When you see the cars he has given us, Leonardo Fioravanti deserves to be better known. After inquiring about some of his inspired designs, described here last month, Roger Adshead took up the great man’s gracious offer to meet in person on his next visit to Europe

By Roger Adshead

When it first occurred to me to write to Leonardo Fioravanti to ask whether it might be possible to ‘interview’ him, the most I had hoped for was to send him a list of questions. The subsequent delay in his reply had caused me to feel it was perhaps unlikely to happen. Imagine my pleasant surprise when he replied to say the delay in responding had been due to his commitment to an exhibition of his life’s work at the National Automotive Museum in Turin.

Somewhat emboldened by this, and realising that I would shortly be in Europe with a spare weekend at my disposal, I dared to ask whether he would consider meeting me at the exhibition. It would be the perfect place to conduct an interview and, to my delight, he agreed. They say that ignorance is bliss, but as I began composing some questions, part of me began to have second thoughts about the size of the task that I had taken on.

That suspicion was well-founded but the experience was exhilarating. Having met the man, who gave me an incredibly generous four hours of his time on a personal guided tour of the entire museum exhibit, and having subsequently read his book, Il Cavallino Nel Cuore, I found myself completely intimidated by his life and achievements. I would give it my best shot but I believe a mere magazine article could never really do him justice.

The more I learned, the more fascinated I became, and the more I realised that I had met a man who had arrived at the perfect place, and at the perfect time, to fulfil his life’s dreams and ambitions. How often does that happen, and how often are any of us lucky enough to meet such a person?

As I retraced Leonardo Fioravanti’s fateful journey from Milan to Turin in my rented Fiat Cinquecento, maxing it out along the autostrade in order to make the meeting on time, I had in fact no idea of the relevance of that journey until sometime afterwards. I apologise in advance for only telling a small part of the story, and I would encourage any of you who have a deeper interest to read his fascinating book.

