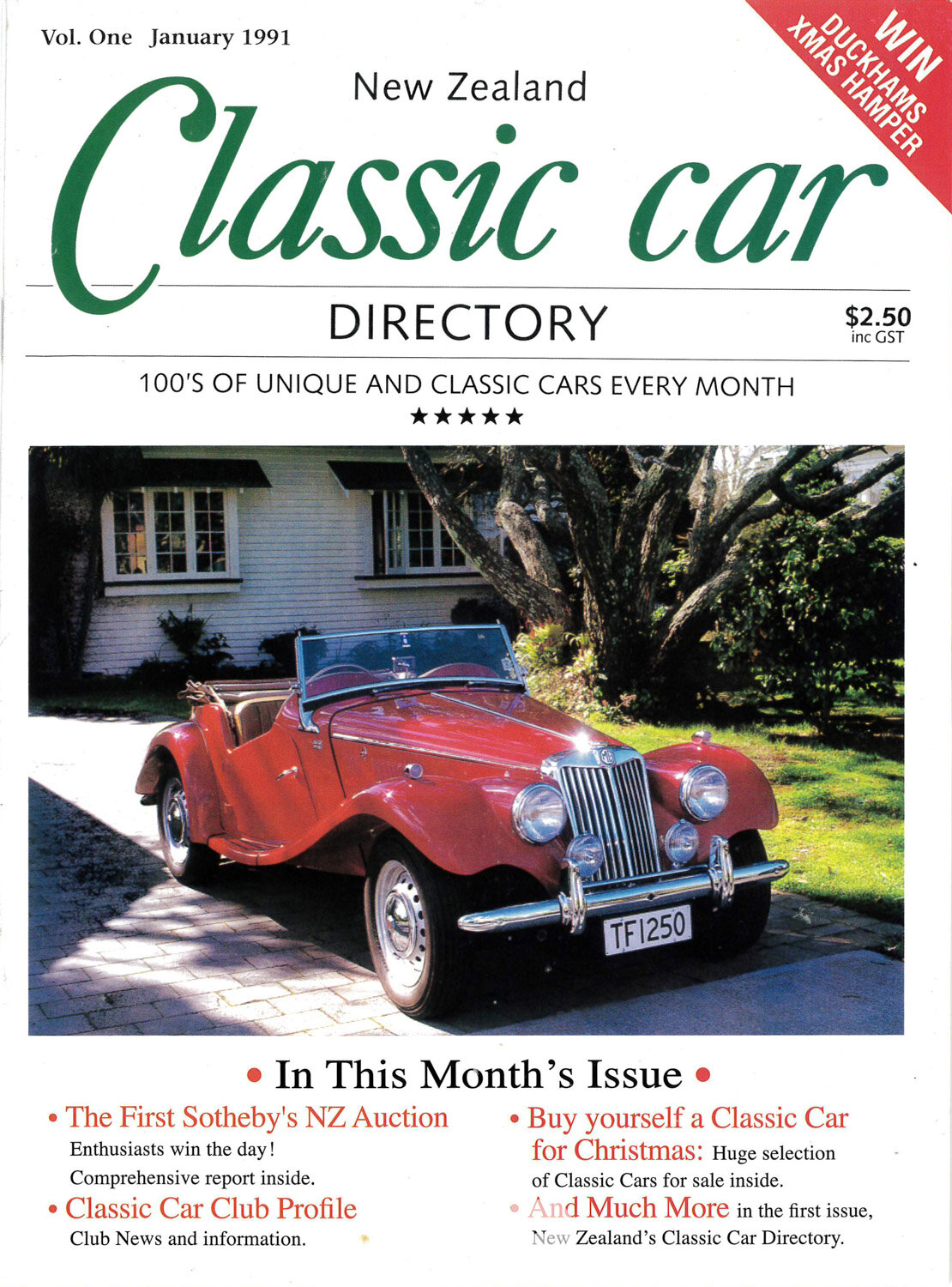

Founder and publisher of New Zealand Classic Car Greg Vincent almost fell into the publishing game. He helped create New Zealand’s vibrant classic car scene almost by accident

By Ian Parkes

Greg credits his success to the fact that he didn’t have a background in either journalism or, strictly speaking, classic cars. He says those who did know about those things almost uniformly said a magazine wouldn’t work.

