Philip Parker’s meticulous restoration of a Series 2 Land Rover — the very best kind — delights everyone who sees it

By Ian Parkes, photography High Art Photography

If Helensville-born Philip Parker is right about this — and there’s no reason to think he isn’t — this is a sight we will see a lot more of: no-expense-spared, fully restored Land Rovers.

Since Jaguar Land Rover stopped making the Defender in 2016, ending a near 70-year run of the original recipe Land Rover, the value of these cars has continued to rise. The new 90 and 110 Land Rovers launched last year only really underscore the point. While they have interiors that pays tribute to the Land Rover’s utilitarian origins — trim fitted with exposed screw heads and so on — they are tricked out with every modern convenience so they will be equally at home battling the rugged terrain of Remuera as the manicured hinterland of Central Hawke’s Bay and Canterbury. In reality, they are much more of a tribute to the original Range Rover than the Landy. They even look a lot more like a Discovery than a Defender.

Certainly chemicals and fracking magnate Sir James Ratcliffe — whose Ineos organisation backed the UK America’s Cup challenge and who owns the Ineos Grenadiers cycling team (formerly Team Sky) — thinks Land Rover missed the mark with the new vehicle. It left a large enough gap in the market for him to create his own version of a heritage Land Rover in the upcoming Grenadier four-wheel drive.

But of course only the Land Rover is the original, and the growing affection for that classic vehicle currently knows no bounds. The recent visit to New Zealand of ‘Oxford’ gave some indication of the depth of the affection for them here. Oxford was one of the two Land Rovers that students from Oxford and Cambridge drove overland to Singapore in 1955, at one stroke establishing Land Rover’s global reputation as the expedition vehicle. Oxford attended several car shows here including the Ellerslie Car Show but it was much more on home turf at the Wheels at Wanaka event in April, as reported here last month.

The man who engineered the car’s visit here (also organiser of the time trial event for classic cars in the Targa New Zealand), Rod Corbett, decided to arrange a little safari through the South Island high country for Oxford in company with some local Land Rovers. He was overwhelmed by Land Rover enthusiasts wanting to come along. He had to cap entries at 80 vehicles per safari, and run three separate safaris to even begin to satisfy demand. Versions of every iteration of Land Rover took part, from a faithful reproduction of the very first road-registered Land Rover through to the new Land Rover 110.

Smash Hit

The very reason Rover decided to invent them in the first place, to create a four-wheel drive, go-anywhere vehicle that would be a boon to post-war farmers aiming to mechanise and increase production, made Land Rovers a smash hit with country cousin New Zealand, which was rapidly climbing the international prosperity rankings on the sheep’s back.

Certainly Philip, who has spent almost all of his life on farms, says for decades they were as central to his existence as gumboots. “We’ve always had Land Rovers: Series 2s and Series 3s. I feel a bit strange if I don’t have a Land Rover in my life,” he says.

So, he’s got the emotional attachment and a deep understanding of the affection and nostalgia that’s driving the current surge in interest, but he’s also making a hard-headed investment. He’s so convinced of the inexorable rise in the value of Land Rovers that he decided on a patient, open-cheque-book approach to restoring this Land Rover. “After $30,000, I stopped counting,” he says. “I always knew it was going to cost a reasonable amount, but the cost of anything was never going to present a barrier in the end.”

Restoring a Land Rover should be relatively straightforward, as the early ones in particular were deliberately pared back, simple machines and most spares are readily available — but you can’t take that for granted. Philip says he initially entrusted this vehicle to another workshop who had it for some time but he grew dissatisfied with their work. He talked it over with Brian Renall at Top of Range Automotive in Albany which does the servicing work on his Range Rover Sport and P38. They know Land Rovers inside out, and Brian took it on as his final project before handing the daily running of the business onto his son, Tyler.

