Allan Dippie’s TWR Rover 3500 SD1 Vitesse

By Ross MacKay

What price provenance? The online Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as: “The origin, or source of, or the history of ownership of a valued object or work of art or literature.”

In theory, any old backyard mechanic could have acquired one of the 280 2.6-litre six-cylinder-engined Rover SD1 automatics assembled at Motor Corp’s Nelson plant between August 1979 and December 1981 and swapped out the engine and trannie for a cheap 3.5-litre V8 from someone wrecking a Range Rover or Leyland P76. Fit a roll cage and some race car paint job, and you could have had a whole lot of fun for not a lot of money.

The real deal

This is not that. There are clues aplenty that this is in fact TWR/018, the genuine V8-engined Rover 3500 SD1 V8 Group A racer built in late 1985 / early 1986 by Tom Walkinshaw Racing in the UK. It was freshened up in Christchurch in the early 1990s by recently retired and relocated TWR engine guru Allan Scott. It is now owned and regularly raced here by keen Wanaka-based classic car owner and driver Allan Dippie.

Dippie is an active member of the largely South Island–based Historic Touring Cars of New Zealand group which, for the past few years, has been running the increasingly popular and well-supported Archibald’s Historic Touring Car Series.

With so many shells built into race (at least 19) and rally cars (as many as another 13), finding a pukka TWR car for sale has never really been a problem — in the UK.

British brutes

Here, the big British bruisers are now nearly as rare as unicorns, despite cooking versions of the sleek, five-door hatchback executive car selling in reasonable numbers here in period.

I well remember, for instance, being picked up at Christchurch Airport in the mid-1990s by the father of a mate of mine. I was delighted when he led us into the covered parking area to a menacing dark-coloured Rover 3500 SD1.

Despite having the air of a car out of its time, no longer in the first flush of youth, yet at the same time, not quite old or distinguished enough to be considered a classic, it was still impressive.

While I knew it was a late-model, five-speed manual V8 Vitesse, no less, with either BBS or Jaguar-style pepper-pot 15-inch mag wheels, I couldn’t help but agree with the car’s enthusiastic owner that the dark-chocolate brown colour that the two Whittaker’s Peanut Slab-sponsored cars TWR ran at the two Nissan-Mobil 500 meetings (at Wellington and Pukekohe) at the beginning of the 1986 season didn’t do the cars any favours!

But that was the extent of my knowledge at the time of SD1s, road, race, or otherwise.

As time passes, your memory decides which images are worth hanging onto. One of mine from the early days of Group A racing — 1984 or 1985 — is of a pair of Rover 3500 SD1s in the distinctive red-and-white Bastos (a Belgian cigarette brand) and Texaco livery of Dippie’s car, line astern, leading a round of the European Touring Car Championship.

Power plays

Looking through the prism of ‘light is right’, the two racing Rovers looked impossibly large, cumbersome beasts, even then.

What you have to keep in mind, however, is that when Tom Walkinshaw Racing took over the Rover 3500 SD1 racing programme from British Leyland’s own motorsport division in the early 1980s, TWR was also working — pretty much in parallel — with Jaguar on the even bigger V12-engined Jaguar XJS sports coupes.

What’s more, in the lead-up both to the introduction of Group A to the British Saloon Car Championship in 1983, and the locally conceived but sadly doomed FIA World Touring Car Championship, the competition consisted of BMW’s classic straight-six BMW 635 CSi or medium to large four-door ‘executive’ cars like Peugeot’s 505 turbo in France and, closer to home, Holden’s V8-engined Commodores.

The turbo cars that marked the second part of the Group A era, Volvo’s unlikely 240T and Ford’s Sierra were coming — fast — but were not quite there yet.

In this environment, the long, wide, sleek, and wind-cheating lines of Rover’s David Bache and Spen King–designed body, powered by the Austin-Rover group’s aluminium alloy V8 engine, meant that the Rover SD1 could well have been built with a parallel competition career in mind.

Before TWR came to the party, racing Rovers had been the typical modified production ones of the era, with rudimentary roll cages, upgraded production suspension and brakes components, and carburetted engines.

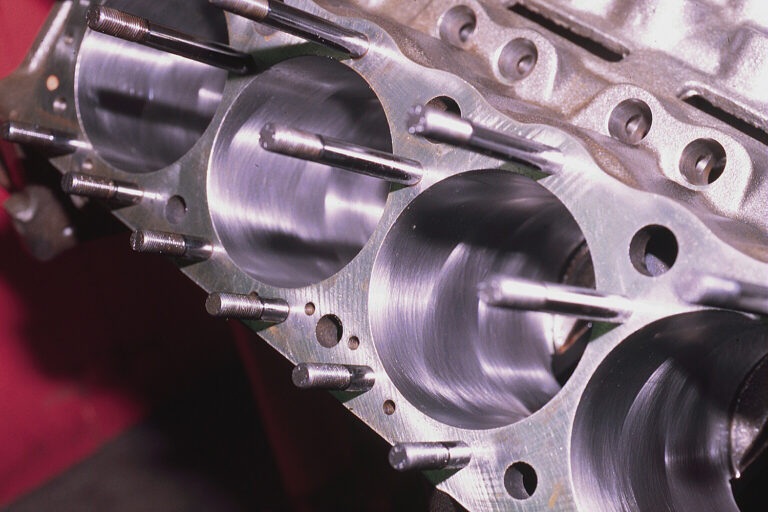

The TWR cars, on the other hand, were proper, dedicated racers from day one. Their special body shells in white were shipped from the factory to fabrication contractor Safety Devices where comprehensive eight-point roll cages were fitted. The shells were then delivered to TWR for assembly to begin.

