The Birotor GS is a well-equipped and stylishly efficient design made even more intriguing by its amazing hydropneumatic suspension. It could easily have been the Peugeot 205GTi of its day, kicking off the hot-hatch trend some 10 years earlier

By Quinton Taylor

Polarising and quirky styling, innovative engineering — often with industry-leading technology — has always been a large part of the charm of the Citroën brand and the twin-chevron badge. Citroën’s brief dalliance with Felix Wankel’s little rotary marvel of an engine, which started in the 1960s, could have been another game changer for the French company. But it wasn’t to be. Reliability issues and poor fuel economy – just when the oil crisis made that an unforgivable sin – made the project uneconomic and almost an embarrassment.

FIRST WORLD WAR

The car firm founded in 1919 by André Citroën had its origins in industrial machining. However, André Citroën began making cars in 1908 when he took over the French Mors company, which they stuck with until the outbreak of the First World War. Citroën was a major producer of armaments during the war and it was during this time that André drew upon the example of Henry Ford in the United States and his mass production techniques. He determined that, if his factory was to survive after the war, he needed to build a capable, cheap and small car in big numbers. To do this he surrounded himself with engineers with technical expertise such as Louis Dufresne, formerly with Panhard. In 1917, he added Jules Salomon. In 1919, Citroën introduced the Type A, a 10hp car better equipped and generally more capable than most contemporary offerings. It had a water-cooled 1327 cc four-cylinder engine producing 13kW (18hp), giving a top speed of 65 kph. Significantly Citroen had acquired a Polish patent in 1900 for a double helical or herringbone pattern gear which he used in the final drive. It was the inspiration for the Citroën double chevron logo.

INNOVATION

The Type A was displayed in a showroom on the Champs-Élysées, which would become a focal point for introducing new models and contained a Citroën museum up until recently — a pity as it was an impressive display, but a new display address will apparently be announced when the world is ready for such things again. General Motors also came close to owning Citroën in 1919, but after negotiations it became clear the drain on finances was deemed too risky. Citroën would remain independent until 1935.

In 1924, Citroën formed a working relationship with US auto-body maker Budd, resulting in the Citroën B10, the first unitary, steel-body car made in Europe. It was displayed at the Paris Motor Show that year. The low-priced car sold well, and the construction technique was soon widely adopted, replacing wood-framed bodies. Citroën retained his low-price approach, but operating on narrow margins flirted with cash flow problems that would continue to haunt the company in coming years. Using the Kegresse track system, Citroën produced a range of military half-track vehicles from 1921–1937, which would be evaluated by the US Army Ordnance Corps and was the system used in M2 and M3 half-track vehicles, introduced in 1942. In 1940, the Germans also recognised the value of these vehicles when they occupied France and converted them for their use.

Citroën also involved his company in various expeditions around the world to prove the reliability of his cars. In 1925, a 1923 Type C Torpedo 5CV was the first car to be driven around the perimeter of Australia. Even more remarkable was the fact the car had already covered some 48,000 miles (77,000km) before setting out on the journey! The now restored car is displayed in the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.Bank Lazard came to Citroën’s rescue, buying up Citroën’s debts in 1927.

THE TRACTION AVANT

Ever the innovator, André introduced the first diesel-powered car, the Rosalie 15CV. In 1934, Citroën introduced the Traction Avant CV7, changing the motor industry overnight with its innovation, which still applies to car construction today. It had a unitary body with a prototype body developed by Budd, with no separate chassis, front-wheel drive, and independent suspension all round. It was a market success, but building the Traction Avant would involve a huge retooling cost for an all new design and a complete rebuild of the Citroën factory in five months. Allied with a costly advertising programme, the cost was too much and André Citroën filed for bankruptcy. The company’s biggest creditor, Michelin Tyres, became its biggest shareholder, with Pierre Michelin becoming chairman and Pierre-Jules Boulanger his deputy, vice president, and head of engineering and design.