Philip says his brief to Top of Range was to restore it to as-new, concours competition standard, which naturally calls for complete authenticity. They considered each element of the restoration as a project. The project took about three years, progressing when time and parts were available. “I didn’t push them on time. I took a very long-term approach. It’s an amazing inflation hedge.” Philip took great pleasure in the occasional discussions deciding whether to refurbish parts to as-new condition to maintain originality or whether it was to replace them.

Peter Rabbit Green

The canopy, for example, was a second-hand item they refurbished. The body colour was changed too. It was originally a dull grey, but Philip’s young cousins had immediately latched on to the green Land Rover in the new Peter Rabbit films and, as the colour certainly looked ‘right’ to Philip, green it would be. Most if not all Series I Land Rovers were painted one of three shades of military green, as in the immediate post-war years those ex-military paints were readily available.

The door shuts with a resounding clunk as the substantial brass tongue engages the striker plate. “I knew we were making progress when I heard that sound,” says Philip. Looking along the side of the Land Rover shows off the workmanship that has gone into this rebuild. Land Rovers were built with flat sheets of aluminium fastened to a full galvanised frame. Naturally, the frame on this Land Rover has been fully re-galvanised too. But unstressed flat sheets are very prone to distortion and wobbling in or out. That’s why the reflections on black Land Rovers don’t do them any favours. It’s to Top of Range’s credit that they bowed the guards outwards ever so slightly over the wheels, which gives them a much more uniform and stable shape. It looks just right.