“I just didn’t know any better,” says Greg, “and I kept going.”

A friend he had made while working in London was working in publishing in Australia. Greg picked his brains, asking him what he needed to do to pull a magazine together.

“He told me I needed someone to put it in the shops, so I looked that up in the Yellow Pages. I sorted that, then called him up again and said, ‘What’s next?’

“He said, ‘OK, you need a printer.’

“‘What sort of printer?’

“So he told me. I did that and said, ‘What’s next?’”

Greg said his friend fully expected him to give up, but kept giving him the next step as Greg ticked each one off.

The friend told Greg he’d need a designer — to make words on a page — and an editor. He found a magazine designer who could operate the new Macintosh computer using some software thing called ‘Pagemaker’. Greg then put an ad in the paper seeking an editor. He found one of them too, but after the first issue was printed the editor gave him a bill for thousands.

“It was way more than the printing! I thought, OK, I can’t afford this. I’m going to have to do this myself,” Greg says.

Greg got stuck in and learned the craft and the publishing business on the job. He had come back to New Zealand determined to start his own business. He just hadn’t known at the time what it would be. He asked a friend, a successful business owner in the US, to give him a steer. She gave Greg the best advice he had ever received.

“She said, ‘Do something you enjoy, and you’ll make a success of it.’”

The former Grey Lynn coffin factory where Classic Car started

Starr turn

Before returning to New Zealand in 1991, Greg, an Avondale-born boy, had been a sound engineer working in London at Mag Masters studio in Soho. He said the money was good in the heyday of the ’80s, making 30-second commercials that could cost anything from £60K to £500K, but eventually Greg became disillusioned with the vulgar wastefulness of it all. Not that he didn’t have good times. He worked on the Thomas the Tank Engine animation series. Ringo Starr did the voiceover. He and other stars of the era were a common sight in the studio and on the street.

Greg recalled when American singer Harry Nilsson came in with Ringo to record a new voiceover for Nilsson’s film The Point, originally recorded by Dustin Hoffman. Harry and Ringo got slowly smashed in the studio on whisky and cocaine — nothing for the crew — and they were making very little progress. (It’s worth noting that both Mama Cass and Keith Moon came to their respective tragic ends in Nilsson’s London flat.) Greg was unimpressed and getting increasingly fed up. He waited until the clock had ticked over past midnight on the Saturday, which triggered the top-whack penal rates for the crew, then kicked them both out.

Back in New Zealand, his thoughts turned to classic cars. He had always liked them and had owned an MGB and a Saab 96 in London, where car ownership was considered a bit eccentric. He realised there was no magazine for classics here and he couldn’t quite understand why people thought it wouldn’t work.

Greg said his previous bosses had often told him he was the best employee in the company, so he decided to back himself. Gathering material was a full-time effort. He wrote to all the car clubs and got some copy submitted, and he went to all the car events he could find. He also used to go through the paper looking for classic cars for sale and he’d approach the sellers suggesting they advertise to the specialist audience in his magazine. Everything had to be typed by hand back then. Greg’s brother, a truck driver, would drive around and photograph the cars.

“He did that for years, and for no money.”

Greg says those car classifieds were a staple of Classic Car for many years, right up until the internet took them away from both newspapers and magazines. But the new publication ruffled some feathers.

“I remember a guy from Auto Trader calling me up and having a go at me after the first issue went on sale. He wanted me to explain myself, as if he had marked out his territory.

“That was quite funny because I didn’t even know what Auto Trader was.”