Drawn to Drawing

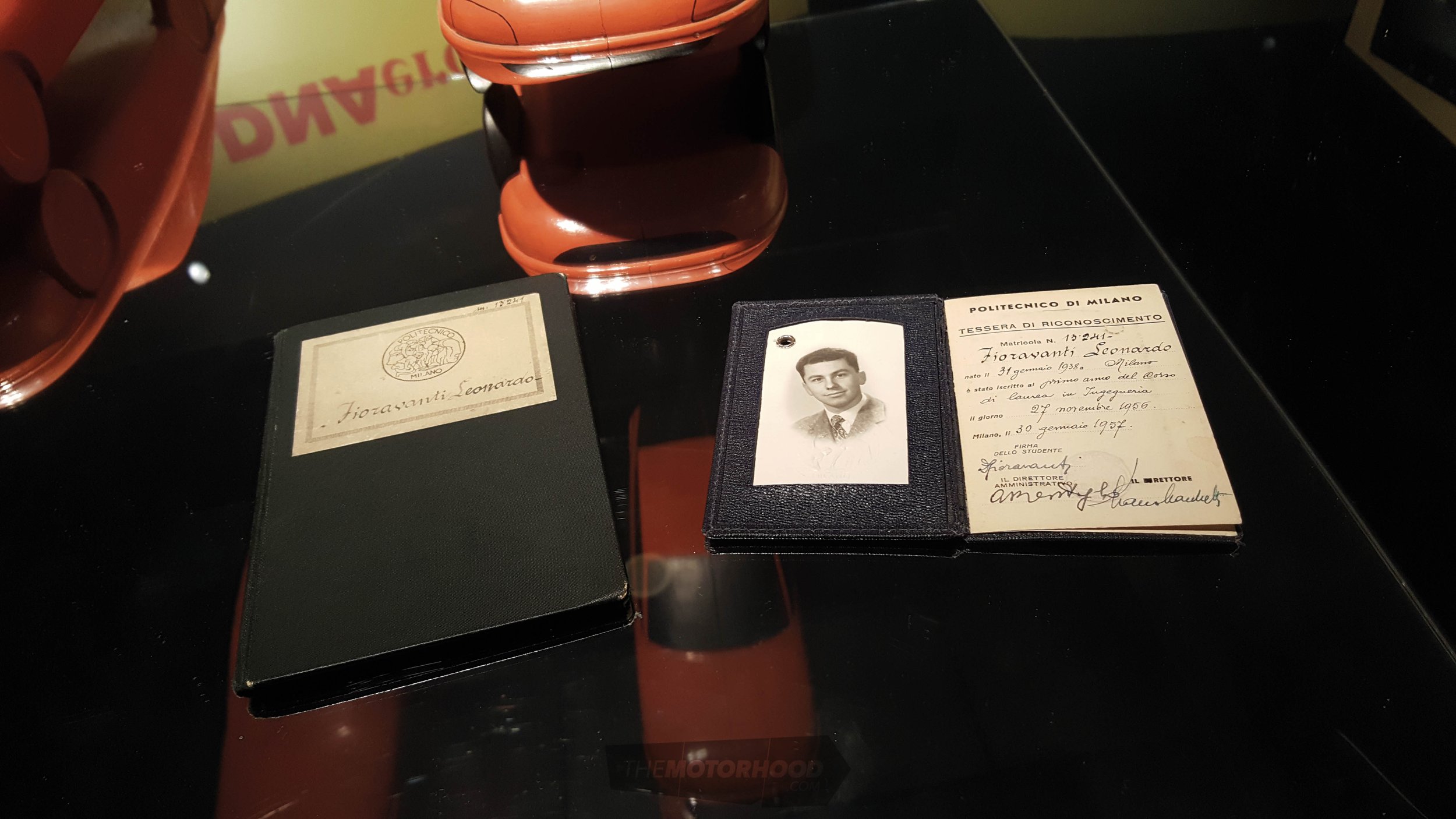

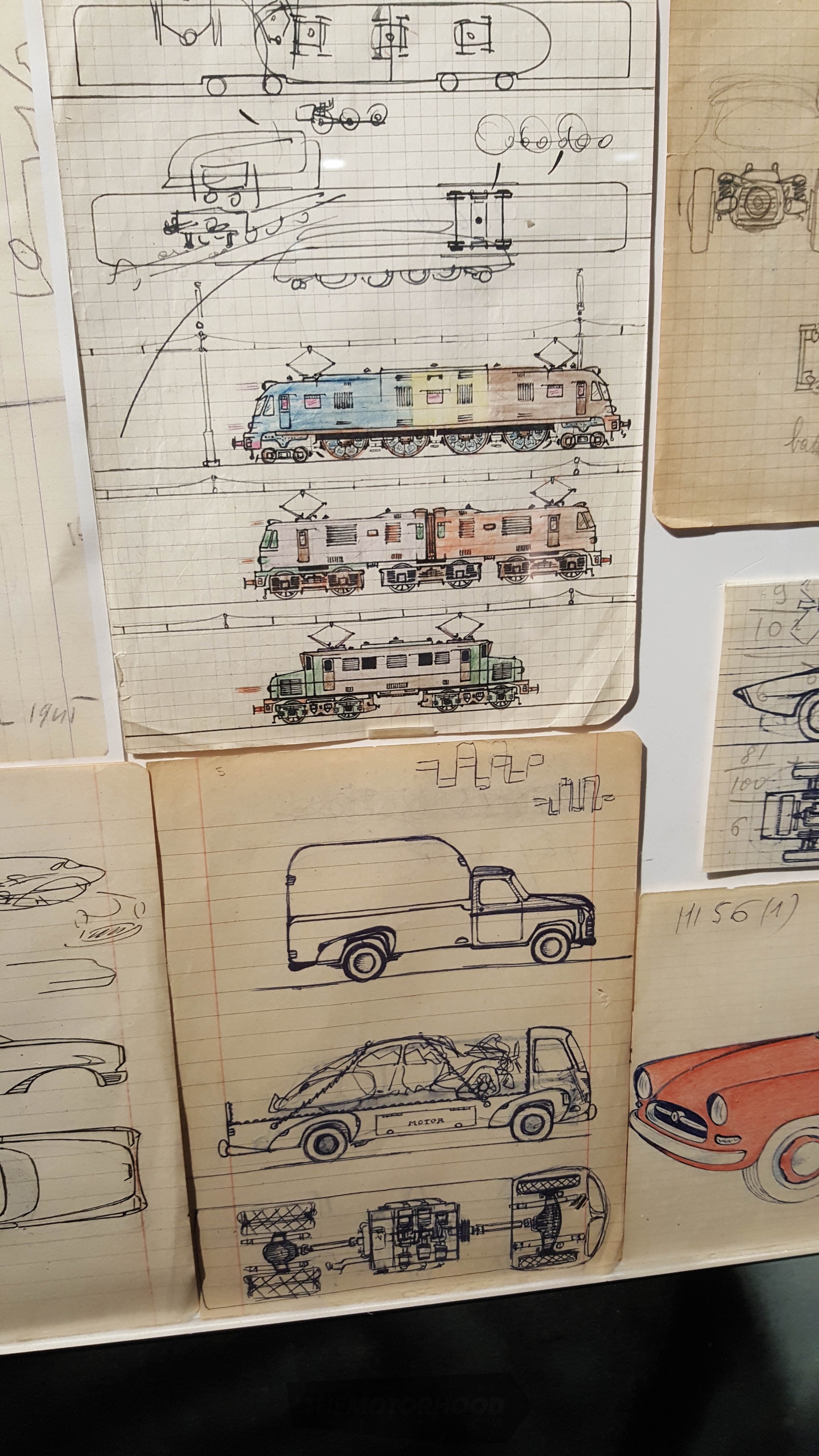

Born in Milan on 31 January 1938, Leonardo’s passion for drawing cars started at an early age and, by the time he was 10, he had become obsessed with all forms of transport, drawing cars and planes especially. He developed an understanding of aerodynamics from sailing with his father, and brought his understanding to his drawings. He developed an interest in driving in his early teens, when he and his friends would ‘borrow’ their parents’ cars at night, and drive around the deserted suburban streets of their neighbourhood into the wee small hours.

This obsession led to the desire to own a car, which he and three friends eventually did when they bought an ageing 1938 Lancia Aprilia cabriolet, which they ‘baptised’ Madonnone.

Meanwhile, he developed an interest in racing, which he also started to do clandestinely, borrowing his parent’s car for the weekend, tuning and partially stripping it before racing, and then restoring it and returning it by the end of each weekend. He went on to become an accomplished racing driver before being discovered by his parents in a quirk of fate.

They were increasingly worried by his continued tendency to allow his obsession with drawing to compromise his school work, and later his racing to compromise his mechanical engineering studies at Milan Polytechnic.

Having already become an ardent fan of the Ferrari designs coming from Pininfarina, an opportunity arose for him to join a group of students visiting Pininfarina HQ in Turin. The tour was led by Sergio Pininfarina and Renzo Carli. Leonardo had taken with him a large selection of his drawings, and at the end of the tour, he managed to effect an opportunity to show off his work, declaring his desire to quit his engineering degree at Milan Polytechnic, and come to work at Pininfarina.

After a pause, the two Pininfarina leaders — who were impressed by the young Leonardo and the thinking behind his ideas — suggested that he return to Milan to complete his studies, and then return to Turin when they would certainly hire him, telling him that one day he would become their general manager!