Boulanger, a decorated World War I army captain, guided the company through the German occupation and assisted many attempts to thwart production of vehicles used by the Germans. Under the Germans’ noses, he oversaw the development of a car that would be as innovative as the Traction Avant when it was finally released in 1948: the now iconic 2CV, which remained in production until 1990! The 2CV was followed by the distinctive corrugated-metal-skinned Type H van which, today, is more enthusiastically sought after than ever as a business promotional van. The third would be a car that astounded many, the aerodynamic teardrop-shaped DS and ID saloons in 1955, which, even discounting its many engineering innovations, is revered as one of the world’s most cherished car designs. Boulanger died as a result of an accident in 1950 driving an experimental Traction Avant. His place was taken by Robert Puisseux who oversaw the introduction of the DS and managed Citroën until Pierre Bercot took over as chairman and managing director from 1958.

Under its extraordinary skin, the DS featured a single hydraulic system which powered the power steering, brakes and variable-height hydropneumatic suspension. It was a revolutionary world first and an engineering triumph, which gave the car an other-worldly ride, and mechanics the world over the heebie-jeebies. It also had a semi-automatic clutch and transmission for good measure. Its designation DS naturally encouraged the proud French to agree the car was indeed the déesse — the goddess. With production of nearly 1.5 million units from 1956–1975, it was a remarkable car for its time and is now obviously a first class classic. It showed the advantage of an aerodynamic shape, requiring just a small capacity engine to drive it along economically at an easy 160kph (100mph).

MON DIEU, UN ROTATIF!

Citroën made a number of erratic economic decisions in the 1960s, but then that was always part of the company’s DNA. The end goal was to expand its model range, especially in medium-size cars, to place less financial reliance on the more expensive and larger DS range.

Under French law, bigger engines attracted hefty tax penalties, so a new engine that offered high power from nominally small capacities being developed in Germany appeared to be the answer. The Wankel rotary was also light weight and small, ideal for the type of cars Citroën wanted to build. Its quirky Ami models had to get by on 600cc derivatives of the 2CV’s twin-cylinder engine. Citroën entered into a joint venture development programme with NSU Motorenwerke. A new company, Comotor, was formed in 1964 at Altforweiler, near Luxembourg, in 1964 to develop the engine.

Citroën acquired truck firm Berliet and car manufacturer Panhard in 1965, and it also saw the development of the first rotary-engine-powered Citroën, the Ami 8–derived M35. Prototypes were sent out to dealers for lease to selected customers to trial. The one-litre, single-rotor engine produced 106bhp (79kW), and it had a lot of potential. Just 267 of these little cars were made. However, at the end of the trial, Citroën was so convinced it was on the wrong track it bought most of the cars back and destroyed them. Liquidity was further challenged with Citroën’s acquisition of the Italian Maserati group, even though it gave us another classic: the hydropneumatic suspension–equipped and Maserati 2.7-litre V6- engined Citroën SM in 1968.

EVERYONE TRY TO CRACK THE ROTARY

Everyone from Mercedes to General Motors was developing a Wankel design. The Wankel engine’s compactness gave manufacturers extra space for passengers and safety, but it was thirsty. Mazda in Japan would be the sole company to persevere long term with the design.

But Citroën did not give up entirely either. Designed by Robert Opron, the GS Citroën was introduced in 1970. It was powered by a 55bhp (41kW) flat four, air-cooled engine and used many DS mechanical features, including the iconic one-spoke steering wheel. Its innovation, space efficiency, and sophistication were acknowledged with a European Car of the Year award in 1971. It was comprehensively equipped and one of Citroën’s biggest ever sales successes. More than 2.3 million GS and GSA models were sold. The award would also go to other outstanding Citroën models, the CX in 1975 and the XM in 1990.

Allied with the standard GS project was a twin-rotor–powered version substantially differently engineered and equipped. The Birotor was unveiled at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1973, and its specification was even more impressive than the standard GS models. It included hydropneumatic suspension, all round disc brakes (ventilated at the front), a semi-automatic transmission but at its heart was a water-cooled 107bhp (80Kw) twin-rotor engine. There was an even more powerful three-rotor engine in the wings for a bigger Citroën CX body, but just one prototype was built and later destroyed.

The Birotor was 70 per cent more expensive to buy than a normal GS. As with many designs around this era, timing was not good, as war broke out in the Middle East in 1974. Crude oil prices rose dramatically and affected sales of cars with poor fuel economy. Just 847 Birotors were built and few made it past 20,000 miles (32,000km) without overhaul.