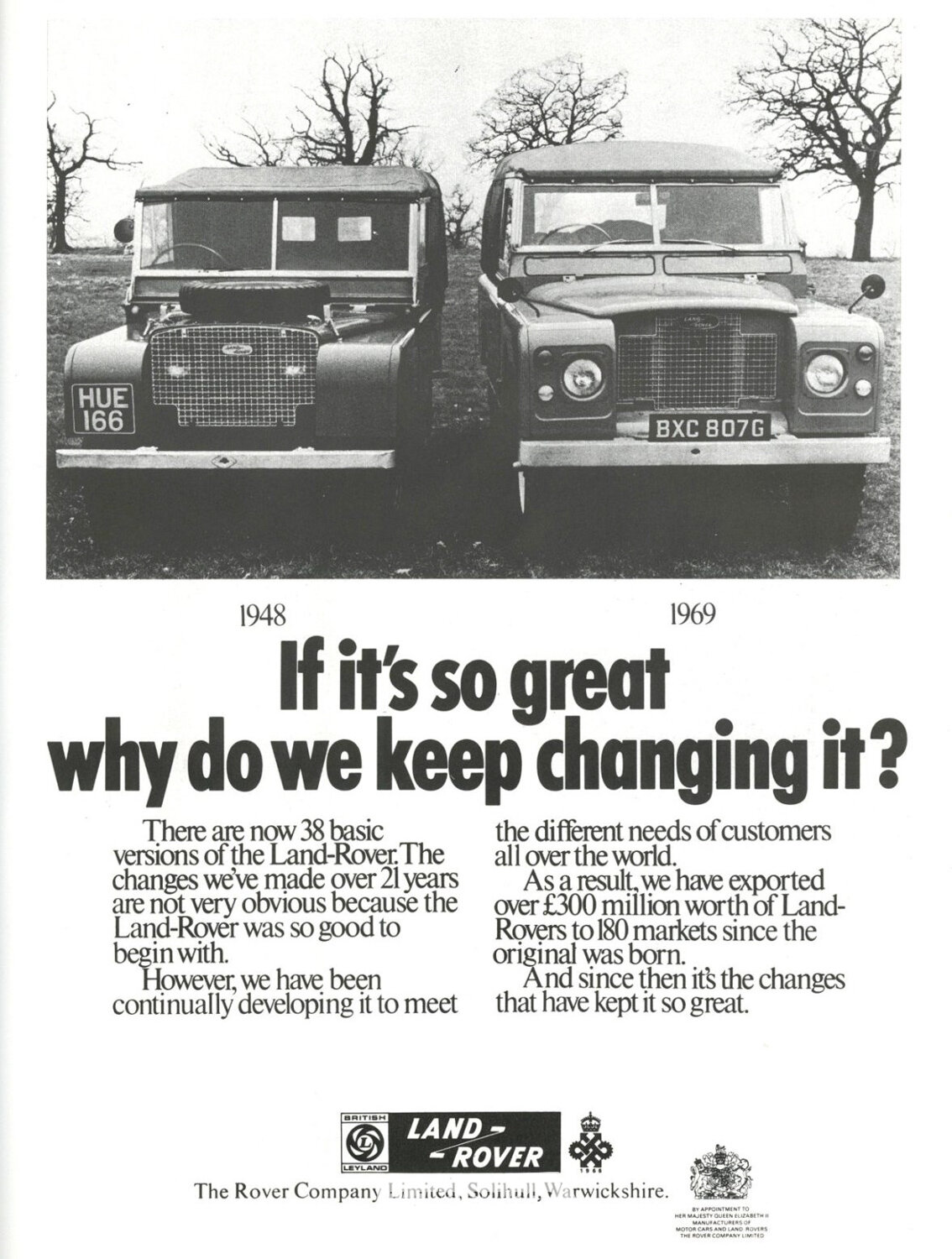

As Maurice Wilks and his team at Rover set about updating their original 1948 design, they were keenly aware Austin was gearing to take a slice of the action, especially in military contracts, and was working on its own four-wheel drive machine. The Rover team was determined the Land Rover should maintain its lead as the best four-by-four by far.

Styling Refined

The publicity won by the Oxford and Cambridge Trans-Africa Expedition, and their even more ambitious 1955 Far Eastern Expedition to Singapore, had established the car’s reputation and unique qualities around the world. That crystallised the design team’s brief for the next version. It should continue to be a military vehicle, an expedition vehicle, a vehicle to be used in the African bush and the Australian outback, where the ability to fix it in the field could be vital to survival.

Stylistically, the Series 2 was a much more refined and appealing but still rugged design. It introduced the distinctive small curved hip running the length of the body that became a defining feature of the ‘Series’ Land Rovers, so much so that when you notice it, the Series I vehicles look odd without it.

The Series 2 also retained the distinctive recessed radiator grille. Most still had the lights in that well too, although in 1968 on Land Rovers exported to America they moved to join the sidelights on the front wings to comply with American law. On early ‘Federal’ versions, they were quite prominent, earning the sobriquet ‘Bugeye’, but in 1969 the wing-mounted lights were set in a recessed panel. The final big style change, moving the recessed grille forward to create a flush front, occurred right at the end of the Series III’s reign with the launch of the first V8 Land Rover in 1979.

The Series 2a, introduced in 1961, is now considered the most durable and easily repairable series, and the version that Land Rover got most right. The letter suffix on the chassis number changed in line with upgrades but the series kept the 2a moniker until the Series 3, usually styled Series III, was introduced in 1971. That makes this 1971 Series 2a Land Rover one of the last of its kind.

The spartan look of the Series 2 is appreciated today for its own minimalist aesthetic qualities, but features like the bare-metal dash were deliberate choices. It meant the instruments were easily accessed by undoing just five bolts. Air conditioning was achieved by opening flaps under the windscreen — not much to go wrong there. And being able to do an engine overhaul while leaving the engine block in the vehicle was a significant advantage when out of town. The rear main oil seal could also be replaced without removing the engine or gearbox. The adaptability of the Land Rover platform — and let’s not forget it had power take-offs for driving other machinery — was a key element in it also being chosen for many first responder as well as agricultural and military roles.

The Series 2 was made in 88˝ (223cm) SWB or Short Wheelbase and 109˝ (276cm) LWB, Long Wheelbase, versions. The first SWB models were fitted with the Series I’s two-litre four until stocks ran out in 1958. After that, they all got the new 2.25-litre four-cylinder OHV engine, which produced 52kW (70bhp) at 4250rpm, a useful gain over the two-litre’s 38.7kW (52bhp).