In effect, his journey from Milan to Turin that day, and its subsequent consequences, were what cemented his life path to become one of the greatest designers of Ferraris, and one of the greatest automotive design innovators period, with more than 30 patents to his name.

If luck, timing, and opportunism played a part in him arriving at that informal interview with Pininfarina’s leaders, it was surely his understanding of what went on under the skin, both from an engineering perspective as well as a dynamic perspective, combined with an innate understanding of and feeling for the skin itself, that convinced them that he had a unique skill set, and which no doubt prompted the comment about the general manager position!

Think about it — today Ferrari Spa employs test drivers, chassis engineers, powertrain engineers, aerodynamicists, and stylists. In Leonardo Fioravanti, Pininfarina had discovered one man with the complete set of skills. No wonder they saw him as the future of their business.

And no doubt this is why he was able to produce such a compelling string of Ferraris, that not only looked stunning, but also drove properly.

Living Legend

I arrived at the National Motor Museum in Turin just 10 minutes before our appointed meeting time. I am busy setting up a camera on a tripod in the museum’s café when I see him approaching. He is wearing an immaculate suit, and has piercingly bright eyes. He has both the confidence and the relaxed demeanor of a man who has spent a lifetime doing what he loves. He wears his 80 years incredibly well, as have the many beautiful shapes that he has penned.

Rather than a formal sit-down interview, he suggests we walk and talk around his exhibition: a personal guided tour with the man himself — what an absolute treat.

He clearly loves his subject, and speaks with huge enthusiasm about his early drawings, and the way in which his father, who sailed, taught him the language of aerodynamics — a quality he brought to all of his Ferrari designs, and which continues to this day. Seeing all the early drawings, I asked him about his inspiration. “Very simple,” he replies, “to express my ideas graphically.” And as if to emphasise the point, he adds, “I still believe that a freehand drawing is the quickest way to express an idea graphically.”