Citroën made generous offers to buy back all Birotor GS models to avoid warranty claims and the need for establishing an expensive spares inventory, and many owners took up the offer. NSU sales of its Ro80 also suffered from an ever-increasing flood of reliability complaints, which it never managed to shake off despite being vast mechanical advances. It finished up being a remarkably capable car but, despite the Volkswagen takeover, just 37,398 cars were built from 1967–1977.

At Citroën, even a collaboration with Fiat couldn’t prevent a worsening financial situation, resulting in an intervention by the French government in 1974. Michelin and Automobiles Citroën merged with Automobiles Peugeot, with Michelin relinquishing control of Citroën to create PSA — Peugeot Citroën. Maserati was sold to De Tomaso, and Berliet was sold to Renault.

CITROËN’S IN HIS BLOOD

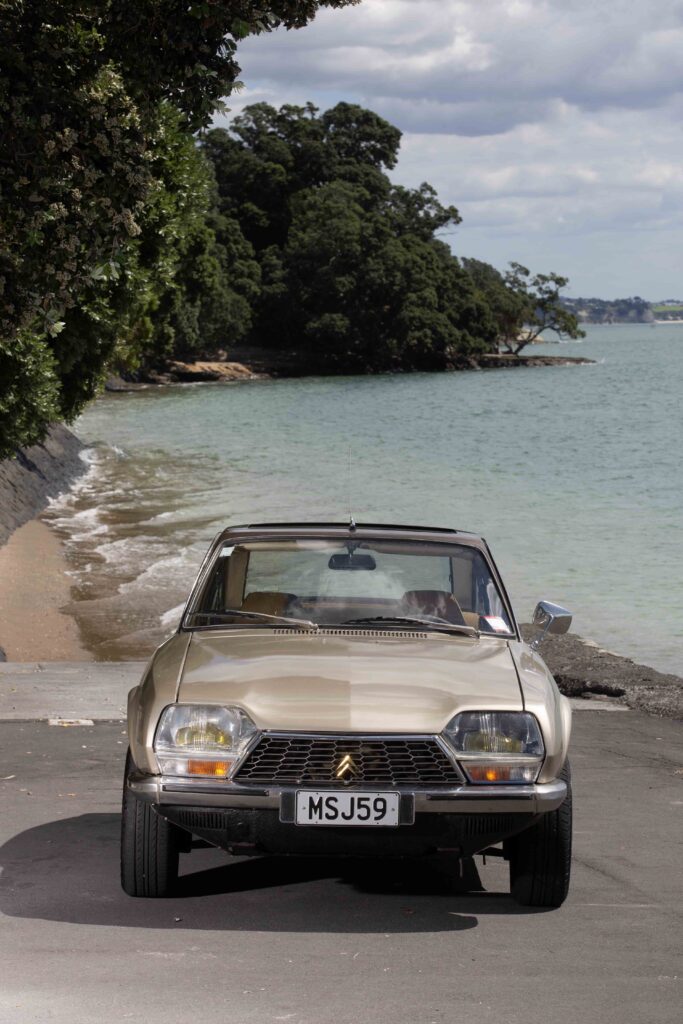

Kerry Bowman readily describes himself as a dyed-in-the-wool Citroën fan and a keen Citroën Car Club member. His Auckland home holds some of the chic French cars and many parts. He has also owned a number of examples of the marque as daily drivers, but he now drives a Birotor GS. They are rare, even in France, and this is a car which was not supposed to see the light of day outside France’s borders, yet somehow this one escaped the buyback to be one of the few survivors out in the world.

It’s a special car Kerry first saw while overseas in the ’70s, indulging an interest sparked early on by his father’s keenness for Citroëns back home in Tauranga. He was keen to see one ‘in the flesh’.

“I got interested in this Birotor when I bought a GS in Paris in 1972. I got in contact with Citroën Cars in Slough, and they got me an invitation to the Earls Court Motor Show where they had the first Birotor prototype on display. I said to a guy on the stand, ‘I’d like one of these,’ and he said I wouldn’t be allowed to get one. Citroën were building them for their own market to test them, and they were only left-hand drive.”

