In a rare foray into rallying reminiscences, Motorsport Flashback pays tribute to the Flying Finn that introduced Kiwis to the other-wordly skills of the top-level WRC

By Michael Clark

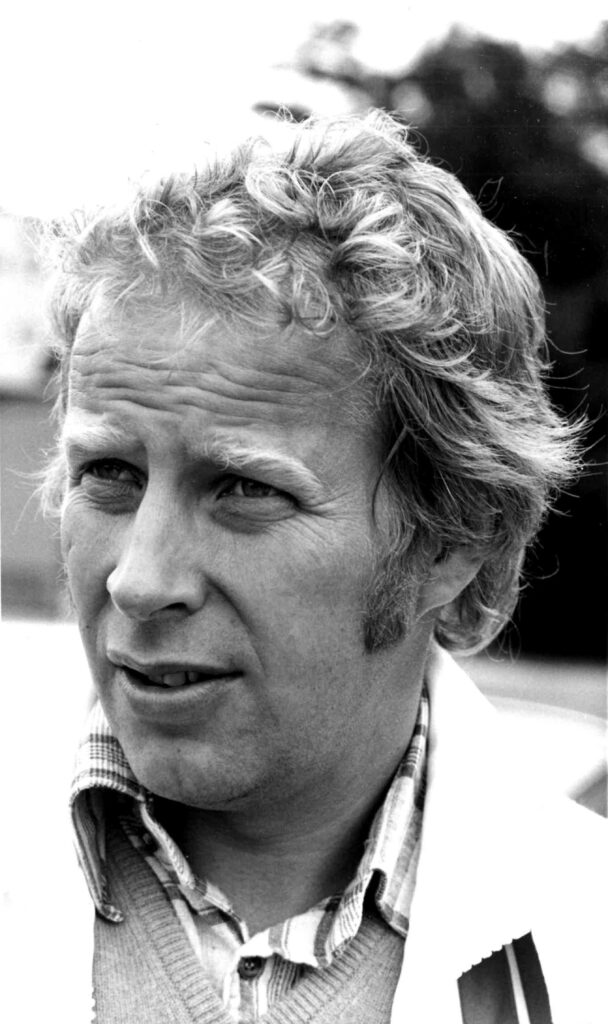

Hannu Mikkola

Rallying arrived in New Zealand in 1973 like a tsunami. It had been only a few years since the sport was introduced here and shortly afterwards Heatway came on board as the sponsor to take rallying to a new level. The 1973 Heatway would be the longest and biggest yet, running in both islands with 120 drivers over eight days and covering some 5400 kilometres. The winner was 31-year-old Hannu Mikkola — a genuine Flying Finn who had been rallying since 1963 before putting any thoughts of a career on hold until he completed an economics degree. The likeable Finn became an instant hero to many attracted to this new motor sport thing. I was one of them, so it was with sadness that I read of his passing in late February at the age of 78. Master mechanic Ray Stone pointed me in the direction of Dave Parton to assist with a tribute and I’m delighted he did because here is yet another quiet Kiwi achiever on the world stage, now running his workshop in Auckland. For three years from March 1977, Dave was a member of the elite Ford rally team working on the Escorts out of the famed Boreham base in Essex — the first ‘foreigner’ to do so. Within two weeks of arriving in England he was off to Kenya for the East African Safari. “It was only when I got back that I was interviewed for the job I already had …” but the formality was required to get on the payroll.

