Lotus and Ford made many happy memories together. Michael Clark recounts some of them through the eyes of various Kiwi motor sport greats

By Michael Clark

In September 1970, Jochen Rindt was killed at Monza. The German-born Austrian was leading the title chase and, with only three rounds of the world championship remaining, there was a very real prospect of Formula 1 (F1) having a posthumous champion. Lotus elevated a young Brazilian into the frontline to replace Rindt. He won the US Grand Prix (GP), grabbing headlines, which spoke of the 23-year-old, who was competing in lowly Formula Ford just a year earlier, now winning at the highest echelon. A star was born. Yet, when Emerson Fittipaldi was crowned world champion two years later, another hotshot had already arrived, in the form of South African Jody Scheckter — and his rise from FF to F1 had been even more rapid that the Brazilian’s.

Yet neither, nor anyone else before or since, had achieved what Aucklander David Oxton did in January 1971. At the New Zealand Grand Prix (NZGP) meeting 50 years ago, Oxton raced a contemporary F1 car and a Formula Ford at the same meeting. Only a couple of days prior to the event, David had no idea he would be driving the March 701, which was less than one year old. It took another half-century (as he helped with the background for this story) for him to realize it was the same car that Mario Andretti had used in the 1970 World Championship.

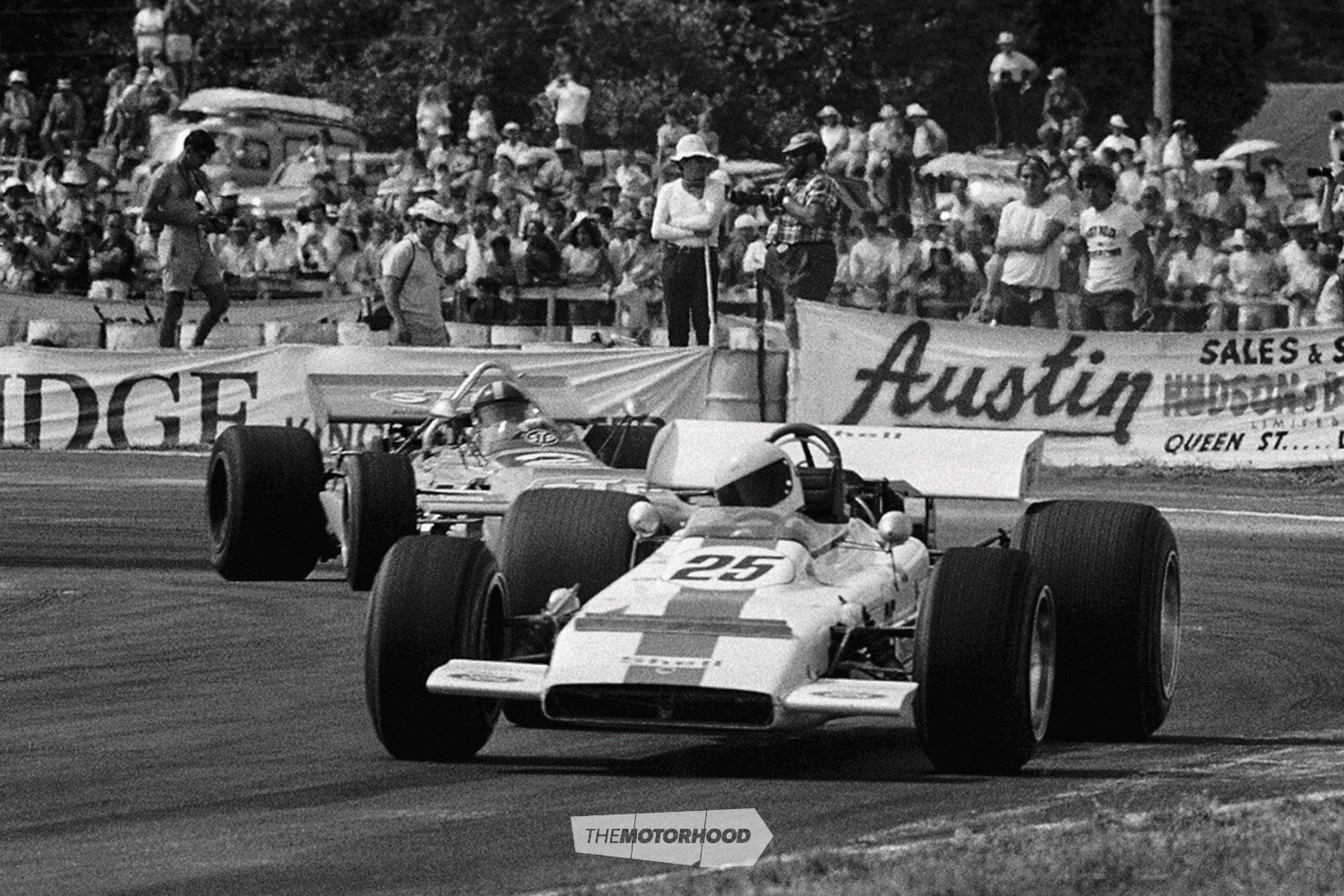

Levin 1971: Oxton leads Amon. A week later they’d swapped cars…

The tale has its origins in the first two months of 1970, when Oxton and his father Steve realized that there was nothing around to buy or lease for the summer series.

5000s and Atlantics

Formula 5000 (F5000) and Atlantic had arrived and David ended up working as a gofer for American Mike Goth. Oxo instantly formed a bond with team mechanics Bruce Burness and Joe Cavaglieri, who would spend the rest of 1970 tending to the new Ford-powered Lotus 70 in the North American championship. The final round was in Florida in late October. David takes up the story: “The team had decided to run their spare car and, based on nothing more than seeing me, helmetless, doing some shakedown laps in Goth’s car, Bruce and Joe suggested me for the drive. The call came completely out of the blue, and so I found myself flying to America for the first time, and then Joe and I drove all the way from LA to Sebring.” David was 24 and I was intrigued to discover if his super-supportive parents saw this as potentially the start of a F1 career. “Well,” he says, “I was only about half as good as Dad thought I was …” But there was every reason to be optimistic: in an unfamiliar car, at a circuit he’d never previously seen, he finished fourth in a field of 24.

