By Donn Anderson

Photography supplied by Donn Anderson

Riding in a genuine Ford GT40 with Geoff Manning is like living a slice of automotive history, as Donn Anderson found out over three decades ago …

The phone call in 1990 was dead easy to accept. Geoff Manning was ringing to ask if I would like to spend some time with the only genuine Ford GT40 to have driven the roads of New Zealand. There was little time to ponder since the car was destined to return to England and new owner Ted Rollason.

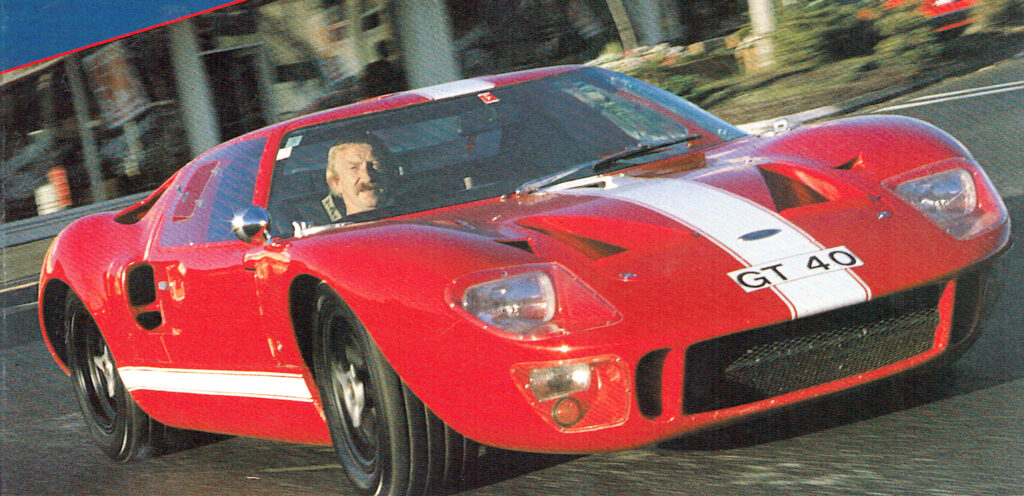

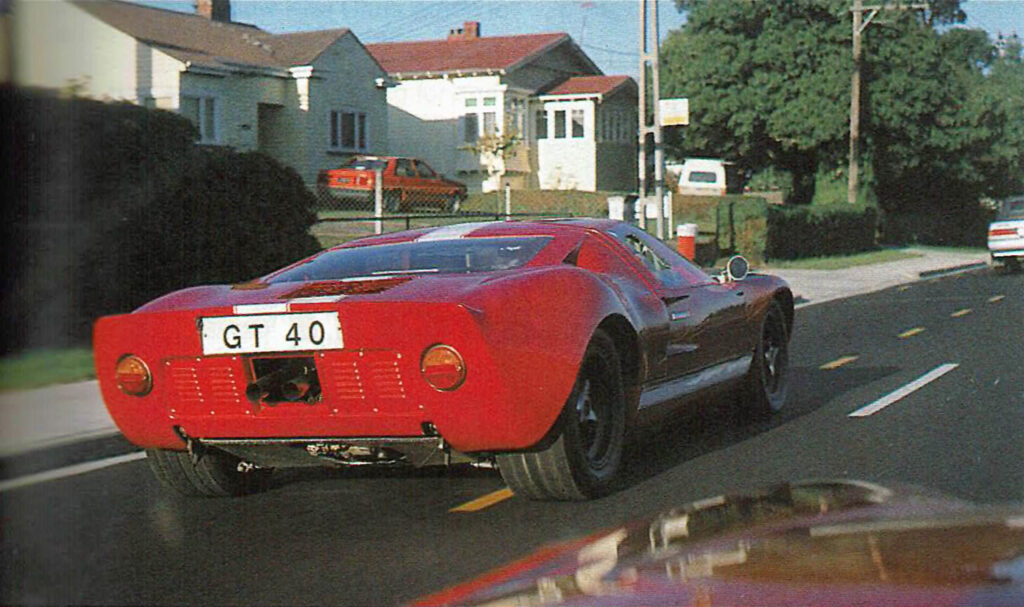

My answer, of course, was positive and immediate — and what a rare and fleeting experience a few days later to be driving around Auckland streets in such a stunning and wonderful machine. It was soon to be reunited with Rollason, a doyen of the historic racing movement in Britain and who is currently on the board of the Historic Grand Prix Association. Circling the busy Panmure roundabout and heading for suburbia, there was almost no time for photography as I savoured this special moment.