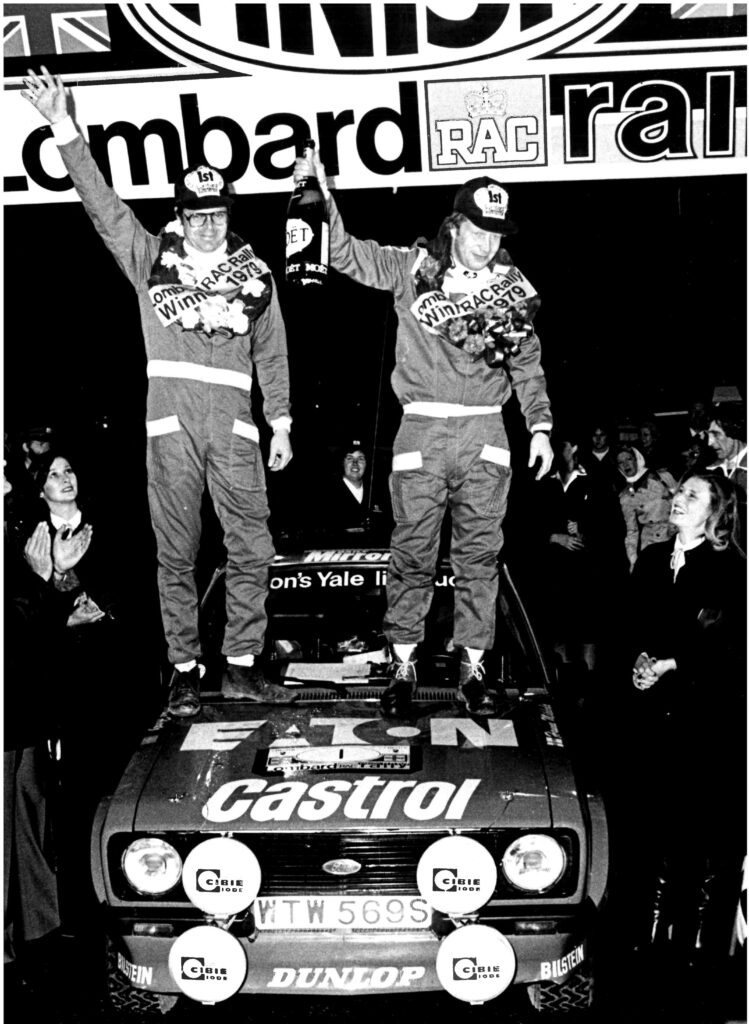

During the 1973 Heatway Dave was working primarily on the Escort of his good friend Mike Marshall and his efforts had clearly impressed the Ford bosses which led to the opportunity to move to England. “We were globetrotting all over the world.” It’s clear talking to Dave that he has huge regard for Hannu. “He was a really nice, gentle man – quietly spoken and not at all excitable like some of them. He had the ability to ‘feel’ the car and to preserve it to the end — just look at his record on the RAC from 1977 to 1984 — he won it four times and was second four times.” We agree that there is possibly no better record over eight years on one event in any form of top-level motorsport. Dave also gives a lot of credit to Hannu’s long time co-driver. “He had the benefit of Arne Hertz who did the route books for the service crews. They were good friends and really worked well together. Hannu was a real thinker and could relate to an engineer and tell them exactly what he wanted.”

I wondered if he ever spat the dummy? “He occasionally got angry but he’d walk away, calm down, and think rather than screaming and shouting like some … he was nice to work for. And he could tell a good car from the others.” I suppose, because of the ’73 Heatway, I initially associate Hannu with the dark blue and white Mark 1 Escort, but by the time Dave arrived at Boreham they’d moved onto the equally dominant Mark 2. “That period, when I was at Boreham, was the ultimate time of two- wheel-drive rallying.” The goalposts, however, were about to be moved forever. Dave recalls Hannu’s move to Audi and the game-changing Quattro. “He was amazing in that … he was actually testing it while he was still at Ford.” I wondered if the Ford hierarchy knew about that. “Well, we all knew …”

Hannu’s co-driver on the ’73 Heatway was legendary navigator Jim Porter who described the Finn’s intuition as the most startling thing about him. “He knows what’s coming up next. Once you’ve seen how quickly someone of Hannu’s standard can take you over a special stage, it soon kills any ideas that you might be able to do the same.” It’s a regular theme that Hannu Mikkola’s smoothness made going blindingly fast look effortless. The move from Ford to Audi gave him his only world title, in 1983, but the driver’s championship had only been around since the late 1970s. There is no doubt more world titles would have gone his way had the championship started a few years earlier. Between Ford and Audi he was hired by Mercedes-Benz and indeed won the Rallye Côte d’Ivoire in a 5-litre 450 SLC. Hannu’s final WRC win came in 1987 on the Safari with an Audi 200 after which he moved to Mazda. He remained part of the Japanese manufacturer’s squad until semi-retirement in 1991. He put a complete stop on competition two years later. He had scored 18 WRC victories and 44 podiums, cementing himself as one of the giants of rallying and a true hero of the many Kiwis who watched that Woolmark-sponsored Escort dancing its way from start to finish a mere 48 years ago. And heading the list of his admirers is Dave Parton who came to know him better than any of us.