“After the race, there was a banquet and somehow the Lotus guy present got on the microphone and announced that their new Kiwi driver would be doing British F3 [Formula 3] for Lotus next year,” he says. That was the first David had heard of it. And it wasn’t the last time Mike Warner made a statement to him that was never kept. “He said they were sending the Lotus 70 to Warwick Farm for Dave Walker to race in the Australian GP and could I run the operation? I said I could so I enlisted [future F5000 star] Jim Murdoch. We flew to Sydney with Jim’s toolbox as luggage, hired a station wagon, organized a trailer, etc. [on the understanding] that Lotus would cover all expenses.” Half a century later, David is still awaiting payment.

Walker was fifth at Warwick Farm and then, in an arrangement involving Steel Brothers, the New Zealand Lotus agents, the quasi-works Lotus was offered to David for the New Zealand rounds of the Tasman Championship.

January 1981: Dave McMillan acknowledges the crowd after winning the New Zealand Grand Prix at Pukekohe

Bone-breaker

At the time, Chev’s five-litre small block was proving to be the weapon of choice in the initial years of F5000. Ford’s V8, while perfectly competitive in the front of a Trans-Am Mustang, was an unloved alternative in F5000. However, engine-building legend Ryan Falconer was sufficiently impressed with the Kiwi at Sebring to offer him one of his special Boss V8s, but it came with a warning from the mild-mannered American: “‘David, you just make sure the engine comes back to me in the same condition — otherwise, I will come down to New Zealand and break every bone in your body’ … He was a lovely man.”

Oxton hustling the Ford-V8 powered Lotus 70 at Levin

David spent most of the opening round of the 1971 Tasman Championship at Levin on 2 January, engaging in battles involving the 2.5-litre March 701 of Chris Amon. Having spent 1970 at the wheel of the works March in F1, Chris had agreed to drive the STP-sponsored car owned by the powerful Granatelli family, despite its handicap. The three-litre F1 Cosworth DFV had to be de-stroked 500cc to race with the five-litre V8s for the Tasman. Chris eventually finished third, with David fourth, but was well behind the McLaren M10Bs of race winner Graham ‘unbeatable at Levin’ McRae and Australian Niel Allen.