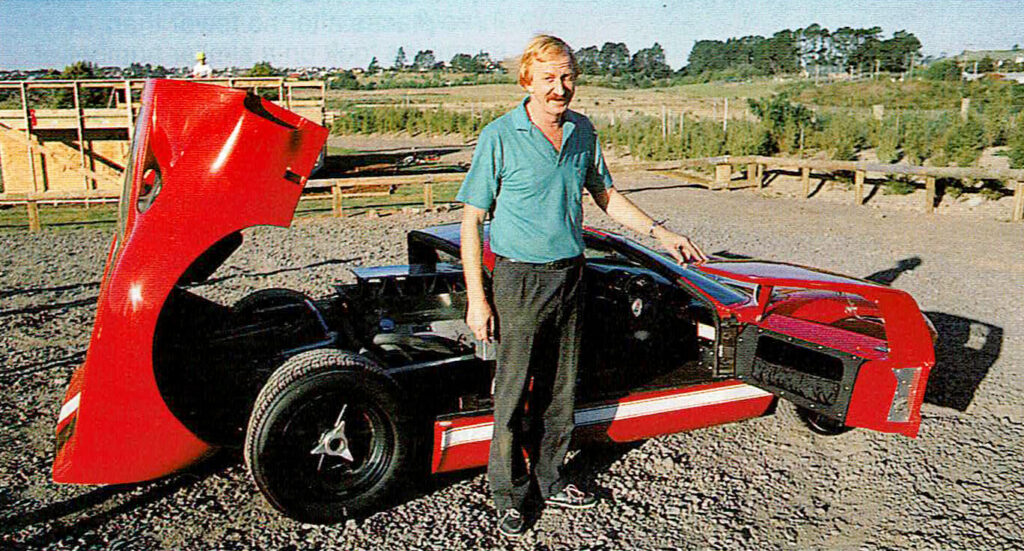

We sorely needed the wide open and traffic-free spaces Auckland is famously not known for, so this foray could only be a small taste of what the car had to offer. Few of the motorists we shared the road with would appreciate the significance of the red and white striped, low-slung GT40. However, when we paused to take a few snaps, four young school lads were drawn to the impressive beast and were treated to an inspection of the lusty V8 in the mid-engined machine.

Geoff was a mechanical genius who came with the proper credentials to refurbish and care for the GT40 while it resided in New Zealand. After all, he had been chief mechanic on the McLaren/Amon Ford GT40 for the victorious 1966 Le Mans 24 hour race assault and his CV listed many other motor sport achievements as a talented spanner man. Geoff showed me around the car, seemingly knowing every nut and bolt while musing somewhat sadly on the hugely escalating values of such iconic vehicles.

Skyrocketing GT40 values

We tried hard not to major on values and, instead, absorb the sensations. One positive aspect of the skyrocketing value of the GT40 is that each and every one is carefully preserved. While driving amidst Auckland traffic we took comfort in the knowledge that if someone hit us or we hit them, no matter the damage, the car would always be worth repairing!

In 1965, a new production GT40 could be acquired for the equivalent of around $14,000, but values steadily decreased until 1971 when you could pick up a used example for $10,000. A 1971 advertisement in the British motoring weekly Motoring News read: “Ford GT40, 4.7 engine, ZF box. New tyres, spare set of wheels with wet tyres. UK duty paid. £3500. Serious enquires only to …” By 1974 values were on the move with $30,000 more a ballpark figure before prices went through the roof.

The New Zealand Classic Car story on the replica GT40 in the January edition reckoned only about 50 of these cars were built, but three decades ago Manning understood a total of 87 Production P-Series cars were made — and at that time all were still in existence, including those that had been written off in racing accidents. Total GT40 production, including Mirage, Mark III, and prototypes amounted to 133 units.