Greg says he didn’t see any conflict at all, even if the concept of the free market had escaped his rival, as, “We were all classics, not Toyota Corollas”. That was then.

Crossing the Tasman

While advertising was the lifeblood of the magazine, Greg wasn’t that confident in selling it. He would sell just enough to cover his print costs and say, “Right, that’s it,” and get on with putting the next issue together.

Interestingly, as the magazine gained an audience and sales in New Zealand, Greg’s friend with the ‘how to’ advice on publishing suggested they start an Australian version together. The pupil was now teaching the master.

They started Australian Classic Car in 1993, and Greg says it was the start of an even crazier crazy time: “I was working seven days a week and late into the night putting out a magazine every two weeks.”

Eventually, he had to stop editing New Zealand Classic Car and asked assistant editor Allan Walton to take over.

The new international venture meant that Greg often had to fly to Australia. He recalled meeting one of his main advertisers at a car event. This jocular fellow kept loudly asking Greg if he had had any “fush and chups”. Greg was genuinely baffled.

“You know,” the advertiser persisted, “fush and chups!”

It meant nothing to Greg. He had spent 17 years in London, parsing every accent under the sun, so he wasn’t especially sensitive to the nuances of New Zuld and Strayan lingo.

Hawking his wares, a nice little BMW as a billboard

“I just couldn’t understand what he was saying. I felt like I was embarrassing him,” Greg says.

It was a sign of things to come. Greg says, while they eventually sold the Aussie version to Australia’s National Roads and Motorists’ Association (NRMA) the magazine never really took off over there. Australia didn’t have the heritage of British and European cars that we have here, which meant that the scene had a limited range. And the Aussies weren’t bothered about long-form stories. They just liked the pictures.

Back home, Greg says long-time contributor and key figure in the classic movement in Canterbury Trevor Stanley-Joblin was “terribly important” to the success of the magazine here.

“It meant we weren’t just a bunch of Jafas (Just Another Friendly Aucklander).”

Trevor recounts his early dealings with Greg elsewhere in this article.

Slow burn

Another landmark event that helped Classic Car become part of the public consciousness was the controversial introduction of unleaded fuel.

“A few cars burst into flames,” says Greg. “We thought all our classic cars were going to be buggered. We were terrified this was going to kill the whole scene.”

Greg now says they got the new fuel formula wrong at the start, which meant valve seals in older engines were giving up. The fires were caused by the fuel attacking older-style rubber seals in the carburettors.

A couple of writers on the magazine had been covering the issue in detail, but they were both overseas when the new fuel arrived, which meant that Greg was being interviewed by newspapers, television, and radio.

“A friend said he saw my picture in a newspaper in Thailand,” he recalls.

Greg living the dream

While that incendiary spotlight was memorable, Greg says that the magazine’s greatest legacy was more of a slow burn.

Someone told him back in the ’90s that they had overheard a conversation between a husband and wife surveying the splendour on display at a Canterbury classic car show.

The man said, “You know, this wouldn’t have happened a few years ago. This is because of Classic Car magazine.”

This made Greg feel there was a point to all the long days and nights for not a lot of financial return. He said that before the magazine started, if you wanted a new window winder or windscreen for an Alfa Romeo, you had to know where to go, or find someone who knew. The stories in the magazine detailed exactly where people carrying out restoration projects went for every last thing: for chrome, for headlights, for gearbox rebuilds.

“With the internet now, you can forget how hard it was to find the right people,” Greg muses. “The adverts were terribly important to the industry, because we started doing what they wanted, which was selling parts of classic cars, because now there was a way of connecting with people. And more people meant more suppliers and services. [The industry] here is still buoyant today because of that.”

Greg went on to found a number of other magazines and acquire others. Parkside today is a successful media company but Classic Car’s contribution to New Zealand’s cultural landscape remains special.

“It is still really having a big effect on a lot of people,” Greg says. “I’m proudest of that.”

This article originally appeared in New Zealand Classic Car issue No. 364