In the days that followed, a deal was struck whereby Vince, son of Andy, Granatelli purchased the Lotus 70 for Amon. This was accompanied by a swift livery change from white and blue to STP red. David ended up with the March. “I guess I was happy just to be driving anything half decent,” he says. He qualified right behind Chris in ninth, while the front few rows were dominated by McLarens. “I’ll always claim that a helicopter upset the aerodynamics going into turn one and put me off,” he says, “but eventually a half-shaft broke and put me out.”

World first

Earlier in the day, David had been forced to start from the back of the grid in the Centenary of Auckland Formula C race for FFs, and it is by virtue of winning that race, albeit fortuitously when Peter Hughes retired after dominating proceedings, that the unique achievement of racing an F1 car and FF on the same day, was sealed. The Boss 302 dropped a valve in practice for Wigram. David assured me that fortunately the bone-breaking threat of the Falconer was ameliorated once the Granatellis took ownership, and so the March was annexed for Chris as David did his first TV commentary. David got back in the March for the last time at Teretonga, qualifying mid pack before enduring a forgettable race day with gearbox issues that caused a late race spin that meant he’d finish just out of the points.

“The decision was made to just focus on the Lotus in Australia and, for reasons I’ve never understood, I was taken over as part of the team. It clearly wasn’t to be a spare driver because, when Chris became unavailable for the final round, they put [current American F5000 champion] John Cannon in the car,” David says. But the fun and games weren’t over. Before the series commenced, David’s dad had been commissioned by the Granatellis to organize a truck through Avis: “When the cars were loaded in Christchurch, Vince loaded the truck as well. Dad got a call from the Avis guy to find out where the truck was and was utterly speechless when he was told ‘somewhere between Sydney and Brisbane’. That was typical of Vince. As far he was concerned, New Zealand and Australia were the same thing.”