Racing the Italian Volpini

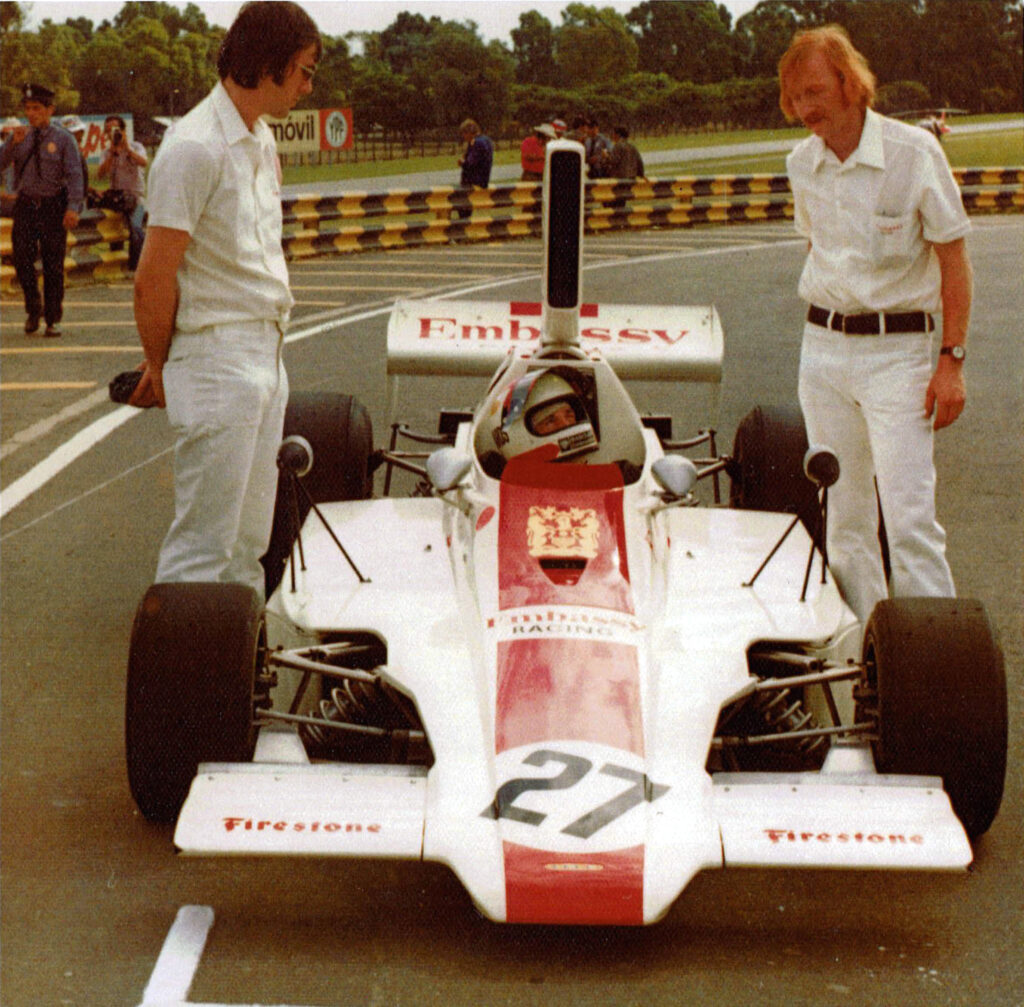

Dunedin-born Geoff Manning had cars in his blood from an early age, racing specials on home turf before arriving in Britain in 1962 where he joined Ford on the production line. He worked in Ford’s competitions department under designer Len Bailey and had a hand in development of the Mark 1 Escort for racing. He had a lengthy career as a mechanic in Formula 1 including working with McLaren, Williams, and Graham Hill — all this plus his extensive experience with GT40s.