Race on Sunday, buy on Monday

Though the Group A rules were drafted specifically to make sure that the cars that raced on Sunday looked just like the ones you could buy on Monday, a measure of freedom was allowed underneath.

And so cars like Allan Dippie’s TWR/118 of 1986 have unique suspension componentry front and rear, unique AP Racing disc brakes on each corner, a heavy-duty five-speed Getrag gearbox, and what I can only describe as super-sexy red Speedline centrelock 17-inch wheels.

In his book on the TWR Rovers, TWR and Rover’s SD1 — Inside Tom Walkinshaw’s Rover Racing Team, (see sidebar story) Alan Scott details the lengths TWR went to to sort out the way the Watts linkage–equipped live rear axle and limited-slip differential worked.

Scott also details the company’s move into electronic fuel injection and full digital engine function management with a fledgling Zytek company.

In its ultimate competition form, the 3532cc SD1 V8 engine produced in the vicinity of 253.5kW (340hp) — not a lot in today’s terms but more than enough to win races in period. And it is more than enough to keep Dippie focusing hard when contesting rounds of the Archibald’s Historic Touring Car series here.

That brings us neatly back to how he got to own one the most desirable cars of the early Group A era. The link is Allan Scott himself.

When Scott decided to retire from his job running TWR’s engine division in 1994, one of the souvenirs, or spoils-of-war, was TWR/018. He had shipped to his new home in Christchurch.

Fortunately for Allan Dippie, having got TWR/018 back to race condition back in Christchurch, Allan Scott got a bead on one of its sister cars, TWR/014. He was prepared to enter into negotiations to sell TWR/018 to free up the necessaries that would convince TWR/014’s long-term UK-based owner to part with it.

Provenance preferences

In the case of the two TWR Rovers, it’s their provenance that separates them. However, it is very much a case of ‘each to his own’.

Scott provides comprehensive appendices on every TWR Rover race and rally car built from TWR/01, which René Matge ran in the French Production Championship in 1983, to TWR/20, built for Neville Crichton’s South Pacific Racing squad to run in the 1986 European Touring Car Championship.

Though it was only run in the European Touring Car Championship for the one year, TWR/018 played host to a full complement of the team’s drivers. This included German ace Armin Hahne and Frenchman Jean-Louis Schlesser who ran it in the first three 500km races of the season, to Hahne and British Saloon — and later, Touring Car Championship — race winner Jeff Allum, who shared it at the fourth round of the series at Misano in Italy, and Hahne and Italian Gianfranco Brancatelli, who anchored the driving line-up at six of the other eight rounds.

Other drivers to slip behind the steering wheel to assist the TWR cause during the year included the team’s nominal number one, Win Percy, and our own 1967 World F1 champion, Denny Hulme.

Hulme actually shared his famous comeback win in the RAC Tourist Trophy race at Silverstone that year with Jeff Allum driving the white Istel-liveried TWR/014. That was one of the reasons Scott was prepared to sell TWR/018, but Hulme also drove TWR/018, to sixth place, no less, at that year’s Spa 24 Hour endurance race.

Allan Scott’s inside line

History records that Kiwi Allan Scott could hardly have arrived in Great Britain at a better time.

The year was 1979 and his specialist knowledge of rotary engines soon saw him in the employ of Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) the team which, at the time, was running a racing programme for Mazda GB and its rotary-engined RX-7s.

The team won the 1980 British Saloon Car Championship for Mazda using engines built and maintained by Scott. That prompted the ambitious and go-getting Walkinshaw to set up his own in-house engine building division and install Allan Scott to run it.

Between 1980 and 1994, Allan built the ‘division’ from what literally started as a one-man- band (himself) to a major enterprise in its own right. It played an absolutely key part in the multi-disciplinary motor racing business that TWR became.

Returning home to New Zealand with wife Karen and daughters Martina and Courtney, the Scotts settled in Christchurch and converted a stately home in Merivale into a boutique hotel (www.elmtreehouse.co.nz).

Allan has also turned author, as he was ideally placed to produce the definitive text: TWR and Rover’s SD1 — Inside Tom Walkinshaw’s Rover Racing Team. It was his second book in a series on his time working with Walkinshaw and his burgeoning team.

His first book, TWR and Jaguar’s XJS, and his third, TWR and Jaguar’s Prototype Sports Cars, make a trio of treasure troves for detail-hungry fans of the cars, the era they were built in, and the many people involved in the business of motor racing as it evolved through a period of massive technical, financial, and managerial change.

All three are available to purchase from Allan at [email protected].