We move on to a giant picture of him stepping out of a Fiat Cinquecento (500), an original that he’d tuned for racing. With a real sparkle in his eyes, he tells me about his early exploits in his parent’s ‘borrowed’ car, driving with his mates through the deserted streets of suburban Milan in the early hours of the morning. Then he talks about how they bought their first shared car, and how they started to race it — all highly illegally and without driving licences. He loves racing, and went on to race cars for 45 years, his final race being in a Ferrari F40.

He tells me about his education, and how he came to work at Pininfarina, and I ask him to tell me about his first Ferrari design project. Somewhat incredibly, it was the development of the road-going version of the 250LM race car.

Called the Ferrari 250LM Speciale, it was for a very tall American customer, so Leonardo created a T-bar with hinged roof sections to allow easier access. He was determined to also optimise the aerodynamics of the original track car, and made changes which included an elongated front, and when the two cars were compared back-to-back, the road car was faster.

He goes on to say that he has always been committed to aero since his father first demonstrated its power and ability to create forward motion, even when sailing into the wind. In what he regards as one of his greatest achievements, he managed to persuade Pininfarina to invest in the first wind tunnel in Italy capable of testing full-size models. Lots of other manufacturers and coachbuilders subsequently brought their designs to Pininfarina for testing and evaluation.

At that point in our ‘tour’, a young male visitor had recognised the master, and attached himself to us like a shadow, hanging onto his every word. Leonardo pauses and explains that this is not a public talk, and that this gentleman — me — has come all the way from New Zealand for this opportunity. Rarely have I felt so honoured and so privileged!