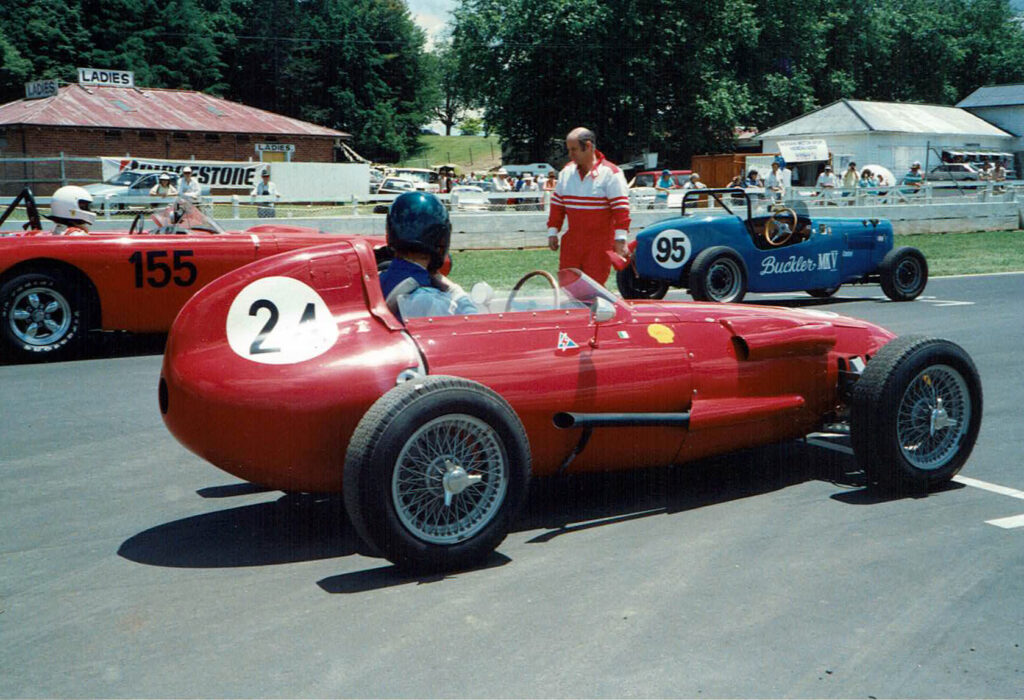

A highlight of Geoff’s sporting motoring life was ownership with wife Barbara of the beautiful front-engined 1958 Volpini single seater, chassis 013 — the very car in which Lorenzo Bandini won the Italian Formula Junior championship in 1959 before going on to become a Ferrari works driver. One of just 15 examples, 013 was sold to Count Johnny Lurani, originator of the Formula Junior series, and was driven by Lella Lombardi before the Mannings acquired the machine and brought it back to New Zealand for restoration.

The Volpini made a local debut at the 1989 Ardmore Grand Prix reunion and in the hands of Geoff was a four times class winner in the Thoroughbred and Classic Car Owners Club (Taccoc) series. Geoff could count around 90 race meetings and competition in more than 300 historic and classic events in his portfolio. He was also a well-respected scrutineer and the driving force behind the Historic Racing Club (HRC), along with Hampton Downs instigators Tony Roberts and Chris Watson. Today Barbara is still a tireless worker for HRC.