Despite its rarity, Kerry has always hankered after a Birotor, so when the opportunity came up a few years ago, he wasted no time. It is delightful to see this car, preserved in pristine condition, running sweetly on our roads — but it has been a far from smooth journey.

ENDLESS PAPERWORK

Kerry was keen to start the process of getting the car inspected and legal for the road, and he is grateful for the assistance of Citroën, Peugeot, and Renault specialist David Jones of Auto France in Manukau.

“I imported it in mid-2018. I went to register it, and it turned into a nightmare. First, we were told I needed a Low Volume Vehicle certificate for it. I asked for what reason and they said, ‘Well, because it has had a different engine fitted to it.’ I said, ‘That is the engine fitted to the car in the factory when it was built by Citroën.’ He said to me ‘I’ve never seen one,’ and I replied, ‘No, there are none in New Zealand; this is it.’ So I said Google it. He came back and I thought we were good.”

But things were just starting to warm up, as now the services of a specialist engineer were required, and the dollars were starting to mount up.

“They hit me with a rust search. So, we’ve got this rust certificate to do, and I had to get an engineer to come out and have a look at the car — over it and under it and everywhere. Then he (the engineer) says, ‘I’d like both sub-frames removed and the trim removed to the windows,’ so we did that, and we found a bit of corrosion in the bulkheads.”

A seam in the bulkhead was exposed when the engine came out, and this was found to have a bit of rust in it, so the engineer asked for the bulkhead to be opened.

“He said he would like me to open that with a hacksaw blade or a small file and clean the rust out. I opened it up and cleaned the rust out, and the next thing it was landing on the floor in the car. We got in and had a look, and in the bottom of the bulkhead it has got a channel through there which air goes into for the fresh-air system in the car. That had rotted the bottom out. Dave Jones took a look at it, and he was puzzled as to how it had rusted in that part, as it shouldn’t do that.”

The dashboard was removed, as it had to be repaired anyway along with the heater system and everything attached to it, revealing a bit of a surprise and the answer to the rust problem.

“I put my hand up in this hole and pulled out heaps of underfelt, which had come from under the floor carpet. It had been a home for mice. So we put new panels in, and the engineer was more than happy. He was amazed that it didn’t have the rust that he was expecting. All we had to do was a fabricated box-section behind the stainless steel bumper where the bottom had rotted out.”

There was also a gusset in a panel in the left front mudguard behind the headlight which had rusted out, and Kerry replaced this with one from a donor parts Citroën GS in his yard. He also noted a substantial difference in the construction methods used between a standard GS and the Birotor body shell, which was quite strongly engineered.

“All the front of a standard GS is bolted in — the Birotor is welded in. The part we wanted would go straight in, and the engineer said to weld it in. We got it finished during December of 2019, and I couldn’t get it in until the middle of January to get rechecked, but they kept just knocking me back every time it went in.”

TUNE-UP TIME

For anyone who has owned a two-stroke–powered car or motorcycle, the following procedure adopted by Kerry could be amusingly familiar.

“It really had become a bit of a nightmare, but I thought we were finally getting there. I had new locally machined brake discs and pads fitted. Then they hit me for emissions. I told them they had no emission (no comparison test) reading on it. But they could see the fumes coming out.”

With little open-road running, and with a separate oil pump feeding the induction system fitted on these engines, it was inevitable the Birotor would oil up with light use. By this time, a more than frustrated Kerry had an answer.

“I was so wild because every time I took it in, it had to go on a trailer, so I brought it home, put the British number plates back on the thing, and drove it from Beachlands to Manukau, and I just caned it before taking it back in. He wanted to know how I had fixed the emissions and I said I just adjusted the carburettor.”

There was one final twist.

“This is the stupidity of it. Every time it went back for a recheck on, say, two items, they would do the whole car again. I asked him why, and he said in case I had changed something else. Now it had passed, and there was just the paperwork to do. He told me ‘No. I’ve got to have a weigh.’ I said it was 1300kg as it says in the hand-book. No, he wanted it weighed.”