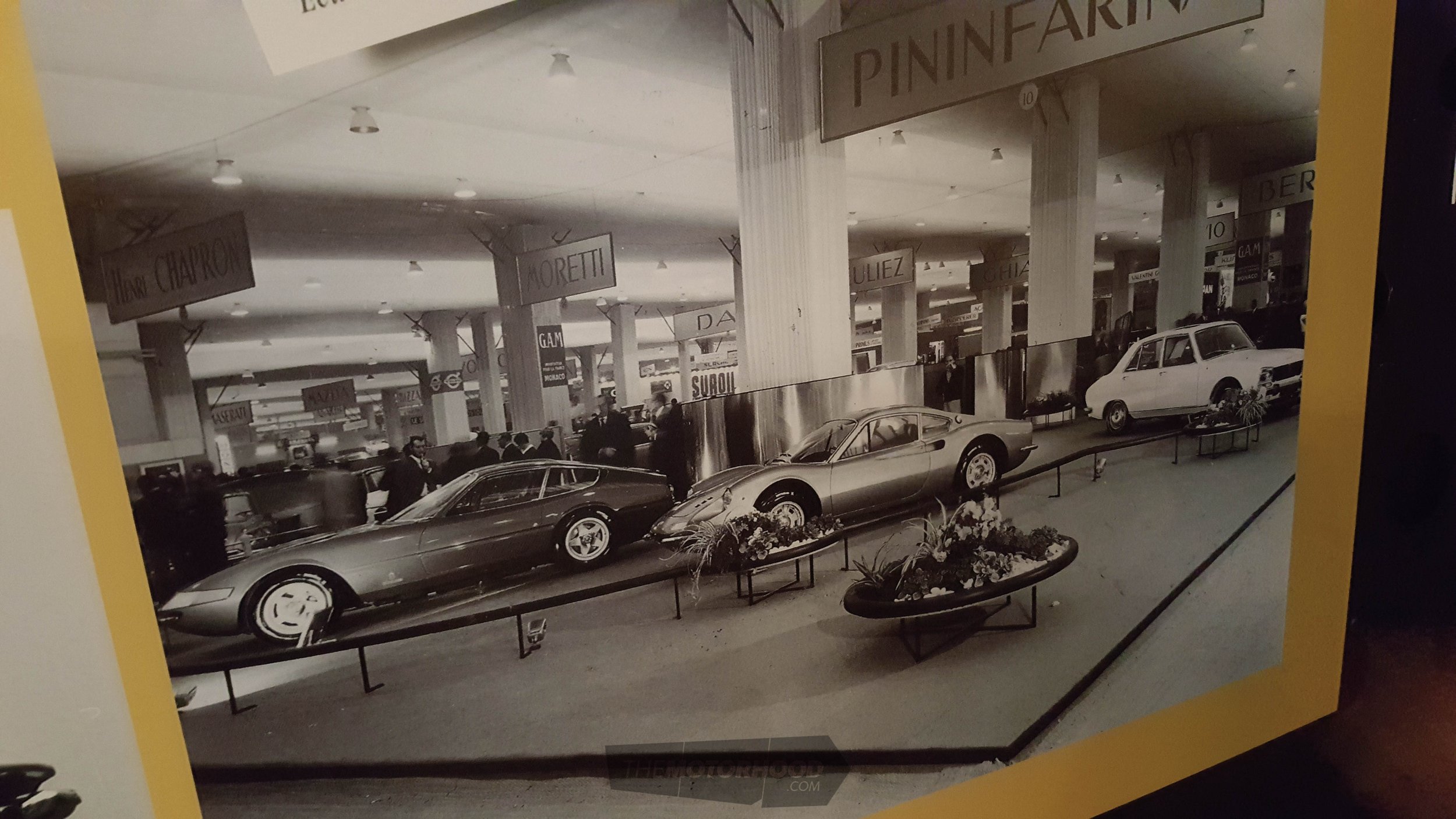

I broached the subjects of the Dino and the Daytona, both shown at the 1968 Paris Motor Show, where they shared a stand with the Peugeot 504. Their development could not have been more different. The Dino 206, later improved to become the Dino 246, was born a road car based on a mid-engined race car, whereas the Daytona was a road car that became a race car.

“The Dino was designed two years before the Daytona. ‘Il Commendatore’ [as he calls Enzo Ferrari] was known to be quite wary of mid-engined road cars. He felt that midship engines were good for racing, but not for road cars. He gave us the example of the horses being in front of the coach. I challenged this by saying that the hooves were also in front, and did he therefore also want front wheel drive? Up to that point, the midship engine had been reserved for road-going specials, like the 250LM Speciale, so in hindsight, it was a very big chance for me that my first job was to work on a mid-ship engined car for the road.”

Flipping Cheek

Leonardo explains that his major contribution to the 206 was persuading Ferrari’s engineers to turn the engine through 90 degrees to allow him to re-draw the shape, thus shortening the rear, and producing the beautiful balanced shape that we all know so well. His other significant contribution was the development of the neat little door handles above the belt line — a solution for which he still holds a patent. They were subsequently used on the Daytona, and on various other Ferraris that he designed.

“There is quite a big difference between 206 and 246. The 246 had improved engineering over the 206, with input from Fiat. Not aesthetically, but the 206 was made of aluminium, and had some problems with load distribution. The 246 is steel, and this solved those problems.”

There was one important detail about the Daytona that I had been waiting for the chance to ask Leonardo to clarify. When his clean-sheet design for the 275’s successor was shown to Enzo Ferrari, he was clearly impressed. He asked Leonardo whether there were any details that he’d like to change. Leonardo says that he rather timidly asked for an extra 6mm on each side of the track, moving the wheels further out. Enzo apparently thought for a minute, and then said, “Agreed: 6cm overall then,” and the car went into production.

Leonardo explains that from this point on, he developed a very special understanding with Il Commendatore. Given his reputation for being demanding to work for, I asked Leonardo to explain his relationship in more detail: “The book is very precise.

After Daytona, it became automatic for me to be involved. He had an extraordinary strategic vision of things and men, but personally wasn’t in a realistic position to contribute. He could see very far but needed others to realise his ideas.” He explains that his dialogue with Il Commendatore had become synchronised to the point where only a few words needed to be spoken.

“Design me a car suitable to drive to La Scala in Milan,” was the brief for the 365 GTC/400i, resulting in a shape that both nailed the brief and enjoyed a production run of 18 years — the longest in Ferrari’s history.

“My dear engineer, make me a true Ferrari,” was the even simpler brief for the F40, and which produced a shape and a performance package which for many remains the original and best supercar, with a power-to-weight ratio that still compares favourably with today’s fastest models. No wonder so many of them found homes.

Fitting Farewell

The F40 was the last car that Enzo Ferrari personally signed off: “At the end of July he asked me ‘who knows how to produce this car?’ and by November I was asked directly by him to take on the project, despite the fact that at that point in time, Il Commendatore was only responsible for race cars, while the head of the Fiat group was responsible for road cars. After two or three days, the head of Fiat called me and asked whether I’d already had the call from Ferrari. After that, things moved very quickly, in order to get the car ready to present to the world’s press in Maranello, in July 1987.”