Aston Martin

Such was the speed at which the design of F1 cars evolved six and a bit decades ago, there were two entries into the upper echelon of motor racing with models that were obsolete by the time they were built. Both the Scarab and the Aston Martin DBR4 were good looking bits of kit, the former being the indulgence of super-wealthy American driver Lance Reventlow, finished in a distinctive metallic blue and white body. Having just won the 1959 version of Le Mans, Aston were ready to take on Ferrari on the number 1 ground — their beautiful creation in a lovely shade of lightish green that must have confused those who really believed there was a darker colour called British Racing Green.

Scarab, named after an Egyptian dung beetle, have become effective cars in historic racing, enough to suggest that in a period – had they ever been developed and driven by top pilots – they could have been contenders. But by 1960 the front-engined concept was well and truly finished. Scarab soon afterwards sank without trace. Aston Martin, of course, have made a precarious living providing the planet with some of the most desirable sports cars. Aston was on the brink of bankruptcy prior to being rescued by Ford, but now they’re re-entering Formula 1, 61 years after the short-lived flirtation. The headlines inevitably refer to the ‘British Ferrari’ in their striking green livery, which will have four-time world champion Sebastian Vettel as lead driver. We wait to see, based on the Italian team’s poor performances in 2020, whether Aston Martin will fare even better than the famous red cars in their return to F1.

Mo Nunn

I hope to never again be opening the latest issue of this magazine in a hospital bed, but it was in a cardiac ward that I ripped into the March issue after spending only the second night of my life in a ward since I was seven. My wife had brought in the latest New Zealand Classic Car. I was already waiting to be discharged when I saw it. Last month I had been recalling getting the autograph of four-time Indy 500 winner Rick Mears, I then found myself reading that it was the American who had employed Chris Amon at Ensign. It was nearly enough to put my ticker back into the arrhythmia that had landed me there in the first place.

For the record, Rick Mears was a good-looking Californian who never drove in F1 but was good enough to. Morris Nunn was the perennially underfunded owner of the Ensign F1 team from the English Midlands. He also had a comb-over. There was a time, in the late sixties, when ‘Mo’ was one of fastest and most successful drivers in the proving ground that is F3. Like Mears, he would not have disgraced an F1 grid but ultimately started building Ensigns for F3 before making the massive leap into the bigtime in 1973.

I sincerely apologise for any confusion and hope no other cardiac moments were initiated as a result.