Kerry aimed to drive the Birotor to the Citroën Nationals in Hawera in March 2020, and time was running out to get it finished in time

“By this time, it was late February. Because I had a trucking company and know a lot of people, I shot across the road to Pink Bins’ weighbridge, and I told the guy there what I wanted, and he weighed it. I gave the tester the docket, and he wanted to know how I had got it done so quickly. Right at 4.30pm, he said I could now register it.”

At last he bought it home and attached its New Zealand number plates, and the following weekend it was off to a Citroën club meeting in Hawera.

“Dave Jones told me to put it on a trailer and trailer it down, but I didn’t want to do that. I drove it to Hawera and then drove it home. It didn’t run very nicely, and I had a few issues as it surged and hunted, and it wouldn’t run properly under 3,000rpm. We can’t drive these cars where they are supposed to be in New Zealand. It’s got to be doing over 4000 or 5000rpm, which is excellent.”

SURPRISE HELP

In an attempt to get things running smoothly, Kerry decided to investigate the rough-running problem, not easy when nearly all of his service material was in French or Dutch!

“Dave Jones was very good on a lot of the Citroën SM style control systems, which are the same.”

A faulty fuel pump shut-off solenoid was found, and one idle solenoid wasn’t working. One of Kerry’s contacts in Europe got him to pull the jets out of the carburettor, and he asked for the numbers on various parts.

“He said to me those dual restrictors are the incorrect number for this engine. Where do I get some? I scouted around for some here, and I couldn’t get any Solex carburettor bits. It’s a massive thing. It’s two carburettors in one, so I sent a message over to Europe and didn’t get a reply. Next thing, four correct jets turn up in the mail. I contacted my guy in Europe and said, ‘I’ve got the jets you sent me, and how much do I owe you for them.’ He said, ‘No, no, because you are a friend.’ Incredible!”

Since then, little tweaks, such as increasing the size of the fuel filter, has seen the Birotor running smoothly. Kerry has also learnt that at some stage a specialist firm in Belgium had retro-fitted ceramic rotor seals, extending the life of the engine considerably.

“I had it out at the Citroën Car Club (Auckland) Christmas function. It’s a nice car, and I like driving it. It was set up for left-hand drive, so the suspension is set up differently for our roads. I found the sway bar was sitting high on the left and low on the right, so I’ve adjusted it the opposite way around — and what a difference. Fitting wider 175 section tyres on it instead of 145s like the standard GS has also made a big difference.”

A REAL WHODUNNIT

While all the work was going to get the Citroën mobile, Kerry was also busy tracking down the history of his car.

“Now this car is totally original, and it sat in a shed in the dry in the south of France for 37 years. I’ve been trying to track some history, and it had a French number plate on it. The number was painted onto the car, and I asked them in Europe where this was from. The answer came back that it was a temporary number plate only fitted when the car was new before the owner buys it — so it had a dealer plate on it. Probably someone in the trade or a dealer, they said.”

Back when these cars were sold, it was normal for dealers to either own them or sell them to employees. Its background got more involved.

“I found that this car was supplied by Citroën to a Citroën dealer in the south of France as his stock, then he got a message to say that they wanted it back. Apparently, he said to one of his sales staff, if Citroën wanted this car back they were not getting it. They were up to something, the dealer thought, and he took it home and that’s where it sat for those years.”

Eventually the car was sold, and Kerry’s contacts tried to find out what happened to it.

“They did give me confirmation that it was registered in Belgium. Someone got it running in Belgium, and then it was registered in Holland. There’s a Facebook page called Citroën Birotor, which I’ve joined. There was a guy on there that I told this was now the third country this car was registered in. He replied to me that it was number five!”

Kerry’s car now appears to have been registered in France, Belgium, Holland, England, and now New Zealand.

“I bought it in the UK off a Dutchman. It had been for sale for a little while and, as I say, it was totally original. It’s never been repainted, never had any trim or anything done, but it had been knocked around underneath a bit. It had hit the ground a few times somewhere, and it had obviously been given a pretty hard time.”

MATCHING THE PARTS

Although called a GS, the only things interchangeable between the standard GS and a Birotor GS are the four doors, bonnet, and boot lid. The front guards are different as are the rear guards.

