need to do that,” and he was right behind me so we built this bike and we campaigned that bike all over Australia. I don’t remember ever getting beaten on it, to be fair, so that was the start of the connection between Ross Hannan, Corky the superbike builder, and this Kiwi who just turned up. That was a really, really, really good time in my life.

French flavour

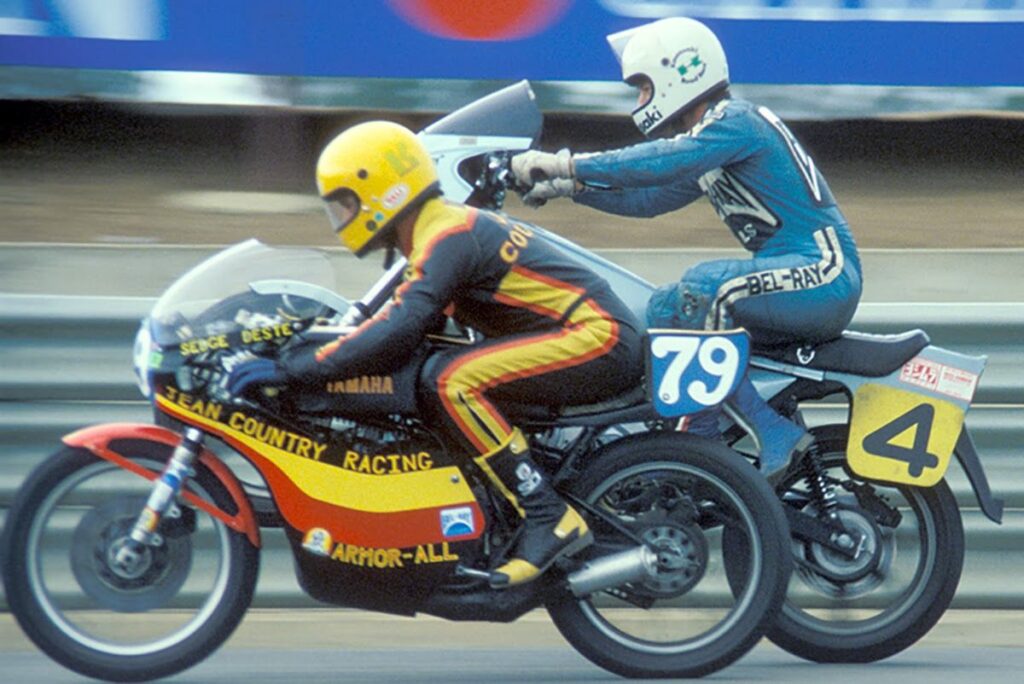

We put one other event together, and that was the Bol d’Or 24-hour race. Two riders, one motorbike, two or three guys, a few air tickets, and away. That was one of the first times I got hooked on international travel. I just loved the idea of going places and the French name I suppose. I Ioved the international flavour.

We had a lot of problems with the bike but eventually we got it going. I recall one incident: the bike was our superbike production bike — high handlebars, a couple of Ciba-Geigy headlights so we could see round corners at night. I got in behind Phil Read on his factory Honda, and I thought, This is me! I’m in France and this is fantastic; the smell of all those sausages burning in the park; man, this is unbelievably good.

Then Phil put the brake on and I forgot to. I whistled up underneath him completely sideways, with the rear brake on, and slid sideways past him. Luckily I didn’t take him out. He turned in under me, and I just turned and gassed it up. The thing kept sliding and I did this big power slide and came out right beside him. I thought, This is good — and then, of course, it gripped and spat me in the air a bit. I didn’t fall off but the next time I came around there was this big black mark with a little bit of an ice cream whip at the end.

A couple of years later Phil said to me, “I always remember that time at Le Mans when you came past me. I’d like to donate 20 pounds so you can buy some clip-ons.” I just said, “I don’t want clip-ons. I just want the 20 pounds.”

I could have done with it, too. That was Phil Read. One of the good memories.

Suzuka eight-hour sensation, 1978

Michael Clark: You’ve got six bikes there that are factory Hondas — there’s no way in the world we can get anywhere close to them.