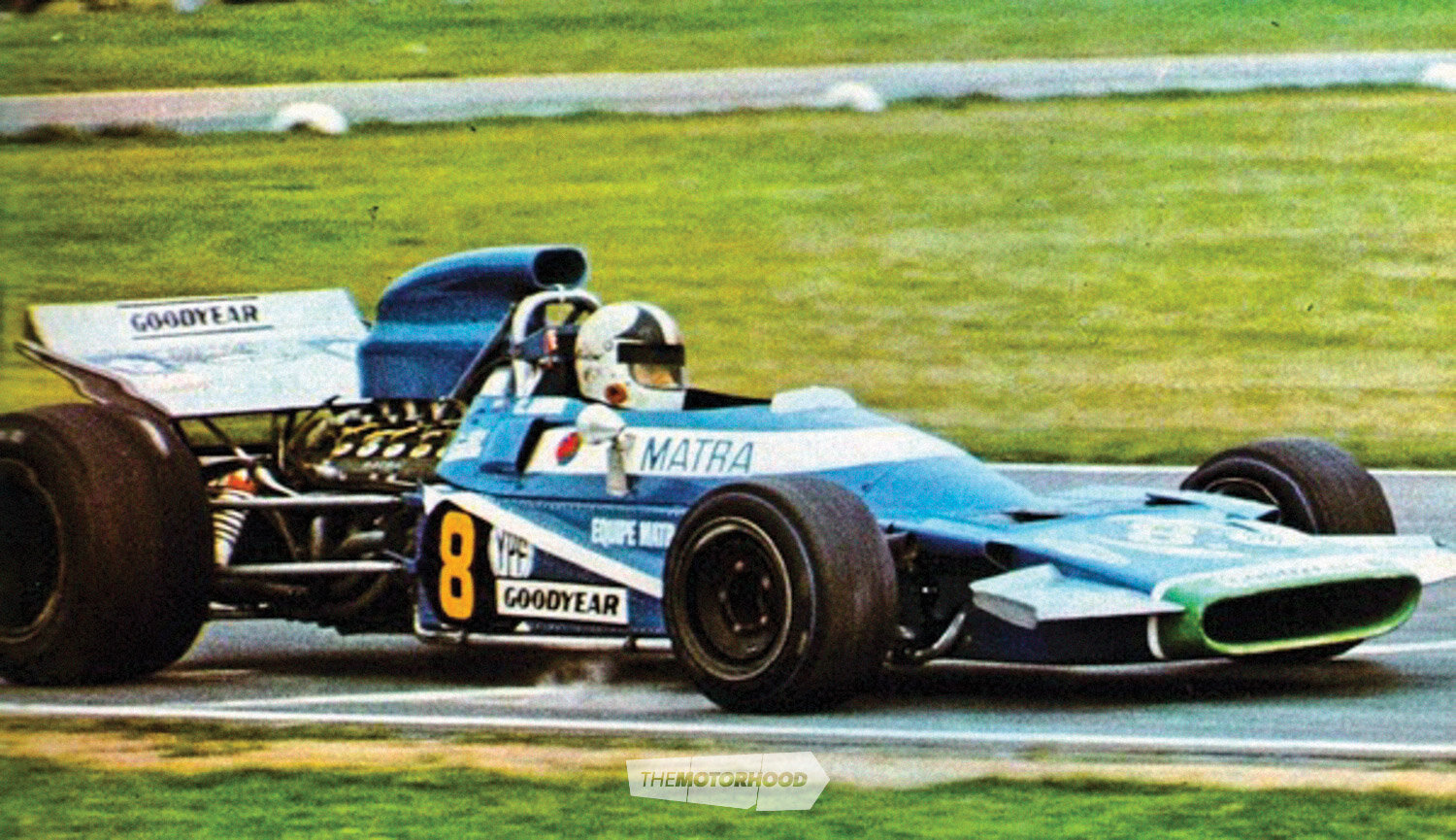

Amon’s first for Matra

Chris Amon missed the Teretonga round of the 1971 Tasman so that he could compete in the Argentinean GP for his new F1 team, Matra. In years to come he would often sum up the similarities of his three years at Ferrari and then two with the French missile manufacturer: “Wonderfully balanced, good-handling cars with beautiful-sounding V12s — that never had enough power.” His retainer from Matra was probably the largest in F1 50 years ago, and he headed off to Argentina with cautious optimism. “That chassis was a real joy after the March.” In the first of the two heats, “I managed to battle my way up to third or fourth, but I was so short of power.” In the second, “I must have passed about six or seven people … got in the lead and disappeared.”

Just as he’d done in his first race for the Scuderia, when he and Lorenzo Bandini won the 24 Hours of Daytona five years earlier, Chris won his first race for Matra, 50 years ago, on 24 January. And just as with Ferrari, that first-up win was just the start of a period of false promise and frustration.

In 1982, Dave McMillan was North American Formula Atlantic champion in this Ralt RT4

A rare colour shot of Chris Amon winning on debut for Matra — Argentina, January 1971

Swifty

Terry Marshall’s 1971 Tasman shot graced the cover of Michael Clark’s 1971 book

Dave McMillan always optimized his car’s bodywork with sponsors’ decals. Year after year, he introduced new companies to motor racing, as he topped up the budget after spending the northern summer in the States, sometimes racing but mostly working on other people’s cars. As a youngster here, he cut his teeth for fellow Hamiltonian stars Jim Palmer and Graeme Lawrence, but once armed with a Formula Ford himself he was instantly a contender. Dave was twice New Zealand champion before we adopted Formula Atlantic and so began his long association with Ralts. He was quick everywhere, and at Wigram in 1979 I watched him bury the opposition with a masterclass display in both heats. However, it was 40 years ago this month that he claimed the biggest prize of all — the NZGP.

Among his support crew that day was former New Zealand sportscar champion and F5000 star Gary Pedersen, who recalls how tightly the budget had to be managed: “There was no money in his background, so he had to work for every cent. He was great at looking after his sponsors and most stayed with him for year after year.” McMillan was a late starter and already 36 when he won the GP at Pukekohe, so any chance of F1 had gone, but in 1982, with the support of his Kiwi mates, he had a tilt at the North American Formula Atlantic Championship. “We were on the proverbial shoestring — all of us sharing one motel unit to save money,” says Pedersen. It paid off and Dave ‘Swifty’ McMillan added that title to the three Gold Stars back home. As Gary says, “He was a battler — superb at setting a car up just right, and a damn quick driver.”

Dave has been based in the States for years, but if our paths ever cross I’d love to do ‘Lunch with … ’ him.