Curved Shoulders

The axles were changed resulting in a wider track for the Series 2 at 1219mm, which is what prompted the addition of the curved shoulder, widening the body to suit. Rover stylist David Bache matched this with a curved-back cab for the utility version and curved sides to the roof and bonnet lip. Deeper body panels also hid more of the chassis, which gave the vehicle a much more civilised appearance.

Barely creditable today, but the four-speed manual gearbox only had synchromesh on the third and fourth gears. It took until 1972 before all four gears featured synchro. The cab also featured the simple and distinctive red and yellow floor-mounted knobs for engaging four-wheel drive and low- or high-range gears. Drivers had to stop the car to engage low range. It had front and rear differentials but no centre diff, so four-wheel drive could only be used on loose surfaces to avoid transmission wind-up. All four wheels had drum brakes, plus one on the transmission for the handbrake, but the long wheelbase model got larger drums front and rear. Front and rear suspension was by half-elliptic leaf springs with steering by recirculating ball and nut.

In 1966–1967, LWB models got the option of the Rover six-cylinder engine of 2625cc capacity from the Rover 100 saloon. This overhead inlet side exhaust engine produced 62kW (83bhp) at 4500rpm and torque of 173.5Nm (128lb/ft) at 1500rpm. It remained in production until the advent of the V8 in 1979. The IOE engine (inlet over exhaust) design used in both four and sixes was actually a more efficient design than it sounds. The angled head and piston produced a hemispherical combustion chamber which allows better fuel burn, and it gave a shallow gap between inlet valve and piston, which avoids knocking with low-grade fuel — especially useful given the Land Rover’s affinity for the road less travelled.

The Series 2 and 2a featured in the film Born Free, the TV series Daktari, and there’s no doubt it inspired many other follow-up African adventures, captured on celluloid or not. This was the Landy that made Land Rover a household name.

In 1972, Land Rover added the unburstable Salisbury diff and axle which solved a noted half-shaft vulnerability. While the Series 2 and Series III Land Rovers cemented the vehicle’s unique reputation globally — and the one million mark was surpassed early in the Series III’s reign — the zeal and initiative of the Wilks era was lost in later years and Land Rover, at one point, was lucky to survive.

Right Place, Right Time

Selecting this Land Rover for this rebirthing process was relatively straightforward for Philip. It was owned by his cousin, Des Paulsen, who is married to Philip’s PA. He had retired it from active service on his family’s Muriwai farm many years earlier. It had sat outside, slowly, organically, reuniting with the land it had served for years, until Philip persuaded him to part with it in part-exchange for some work Philip had done on a sub-division. His promise to restore it secured the deal.

Philip says it was in well and truly used condition, but it had done relatively few miles at around 130,000 for its 1971 vintage (the last year of the 2as). Even more remarkably, Philip has known all of its private owners, who lived and worked in a small geographical circle in the North Auckland area. That provenance really only adds to its charm.

It was sold in 1971 to DSIR for their geological survey team. Then it went to the Post Office in Dunedin in 1980. They kept it for three years until Henderson Ford specialist Eli Friedlander’s Forward Specialities bought it at 88,000 miles. Philip went to school with his daughter. Then Brian Bracey, Philip’s grandparents’ neighbour in Huapai, bought it in 1984. And cousin Des bought it from them at 100,557 miles in 1987.

“He was genuinely shocked when he saw it again,” says Philip.

There are two features on this Land Rover that might raise the eyebrows of Series 2 aficionados. The first is the seats. They are the more sculpted and comfortable models from the Series III Land Rover. However, a set of seats from the Series 2 are under construction so they can be installed for shows or competition if required. The second feature is the overdrive. Philip says these handy units weren’t offered as standard but were developed later and made available as an aftermarket fitting. Relatively few were fitted to farm-based Land Rovers, which was the case for most of the Series 2 vintage vehicles, but Philip considers it a most worthwhile addition. “It will cruise comfortably, completely unstressed, at 80kmh.” Without it, he reckons you would either be pushing it out of its comfort zone, or be down at 70kph, which would be much more of a nuisance to other motorists.