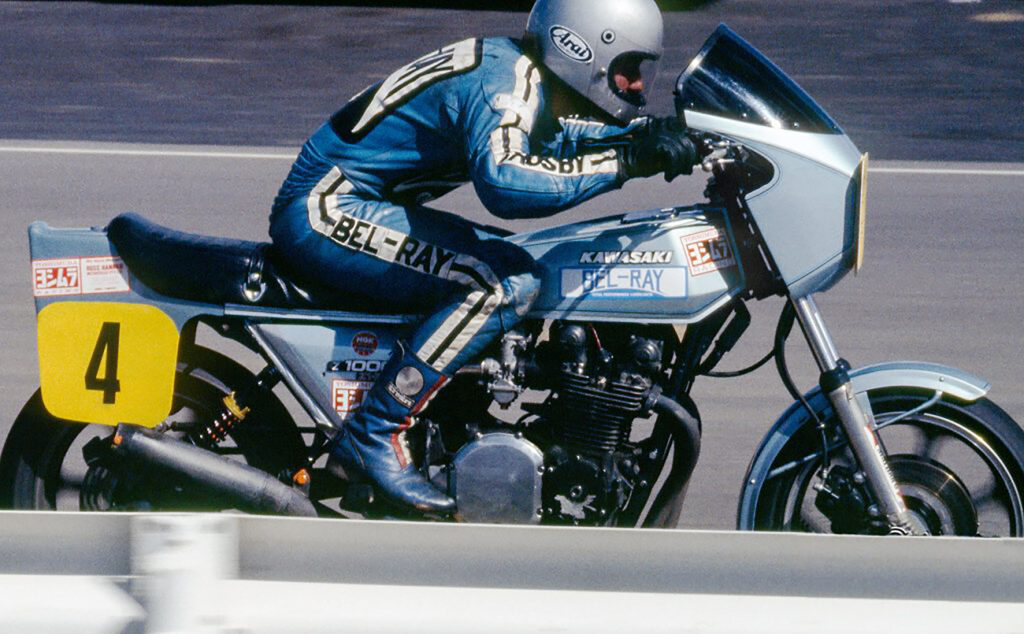

GC: Well, things change, don’t they? I got to Suzuka through the association with Ross Hannan and Yoshimura and I ended up riding for Moriwaki. He built a silhouette bike that looked like a road bike but it was in a different class; when I did some testing, the thing was a missile.

Of course you know you’ve got the Japanese factory right beside the Suzuka circuit. The bike’s been sorted out already, and when you get on the thing and it’s got 145 horsepower you go, “Haw, it’s so easy!” Then you look at your lap times and you’re going quicker than the factory Honda guys, and you start thinking, We could be in for a chance here.

We did some testing on the south course and I ended up breaking the lap record by about three seconds, having fun doing wheelies and just really enjoying it. Honda had sent out some — well, not spies but they were asking who I was. We had them on, saying, “He’s just a New Zealander, one of the riders, but the other rider’s twice as good as him.” So Honda is going “F…! What are we going to do?”

The team finished third, after running out of fuel, but Croz won the race in 1980, for Suzuki.

Isle of Man rookie

Moriwaki built a Formula 1 bike for Graeme’s UK and TT campaign with clip-on handlebars and a fairing but Graeme also wanted the ‘silhouette’ bike, the scourge of the factory teams at Suzuka. He left an indelible impression on the ticket collector at the gate, after asking which way does the track go and what’s the lap record? He turned right, and duly set a new lap record.

GC: We went to Brands Hatch, as a precursor to the TT, and I ran the Formula 1 bike. I actually slipped off it going down Paddock HillBend, which was a pain in the arse, but then I pulled out the Moriwaki superbike and lo and behold I was first or second quickest qualifying for the Formula 1 TT race. So straight away I thought, This is cool; I’ll go out on that. So that is where it all started.

You can imagine — there are 40,000 people at Brands Hatch and some guy comes out on a road bike and he’s beating the likes of Ron Haslam, Mick Grant, and all these guys on these factory bikes. I’ve got the high bars and I’m hooning around and having a ball so suddenly it was like this breath of fresh air on the racing scene.

From there I went to the TT, and of course we went back to the conventional Japanese Formula 1 style of bike and I finished fourth in my first race, which was apparently quite a good effort. From there on in there was quite a lot of interest from virtually everybody because it wasn’t Honda, it wasn’t Kawasaki, it wasn’t Suzuki; it was Moriwaki and this crowd of Antipodeans and Japanese who would sit cross-legged and eat rice out of a tin. I love telling this story because it’s true — nobody had any money.

Michael Clark: I’m really interested in your impressions of the Isle of Man because the Isle of Man mountain circuit is a serious racetrack and you would have gone there knowing what it can do to people, what it had done to people.