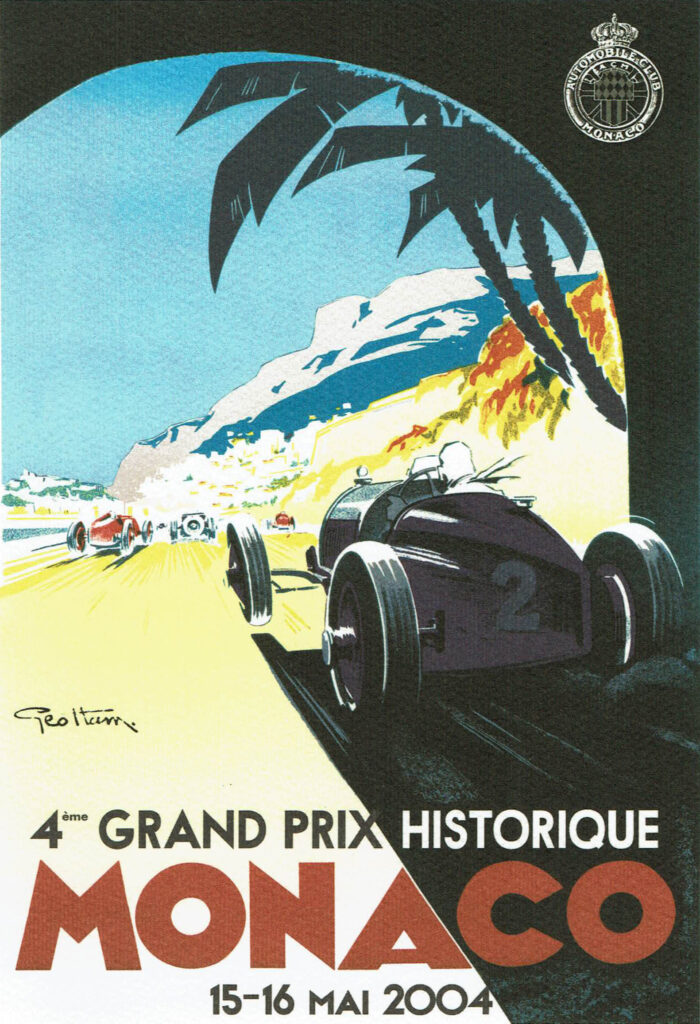

Geoff was diagnosed with cancer and, while out-living his doctors’ expectations, passed away in 2005. Knowing his time was limited, he and Barbara sent the Volpini back to Europe in what was an expensive but worthwhile experience, competing in the 2004 Historic Grand Prix at Monaco and in the historic race on the Pau street circuit in France. Together with Rollason, he also took part in the Classic Adelaide rally in a Gullwing Mercedes. Meanwhile, in 2005, the Volpini moved safely into the care of Allan Woolf.

A GT40 for sale in Tauranga

Ted Rollason recently took up the story relating to his GT40’s Antipodean adventures, remembering he almost lost touch with Geoff after the New Zealander returned home in the late seventies. “Fortunately we tenuously maintained our ‘muckership’ and as a result, he persuaded me to come down with my 250F Maserati for the Ardmore Reunion in 1989,” said Ted. Due to a docker’s strike, the Maserati failed to arrive in time for Ardmore and had a mixed run at Wigram where Ted was appalled by the tragic accident of James Clark. “I decided to stop racing old cars and sold the 250F when I got home,” said Rollason.

His enthusiasm was reignited when Manning contacted him to say there was a genuine GT40 for sale in Tauranga belonging to AC/DC band drummer Phil Rudd, who was wanting $450,000 for the car. Ted was immediately keen and asked Geoff to act as his agent to buy the GT40, provided it shaped up. Geoff arrived in Tauranga soon after but the price had already gone up to $600,000. Wisely Rollison was undaunted and agreed to the sale.

This was the 22-year-old GT40 I clambered into in 1990, chassis P1078 with a Weslake-headed engine and BRM wheels.The fibreglass bodywork was originally painted Borneo green and later dark blue as well as red. Delivered new to Geoffrey Edwards in the Channel Islands in April 1968, the car raced at Le Mans the same year, but it retired from that event. Mike Salmon and David Piper drove the Strathaven-entered car in the 1968 Brands Hatch Six Hour race and the Nurburgring 1000 kilometres, where it finished fourth, while Piers Forester and Alain de Cadenet ran it in the same German event the following year.

In the hands of David Weir, the GT40 crashed heavily at a Silverstone test session in 1970 and had to be completely rebuilt. The next two owners were John Etheridge (who rebuilt the car after its accident) and John Heath, before Scotsman Campbell McLaren acquired 1078 in 1980 and later sold it to Adrian Hamilton.

Rudd’s tenure began in September 1982. The car was shipped to New Zealand two years later where it stayed for six years until Rollason became the next owner. “The car captured my imagination as Geoff and I had rebuilt the Paul Hawkins 1019 GT40. I bought it, complete with the suspension damage that the car sustained when Phil threw it away demonstrating the car at Manfeild.”

South Island sojourn with a GT40

Manning began the rebuild, with Rollason sending a rear upright and other parts from the UK. “The first time I drove it was on a trip to the South Island,” said Ted. “The trip to the ferry, in the rain, overnight from Auckland was an experience. Geoff and wife Barbara were following along, towing the Volpini on a trailer behind a Jaguar XJS. Boy, was I glad to see them arrive on the jetty, still in the rain! We had a lot of fun in the South Island and had to do a clutch job which is nearly an engine-out job.

“How they changed clutches in these cars at Le Mans, I shall never know. You start by taking the seats out, raising the engine, having removed the distributor cap and rotor — all to facilitate drawing the gearbox back over the bottom cross member.” Ted figured one of the reasons the car was so successful, if a little heavy, was because everything “is massive”.

Getting the GT40 on and off the inter-island ferries posed a dilemma because of the low ground clearance and front overhang. But Geoff had thoughtfully raised the front abutments and the car did not ground at all.

“On the way to Christchurch, the engine ran out of oil after apparently I had wiped a pop rivet off the sump. Geoff in his imperturbable way removed a PK holding the wing of the XJS in place, fashioned a plastic washer out of an oil can and ‘screw-drivered’ it in the hole. Meanwhile someone in the gallery had been despatched down the road to get some Mobil 1;we filled the sump, kicked it in the guts, and continued on our way without any loss of oil pressure,” said Ted.