The four-cylinder engine is actually much quieter and smoother running than I’d anticipated, given the blame these two-litre petrol engines had heaped on them for Land Rover ceding its crown to Land Cruiser — but this was now virtually a new engine. While they were designed and built to be refurbished in the field they were actually pretty strong and reliable, just not as powerful or as long-legged as farmers at this end of the earth, especially in Australia and South Africa, really wanted — which they could get in the Land Cruiser and Nissan Patrol.

From an Anglesea Beach to the World

If the Land Rover’s profile looks like a kid’s drawing of a car — if less so than Tesla’s Cybertruck — that’s because it was first drawn in the sand with a stick.

The artist, though, was no child. Maurice Wilks was a talented engineer developing Rover’s gas turbine powered car, following on from his wartime work with Frank Whittle on his revolutionary jet engine.

Rover had asked Wilks to come up with a utility vehicle as a stop-gap project. The company was struggling to sell its luxury cars in a near destitute post-war Britain. Maurice had the American Jeep in mind, and in fact the prototype was built on a Jeep chassis, but with the future of the company on the line he and his engineer brother, Spencer, put their minds to coming up with something a whole lot better.

Wilks sketched out his original idea for this 4×4 Rover on the sandy beach near his farm on the island of Anglesey. Launched in 1948 the ‘Land-Rover’ was an instant success. Sales of the Land Rover soon outstripped sales of Rover luxury cars by a margin of two to one. It quickly found favour with farmers in the UK and wherever the asphalt ended in the far-flung reaches of the Commonwealth.

Sales reached more than a million part way through the Series III Land Rover’s reign but by then sales volumes were in serious decline. At that stage Land Rover was part of the beleaguered British Leyland. That company’s inability or unwillingness to invest in new powerplants that would give the Landy a decent on-road cruising speed — so vital in places like Australia and South Africa — meant Land Rover began losing sales hand over fist to more powerful and roadworthy vehicles from Japan; Toyota’s Land Cruiser and Nissan’s Patrol.

The advent of the Range Rover, changes of ownership to BMW and later Tatra — and finally, some decent powerplants — plus a healthy dose of carefully nurtured affection for the car’s literally ground-breaking history, saw the marque saved. The Defender, the last iteration of the Wilks lineage, ceased production in 2016.