GC: You are talking second thoughts, I suppose? Beneath this rough exterior lies a man who is quite concerned about staying alive. I put quite a lot of effort into learning the TT, albeit a different method than most people. If you go to a circuit that’s 60-odd km for one lap and you’ve got to do six laps in a little over two hours, you’ve got to take it seriously. They told me never to try and race the TT; if you treat it as a high-speed ride, then everything sort of falls into place.

Organisers would put racers in a car with someone who knew the circuit. Former TT winner Charlie Williams went through gear changes and revs on his two-stroke, which meant little to Graeme, who introduced a different method, albeit inadvertently.

Learning the hard way

I persevered for a while until we got to a place called Laurel Bank. Basically, it’s a right-hand corner. It’s famous because Tom Phillis got killed here and straight away my eyes spread out and took in every blade of grass there, like an instant picture.

When I said to Charlie that a place looked like a dangerous section, he would say, “Yeah, yeah, somebody hurt himself here”, or “This guy smashed himself up there”. I made a map on which each corner belonged to somebody who had an incident and that’s how I learnt the circuit. When you get to Quarry Bends, you think, Mitsui Itoh — I know the guy, Japanese 50cc racer. He ran off the track there and hit a rock face. Now I know why he’s got a split lip and scars all over him.

Charlie told me that at one particular corner there’s a sort of drop-off and you can catch the kerb. He hit it and broke his foot there. Straight away, you are looking at this corner and thinking Charlie’s foot, so you step out 2mm offline, or probably about 10 feet! All of those things gave me the ability to learn the circuit in a graphic kind of way.

Suzuki Great Britain broke its long partnership with Barry Sheene, took the Kiwi superbike star straight into its 500cc Grand Prix team, and gave him two Formula 1 bikes for the TT world championship, which he won — twice.

I get on this Grand Prix bike, and it’s just so small — 120bhp and weighing 120 kilos. The thing was a missile. It steered exceptionally well, it handled really well, and the suspension and brakes were good. It was a factory bike — the best Suzuki could produce.

I was given the bike on the basis that I’d be riding a road bike around racetracks in the UK. Obviously a lot of people were thinking, Hang on, there’s a hell of a lot of UK riders who are more than capable of having this Grand Prix bike, especially as it’s Suzuki Great Britain, so why have they got a New Zealand rider and an American rider in the UK team? I’d have my interview and then Barry [Sheene] would have his views against it and it would go on and on. We actually used it to create this competition — Johnny-come-lately and the old guy who should have had the ride. Really, when I look back on it, it was a good bit of journalism.

More media attention

Michael Clark: Well, Croz, you wouldn’t have been aware of it because you were in England but in 1981 there was a great deal of excitement in New Zealand because you had put your bike on pole for the British Grand Prix. Unfortunately, you came down — and you took a couple of names with you.

GC: Well, if you are going to do it you might as well do it in style! I was leading the British Grand Prix in ’81 after having pole position and feeling pretty bloody good because Randy was an internal team competitor and I was on pole ahead of him so I had a vested interest in keeping up the speed. I think it was at about lap five or six, I went into a high-speed right-handed corner and I just lost the back end. It wasn’t a highside; it just slipped out. I held onto the handlebars and turned round and of course I’ve got Barry Sheene, Marco Luchinelli, Randy, and Kenny Roberts right in my face, and I’m sliding on my arse. I saw Barry was trying to get on the inside. He pulled the front brake on a bit too hard, lost the front end, and ended up in the hay bales as well. It wasn’t a good start to the British Grand Prix to take out a lot of the contenders, that’s for sure, but as I’m getting myself up this English journalist comes across and thrusts his great big microphone at me, saying, “Graeme Crosby, how does it feel to ruin England’s chances of having Barry Sheene become world champion this year?” We were only only quarter of the way through the season. Man, I was pissed off about that. I should have hit the bugger — but I didn’t.

Michael Clark: I guess in most people’s minds three of the greatest riders of all time have been Agostini, Hailwood, and Valentino Rossi, and then this guy Marquez comes along. I wonder if in 20 or 50 years people are going to think back and say, “My gosh, that was something sensational.”

GC: That’s what makes motorsport so good. You can’t be perfect all the time. You have these guys come up; they rise above everybody; they do the best they can. Then it’s time for somebody else to take the mantle, and that is a perfect example. Rossi and Marquez and Fabio Quartararo might be another one; we just don’t know. You can never compare the old to the new. You can just congratulate them on what they did at the time.

Michael Clark: I couldn’t agree more.