The Lancia Stratos was a design and performance high point for one of Italy’s most innovative and illustrious car brands, but if you want one now, you’d better be prepared to build your own

By Patrick Harlow

On his own, and later with his wife Suzie, Craig Tickle has built and raced many rally cars. Starting in 1988, Craig went half shares in a Mk1 Escort and took it rallying. Apart from a few years in the US studying how to be a nuclear engineer, he has always had a rally car in the garage. When he is not playing with cars, he works as an engineer for his design consulting company.

Naturally, anybody interested in rallying has heard of the Lancia Stratos, the poster child and winner of the World Rally circuit in 1974, ’75, and ’76. Just as the Lamborghini Countach rebranded the world of supercars, so, too, did the Lancia Stratos when it came to getting down and dirty in the rally world. In addition to space on bedroom walls, the two cars shared a birthplace in the Bertone design studios, and both were penned by the great Marcello Gandini.

By the time Craig got into rallying, the sun had already set on the Stratos. It had been pushed out by the internal politics of the Fiat group, which wanted the Fiat 131 Abarth to take its place on the world stage. Fiat knew it could make a lot more money out of selling thousands of 131s than it could from the niche Stratos. Lancia would have to wait for 1982 for its next WRC win.

Stratospheric prices

Politics at Fiat had turned against the car and took it out of the limelight, but that dimmed Craig’s enthusiasm not one iota. In fact, the resultant rarity has only increased the car’s appeal. Lancia was required to make 500 road-legal versions of the car before it could go rallying. These were called the Lancia Stratos HF Stradale. For some reason, Lancia never made the full 500, only managing 492. Still, even if it had made 500, the car’s price was so stratospheric that Craig knew he would never be able to afford one — at least not a real one.

That naturally takes us down the replica or tribute car route. In 1984, a company called Transformer set up shop in England building a Stratos replica. It eventually changed its name to Hawk Cars, and has produced more than 300 rally and road-going examples of the Stratos. More recently, in 2010, another English company, LB Specialist Cars, started doing the same. Hawk makes two models, called the HF2000 and HF3000. LB makes three, all called the STR but for three different engines: the 2.5-litre Alfa V6, the Toyota 3.5-litre V6, and the Ferrari Dino engine.

Craig became aware of the replica market in the early 2000s. Although these were much more affordable, he did not have the spare cash to commit.

To infinity and beyond

That all changed in 2015 when the couple received an inheritance with the condition they did something fun with it. Suzie liked the idea of using the money to purchase a Stratos kit, too, so they began to set the wheels in motion. The LB kit was chosen over the Hawk because with the Hawk you had to buy the whole kit. With LB, Craig could order what he wanted and save money by manufacturing some components himself, using the skills he had picked up building rally cars.

Eventually, an order was placed that would include the chassis to take the 3.5-litre Toyota engine. As with most small companies, the production of the kit does not begin until the deposit has been placed; hence it was no surprise for the couple when they were told it would be a 12-month wait. In fact, it was 34 months before the kit arrived in New Zealand.

One advantage of the long wait for delivery was the intervention of Brexit. The value of the pound dropped and suddenly, for Craig and Suzie, everything was 25 per cent cheaper. Consequently, more components were ordered and it was an almost complete kit that arrived.

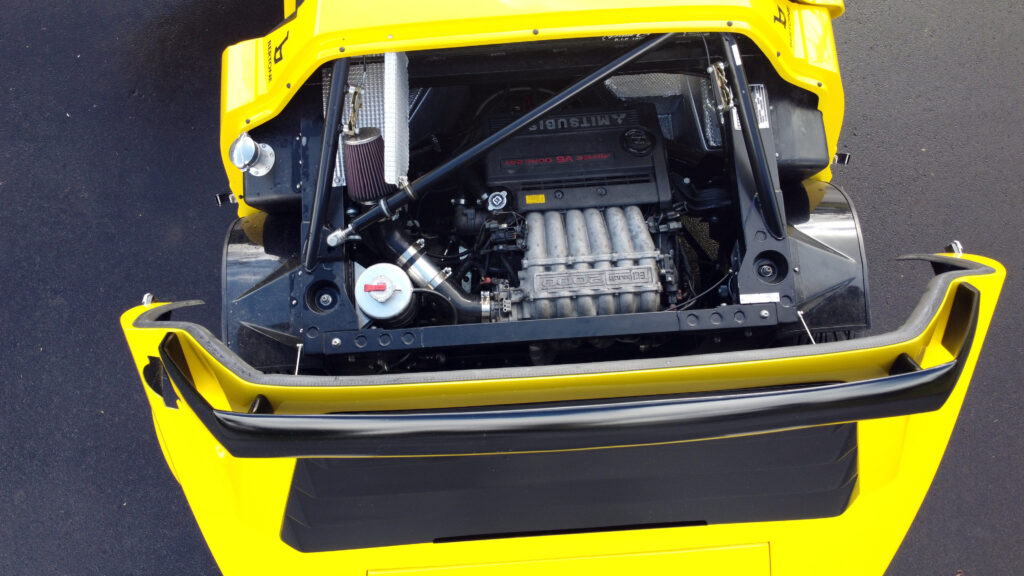

The main component not included in the kit was the engine. The criteria for engine choice were that it had to be a quad-cam V6, with the same firing order as the original Dino to give a similar sound, and it had to have a displacement of two litres so it could race in the same class as Craig’s BMW2002 rally car. This ruled out the Toyota, and the Dino was not even close to being affordable, so Craig chose the Mitsubishi FTO 2.0-litre V6, which has almost identical power to the original Stradale. At the time the FTO was a good choice as they were everywhere. Five years later, they are all but extinct.