At Ruapuna Park for the Country Gents meeting Rollason felt he was coming to grips with the car. “I actually began to turn the car in rather than offer it to the corners, and I am very impressed by the high level of grip. A gentle learning curve is the order of the day with a car of such performance,” he said of that day 30 years ago.

What an experience, driving the GT40 more than 3200 kilometres on public roads on a return journey between Auckland and Dunedin. Ted remembers finding the noise “pretty horrendous” while rumbling along at a modest 2500 to 3000 rpm “with the rattle of pads, roll bars and shocks combining with the inlet roar and exhaust note to assault my ears”. All this while still averaging around 15 litres/100 km (18 mpg) from the 136-litre fuel tank during lazy highway motoring.

Just 40 inches ground to roofline

After sending the GT40 back to the UK in the hold of an Air New Zealand plane, Rollason ran the car in minor events at Silverstone, Montlhery, Ingliston and Snetterton, and also drove the Ford three times on the Scottish Ecurie Ecosse tours. By this time the car had its proper Le Mans spec engine, and shattering performance. Rollason said he could pull out, overtake six cars and pull in before anyone was aware he was there! After several years of ownership, chassis 1078 was sold to Peter Livanos who, with Aston Martin’s Victor Gauntlet, had a collection of admirable cars.

Of course you know where this competition-inspired Ford gleans the GT40 name tag since the car measures a mere 40 inches from ground to roofline. You clamber down into the cockpit, over a wide sill and lie almost horizontally, your bottom feeling as though it is about the touch the ground. Pull the curving door that reaches into the roofline shut, and the car envelopes its occupants.

The sequential gearbox is tricky and the car feels heavy around the edges. In the late autumnal sunshine it’s hot inside the cockpit, the engine sounds and feels as though it’s riding on the back of your neck, and wisps of exhaust fumes do nothing to dispel the claustrophobia. Once underway, things happen fast — the impressive acceleration literally hurling the car towards a corner. Despite this, the famous Ford feels secure, sitting flat, stable and confident.

The engine is free-revving, and the distinctive V8 soundtrack is a consequence of the cross-over manifold. Full harnesses keep occupants firmly in their seats. With the right gearing, the GT40 is capable of 346 km/h, or 215 miles an hour, and 100 km/h arrives from a standstill in less than five seconds. GT40s used a variety of Ford V8s, and the Rollason example had a 4.7 litre, 289 engine geared to a comparatively low 265 km/h (165 mph) at 6500 rpm in top gear, while at Le Mans the higher geared GT40s were doing just under 330 km/h (205 mph) at the same engine revs.

Early cars were unreliable

The GT40’s well-publicised Le Mans success in 1966 made up for massive defeats previously when the car proved hopelessly unreliable. One of the major problems was the weak Colotti 4-speed and Ford T-44 gearboxes, soon to be replaced by much stronger German ZF 5-speeder as fitted to 1078. Apart from accident damage, rust has been the major enemy of the car. The steel monocoques received little or no anti-corrosion treatment when new and, in time, suffer rusting in the sills. Rebuilding an original chassis is not easy and inevitably expensive.

In the flesh, the GT40 appears smaller than the 4178mm overall length suggests in photos, crouching on 15-inch diameter wheels, a 2413mm wheelbase, and measuring 1778mm in width. Originally known as the Ford GT when first unveiled in April 1964, the car arose from Ford’s desire to have an ultimate high-performance street machine that could win major races. The directive was to build a relatively simple car, powered by a modified Ford V8, and using North American technology and know-how as much as possible. Eric Broadley had the then-new Lola GT on the drawing board that effectively became the GT40. The car would not only be built in Britain but would use British design and organisational talent.

Today most GT40s live in North America and Europe, and in 1990 the lone example across the Tasman was owned by the late Bib Stilwell, a four-time Australian driver champion who also took part in historic races in the sunset of his competition career. While lacking in creature comforts, the GT40 is one of the last real sports/racing cars that can be sensibly driven on the road, as proven by Ted Rollison during his New Zealand travels. Even so, he had the warm reassurance of an experienced and enthusiastic Geoff Manning travelling not far behind, just in case.