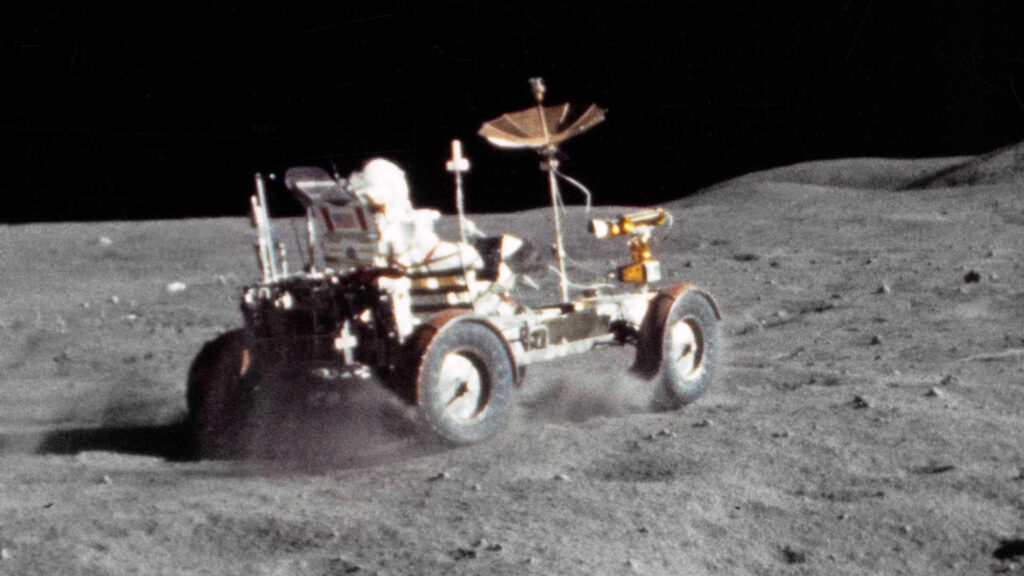

LRV-1

For nearly 20 years this column has focused on the world’s best drivers and the fastest cars. However, in a moment of what can properly be called lunacy, on discovering that it was in April 1971, 50 years ago, that the world’s most expensive car was first tested, I couldn’t let that anniversary go unmentioned. It was from the Apollo 11 mission, in July 1969, that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin emerged from ‘the Eagle’ lander to become the first men to walk on the moon. Having cracked that bit, the urge to go further was strong, and for Americans that meant by car. Enter the LRV-1, the ‘Lunar Roving Vehicle’ or, more colloquially, the Moon Buggy. It was delivered to Nasa half a century ago, built by Boeing, its wheels, motors, and suspension coming from General Motors.

The cost was US$38 million. I haven’t ‘time-adjusted’ that to reflect half a century of inflation — that was the cost in 1971! For that Nasa received a four-wheeler, three metres in length with a range of 92 kilometres. It weighed 210kg on earth, but only 34kg up there. The four engines produced a combined total of a single horsepower and were battery powered. LRV-1 went with the Apollo 15 mission offering the alluring promise of major scientific discoveries, thanks to the greater distances the astronauts could cover. The vehicle, a two-seat convertible, was designed to achieve 13km/h but an Apollo 17 pilot achieved 18km/h aboard the penultimate Moon Buggy which therefore holds the unofficial land-speed record for the moon.

When the Apollo 18 mission was cancelled, LRV-4 remained on Earth meaning that the other three are still up there, quietly waiting for the first Lunar Grand Prix.

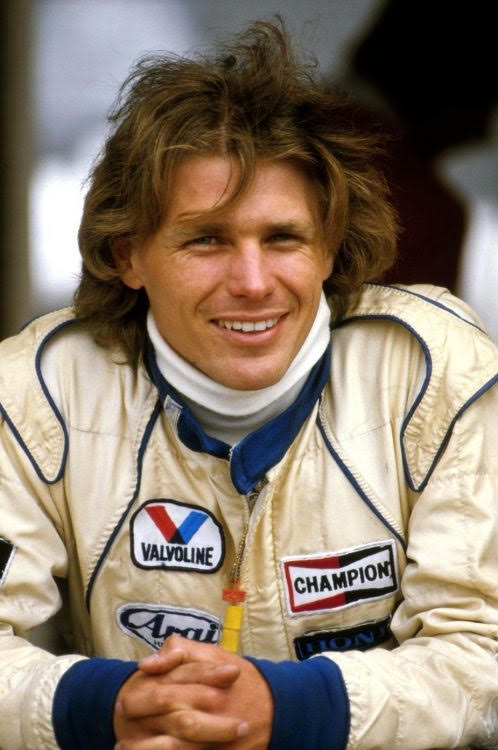

Mike Thackwell

It’s so long since we’ve seen photos of the reclusive 1984 European F2 champion that it’s hard to believe he could be 60 because he pretty much faded out of motor racing well before his 30th birthday. Despite being born in Papakura at the end of March 1961, he’d largely grown up in Western Australia, although he always insisted on being referred to as a Kiwi. Motor racing took him to the UK in the late 1970s and while still a teenager he was being touted as a future F1 star. It never happened but that probably has more to do with Mike than anything else. There is no doubt he had the talent. It was a career that could have been, but he is not the type to have regretted how things transpired for a moment. He’s been based on England’s south coast for decades, and his time has been split between various activities ranging from flying helicopters to North Sea oil rigs to teaching severely disabled kids. He says he was born in the wrong era and would have much preferred motor racing before the days of sponsorship and PR.