The first task had been to buy a manual FTO donor car. Not all are manual or have the MIVEC engine in them. However, they found one in good mechanical condition and had a lot of fun punting it about while waiting for the kit that would enable it to be converted into a Stratos. Even better, it failed its warrant just as the kit arrived. Good timing. They could start stripping it down with no regrets.

Once the engine was out, Craig started experimenting with gear linkages, as the engine is front-mounted in the FTO and mid-mounted in the LB kit. The package from England did come with a gearstick and linkages, but the arrangement was backwards so Craig had to add more linkages to get it to work.

Midwinter Christmas

It was a big day, in July 2018, when the kit arrived in a large wooden crate. Packed around the body panels was theoretically everything Craig needed to build the car, right down to the nuts and bolts. Annoyingly, a large number of the parts were unlabelled so when it came to fitting it was a matter of ‘suck it and see’. An example was a packet labelled, ‘Sheet metal set’, with no further hint about which sheets of metal it might be applied to. A friend who was helping them accidentally threw out some packing without seeing any indication that it was the insulation foam for the rear bulkhead.

On top of that, Craig was using a different engine – deciding what should go where prompted more head-scratching.

There were a lot of light-bulb moments, when Craig would be working away on something and suddenly realise he had found where an odd piece of sheet metal that had puzzled him earlier actually belonged.

An important component that was not part of the kit was a build manual. LB does not produce one. It loftily assumes that if you are capable of buying a kit then you should be capable of building it. I have enough experience with kit cars to know a build manual should be a mandatory part of any kit. What is obvious to a kit’s designer can be far from obvious to a first-time builder, or even a builder familiar with other kits. Mid-engined cars are especially tricky as you often have to adapt elements from different layouts, and the absence of a build manual makes it considerably harder.

Luckily, having built several rally cars in the past, Craig did have the necessary nous, but it would be very frustrating for builders without his experience. Fortunately, this is the era of the internet. Having the ability to go online and see what other people had done was an asset. Seeing tutorials of people making the same mistakes, not so much.

Lacking latches

One thing missing from the kit was the Fiat X19 latches that are used to hold down the bonnet and boot. Fiat X19s are even less common than Mitsubishi FTOs. The Stratos needs four latches and an X19 comes with only two. After much hunting, Craig and Suzie found somebody in Timaru who was hoarding them. This necessitated going on an instant holiday from their home in Pukekohe to Timaru so that they could unbolt them from the car. The good news was that the kit had included a Fiat X19 steering column. The bad news was that, as a collet had been welded onto it by LB Specialist Cars, it was no longer compliant with LVVTA requirements. Without LVVTA compliance it can not pass certification in New Zealand.

After a bit of puzzling, Craig solved his steering issues by designing and getting machined a special steering shaft to fit the X1/9 column so that it would take the FTO steering hub and utilise the FTO switchgear on the X 1/9 column. This was easier than it sounds as, thankfully, the FTO column and the X1/9 column are the same diameter.

Interestingly, one of the most difficult jobs was fitting the sun visors. Craig ended up wandering around his local Pick-A-Part for most of a day hunting for something that could be suitable. He had looked at more than 100 cars before Honda Accord ones were deemed suitable, then, as he was leaving, he found a Subaru Omega Vortex that also looked pretty good. The resultant sun visors were a mash-up of both of them.

Although Suzie and Craig were making fast progress, the Covid-19 lockdown early in 2020 was a good opportunity for Craig to get the wiring installed while Suzie beavered away getting the body smooth enough not to paint. Yes, you read that right. This car is unpainted. It is still in the gelcoat it came out of the moulds with

a tribute to LB’s workmanship.

The finished car has been built as a Stradale, fully carpeted and sound insulated. The instruments are aftermarket and look period correct. Although built as a street car, the vehicle came with a built-in roll cage, for which Craig has obtained MotorSport New Zealand approval.

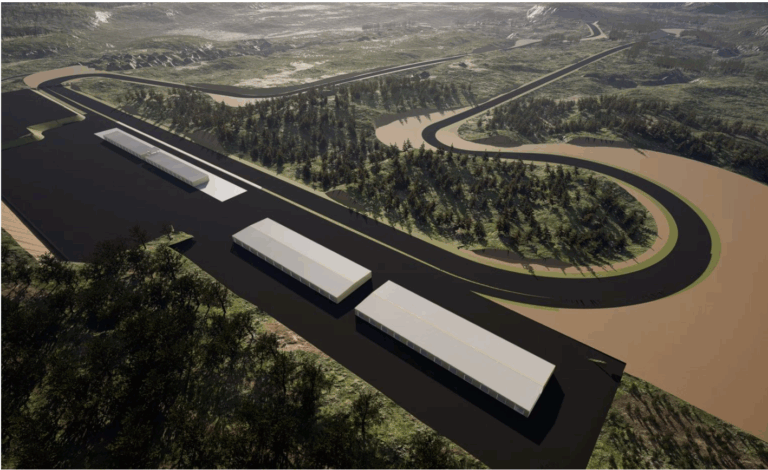

The car passed through certification and got its plates in December 2020. It is unlikely it will ever see gravel, although Craig intends to use it for track days. The Stratos has already been driven in anger around the Chris Amon track in Manfeild.

So, what do you do after you have built one of the best cars that Italy has to offer? Well, you do it again. This time Craig is rebuilding one of the best cars that New Zealand has to offer. Craig and Suzie now own what can best be described as a barn find Heron MJ1, a supercar manufactured in Rotorua during the ’80s. This one included the aftermarket addition of several rats’ nests. When I visited, the pair were in the process of stripping it down, but, given their industrious approach, I’m sure progress will have been made since then.