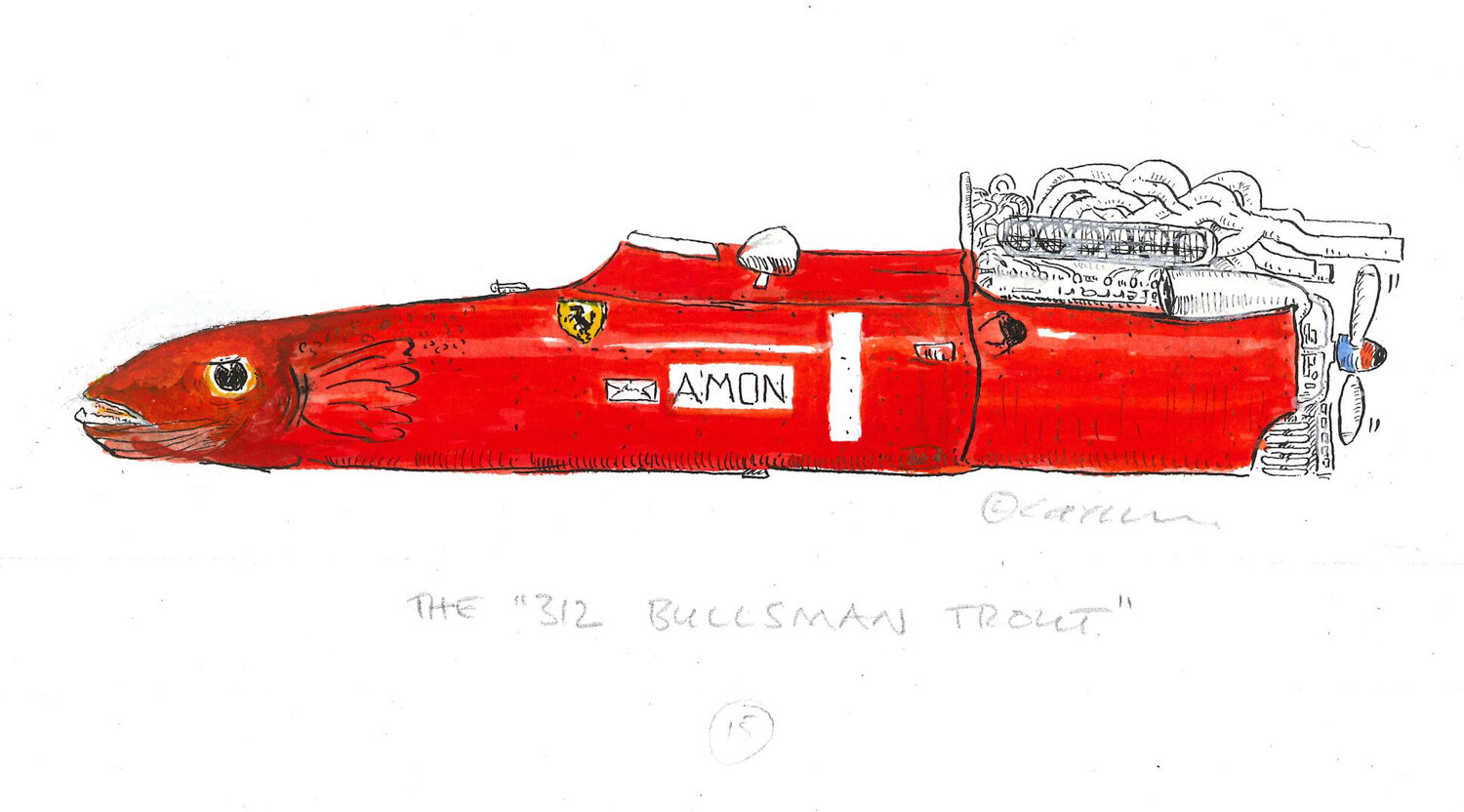

Fishy racing cars

The book based on the cartoons of Jay Cassells is out, and I can confirm that the text is as witty as I’d expected it would be. Reconfiguring old racing cars into fish isn’t as weird as you might think once you look closer at cars in profile. After all, Ferrari’s dominant 1961 championship-winning car was nicknamed the ‘Sharknose’. Jay is a lifelong lover of motor racing and has intertwined aquatic-based themes into the story on each car — it’s great fun. For a copy, contact him on jakehassells.com.

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 361