“The whole car is constructed so differently, and it’s so heavy underneath. It has chassis rails actually rolled to the floor pan underneath and the main chassis at the front is at the top of the mudguards. They couldn’t fit them under the engine as with the GS flat-four engine, so the rotary engine is hanging from the top. It has a three-speed C-Matic transmission, then the differential, which is pretty massive, and that unit belongs to a Citroën CX. The technology in this car for the ’70s is incredible.”

One major difference between a GS and the Birotor was the brakes. Usually mounted inboard at the front next to the differential in a normal GS, the disc brakes were now ventilated on a Birotor and fitted out near the end of the driveshafts.

A PASSION FOR THE CHEVRON

“I was always a Citroën fan as a teenager. My old man came home with a pink Citroën ID19 he had bought off [the agent] Stu Cranston in Tauranga. We were teenagers, and we wouldn’t ride in a pink car! He had that car for a quite a while.”

Kerry was about to go on his big OE in 1971 and worked as a technician for Tauranga Motors, the Triumph and Massey-Fergusson dealer.

His intention was to buy a Dolomite Sprint on his OE, but then Stu Cranston phoned his parents and asked if he was around, as he knew Kerry was about to leave and wasn’t working. Stu wanted Kerry to go with him to Palmerston North to drive a new car back to Tauranga.

“Stu said, ‘See that white one over there. That’s the latest Citroën GS.’ He said, ‘You can take that back.’ I couldn’t believe the little thing. It was just so good. I ended up buying one in France brand new and brought it back to New Zealand. While I was away, my old man had bought a Citroën DS23 EFI.”

Kerry then bought a Citroën ZX, followed by a Citroën C4, bought after a trip to France in 2008. He later added a DS3, then a Citroën Aircross. A 1973 GS was purchased in 2010, and Kerry rebuilt all the panel work. The GS was used in a tour around Australia in 2015, clocking up some 25,000km in two-and-half months with no issues.

“I admit I was a bit scared of the Birotor when I first got it. It is a nice car to drive, and I enjoy it. I think there are now only about 40 running on the road in the world in 15 countries. In Australia, one was built there as a right-hand drive one from new, which is unusual. New cars couldn’t be registered if they were left-hand drive. Except for the last five cars which were blue, all Birotors are all various combinations of the brown colours on mine or they are one brown colour.”

Kerry has always liked the unusual little Citroën and can now enjoy a rare slice of French motoring history. One of the very few modifications he has made to this intriguing and valuable little car was installing a remote GPS activated disabler.

Just arrived is a new chassis from Belgium for his 2CV project he has underway.

“You’ve always got to have something to do and keep yourself busy, haven’t you?”

Kerry never did get his Citroën Birotor to the National Rally in Wellington in March 2021. It was cancelled due to the Covid-19 restrictions. He hopes to get to the next one.

CITROËN GS, BIROTOR

Engine: Iron-housing, water-cooled, two-rotor 1990cc Wankel rotary engine, with twin choke, Solex carburettor

Max power: 107bhp (80kW) @ 6500rpm

Max torque: 101lb·ft (136Nm) @ 3000rpm

Transmission: Three-speed semi-auto, FWD ‘Citromatic’

Suspension: Independent front with wishbones; rear trailing arms; hydropneumatic spheres, self-levelling front and rear

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: Four-wheel power-assisted discs, ventilated at front, solid rear

Length: 13ft 6 ¼ in (4120mm)

Width: 5ft 4 ¾ in (1644mm)

Height: 4ft 6in (1370mm)

Wheelbase: 8ft 3 ¼ in (2522mm)

Weight: 2,844Ib (1290kg)

Performance: 0–60mph: 13.3 secs, top speed: 109mph (speed limited to 175kph)

Fuel consumption: 14.7mpg (16L / 100km), normal use. Hard use; 25L /100km (9.4mpg)

Numbers built: 1973–1975. Total: 847 units

Construction: Steel monocoque, five-door fastback, four-door fastback five-door estate, three-door van versions. GS: 1970–1979; GSA: 1980–1989. Birotor: Five-door hatchback

Price new: Birotor: GB £3,800. Estimated price now: £30,000 (Estimated NZ$58,000), 2019; Bonhams, 1974 model: sold for £27,750 (NZ$53,368), including premium