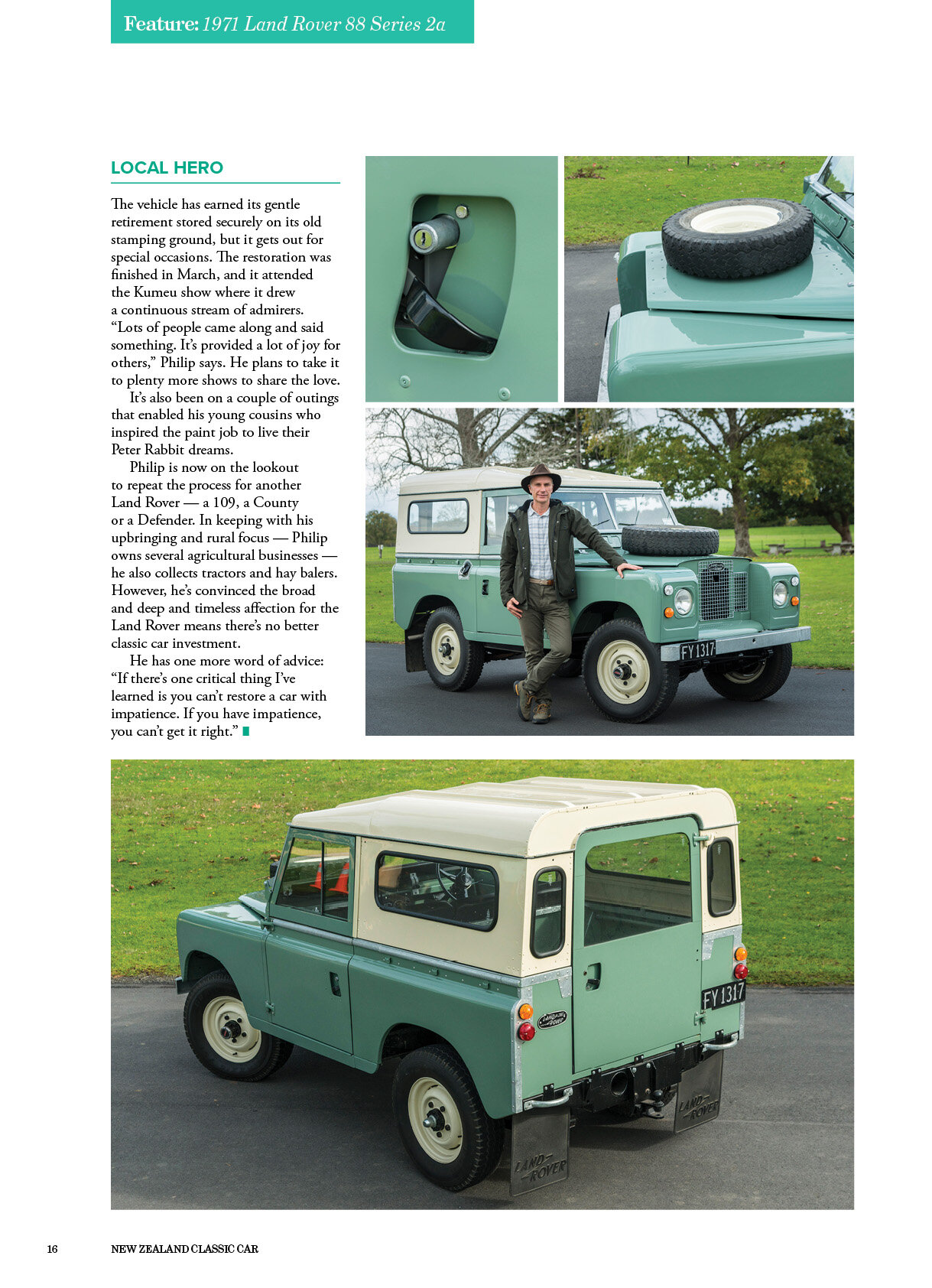

Local Hero

The vehicle has earned its gentle retirement stored securely on its old stamping ground, but it gets out for special occasions. The restoration was finished in March, and it attended the Kumeu show where it drew a continuous stream of admirers. “Lots of people came along and said something. It’s provided a lot of joy for others,” Philip says. He plans to take it to plenty more shows to share the love.

It’s also been on a couple of outings that enabled his young cousins who inspired the paint job to live their Peter Rabbit dreams.

Philip is now on the lookout to repeat the process for another Land Rover — a 109, a County or a Defender. In keeping with his upbringing and rural focus — Philip owns several agricultural businesses — he also collects tractors and hay balers. However, he’s convinced the broad and deep and timeless affection for the Land Rover means there’s no better classic car investment.

He has one more word of advice: “If there’s one critical thing I’ve learned is you can’t restore a car with impatience. If you have impatience, you can’t get it right.”

Printing error

As you may know, this story was printed in issue 367 of New Zealand Classic Car but the last page was missing. A compilation error, which occurred when we re-uploaded the file to the printer after correcting a different glitch, meant the final page of the Land Rover story was missing. In its place was a page from the following story. It was an excruciating error and we humbly apologise to our magazine readers.

One of our readers suggested putting the missing page on the website, so those with the magazine could slip it into the issue in the right place, if they wanted to. Nice idea, so here it is, available to download and print.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 367