We start to talk more about design, and Leonardo emphasises his desire to distill each design challenge down to the simplest solution that is both compatible with its purpose, and consistent with its need to integrate seamlessly into the overall production. When I ask which of his designs is his favourite, he throws his hands in the air and exclaims that with so many to choose from it was impossible to choose just one. (Imagine being able to say that!) That said, we happen to be standing close to the stunning silver Daytona, and he reaches out affectionately to touch its roof, saying that this is one of his three favourites, and invites me to take a picture. He also comments that he prefers the original plexiglass version, which had to be changed to conform with US regulations.

Next on his list of three is the nearby turbine-powered Sensiva, which deploys a patented system of intelligent tyres, and is finally generating some interest from a mainstream manufacturer. ‘Wait and in time they will come,’ I think to myself.

His third favourite was still some way ahead in our tour, and turns out to be an all-electric open-wheel racing car — the LF1.We cut back to his days at the Milan school of design, and he shows me the early tools of his trade— a permit and a slide rule — which are part of the display, which also includes the realisation of his diploma thesis: the front-wheel drive, six-seater, aerodynamic package which spawned so many famous shapes from mainstream carmakers.

I ask him which is his favourite design detail, and he says, “You have already written about the round tail lights. In fact, I have a constant desire to express things in a simple way. I don’t like complex researched solutions. True projects are developed by logic, not by political things. I was elected to political office, but after five years I left office, disillusioned with politics. It is the most difficult life.”

We talk a bit about his career after Pininfarina, and he explains that he had one or two years with Ferrari, as vice general manager, and CEO of Ferrari engineering. He adds, “When I wrote the book, I came to know me. And now, with this exhibition, and so many questions from young engineers, I have finally come to know myself.”

The Other Leonardo

I comment that he has a very appropriate name. He laughs and says, “Recently one of the journalists writing for the top Italian newspaper wrote ‘Leonardo da Milano’. Crazy journalist! In fact, my father was a maniac [his words] of Leonardo da Vinci. Latin people say Nomen omen … the name maketh the man perhaps?”

Switching back to design, I ask him whether the ever more complex safety and aerodynamic requirements are placing limitations on designers. “Absolutely not. It’s the approach that matters. Nowadays the approach is commercial … all about sales and marketing. Go back to engineering principles, and the outcome would be better. I have great confidence in the future of electric cars, for example.

“All current designs have a big hole in the middle [at the front] for cooling the radiator, and two holes at the side, which in most cases are fake. Like the Americans after the war — fake! For me the key to good design comes from function, then aesthetics, then interpreted with personal style. This is my approach.”

I comment that the current head of Ferrari design has made reference to safety and aerodynamics influencing the way the current cars look. Leonardo says that for him it is not the problem. “If you don’t have new demands from safety and aerodynamics, you simply repeat what has gone before. It is good to have fresh parameters so that there are functional reasons to develop new designs … fresh challenges, to make an effort to improve.

“In the past, Ferrari used external designers, but has recently changed its approach. Now they only use internal designers. For years they have worked on developing this. When I proposed the special project SP1, it was an external design. Now even the SP one-offs are designed within Ferrari. They hate the comparison. Cut off outside ideas.”

Asked about the forthcoming SUV, he says: “It probably won’t be named an SUV. It’s driven by marketing and commercial forces.” He would not be drawn on what Enzo Ferrari might have said about it, and was keen to move on to the subject of electric cars, although he did say ‘Il Commendatore’ would have wanted to develop the best electric car in the world. He wanted to win. “I’m not sure with an SUV if you will win something — perhaps from a financial point of view — perhaps without that, not having the finance to sustain the core business.

“For me, Ferrari is the best of Italian history, but it is history. Many things have changed deeply. It is not the Ferrari it once was. Automobile design in Italy has fallen on hard times. The automobile is the first human product to be globalised, and our most recent client is Chinese.”

I comment that the current electric cars look like conventionally powered cars, notwithstanding the design flexibility that they offer. He comments, “I feel that many of the current designs are too complex and ‘grumpy’ looking. For me, the future of electric cars can offer fluidity of design and fluidity of aerodynamics.”

Will he design cars in the future? “Why not? But I like Italian cars. The small geographic area comprising northern Italy, southern France, and southern Germany has taught the world how to make cars, but prototyping and design is not enough to sustain the industry. The future is in China.”

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 371